1

The origins of the dear green place

The peopling of the land now occupied by the city of Glasgow commenced sometime during the centuries following the last ice age when groups of itinerant hunters and gatherers moved into the area in search of a livelihood. The origins of the present city, however, lie much later – in the sixth century AD, when settled peoples began to exploit the natural resources of the area. The available evidence suggests that the earliest settlement on the site consisted of a bi-nuclear village, with a fishing community by the river overlooked by an eccesiastical foundation on the hilltop above. Until this period people had existed in a largely dependent relationship with their environment. Over the succeeding centuries, aided by a series of technological innovations, the early Glaswegians were able to exert increasing control over the physical environment. Most significantly, through the efforts of successive generations, the Clyde was transformed from a limpid stream into a world port and shipbuilding centre. Nature is a hard taskmaster, however, and command of the river is achieved only at the cost of eternal effort and vigilance. Cessation of dredging could see the river revert to its natural shallow, and in places fordable, state.

In view of the primary importance of the relationship between human occupance and the natural environment, it is appropriate to begin our discussion by considering the nature of the city’s physical setting, before we turn to examine the origins of the early settlement of Glasgow.

The Physical Environment

The history of Glasgow provides an intriguing example of the influence of geological and geographical conditions on the development of a city. Glasgow occupies a strategic riverine location at the western end of the down-faulted Midland Valley, an important through-route linking the east and west coasts of central Scotland. The significance of this geographical location for the city’s subsequent development is matched, in equal measure, by the value of its geological inheritance. The land on which the present city stands was formed in the course of the last 500 million years by successive periods of sedimentation and volcanism, separated by episodes of crustal movement and mountain building.

Of particular importance for the subsequent human geography of the area was the formation of the Carboniferous rock series some 250–200 million years ago. These primarily fossiliferous rocks were formed by the entry into the rift valley of sediments of marine, estuarine or lagoon origin which contained the economically valuable coal seams and ironstones upon which the growth and prosperity of industrial Clydeside was based. Such gifts of nature, however, only become resources when their potential is recognised by people armed with the technology to exploit it, and so the coal measures lay undisturbed for hundreds of millions of years until the first stirrings of industrialisation in the region in the eighteenth century. The Limestone Coal Group of the Carboniferous Limestone Series which contained the rich seams of coal and ironstone attained maximum thickness in the Kilsyth area to the east. Within the city itself the coals of this group fell into two subdivisions named after the Garscadden and Possil mining fields. The latter contained several varieties of good coal and blackband ironstones and was worked extensively in the western districts of the city underneath Partick, Kelvinside and Hillhead. An unfortunate modern-day consequence of this activity is the presence of abandoned workings, which have led to subsidence and damage to buildings in the area. Other natural assets laid down in the local geological store included the limestones later freely worked at many locations in the Robroyston, Garnkirk, Darnley and Bedlay districts for use as building cement, agricultural lime and as a flux in iron smelting. The Millstone Grit measures of the Carboniferous Series also yielded sandstones of refractory character suitable for the bottom of furnaces in steelworks and forges (fireclay) and, when ground down, a sand suitable for moulding castings (green sand). The formation of the Carboniferous sediments was interrupted by volcanic activity, which was especially powerful during Lower Carboniferous times when the Clyde lavas were exuded. As well as forming city landmarks such as the “crag and tail” of Necropolis Hill, the resulting dolerite sills were quarried at places such as Cranhill, Shettleston and Provanmill within the city to provide setts and road metal for the expanding metropolis.

