![]()

CHAPTER ONE

American Ways of Death

REVEALED:

Death’s brave new life

Jon Austin had been working as founding curator at the Museum of Funeral Customs for about a year when he had a curious visitor. His office door is always open to the lobby, so he could observe her as she neared the exit. “Thanks for visiting!” he called.

She was an elderly woman, probably in her late seventies or early eighties, and she nodded in his direction as she passed the antique carriage hearse on her way out. But then she stopped and stood completely still for a moment before turning around and returning to his office doorway.

“You didn’t tell all of the story,” she said.

When recounting this, Jon Austin re-creates his own confused expression: He wanted to be polite, but at the same time, he had worked hard for months to get the museum’s collection of American death memorabilia just right, and so, “there’s kind of this bravado in me,” he says. He asked her, “What exactly have we failed to include?”

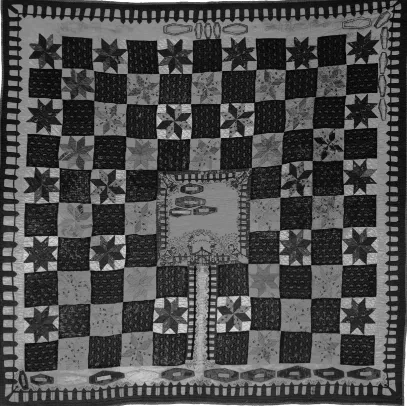

Graveyard quilt, Nina Mitchell Collection, 1959.13, 1843.

COURTESY OF THE KENTUCKY HISTORICAL SOCIETY.

She paused and then said, “You haven’t explained what they do with the rest of the body.”

And Jon Austin thought Rest … ? But what he said was, “I’m sorry. But I can’t understand your question. Can you help me? Give me more information?”

She repeated it. “You haven’t explained what they do with the rest of the body.”

After one more confused exchange, she told him what she meant. When she was a child, a grown-up had told her that what you see in the casket is all that’s present. “That’s why they only open the upper end of the casket. Because that’s all that’s there.” And now, this octogenarian asked, “What do they do with the rest of the body?”

Jon Austin’s chief joy in life sprang from putting together picture-perfect exhibits like those here: the 1930s embalming room display with its gleaming metal table, the early twentieth-century home-funeral display with its chrome-plated art deco casket jacks and dark velvet curtains. These opportunities to delve into and re-create history had driven him to pursue a career as a museum director and curator. He had not anticipated ever being faced with counseling a stranger about her personal experiences with funerals and death.

He stumbled and stammered out an explanation, offering to put her in contact with a number of funeral directors, friends of his who would support his assertion that human bodies are not cut in half before being buried.

She nodded and thanked him but refused his offer. Then there was a long pause, and he didn’t know what to do. “I mean, human emotion says, ‘Okay. This woman needs comfort.’ But how do you offer that to a total stranger in an environment like this?” In the end, he offered her some water. After she left, he collapsed into his office chair and couldn’t concentrate for the rest of the day.

In his job, Jon Austin fields plenty of basic questions about the practices standard to the funeral world. Embalming. How is it done? What chemicals are used? How long does it take? How effective is it? It makes sense. No one knows about the details of embalming except embalmers. The day the elderly woman came in, however, was the first time he had to offer someone intimate guidance about her own life experiences. It wouldn’t be the last. He had known this on some level from the beginning but relearns it every day: To Americans, death is an enigma.

Take the cooling board. Before my own visit to the Museum of Funeral Customs, I had heard bluesmen like Blind Willie McTell sing about cooling boards in songs like “Death Letter” and “Cooling Board Blues,” but I had never seen one myself and had never attached an image to the words. Here’s one: Imagine an ironing board without legs. The wooden surface of the cooling board is perforated with holes; these might be evenly spaced or might cleverly spell out the name of the manufacturer. Many were covered with cane latticework instead of solid wood. Ice was placed beneath to slow decomposition, hence the name: cooling board. When embalming came onto the scene, blood and other fluids not sucked up by embalming tubes could drain through the holes or lattice into the tray beneath.

One hundred to one hundred fifty years ago, the cooling board was the central, commonplace object involved in preparing dead bodies for funerals, a piece of furniture that predated the metal embalming tables that star in so many of today’s crime investigation shows. Basically a portable platform on which to lay out dead bodies, the cooling board was a familiar if less-than-pleasant essential to everyone who lived and breathed in the decades before the advent of funeral homes. The family or undertaker used it to prepare the body, and it could also stand in for viewings when the casket did not arrive from the local carpenter or big-city manufacturer in time.

And yet a 2008 Internet image search on the term turned up nothing.

