eBook - ePub

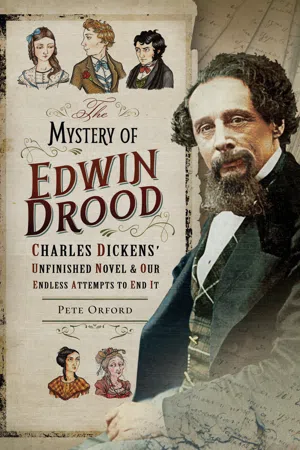

The Mystery of Edwin Drood: Charles Dickens' Unfinished Novel & Our Endless Attempts to End It

- 240 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Mystery of Edwin Drood: Charles Dickens' Unfinished Novel & Our Endless Attempts to End It

About this book

A tantalizing tour through a true bibliomystery that will "get people talking about one of literature's greatest enigmas" (KentOnline).

When Dickens died on June 9, 1870, he was halfway through writing his last book, The Mystery of Edwin Drood. Since that time, hundreds of academics, fans, authors, and playwrights have presented their own conclusion to this literary puzzler.

Step into 150 years of Dickensian speculation to see how our attitudes both to Dickens and his mystifying last work have developed. At first, enterprising authors tried to cash in on an opportunity to finish Dickens' book. Dogged attempts of early twentieth-century detectives proved Drood to be the greatest mystery of all time. Earnest academics of the mid-century reinvented Dickens as a modernist writer. Today, the glorious irreverence of modern bibliophiles reveals just how far people will go in their quest to find an ending worthy of Dickens.

Whether you are a die-hard Drood fan or new to the controversy, Dickens scholar Pete Orford guides readers through the tangled web of theories and counter-theories surrounding this great literary riddle. From novels to websites; musicals to public trials; and academic tomes to erotic fiction, one thing is certain: there is no end to the inventiveness with which we redefine Dickens' final story, and its enduring mystery.

When Dickens died on June 9, 1870, he was halfway through writing his last book, The Mystery of Edwin Drood. Since that time, hundreds of academics, fans, authors, and playwrights have presented their own conclusion to this literary puzzler.

Step into 150 years of Dickensian speculation to see how our attitudes both to Dickens and his mystifying last work have developed. At first, enterprising authors tried to cash in on an opportunity to finish Dickens' book. Dogged attempts of early twentieth-century detectives proved Drood to be the greatest mystery of all time. Earnest academics of the mid-century reinvented Dickens as a modernist writer. Today, the glorious irreverence of modern bibliophiles reveals just how far people will go in their quest to find an ending worthy of Dickens.

Whether you are a die-hard Drood fan or new to the controversy, Dickens scholar Pete Orford guides readers through the tangled web of theories and counter-theories surrounding this great literary riddle. From novels to websites; musicals to public trials; and academic tomes to erotic fiction, one thing is certain: there is no end to the inventiveness with which we redefine Dickens' final story, and its enduring mystery.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

CHAPTER ONE

Nostalgia and Opportunism: The Early Solutions 1870–1885

Famous last words

‘The Late Charles Dickens’

I

Dickens is dead. Who has not lost a friend?

Far, far too early seems this sudden end

Of one whom all men loved. The fatal hour

Arrives too soon for him,

Whose glance had not grown dim,

Whose heart and brain preserved their fresh and liberal power.

II

‘Whom the gods love, die young’ – so wise men hold:

This man dies young, who never could grow old.

Genius like his to the last hour receives

The golden gift divine;

And to the last there shine

The love within his heart, the life upon his leaves.

III

Such life. Old Chaucer was his prototype:

But Geoffrey’s verse in Charles’ prose grew ripe.

He gave us Pickwick, Quixote of the day –

Weller, the Sancho Panza

Of a new extravaganza –

Quilp, the half-human goblin, devilishly gay.

IV

Micawber, too, the strangely sanguine scamp –

The ebrious Swiveller, the garrulous Gamp –

Pecksniff’s low tricks, and Skimple’s dainty thirst:

Latest, to move our Wonder,

Crisparkle, Honeythunder –

Men whom we all have met, though DICKENS drew them first.

V

His canvas glows with many charming girls,

But surely, choicest of these pretty pearls

Is little Rosa of the cloistered City –

A wayward gay coquettish

Provoking loving pettish

Darling of life’s young spring, creature to scold and pity.