The natural resource most visible in the city today is, of course, the stone used in its construction. The chief local building stone is the sandstone found immediately above the Upper Limestone Group and known locally as Barrhead Grit (south of the river) or Bishopbriggs Sandstone after the major quarry at Huntershill in Bishopbriggs (Clough and MacGregor 1925). While the thickness of the beds ranges from a few centimetres to, exceptionally, twenty metres, most are between one and five metres. As the architecture of the modern city shows, sandstone is characterised by a variation in colour reflecting the climatic conditions at the time of its formation. Some of the best quality sandstone with good weathering properties is the creamy white “liver” freestone (that is, stone in which no bedding is apparent and which can be worked with equal ease in all directions). This type occurs just above the base of the Upper Limestone Group. The Huntershill (Bishopbriggs) and Garscube (Anniesland) quarries were sited to take advantage of this horizon. Slightly higher in the geological sequence is the Giffnock stone, also used widely in the production of the built environment. Indeed, so extensive was the extraction of stone from the Giffnock quarries of Braidbar and New Braidbar that it almost completely undermined the intervening hill, and broad pillars of sandstone had to be left to support the gallery roofs. These quarries were worked until the turn of the century. Similar though less extensive mining also took place at Huntershill until a serious roof fall in 1908 led to closure of the workings. Towards the end of the Carboniferous period, as the climate became drier the sand grains being deposited were coated with red iron oxides, producing a distinctive pink or red coloured building stone. As we shall see later, until circa 1890 most of Glasgow’s building store derived from the Carboniferous measures, but as the local quarries were exhausted the distinctive New Red Sandstone (seen, for example, in the Kelvingrove Art Gallery and Museum) was imported from Ayrshire and Dumfriesshire.

Whereas the solid geology underlying the city was created over the past 500 million years, the visible landscape is the product of more recent geomorphologic processes. In the course of the last major glacial epoch, around 10 000 years ago, the erosional power and, in particular, the depositional activity of the ice overlaid the underlying bedrock with drift materials and moulded a landscape that the modern observer would find not unfamiliar. The most prominent relicts of the glacial era are the pearshaped hills or drumlins formed of till deposited and sculpted by the advancing glacier. More than 150 drumlins can be identified within the boundaries of the city. These range in height from under 10 metres to a large number over 25 metres, and have their long axes paralleling the direction of ice flow, roughly from north-west to south-east (Figure 1.1). The impact of these landforms on the appearance of the city is testified by district names such as Ruchill, Garnethill, Govanhill, Hillhead and Mount Florida, and by road deflections such as the alignment of Crow Road between Dumbarton Road and Anniesland Cross. In places where two drumlins are linked by a ridge road engineers have taken advantage of the topography as, for example, in the case of University Avenue, which passes between the drumlins of Gilmorehill and Hillhead, or Sauchiehall Street, which runs between the drumlins of Garnethill and Blythswood (Elder 1936). While in some areas of the city, such as Dowanhill, Park Circus and Mosspark, streets follow the contour pattern in deference to the drumlins, in the grid developments of the central city a formal chequerboard street pattern has been imposed on the hilly terrain with little regard to gradient in an emphatic statement that reflects the self-confidence of Victorian urbanism.

