- 320 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

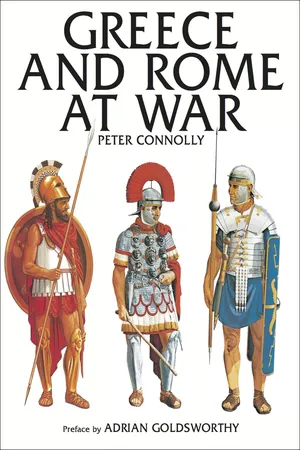

Greece and Rome at War

About this book

The renowned archeologist's classic guide to twelve centuries of ancient military development, beautifully presented in colorful illustrations and diagrams.

Generations of archeologists have been inspired by Peter Connolly's beautifully rendered, highly detailed illustrations of ancient arms and armies. This comprehensive volume offers a bird's eye view of not only battles, but the weapons, shields, and armor used centuries ago by Greek and Roman warriors. With extensive text describing each piece, this collection offers an ideal introduction to the subject of warfare in the ancient world spanning from 800 BC to 450 AD.

Incorporating new archaeological research and the contributions of other scholars in the field, this new edition of Greece and Rome at War provides detailed explanations of the classical armies' manufacture and use of their armaments. These full-color illustrations, maps, diagrams, and photographs bring the past to vivid life.

Includes a preface by Adrian Goldsworthy.

Generations of archeologists have been inspired by Peter Connolly's beautifully rendered, highly detailed illustrations of ancient arms and armies. This comprehensive volume offers a bird's eye view of not only battles, but the weapons, shields, and armor used centuries ago by Greek and Roman warriors. With extensive text describing each piece, this collection offers an ideal introduction to the subject of warfare in the ancient world spanning from 800 BC to 450 AD.

Incorporating new archaeological research and the contributions of other scholars in the field, this new edition of Greece and Rome at War provides detailed explanations of the classical armies' manufacture and use of their armaments. These full-color illustrations, maps, diagrams, and photographs bring the past to vivid life.

Includes a preface by Adrian Goldsworthy.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Greece and Rome at War by Peter Connolly in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Ancient History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

ITALY AND THE WESTERN MEDITERRANEAN

The Rise of Rome 800 – 275 BC

Map of Italy and the adjacent islands, 8th – 3rd centuries BC. Roman-Latin colonies are marked with a blue triangle, Greek colonies with a square, Etruscan colonies with an open triangle.

Introduction

The rise of Rome was not meteoric. It was a slow painstaking process fraught with many setbacks. It was this slow process, accompanied by long periods of consolidation, that was the main reason for the longevity of the subsequent Roman empire.

Italy was the first naturally bounded area of Europe to be unified. Neither Philip nor Alexander, nor any of their successors, established full control over the whole of Greece. It took Rome some 560 years to bring the whole of Italy under her control. Once that hegemony had been established, there was never any threat of it breaking up. Even the social war fought between Rome and her allies in the 1st century BC was not about secession but over the rights to citizenship of the non-Roman Italians. It took an external influence, the barbarian invasions more than half a millennium later, to shatter the unity of Italy.

The weaponry, organisation and tactics of the Roman army, unlike those of the Greeks, were not an invention of the Romans but the result of a process of adoption and adaptation. In order to understand the development of the Roman army it is necessary to examine the peoples the Romans fought and to try to isolate what they learned from each other.

The main source of our knowledge of this period is the Roman historian Titus Livius. Although Livy is a great writer, he is a poor historian. As a conservative and patriot he throws the blame for many of Rome’s mistakes onto the lower classes who were struggling for recognition. He regularly covers up anything that is unfavourable to Rome, shows little appreciation of topography and military tactics and freely substitutes contemporary terms for ancient ones with complete disregard for accuracy. Worst of all, however, he often transmits accounts that he must know are false.

Dionysius of Halicarnassus has left us a very full account of the early history of Rome. Although he records much the same material as Livy, he has a marginally greater appreciation of military tactics and, because he uses Greek terms, it is often easier to visualise the items he is describing. Unfortunately, his history becomes fragmentary in the early 5th century, with the result that from c. 475 to the outbreak of the first Punic war in 264 we are almost entirely at the mercy of Livy. Fortunately, we have a substantial archaeological record that helps us to build up a fairly accurate picture at least of the armour and weaponry of this early period.

