- 200 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Childhood & Death in Victorian England

About this book

A vivid and graphic survey of the casualties of childhood during the Victorian Era through detailed and never-before-seen firsthand accounts.

Take a fascinating journey into the real lives of Victorian children—how they lived, worked, played, and far too often, died before reaching adulthood. These true accounts, many of which had been hidden for more than a century, reveal the hardship and cruel conditions endured by young people living through the tumult of the Industrial Revolution. Here are the lives of a traveling fair child, an apprentice at sea, and a young trapper, as well as the children of prostitutes, servant girls, debutantes, and married women, all unified in the tragedy of early death.

Drawing on actual cases of infanticide and baby farming, historian Sarah Seaton uncovers the dismal realities of the Victorian Era's unwed mothers, whose shame at being pregnant drove them to carry out horrendous crimes. With the introduction of the New Poor Law in 1834, the future for some poor children changed—but not for the better. Yet it was the tragic loss of these many young lives that lead to essential reforms, and eventually to today's more enlightened views on childhood.

Take a fascinating journey into the real lives of Victorian children—how they lived, worked, played, and far too often, died before reaching adulthood. These true accounts, many of which had been hidden for more than a century, reveal the hardship and cruel conditions endured by young people living through the tumult of the Industrial Revolution. Here are the lives of a traveling fair child, an apprentice at sea, and a young trapper, as well as the children of prostitutes, servant girls, debutantes, and married women, all unified in the tragedy of early death.

Drawing on actual cases of infanticide and baby farming, historian Sarah Seaton uncovers the dismal realities of the Victorian Era's unwed mothers, whose shame at being pregnant drove them to carry out horrendous crimes. With the introduction of the New Poor Law in 1834, the future for some poor children changed—but not for the better. Yet it was the tragic loss of these many young lives that lead to essential reforms, and eventually to today's more enlightened views on childhood.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Childhood & Death in Victorian England by Sarah Seaton in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Modern British History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

Industrial Mishaps and Misdemeanours

The Industrial Revolution was a time of great prosperity in Britain. Market leaders in cotton, wool and other commodities, the inventors of the Victorian age pushed ever further to create ingenious machinery to drive productivity even higher. The First Industrial Revolution began around 1760, starting with new manufacturing processes in textiles, steam power and iron making, it continued through to what is termed the Second Industrial Revolution, which took place between 1840 and 1870 when even further advances were made on a much larger scale.

Where cottage industries had first thrived, they were now replaced by machines and factories situated mainly in the large towns and cities. Poverty-stricken workers had no choice but to follow the work; a study of census returns in Nottingham between 1841 and 1901 showed that many of the inmates of common lodging-houses in 1841 and 1851 tended to be whole families moving to the town to find work. Wages were low and children were encouraged to toil in often dangerous jobs to make up the family wages so that they could merely survive. During the 1830s the youngest recorded working child was four-years-old, although the average age of a child labourer was 10.

Many of the towns were ill-equipped to meet the housing needs of the newcomers; often whole families shared just one room in poorly built housing, thrown up quickly by opportunist landlords. Even the basements were let, which in some places flooded with rainwater in bad weather; inadequate housing, poor sanitation and dangerous working conditions led to the death of many. This in turn resulted in a high number of unfortunate children who ended up in the poorhouse or on relief due to the death of one or both parents.

For some of these unfortunate children, prospects became even worse; sent into the workhouse, a selection of the poor law guardians who ran these establishments used a ‘batch apprenticeship’ system that allowed them to dispatch groups of children often hundreds of miles away from home to work in mills and factories in areas such as Derbyshire, Yorkshire, Lancashire and Cumberland. London and the south of England were the most prolific at releasing numbers of children into these areas. Recent studies by Katrina Honeyman (Child Workers in England, 1780–1820: Parish Apprentices and the Making of the Early Industrial Labour Force, 2007) and Caroline Withall (University of Oxford) claimed that batch apprenticeships continued to thrive well into the 1870s. As the workhouses were financed by parish rates and run by committees of local people (Poor Law Guardians) one of their main roles was to keep costs as low as possible as most of them were overcrowded. One of the easiest ways to alleviate the cramped conditions was to farm off children who had no one to represent them. From 1845 to 1870, 244 Liverpool children aged between nine and 14 were sent to silk, worsted, flax and cotton mills, and were employed in industries such as bobbin manufacturing as part of a batch apprenticeship system, increasing their risk of death from an industrial injury.