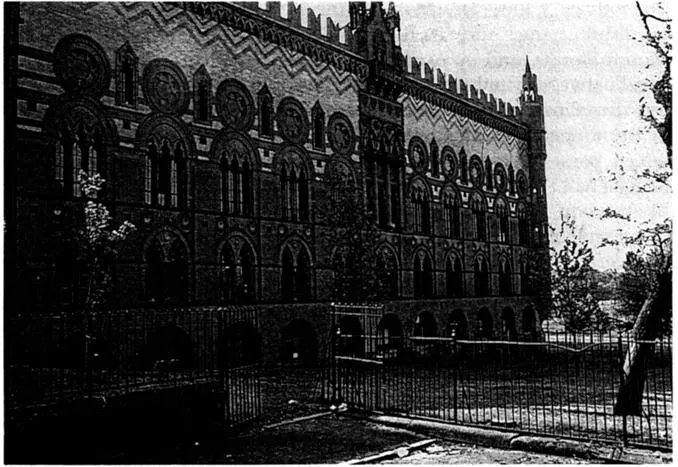

As well as its landscape legacy, the glacial period also provided its own raw materials for the benefit of future citizens. A large area of the city on the north side of the river is covered by the brick clays of the post-glacial terraces. Indeed, the extent of these clays poses the question of why brick buildings are not more common in Glasgow. Much of the (boulder) clay, however, contained pebbles, and only where the sea had winnowed the clay from the stones were useful brick clays found. Early brick-making was on a small scale mainly located adjacent to the building works. Later the blue/brown clays were exploited more widely during the nineteenth-century expansion of the city, particularly in the brickfields of Kelvinside and the western suburbs as well as at Robroyston in the north of the city, Parkhead in the east and Polmadie on the south side. Bricks were commonly used for internal walls, gables and stair towers (where they could more easily be formed into a curve) but were only rarely used for the visible parts of buildings. In general, brick was more often used for industrial buildings such as cotton mills and the famous Templeton carpet factory in Calton, which was constructed in 1888 as a replica of the Doge’s palace in Venice (Figure 1.2). Compositional bricks were also made from Carboniferous shale that had been extracted during coal mining operations and dumped in spoil heaps (bings). Glacial boulder clay at Hamiltonhill was quarried to provide puddling material for the nearby canal, and in the area between Tollcross and Broomhouse sand and gravel mounds deposited by the retreating ice front were excavated for building use.

During late-glacial and post-glacial times there was isostatic and eustatic recovery of the land from the burden of ice. Evidence of this in the Glasgow area is seen in the occurrence of raised beaches at heights of up to 100 feet. Within the city Dumbarton Road makes good use of the level shelf of an old raised beach. The 100-foot raised beach is marked by deposits of finely laminated clays, within which arctic forms of molluscs have been found. These remains provide a good indication of the climate at a time when an arctic sea occupied the estuary of the Clyde. Conditions on land would have been akin to the Siberian tundra, and there is archaeological evidence of mammoths and woolly rhinoceroses roaming the area. The first groups of people who made their way into the area around 8000 years ago were hunters and gatherers interested in taking advantage of the abundant natural resources, in particular the fauna and flora, of the river basin.

Early settlement and settlers

As we have seen, the particular physical advantages of the local geography influenced the locational decisions of the earliest settlers, and this, in turn, laid the foundations for the modern city of Glasgow. A basic question to be addressed, therefore, is – why here? What attracted early peoples to settle in this particular place at latitude 55°51 'N, longitude 4°17' W – a location that over succeeding centuries developed into one of the most northerly of the great cities of the world?

Most of the natural mineral resources we have identified lay beyond the reach of Stone Age man. Other natural conditions were of more immediate attraction. Not the least of these was the River Clyde, which, as well as being fordable, offered a source of fish and salt. The site also gave ready access to the surrounding countryside, which provided primitive hunters with food and fibre. The valleys between the wooded drumlins afforded shelter and a source of water from perennial streams such as the Molendinar. The local soils provided pottery clay and the forests an abundant supply of firewood and the raw material to fashion dugout canoes. To date, almost 20 of these ancient craft have been found at sites on both sides of the Clyde. Their occurrence as far from the present river as Drygate and as much as 22 feet above the present high water level shows that the site of Glasgow up to the 25 foot contour was then occupied by water. At that time the Clyde estuary covered the present Argyle Street and Trongate on the northern bank and Govan and Polmadie on the southern bank (Gregory 1921). Evidence from kitchen middens and other artefacts tends to confirm the significance of the 25 foot “Neolithic” raised beach in the settlement history of the site. Somewhat incongruously, a Neolithic axe was unearthed at the corner of Sauchiehall Street and Buchanan Street in 1848. Another was found in 1854 in the Clyde at Rutherglen Bridge, while a third was uncovered in Kingston Dock in 1866. The fact that not all of the raw material for the tools was of local origin confirms the existence of long-distance trade even in the fifth millennium BC. Axes of North Welsh and Antrim stone are not uncommon, while a polished stone axe head found inside a dugout canoe in 1780 at Old St Enoch Church was made of a jadeite known to occur in the Alps.