VI

Ay, the final hand! – it had not lost its cunning:

Ah! But the strong swift life-blood ceased running –

Pass quick away the pathos and the mirth:

When shall we see again

One whose creative brain

Adds such a chapter to the Bible of the Earth?8

Dickens was dead: to begin with. After working on the latest instalment of Drood on the morning of 8 June 1870, in the chalet across the road from his home in Gads Hill, he then suffered a seizure that afternoon, dying later in the early hours of the following day. The private passing of the man swiftly became the public sensation of the press, with obituaries of great sentiment and hyperbole: ‘The prince and the great man had fallen, and the shock experienced by hundreds of thousands on Thursday morning was an event never to be forgotten.’9 Several even extended to poetry, such as the entry above from The Period. Awful as the verse may be, the sentiments expressed are very much in line with several articles of the time in its depiction of Dickens as a friend of the people, his death as a personal loss for all of his readers, and his last work as promise of more of the same beloved characters: ‘ay, the final hand! – it had not lost its cunning’. This golden-hued interpretation of Drood, which would not persevere, is very much coloured by the event of his passing. The book gained great import by being his last words, which ultimately is not a reflection on the text itself but its timing.

Other contenders to Dickens’ last piece of writing were also appearing in the press. The Times reported that: ‘His last letter to the manager of All the Year Round, Mr Holdsworth, a gentleman who has been connected with Mr Dickens for a quarter of a century, was dated the day before his death, and asked him to purchase at ‘one of those Great Queen-street shops’ – who knew so well as Dickens about London brokers and their wares? – a writing-slope for Gadshill such as he had in use at the office.’10 It’s hardly the most insightful prose. Clearly, the interest of the letter lies in its context, not its content (Victorian furniture enthusiasts excepted). Similarly, John Makeham wrote excitedly to the Daily News to share a letter in his possession written by Dickens on 8 June, the publishing of which allowed Makeham a brief moment in the spotlight, which he savoured with a simpering praise that might make Uriah Heep blush: ‘I cannot but be glad to have in my possession Charles Dickens’ last words – and such words – and to be able to lay them before his thousands of admiring and mourning friends.’11 The words themselves were but a reply to Makeham’s own letter concerning a religious passage quoted in Drood (and actually Dickens’ letter is disagreeing with Makeham’s interpretation of the passage). Makeham was not a friend or confidante of Dickens but a reader being written to for the first time; that he should have, or make claim to have, ‘Dickens’ last words’ is sheer dumb luck. However, as with the unremarkable request for a writing-slope, these words gain far greater significance for Dickens’ readers simply by being amongst the last, as would prove to be the case for Drood in its unintended position as Dickens’ final novel. Where the letters of Holdsworth and Makeham are disappointingly functional and uninspiring in content, Drood has the advantage of a developed narrative that allowed early readers to probe and extract last words of wisdom or a melancholy foreshadowing of the author’s own death.

But it was not always so, and contemporary reactions to the story when it first began to appear – and Dickens was still alive and well – were quite different indeed. The first monthly part of Drood was published on Thursday 31 March 1870, and the reviews that came out of this initial instalment in April were not only positive, but exuberant. ‘Really, Messrs. Chapman and Hall!’ cried the John Bull’s review:

Please revise the announcement of Dickens’s last work! The Mystery of Edwin Drood! Of course it did, a work from the pen of Boz is always sure to draw. Please alter: – ‘the mystery of Edwin’ drew – you may add, if you like, immensely.12

Drood marked the return of Dickens to writing novels after that unprecedented five-year gap while he had been engaged on his reading tours, so, as the Illustrated London News noted in its one-paragraph review, ‘all the world is eager to welcome Mr Dickens back to the domains of serial fiction, and so far as we can judge from the first number of his work, public expectation is not likely to be disappointed’.13 The Times, in a longer review, concurred both with the sense of anticipation and the pleasant realisation that this book would live up to the hype:

The novel reading world have been on the tiptoe of expectation since the announcement of a new work by their favourite author. We have perused the first instalment, and venture to express the public pleasure, and to thank Mr Dickens for having added a zest to the season.14

The early readers did not read the book looking ahead to Dickens’ death, as we do, but looking back on Dickens’ life so far, bringing the heritage of the Dickens canon with them. Consequently, the review, not only in The Times but also in the Athenaeum, are both very nostalgic, writing respectively that:

As he delighted the fathers, so he delights the children, and this his latest effort promises to be received with interest and pleasure as widespread as those which greeted those glorious Papers which built at once the whole edifice of his fame.15

