![]()

Chapter 1

William penn’s Witches

Margaret Mattson stood before William Penn, the Provincial Council and a jury of prominent citizens of the colony of Pennsylvania. It was February 1684, and Mattson and her neighbor Yethro Hendrickson were accused of practicing witchcraft. They were the first to be officially charged with such an offense in the young English colony, and the outcome of their trial would set a precedent for the prosecution of witchcraft in the future. Both of the women were of Swedish descent and from families who were remnants of the defunct colony of New Sweden that had predated Penn’s venture on the Delaware River. Mattson had pleaded “not guilty” to the charges against her at a prior arraignment, and Penn had assembled the council and a jury to hear the testimony of the women and their accusers. It seems that Hendrickson was not present at the trial as there is no official record of her speaking or giving testimony. An interpreter was present if needed, but it is not known how necessary he was or how much English Mattson could speak. It has been traditionally assumed that she spoke very little. The official record of the trial is sparse, so it has left many unanswered questions.

After convening the trial, several accusers were brought forth who testified that Mattson practiced the dark arts. A witness named Henry Drystreet claimed that he had been told twenty years before that Mattson was a witch and that she had bewitched the cattle of another farmer. Charles Ashcom asserted that Mattson’s own daughter believed her to be a witch and that Mattson had threatened her in spectral form, standing at the foot of her bed with a knife. The old woman had also allegedly bewitched her cattle. A woman named Annakey Coolin also believed that Mattson had used a spell on her cattle. Her husband had decided to boil the heart of a bewitched calf, presumably to draw out the witch. During the process, Mattson allegedly came to their door, disheveled and irate, demanding to know what they were doing. When they explained, she told them that they should have boiled the bones instead and muttered other “unseemly expressions.”

Mattson denied all of the accusations, of course. She insisted she was not present for the boiling of the calf’s heart and that she had no knowledge of the occurrence. She also questioned why her daughter was not present to testify if she believed her to be a witch. A common, but undocumented, legend about the trial tells that Penn himself questioned Mattson, asking if she ever rode through the air on a broomstick. Mattson allegedly did not understand the question and answered yes. Penn replied by asserting that there was no law against riding through the air on a broomstick.

When the testimony ceased, Penn met with the jury and gave them their charge concerning the case. Penn’s directions were not recorded but can probably be guessed from the verdict. The jury deliberated briefly and returned with its decision. The jury found Mattson guilty of “having the common fame of being a witch, but not guilty in the manner and form she stands indicted.” She was fined fifty pounds and released to the custody of her husband, Neels, to guarantee six months of good behavior. Despite being found innocent of witchcraft, Mattson has been known since as the Witch of Ridley Creek.

The unusual but wise verdict seems especially important in historical perspective, given that it occurred several years before the infamous Salem Witch Trials. While Penn and the jurors could not see into the future, they were certainly aware of the long history of witchcraft persecutions in Europe. To prevent such hysteria in the colony and to remain true to their pacifist Quaker beliefs, they could not set the precedent of convicting an accused witch, especially on such flimsy evidence. However, Penn and the jury were likely aware that the accusations against Mattson may have had more to do with personal vendettas than the black arts. Clearly, Mattson was not liked by many of her neighbors, and we will never know any more about her personality or interaction with others. Perhaps her neighbors were hostile to her because of her Swedish background or because they were jealous of her good land. To appease those who brought the charges against Mattson, the minor fine and “probation” would serve as a sufficient punishment and possible deterrent against future bad behavior without triggering more witchcraft accusations.

A postcard depicting the famous statue of William Penn that stands on top of city hall in Philadelphia. Penn’s careful handling of the colony’s first witch trial in 1684 prevented future prosecutions and the type of hysteria that would be seen in Salem several years later. Author’s collection.

Even though the colony and future state of Pennsylvania would not prosecute witches, it could not prevent its citizens from believing in them. The Quakers had little tolerance for the prosecution of witches and, at the same time, had little use for magic and the occult. As the prominent historian David Hackett Fischer pointed out in Albion’s Seed, the Quakers believed that evil in the world required no devil or magic but only the weakness and fallibility of men. However, as the colony grew and became successful, Pennsylvania’s Quakers soon found themselves outnumbered in their own land. As people of different religious and ethnic backgrounds arrived in Penn’s religiously liberated colony, they brought with them their own ideas about magic and witchcraft.

Evidence of the prevalence of such belief can be found throughout the 1700s in Philadelphia and its hinterlands. In 1701, a case of witch-related slander came to the city’s court. A butcher named John Richards and his wife were being sued by Mr. and Mrs. Robert Guard for slander. The Richards accused the Guards of bewitching another woman who allegedly had pins taken out of her breast. The case was eventually dismissed as “trifling.”