Once in another parish, and provided they completed their apprenticeship, they then became the responsibility of that parish should they fall on hard times again (under the rules of the Settlement Act of 1662). In the early nineteenth century, it cost St Pancras Workhouse 30s. to get an apprentice indentured in the cotton industry. Compare that to the yearly cost of their upkeep within the workhouse, which amounted to four times as much and it is easy to see why so many children were sent along this pathway. The mill owner would sign a contract with the workhouse, setting out the terms and the children would sign a contract with their new employer to agree to stay apprenticed to them until they were 21. This benefitted employers immensely; for instance, adult males at Courtauld’s Mills earned 7s. 2 d. a week, whilst children under the age of 11 received only 1s. 5 d. A survey carried out in 1818 showed that half of the workers in the Manchester and Stockport cotton factories had started work before they were 10. One recorded for the Lancashire cotton mills in 1833 showed that a large proportion of workers were children and young adults.

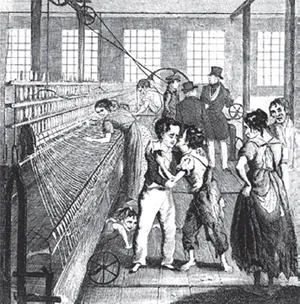

The very youngest children, from the age of four, worked as scavengers in the mills; the lowliest of the apprentices enduring the harshest of conditions. Collecting cotton wastage from the floor underneath the machinery, and cleaning up the dust and oil meant that many children suffered serious injuries whilst under the mules, with fingers, hands, and sometimes heads being crushed by the heavy moving parts. The tenters who worked the machinery were paid on what they produced, so kept the machine constantly running to improve performance. This meant that the scavengers had limited time to get under the machine, carry out their tasks and get out safely.

In 1832, John Allett, a young factory worker was interviewed by Michael Sadler and his House of Commons Committee. Allett claimed that children at the factories often worked fifteen, sixteen or eighteen hours a day. By the end of the week, after being continually on their feet, they were incredibly tired, although more accidents happened at the beginning of the day than at any other time. John reported that he had seen one child, who was working wool, get caught in the machine strap as he was hardly awake, and it carried him into the machinery. They found one limb in one place, one in another, and he was cut to bits; his whole body went in, and was mangled. At Quarry Bank Mill, Styal in Cheshire, Joseph Foden who was about 13, was the victim of an industrial accident in 1865. Whilst sweeping under a mule his head got caught between the roller beam and the carriage – as the latter was putting up – and was completely smashed. He was instantly killed.

Scavengers and piecers at work. (Source: F Trollope, Life and Adventures of Michael Armstrong, Factory Boy, London, 1840)

In 1834 apprentice James Marsland was killed whilst working at Messrs William Smith and Sons, Whitesmiths, of Wakefield. James, who was 16, was attempting to put a strap on a drum of one of their principle shafts when he became entangled. The shaft was moving at around 80 revolutions per minute, and even though it only took half a minute to extricate him from the machine, both of his arms and legs were found to be broken in many places with heavy bruising. The accident occurred on a Friday; but the unfortunate James lingered until the Sunday when he finally died in a lot of pain. A verdict of Accidental Death was recorded at his inquest which was held at the Burlington Arms, Keighley.