Not a single photograph of a cooling board emerged on five pages of Google. On Wikipedia, that everyman’s fount of collective knowledge, the given definition left a lot to be desired. No dates—just a garbled statement about wrapping a body in a shroud in the winter and storing it in a barn until the ground thawed, and an acknowledgment of the term’s popularity in a number of old blues songs. “This entry is an orphan,” read a disclaimer at the top of the page. A few years later, in 2012, I did another search; this one turned up a bit more, most of it photographs. On one site, an anonymous young girl lies on her cooling board; another site features Lizzie Borden’s bloodied father on his. Graphic representations far outnumber real explanatory records, though. That poor Wikipedia entry is still orphaned.

This once workaday piece of furniture has become obscure and unknown, living on only in the minds of those in funeral service and in the music of Son House. A vital rite reduced to a tinny old song on late-night radio. The tune is familiar to our bones, but heck if we can recall the words.

I didn’t just wake up one morning and decide on a whim to start finding out all I could about cooling boards, cremation, and Victorian mourning jewelry made from human hair. My curiosity in these things developed because I’d been collecting stories from contemporary people involved with memorializing the dead—those who proffered various memorial choices, and those forced to make them. I was curious about the personal life story of the contemporary memorial photographer, the small-town funeral director, and the woman who had spent years tending a roadside memorial she’d created for her daughter.

But commonalities kept popping up. It turns out that the friends who remember their dead biker buddy by getting his image inked into their arms give extremely similar rationales for their choice as the family who has its patriarch embalmed, funeralized, and buried in what has become (only in the past hundred years, mind you) this country’s traditional style. Purveyors of all-natural “green” burial give heartfelt arguments for what they do that sound extremely similar in some ways to a group they’re often pitted against: traditional funeral directors. Meanwhile, today’s explosion of options for jewelry that contains funeral ashes has a lot in common with mourning jewelry worn by Victorians.

Every time I spoke with someone about why she or he chose burial in a historic cemetery, ash scattering in the Passaic River, memorializing with a postmortem photograph, or immortalizing through ink on skin that would last forever—or at least till the bearer was gone—I heard echoes of some other answer given by someone who lived on the other side of the country or the other side of the century.

And every seemingly quirky path eventually wound its way back to the here and now—which made it all feel far less quirky. This journey, for me, was a visit to the Museum of Funeral Customs writ large. You go because it seems odd and fascinating. Sometimes it’s ha-ha funny, á la the hilarity that ensues when the preacher, the priest, and the rabbi meet St. Peter at the pearly gates. What I found, though, is that on the heels of every eccentric moment emerged some poignancy: The outlandish advertising claims made of early embalming fluids (“You can make mummies with it!”) and the staggering multitude of Civil War deaths that galvanized this uniquely American competition. The talk that springs up at a green-burial cemetery among a group of ordinarily taciturn men as they work to dig their brother’s grave. The memorial weenie roast the family holds in his honor every year thereafter. And something always sprung up to remind me that this strange land of mourning, of memorialization, and of death itself is one for which we’re all eventually bound.

Two and a half million Americans died last year. That makes 2.5 million human stories about the final decisions made for a beloved grandfather, a coworker’s sister, or that guy who played guitar for spare change outside the coffee shop. I began this journey fascinated by vaults that curb decomposition for decades, urns shaped like Great Danes, and rocket-ship victory laps for cremated ashes. By the time I finished, I was wondering what these choices said about us, and about the entire American landscape of mourning.

WHAT YOU HOLD in your hands presumes to be no exhaustive history of funeral practices in America. It’s a scattershot thing, this history. Like each of our stories when we lose a family member or a close friend—and this is every single one of us, sooner or later—the facts of death’s history and current experience in America are strewn haphazardly across our nation’s wide landscape, disorganized and largely unheard. You can find it in the memories and stories of families who work in funeral service—although many of them are reluctant to talk with outsiders, threatened as they are by drastic threats to their livelihood in the changing ways we do death. You can find it in the ancient, curling pages of nineteenth-century funeral-trade publications with names like The Casket and Sunnyside. Death’s Present and Past are here and they’re real, but they remain, to most of us, an unseen layer in the atmosphere of our day-to-day lives. A mystery. To most of us, what we actually know of death is only our own reaction when it touches us.

Nor does this book speculate on or predict future patterns of American memorialization. I’ll leave that to the scholarly types. I’m much more interested in learning what it’s like to bury your family pet at sea or to conduct five funeral services in one week or to write an obituary for a stranger. What drove Victorian women to wear black veils and scratchy black mourning crape for a full year? What was that like? Are there present-day American equivalents? Most of all, what of these personal stories? What made Elizabeth Stuckman choose burial in a nature preserve for her brother? Why did B. J. Dargo create an artificial coral reef from her son’s ashes? Why does Mary Wilsey still maintain that roadside memorial at the spot where her daughter’s car crashed?

These stories about mourning’s interior worlds build something bigger. Together their echoes resound, a small note in one place playing up another elsewhere on the map or elsewhere in time. We catch glimpses of something bigger—the biggest “something bigger” we can conceive of. A death landscape that’s as deep as it is wide—more-over, the landscape of our lives themselves.