In Germantown, the practice of Pennsylvania German folk magic and folk healing was common. Well-known brauchers such as “Old Shrunk” Frailey offered their services to those who could pay, providing healing, removing curses and finding lost items and treasure. The practices of the German immigrants would spread and heavily influence witchcraft lore throughout the state. We will examine their beliefs more closely in the next section of the book.

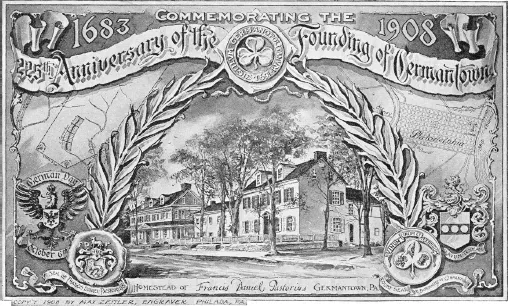

A postcard commemorating the founding of Germantown. Numerous German immigrants brought their traditions and culture to William Penn’s colony. Author’s collection.

By May 1718, there were apparently enough rumors and minor accusations of witchcraft that the legislature included an English law regarding witchcraft from the time of King James II when it made modifications to the colony’s legal system with the “Act for the Advancement of Justice.” The “Act Against Conjuration, Witchcraft, and Dealing with Evil and Wicked Spirits” had entered English law in 1685 and was added word for word to the new colonial act. Its presence was meant to serve more as a deterrent than anything else, and the law was rarely used or enforced. The addition of the law failed, however, to have any substantial impact on the personal beliefs of Pennsylvania’s residents. The very next year, an outbreak of witchcraft in Chester County led to the formation of a commission of judges from the county court specifically to deal with the occurrences. The commission was given authority to investigate all “witchcrafts, enchantments, sorcerers, and magic arts.” We do not have any record of the commission’s findings.

Further evidence of the continuing belief in witchcraft was uncovered during a 1976 archaeological excavation on Tinicum Island at Governor Printz State Park in Essington, not far from Philadelphia. Archaeologists discovered what is believed to be a “witch bottle,” probably buried in the 1740s, on what was then the property of the Taylor family. Witch bottles have been found frequently in England and have traditionally been used as a charm to protect against or reverse the curse of a witch and possibly identify the individual responsible. They were used by those familiar with folk magic and might be prescribed by the local cunning folk. This particular bottle had six straight pins inside. Often witch bottles contained ritualized items such as these to represent the victim’s pain or misfortune. They were mixed with urine or other bodily fluids of the victim and corked to trap the symptoms in the bottle and often reverse them on the witch. The witch might theoretically suffer until the bottle is uncorked. Similar techniques of sympathetic magic were used by the German immigrants as well. The presence of the bottle in Pennsylvania shows that at least some of the English settlers held onto the belief in witches.

Not everyone in early Pennsylvania took the belief in witchcraft quite so seriously. On October 22, 1730, Benjamin Franklin’s Pennsylvania Gazette published a report of a witch trial just across the Delaware River near Burlington, New Jersey, titled “Witch Trial at Mount Holly.” The article detailed the trial of a husband and wife accused of making sheep dance, hogs speak and generally causing terror among their neighbors. The accused witches agreed to be subject to two traditional tests to identify witches only if their accusers, another couple, agreed to submit to the same tests. They did, and over three hundred people from the town gathered to watch with anticipation. For the first test, each of the individuals had to step on a scale with the Bible on the other side. It was believed that a real witch would be lighter than the Bible. All four took their turn, and all outweighed the Good Book. The second test involved being tied up and thrown into water. If the person sank, they were not a witch, but if they floated, they were using supernatural forces to protect them. This time only the male accuser sank, and the other three remained floating on the water. The female accuser reportedly claimed that the witches were making her float, but some observers questioned whether the women’s undergarments were trapping air and helping to keep them up. It was decided to pull them all from the water and wait until warmer weather, when they could be cast into the water naked. Though the story of the Mt. Holly trial spread quickly and was even reprinted in Britain, it turned out to be a hoax. It is now believed by many that it was Franklin himself who wrote the story to poke fun at superstition, and it seems to match the style of his satire.

Though the Gazette’s story was a hoax, it certainly seemed to be believable enough for many of its readers. The city of Philadelphia saw other occasional, and very real, incidents involving accused witches as the century progresses. After refusing to prosecute an accused witch in 1749, authorities were forced to deal with a riot when angry citizens formed a mob to protest their inaction. In 1787, a tragic event occurred in the city’s streets. A mob harassed and attacked an old woman who was believed to be a witch. She had been attacked on two previous occasions but had survived. This time the mob was relentless, shouting accusations and berating anyone who attempted to come to her aid. They began throwing stones, and the woman was killed in broad daylight.