Sadly, accidental death at work was not confined to isolated one off incidents; some occurrences extricated a number of children from their toilsome lives. Early one morning at around 6.00 am, in March 1844, at Mason’s Mill in Bradford, the 20 horse-powered boiler of a steam engine which had just been fired up to operate a spinning mill, blew up, killing six children and injuring many others. One 15-year-old piecer, a boy named John Wilman who had been warming himself in the boiler house, was found dead about 30 yards from the furnace house, the force of the steam having carried him there. He had received severe injuries, particularly around the face. His front teeth, with one or two exceptions were gone, there was a deep gash on his face and his whole appearance was disfigured. He was carried to The Regent Inn, near to the mill and after it was ascertained that he was perfectly dead, his body was washed and laid out in a back room to await inquest.

James Booth Flaxington, another piecer, who was 13, was also very badly scalded, and he was found under a quantity of bricks, crying out in much pain. He was taken out and moved to a house opposite the mill and next to the infirmary. Mr Illingworth, employed under the factory inspectors, advised that the boy was in such a state that there was no hope of recovery. A third boy, Edward Hainsworth, 17, was taken out to the infirmary whilst Jonas Wilman, a 13-year-old piecer and brother to John, was found with the left leg broken and the right leg doubled up under him. Abraham Mitchell, another boy, was found badly scalded, parts of his skin hanging about him in tatters, but the rest of his injuries were not judged to be as severe as that of his companions so Mr Poppleton, the Union Surgeon sent him back to his home in Wapping. A girl named Garfitt was found on her hands and knees scalded and still holding her breakfast can in her hands crying out, ‘help me’. She was sent to her home in Bowling. Her brother, Thomas Thorp Garfitt, 13 ,was taken to the infirmary. Each injured child was accompanied by a cortege of people, all bearing witness to the truly shocking effects that the explosion had imposed upon the writhing and moaning bodies of the children as they were taken away.

Surgeons were assembled at the infirmary ready to use their every skill. On examination, it emerged that Flaxington had a compound fracture of the right thigh and was severely scalded over his whole body. Garfitt had three wounds on the head and was also scalded. Jonas Wilman had a compound fracture of the left leg and the limb was so shattered that it was believed to be in the boy’s best interests to amputate it, which they did just below the knee. He was severely scalded. Hainsworth was injured in two places on the head, scalded over the face, arms, neck and the right leg. An engine tenter claimed that he was not surprised at the extent of the burns as he had seen one of the boys lying in a pool of scalding hot water almost two feet deep. By 7.30 pm on the night of the accident, Flaxington, Garfitt and Wilman were dead, and Hainsworth died just before midnight. Mitchell, who had been sent home, also died leaving only the Garfitt girl alive but badly injured.

The scene at the mill was one of carnage; the ground was littered with glass, bricks, stone, slate, beams, iron rods, wheels, pipes, spindles, laths and all of the workings of the boiler and the engine. The whole of one end of the mill was ruined and the lowest estimate of the cost to repair the damage was said to be £1,000. The roof of a cottage opposite was damaged and stonework was blasted so that it became lodged in a cottage wall. Many surrounding homes were damaged on that fateful day. It appears that all of the boys, with the exception of John Wilman, were playing marbles by the firing hole of the engine when the explosion took place. Both the Garfitt and Wilman households had received a double blow that day, particularly the Wilmans at their home in the serenely named White Abbey; a local benevolent fund was set up for the relief of the parents and families of the deceased children. At the time of his death, Thomas was the only son of coal miner John and his wife Ann Garfitt; although they went on to have another son, John, a few years later. At the inquest, the cause of death was said to be the boiler bursting accidentally, casually and by misfortune.