The Struggle for Italy

The story of Rome starts in the middle of the 8th century – traditionally 753 BC. Rome owed her foundation to the river Tiber, for she was one of a group of hilltop villages that sprang up on the left bank of the river at its lowest crossing point, probably in an attempt to levy a toll on merchants crossing the river to trade with southern Italy.

The Tiber rises in the Apennine mountains above Arrezzo. Here also another river, the Arno, rises. The Arno flows west to enter the Tyrrhenian Sea at Pisa whilst the Tiber flows south for 200km before turning south-west to flow into the sea at Ostia. Between these two rivers was Etruria. During the 8th century the population of Etruria was dispersed into a multitude of small villages. Here a high Iron Age culture (known as Villanovan) flourished.

In the 7th century a powerful ruling class emerged in Etruria. As had happened in Greece, they united the groups of villages to form such powerful city states as Veii, Caere and Tarquinii. The Etruscans were great seafarers and may well have come to Italy by sea from the east. Their sea captains soon established a mercantile empire in the western Mediterranean where they came into conflict with other contenders for this trade: the Phoenicians operating from Carthage on the north coast of Africa; and the Greeks who had colonised the southern coasts of Italy and eastern Sicily. One such Greek colony was established at Cumae west of Naples. These Greeks began to interfere with Etruscan ships trading with the east that had to run the gauntlet of their colonies. This trade war soon developed into a bitter conflict between the two nations.

In the closing years of the 7th century the Etruscans forced their way across the Tiber, captured the Roman villages and established a land route south through Latium. They pressed on southwards into Campania, bypassing Cumae and cutting it off from the interior. In Campania they captured several of the coastal towns, including Pompeii and Sorrento, and established a large military colony at Capua just south of the river Volturno.

An Etruscan military overlord was established at Rome. He grouped the hilltop villages into a town as had been done in Etruria, and for the next hundred years under its three Etruscan rulers Rome flourished and became the chief city in Latium.

The Etruscans reached the summit of their power when they formed an alliance with the Carthaginians against their mutual enemy the Greeks and, in a sea battle off Corsica in 535 BC, forced the Phocaean Greeks to abandon their colony at Alalia and so gained control of the island.

But the Etruscan age of glory was shortlived. Although they had isolated Cumae by their thrust southwards into Campania, they had failed to bring the Greek city to its knees. In fact, in 524, they suffered a serious defeat on land at the hands of the Cumaeans. Fourteen years later, probably at the instigation of the Cumaeans, the Latins revolted and Rome expelled her Etruscan ruler, Tarquin the Proud. This revolt spelt disaster for the Etruscans as the Romans now closed the river crossing to them.

With the assistance of Tarquinii and Veii, Tarquin tried to subdue the rebels. The ensuing battle was indecisive but the fact that they had survived was sufficient for the Romans to celebrate a triumph. Lars Porsena of Clusium (Chiusi) now entered the fray. Collecting together a large force of Etruscans, allies and mercenaries he made a rapid advance on Rome, hoping to catch them unawares.

The Romans had realised that an attack was imminent and had made preparations to hold the river crossing. A fort was established on the Janiculum, a hill on the Etruscan side of the river that covered the approach to the bridge, and the citizens armed themselves to withstand the attack. In spite of their preparations they were caught off guard. The Romans never seem to have come to terms with the idea of scouting. Their history is punctuated with disasters that could easily have been avoided by proper scouting. The Etruscans approached unseen, stormed the Janiculum and advanced on the bridge. In panic the Romans turned and fled. The patriotic Livy tells how Horatius and his two companions, who curiously both have Etruscan names, heroically held back the enemy while their fellow citizens chopped down the bridge and so saved the city. But the more enlightened Romans felt forced to admit that the city fell.

The army of Porsena marched on into Latium, advancing on Aricia, the centre of the Latin resistance. The Greeks of Cumae, realising that this was their great opportunity, also took the field. Caught between the two forces, the Etruscan army was massacred.