In the absence of documentary evidence, the population history of the area from the Neolithic until Roman times is uncertain. What is clear is that the embryonic Glasgow’s position as a route focus exposed the original inhabitants to a range of influences. Most significant of these were the Iberian peoples who migrated up the Clyde estuary from the west and south, and the Bronze Age Beaker Folk who came from the south and east. Evidence of Bronze Age settlement in the form of stone cists or coffins accompanied by food vessel pottery was discovered in 1928 in a sand pit at Greenoakhill, Mount Vernon, and elsewhere including Springhill Farm, Baillieston (1936), Springfield Quay (1877) and Garngad quarry (1899). Another indication of human settlement activity in the area in the second millennium BC is a boulder decorated with distinctive cup and ring markings found in Bluebell Wood, Langside. The shores of the Clyde below Glasgow and the lochans to the east of the present city were foci for settlement in the later first millennium BC and the early first millennium AD, Crannogs - timber and stone houses built on artificial islands – existed in Bishop Loch and Lochend Loch. Finds from the former site include a socketed iron axe head. By around 500 BC it is reasonable to assume that the local population had mastered the technology of the Iron Age. Excavations at Shiels, Govan in 1973–1974 uncovered an Iron Age ditched enclosure measuring 42 m x 36 m with a single entrance to the east and a rectangular timber building of 5 m x 3 m. Other earthworks at Camphill in Queen’s Park (excavated in 1867) and at Pollok Park (excavated in 1951) confirm Iron Age occupation of the sites (with the former site reoccupied by an earth and timber ringwork castle in mediaeval times). Since the “haugh” lands bordering the river Clyde were marshy and prone to flooding it is most likely that the Celtic settlement at Glasgow was established on a drier site, near the Molendinar burn. Although a definitive statement is impossible, it is probable that the origins of the name of the modern city derive from this period. While some historians suggest an origin in the Gaelic words meaning “dark glen”, alluding to the ravine through which the Molendinar flowed, it is equally probable that the modern name of the city derives from the Celtic language as Glasghu meaning “green field” or “dear green place”.

By Roman times the lands around Glasgow were inhabited by people of the tribe of Damnonii, whose territories extended from the shores of the Firth of Clyde south of Irvine through western Scotland to the western parts of Tayside. It would appear that, unlike the Selgovae, whose territory was tightly regulated and controlled by the Roman administration, the Damnonii maintained a degree of control over their own affairs as a form of “treaty state”. Evidence of a Roman settlement on the site of Glasgow is tantalisingly faint. In AD 80, according to the historian Tacitus, Julius Agricola, governor of Britain, resolved to secure the territorial gains made in previous advances by establishing a chain of garrison forts between the waters of the Clyde and Forth. Until recently it was considered likely that these forts were hidden beneath the Antonine Wall, built across the isthmus 60 years later, but the discovery of a late first century fortlet at Mollins 6 km south of the wall, suggests that the two defensive lines may not have been wholly conterminous. Given the probable spacing of the Agricolan garrisons of 10–13 km it is likely that one of the forts lay within the present boundaries of Glasgow. However, apart from a few finds on Glasgow Green overlooking the confluence of the Molendinar and the River Clyde, little Roman material has been found. Archaeological evidence suggests the presence of a fort at Balmuildy and a fortlet about one Roman mile to the north-west at Summerston but the latter site has been damaged by subsequent quarrying, possibly by the Laird of Dougalstoun in the 1690s, when he removed the foundation of the Antonine Wall to provide stone for his park dyke (Ritchie et al. 1990). During the half century of occupation of the Antonine Wall the Romans, with a port near Bowling, probably saw no need to erect a permanent settlement at Glasgow. Nevertheless, the Pax Romana would have been of considerable benefit to the native communities of the lower Clyde. When the legions finally departed the area circa AD 163 the effect on the local economy and administration must have been catastrophic.

On the withdrawal of the Romans from southern Scotland the ensuing political vacuum was filled by the Britons, who moved north from Cumbria. The capital of the British kingdom of Strathclyde was at Dum...