In the 1860s injuries by machinery were the largest cause of accidental death for workers aged between 11 and 15 in industrial areas. There were numerous attempts made to improve the lives of children; the Factory Act of 1802 was followed by the Cotton Mills and Factories Act in 1819, which stated that no children under the age of nine were to be employed and that children under 16 were limited to a maximum day of sixteen hours with no working at night. However, it was almost impossible to enforce these laws unless the mill owners adopted them. Numerous other acts followed to cut down working hours. The Ten Hour Bill (also known as Sadler’s Bill) was introduced in 1832 stating that no child under nine could be employed, and those under 18 should work no more than ten hours per day with eight hours only on Saturdays. Even so, children of 14 were still working in factories right up to the Education Act of 1918 which made attending school compulsory. At the beginning of the Victorian era, the number of children working in Lancashire Cotton Mills was the highest that it had ever been.

| Age of workers in Lancashire cotton mills in 1833 | ||

| Age | Males | Females |

| Under 11 | 246 | 155 |

| 11–16 | 1,169 | 1,123 |

| 17–21 | 736 | 1,210 |

| 22–26 | 612 | 780 |

| 27–31 | 355 | 295 |

| 32–36 | 215 | 100 |

| 37–41 | 168 | 81 |

| 42–46 | 98 | 38 |

| 47–51 | 88 | 23 |

| 52–56 | 41 | 4 |

| 57–61 | 28 | 3 |

Source: http://spartacus-educational.com/IRages.htm 12/4/2016

Although some mills had medical men attached to them; other more unscrupulous employers would secrete the bodies of children away in the middle of the night to be buried later in unmarked graves in the local churchyard. Death could have been due to many things; poor sanitary living conditions, disease, accident at work or abuse. The risk to lives in the mills was immense; Dr. Ward who treated many textile workers in Manchester was interviewed about their health in 1819.

‘ When I was a surgeon in the infirmary, accidents were very often admitted to the infirmary, through the children’s hands and arms having being caught in the machinery; in many instances the muscles, and the skin is stripped down to the bone, and in some instances a finger or two might be lost. Last summer I visited Lever Street School. The number of children at that time in the school, who were employed in factories, was 106. The number of children who had received injuries from the machinery amounted to very nearly one half. There were forty-seven injured in this way.’

Many of the children who came through the poor law system to work at the factories and mills had had extremely harsh lives even before apprenticeship. Once employed, they worked long hours in the factory and often received injuries by punishment which occasionally ended in death. These were meted out by overlookers who strove to maintain a steady work pace. Corporal punishment was harshly administered for the simplest of mistakes, with beating or whipping until blood poured from the child’s back, bones were broken or the child passed out. On other occasions, heavy weights were hung about their bodies, or they were hoisted up high over working machinery in makeshift cages. Young children were hit with straps to make them work quicker and if they appeared tired, their heads could be dipped into a water cistern to wake them up. This happened to seven-year-old Jonathan Downe who reported his harsh treatment at Mr Marshall’s Factory at Shewsbury when he was interviewed in 1832 by Michael Sadler’s parliamentary committee for the government inquiry into child labour. John Birley, who had been a pauper apprentice at Cressbrook Mill in Derbyshire in the first part of the nineteenth century, described the treatment he had received at the hands of those in charge to James Rayner Stephens, owner of the radical social reform newspaper the Ashton Chronicle in 1849:

‘ Mr. Needham, the master, had five sons: Frank, Charles, Samuel, Robert and John. The sons and a man named Swann, the overlooker, used to go up and down the mill with hazzle sticks. Frank once beat me till he frightened himself. He thought he had killed me. He had struck me on the temples and knocked me dateless. He once knocked me down and threatened me with a stick. To save my head I raised my arm, which he then hit with all his might. My elbow was broken. I bear the marks, and suffer pain from it to this day, and always shall as long as I live.’

As well as implementing harsh regimes, mill owner...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Dedication

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Preface

- Introduction

- Chapter 1: Industrial Mishaps and Misdemeanours

- Chapter 2: Accidents

- Chapter 3: Poverty, Paupers and Health

- Chapter 4: Manslaughter, Murder and Circumstantial Evidence

- Chapter 5: Newborn and Early Infant Deaths

- Conclusion

- References