With their land route cut the Etruscans were forced to maintain contact with their southern colonies by sea. In 474 they suffered yet another crushing defeat at the hands of the Greeks in a sea battle off Cumae, and as a result the towns of Campania were completely isolated. But fate had a trick to play; within 50 years both Etruscan Capua and Greek Cumae had fallen to the Samnites.

For a short while Rome, which had controlled Latium under her Etruscan rulers, fought desperately to hold on to her supremacy, but it was the Latins who had defeated the Etruscans and not the Romans. At the beginning of the 5th century, finding her position untenable, Rome was forced to sign the Cassian treaty of alliance with the other Latin towns as equal partners. The next 80 years were spent by the Latins fighting for their very existence against the eastern hill peoples, the Aequi and Volsci, who were being forced down into the plains of Latium by the expansion of the Samnites. These rugged mountain men had gradually forced their way southwards through the Apennines, driving all before them. In the middle of the 5th century they burst upon southern Italy, overrunning Campania, Apulia and Lucania.

Lars Porsena. the Etruscan king of Clusium (Chiusi), with his troops on the Janiculum overlooking Rome. The native Etruscans are armed with round Argive shields, the others are their allies from central and northern Italy.

In 431 the Aequi were defeated by the Latin League and the Volsci were driven back. By the closing years of the century the Latin League felt secure enough to turn its attention to southern Etruria. The Etruscans, meanwhile, had been searching for a new outlet for their trade. About 500 BC an Etruscan colony had been established at Bologna in the Po valley and a route opened up to Spina, a port at the head of the Adriatic. But, like the route to the south, this was also doomed. For some time the Celts of central Europe had been forcing their way through the Alps and settling in the Po valley. This migration gathered momentum as the century advanced so that by the end of it the Etruscans were under pressure from both north and south. Rome, now the dominant partner of the Latin League, launched an all-out attack on the Etruscan town of Veii, which capitulated after a long siege in 396 BC. The League’s pressure on southern Etruria was to have a backlash as the Etruscans, who were trying to defend two frontiers, managed to sustain neither. Less than ten years after the fall of Veii the Celts burst into Etruria and descended the Tiber valley towards Rome. At the Allia these wild men from the north crushed the legions that had been sent to oppose them and sacked the city on the hills.

It was a terrible setback for Rome and she lost her dominant position in the Latin League. Rome recovered but for the Etruscans it was the beginning of the end. The League had lost its foothold in southern Etruria and spent three years reconquering it. This reconquest brought the League into collision with Tarquinii and several other of the Etruscan cities who were becoming fearful of the growing power of the Latins. In 388 and again in 386 Tarquinii took up arms but failed to drive them back.

In 359 Tarquinii launched an invasion of Latin-controlled Etruria. Two years later Falerii joined in and the following year the rest of the Etruscan federation also took up arms. A pitiless war ensued in which both sides mercilessly massacred prisoners. Finally, in 351, the League launched an all-out offensive and brought Tarquinii and Falerii to their knees. It was difficult for the Etruscans to make a concerted effort as they were under pressure from both sides. In the north Bologna was unable to hold out and by 350 it was in Celtic hands and the Etruscan domination of the Po valley came to an end.

In the south the Volsci were still a threat to the League, which now turned and forced them into submission. The League now controlled all of western Italy from southern Etruria to northern Campania. But the question of who governed Latium – the League or Rome – remained unresolved. In 340 the final struggle began. After a bitter war lasting three years Rome emerged as undisputed master and the history of Italy now became the history of Rome.

The last war with the Volsci had brought Rome face to face with the Samnites along the Liris River. Rome had signed a treaty with them in 354 to enlist their aid against their mutual enemy, the Volsci. In 343 hostilities broke out between the two na...

Table of contents

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- Preface

- Foreword

- GREECE AND MACEDONIA

- ITALY AND THE WESTERN MEDITERRANEAN

- THE ROMAN EMPIRE

- APPENDIX I

- APPENDIX 2

- APPENDIX 3

- Acknowledgments

- Bibliography

- Index