_____

It is a positive pleasure to see once more the green cover in which the world first beheld Mr Pickwick, and to find within it the opening chapters of a tale which gives promise of being worthy of the pen which sketched, with masterly hand, the course of Mr Pickwick’s fortunes.16

Not only do these reviews look back with fondness, but they link Drood back right to the beginning, with Dickens’ first full novel The Pickwick Papers – not a comparison one would expect as its lighthearted comic episodes seem a world away from the dark, murderous streets of Cloisterham. In recent years, as will be seen, it is more frequently Our Mutual Friend that is drawn upon as a comparison for Drood, as a result of the love triangles and the murder plots contained within both, and its status as the novel that immediately precedes Drood. But in 1870, the reviewers cared less for the social commentary of Our Mutual Friend and more for the popular comedy of Pickwick and the early novels, and there is a sense in which the reviewers’ identification of Drood with Pickwick speaks as much of their own preoccupations as it does of the book’s content.

At any rate, these reviewers certainly noted a much higher content of comedy in Drood than subsequent critics of the book would heed. The Illustrated London News concludes that the ‘most successful of the character portraits is Durdles’, who The Times likewise applauds as ‘a thoroughly original conception’.17 Even in the Athenaeum’s lengthier review, those scenes that we have come to think of as key in the first instalment – Jasper in the opium den, his conversation/confession with Edwin, the references to the Sapsea memorial, Jasper’s plan to visit the tombs, and the closing image of Jasper watching his nephew in the dark – prove of little interest. Just one line of the review is given to Jasper, and that is by means of discussing the comical scene with Mr Sapsea. Instead, according to the Athenaeum in April 1870, the key moments in are the high humour of Durdles, Sapsea, and the delightful scene of young Rosa and Edwin: ‘There is, moreover, a touch of the old Boz humour in that exquisitely promising Rosa Bud.’ Humour and nostalgia – this was the way in which Drood was first read.

By the time of the third instalment in June 1870, the Illustrated London News was still singling out praise for ‘the dissipated mason, Durdles’ for being ‘the only character, so far, that can be regarded as a creation, in Mr Dickens’ characteristic style’.18 Likewise, consider again that opening poem from The Period and the three characters out of the novel who it singles out for praise: Rosa, Crisparkle…and Honeythunder. The identifying of these three characters in particular shows the impact of serialised reading. Even with the fragment we now have, we still have a better idea of the whole than readers in June 1870, who only had three of the six instalments to draw on. Thus, to them, Grewgious was yet to emerge as a prime mover in the defence of Rosa; Datchery had not yet appeared; Edwin was just a spoilt young man; and Neville had yet to endure the heartache of suspicion and exile. In short, Crisparkle, the muscular Christian of cheerful manner, with his warm welcome and defence of the Landless twins, was the clear hero of the first three instalments, thus justifying his mention alongside Rosa as the heroine. But how to explain Honeythunder? Even at this early stage his contribution to the book’s plot was minimal. It is his contribution to the book’s humour that justifies his inclusion here. Like Durdles, he was a funny character. Dickens’ contemporary reviewers were predominately keen to champion such comic work and question his social satire.

But these responses in June were already fighting against the tide, for Dickens’ death that month changed the novel from his latest work to his last one, and the way it was read was irrevocably changed. In the light of Dickens’ death, readers returned to the Drood instalments with a different perspective. Increasingly, readers searched for significance in the book as it existed before them, in only three instalments, as in this letter to the Daily News:

Sir, – A short paragraph in the current number of ‘The Mystery of Edwin Drood’ has acquired a painful significance from the sad event of the 9th. Saddened as Mr Dickens must have been by the loss of so many old friends, notably by the very recent and sudden death of Maclise; the tone of thought, which dictated the few lines referred to is...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Introducing the Mystery

- Chapter One: Nostalgia and Opportunism: The early solutions 1870–1885

- Chapter Two: Clues and Conspiracies: The Drood Detectives 1878-1939

- Chapter Three: Academics vs Enthusiasts: Taking Drood Seriously 1939-1985

- Chapter Four: Music and Comedy: A return to Irreverence 1985-2018

- Conclusion: Endlessly Solving Drood

- Bibliography

- Notes

- Plate section

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access The Mystery of Edwin Drood: Charles Dickens' Unfinished Novel & Our Endless Attempts to End It by Pete Orford in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Literature & Modern British History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.