![]()

CHAPTER TWO

Gone, but Not Forgotten

REVEALED:

How America went from mourning veils to veiled mourning

Let’s start in Illinois.

Despite the extravagant unwholesomeness of its contents—the glossy embalming trocars and the jet black horse-and-buggy hearse—the Museum of Funeral Customs is, in outward appearance, wholly unassuming. One approaches more than half expecting outright kitsch. One is primed for it, in fact, by the presence, one block away, of a tourist trap shaped like a log cabin. We are, after all, in Spring-field, Illinois, where it seems every other downtown building is somehow Lincoln-themed or -decorated. The log cabin across the street from the museum hawks purple plastic Lincoln backscratchers, be-feathered and beglittered dream catchers of varying size and hideosity, and pennies embossed with the twinned faces of Honest Abe and John F. Kennedy sold with one of those lists enumerating twenty-two strange coincidences between their deaths.

Within sight and walking distance, the Museum of Funeral Customs seems to shrink almost visibly away from the Lincoln Log Mart (name changed because the real one is much more boring). While the latter marches right up to the road sporting a large, hanging sign announcing itself, the museum retreats behind a small square of tasteful lawn, its light pink imitation sandstone causing it to resemble a modern funeral home.

Locket with chain of braided hair, between 1861 and 1865.

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS, PRINTS & PHOTOGRAPHS DIVISION, LILJENQUIST FAMILY COLLECTION OF CIVIL WAR PHOTOGRAPHS, LC-DIG-PPMSCA-37494.

When I ask Jon Austin about the neighboring tourist shop, his polite facial expression takes on a strain, like a canvas stretched a hair too tight. “Yes,” he allows, “they have some … interesting items for sale there.” The curator of the museum is polite but firmly distancing. There’s an impulse to make absurdity of his establishment too, to make death ludicrous; it’s an impulse he politely denies.

Once the director of the Illinois State Historical Society, Jon has curated and directed the Museum of Funeral Customs since helping the Illinois Funeral Directors Association shape the place’s design and goals eight years ago. A physically slight and conversationally intense man, he enjoys discussing the very kookiest details of American funereal history without ever quite losing the gravitas common to both funeral directors, with whom he spends a good deal of his time, and professional historians, which he is. You get the feeling he’d never use the word “kooky.”

It turns out I wasn’t imagining it: Jon tells me the museum’s facade is indeed designed to resemble that of a modern funeral home, its salmon-colored stucco inlaid with filled-in arched window shapes just like the chapel it never was—although it sits across the street from a real funeral home and catty-corner to the hilly, manicured 365 acres of Oak Ridge Cemetery. Oak Ridge is both the final resting place of Abe Lincoln and a working cemetery with hundreds of active and available plots.

The museum is small. It takes most people about forty-five minutes to walk through its display room, Jon tells me after I finish my own walk through the place. It takes me three hours.

I can’t help it. Just for starters, there are burial boxes galore here, including a small, gabled, wooden coffin that I see and immediately think, “Tiny Dracula.” Tiny Dracula widens at the shoulders and comes to a point at the head, just like vampire coffins in old movies. It is meant for no monster, of course, but a nineteenth-century child. Perpendicular to its foreboding angles sits a fluffy, pink twentieth-century counterpart. A nearby sign explains that in the United States, the term “coffin” technically refers to the older, diamond-shaped container.

The term “casket” is an American death invention from the late 1800s. It comes from a French word meaning “a box containing precious valuables.” The human body as a valuable jewel. In Great Britain today, they still use the straightforward “coffin,” while here in the States, where we’ve continued to develop and elaborate on our funeral customs far beyond anything our European cousins have done, our burial boxes are no exception. The prettier “casket” prevails.

There’s a respectable amount of floor space here devoted to the era that invented the casket. The display on nineteenth-century America, however, is decidedly not pretty. Here on view are the lives and death practices of the same people who built the most grandiose cemeteries the Western world ever saw—places like Oakland Cemetery in Atlanta and Mount Auburn outside Boston. There’s something about this part of the museum that makes the hairs on my neck and arms stand straight up. It’s so morbid. Like many an account of the Victorian era itself, it’s also claustrophobic. I’m surrounded by long black dresses and jackets standing rigid and silent like empty husks. It’s all Addams Family and photos of prairie women and their families sitting stiff, still, unsmiling.

(“Victorian era” technically refers to the years 1837–1901 in Great Britain—the years when Queen Victoria reigned. Of course, the States had its own complex patchwork of historic eras during the same period. When I say “Victorian,” I’m actually referring to the larger sense of the word, which encompasses domestic practices and style in the Western world during the same period.)

The Ghost of Funerals Past feels exceptionally potent in this part of the museum, and not just because of these objects’ origins in Dickensian days. These items are strange in all their heavy-handed austerity, but they’re also familiar. The drab clothing, hearses, and funeral processions that reached their apogee in the late 1800s pretty much cast the die for our current death traditions. Even if your own choices—say, to wear bright colors and scatter so...