Still, as the century progressed, the public presence of witchcraft in Philadelphia gradually declined. In 1754, Franklin tried to have the Witchcraft Act repealed by the colonial legislature, but his efforts were defeated. The act only disappeared in 1794 when the state was restructuring its legal system as part of the young United States. Witchcraft, in both belief and practice, was present behind closed doors, but it had become a subject of mockery for the urban elite and educated. The belief in witches still thrived in Pennsylvania, however, and is surprisingly well documented in Pennsylvania Dutch Country and in counties farther to the west. It is the folk traditions of the state’s German population that dominate Pennsylvania’s witchcraft traditions.

![]()

Chapter 2

Powwow and Hex

The Pennsylvania German Tradition

The most extensive and well-documented system of folk magic and healing in Pennsylvania is that belonging to the Pennsylvania German (or Dutch, as they are often called) immigrants and their descendants. It is also the system most associated with witchcraft as a result. Multitudes of German immigrants made the journey to Penn’s Colony to take advantage of the economic opportunity and religious freedom that they could not find in Europe. At first they settled in large ethnic communities such as Germantown, but soon spread across the growing colony/state to take advantage of the fertile farmland and resources. The German settlement was particularly dense in the counties in the southeastern corner of the state around Philadelphia. The area eventually became known as Pennsylvania Dutch Country to legions of twentieth-century tourists. Though they became Americanized in many ways, the Germans held strongly to elements of their culture and blended New and Old World customs to form a distinct identity. Even their language became a unique Pennsylvania German dialect.

Though there were a great variety of religious denominations among these settlers, there was a common tradition of folk magic that was practiced across denominational lines, with the exception of the “Plain Dutch,” such as the Amish, who rejected the practice. For large numbers of these Germans, the belief in folk magic was integrated with their Christian beliefs, as occult ideas were generally more acceptable in Germany than in England. At one end of the magical spectrum was the practice of Brauche or Braucherei, more commonly known as powwowing (not to be confused with the Native American ceremonial practice of the same name.) Powwowers performed magical-religious folk healing and drew healing power from God. Braucherei is usually translated as “trying,” or sometimes “using.” At the other end of the spectrum was Hexerei or witchcraft. Practitioners of this form of black magic drew their power from the Devil or other ungodly sources. Since the perceived supernatural battle between good and evil was not going to be played out in Pennsylvania courts, the bewitched had to turn elsewhere for assistance. Powwowers and hex doctors filled the void for believers, and the culture of folk magic continued to flourish.

POWWOWERS, HEX DOCTORS AND WITCHES

Powwowers, and their equivalents in other ethnic groups and cultures, played an important role in the years before scientific medicine came into maturity. They offered relief from ailments and, more importantly, a degree of hope. The use of folk magic could provide a sense of control in a world that is often beyond control. Even after the professionalization of medicine, powwowers provided an explanation and a way to push back against misunderstood and unknown forces in the world. David Kriebel, in his masterful study Powwowing Among the Pennsylvania Dutch, succinctly identified the functions and services provided by powwowers. Generally, powwowers provided cures and relief from symptoms of illness, protection from evil and the removal of hexes and curses. They also located lost objects, animals and people; foretold the future; bound animals and people (such as rabid dogs and thieves); and provided good luck charms. To carry out these functions, powwowers used charms, amulets, incantations, prayers and ritualized objects. It was generally believed that anyone could powwow, but members of certain families were especially adept. These families passed the traditions down from generation to generation. Transmission of the practice usually alternated between sexes, unless there was not an heir of the opposite sex.

The opposite of the powwower was the witch, who utilized dark magic that was beyond the normal use of a folk healer. The witch harassed neighbors and committed criminal acts with supernatural power that was not of God. Sometimes these witches were called hex doctors. The term “hex doctor” can be confusing, however, because it can imply multiple things. Sometimes the term was applied to powwowers who were also knowledgeable in the ways of Hexerei and were skilled at battling witches and removing curses. These hex doctors fell into a gray area between witch and powwower. Sometimes they would cast hexes for a price or out of revenge. It was not uncommon for someone to seek out one hex doctor to remove the curse of another. For many Pennsylvania Germans, and certainly for outsiders, the lines between powwower and witch were not as sharply drawn into our convenient categories. There are many who would label any use of folk magic as witchcraft, no matter the intention.

Since no one ever readily identified herself (or himself) as a witch, it is not always clear how one would learn the art of Hexerei. It was generally assumed, that even if the witch was not making a direct pact with the Devil, the witch was drawing her power from diabolical forces as a teufelsdeiner, or devil’s servant. Richard Shaner identified several methods by which one could become a witch in the Pennsylvania German tradition. One particularly cruel method required the person wishing to become a witch to boil a black cat or a toad alive. The would-be witch would have to gather the unfortunate animal’s bones and toss them into a stream or creek. One bone would supposedly float against the current. The bone would then serve as the witch’s source of power. Another method involved the person drawing a circle on the ground made out of coal. She would then step into the circle while holding out her hand. The Devil would supposedly appear, taking her hand and marking it. From that point on, the person would have the power of a witch. A third possible way required the person to ...