![]()

The Modern Age

There are troublemakers who argue that everything important that happened to the guitar happened in the 1930s, and by the end of that decade the guitar had gone from being a nineteenth-century instrument to a modern instrument in just ten years.

This is wildly inaccurate. Everything important that happened to the guitar actually happened between 1928 and 1941, and the guitar went from being a nineteenth-century instrument to a modern instrument in just fourteen years.

January 1928

Segovia played his first concert in the United States. The guitar had been largely absent from the concert stage for decades, dismissed as a trivial instrument, a kind of Spanish kazoo. Olin Downes, writing in considerable astonishment in the New York Times, described the guitarist as “the dreamer or scholar in bearing, long hair, eye-glasses, a black frock coat and neckwear of an earlier generation. He seats himself, thoughtfully, places his left foot on its rest, strikes a soft chord, then bends over his guitar and proceeds to play like the poet and master he is of that instrument.”

Downes went back to see Segovia again, as if he couldn’t trust his eyes, or his memory: “The guitar had a hundred colors, a hundred voices, including the human voice. . . . Now one heard a distant shadowy thrumming, from which a solo voice emerged, in dramatic recitative. Always the voice was a little subdued, a little ghostly, an echoing voice that might have sounded through the dust of the grave and the reveries of many ages. Or there was the spangled brilliancy and flicker, pride of race, pride of the body, the throb of the dance.”

In 1928 there was no such phrase as “classical guitar,” and it would be at least half a century before the instrument was taken seriously in classical music circles, but the fact that this slow rise to eminence happened at all was due to Segovia. He was not necessarily the greatest guitarist of his time (many consider Llobet and Barrios at least his equal) but he was the greatest evangelist for the Spanish guitar, especially in the United States, and over the next forty years he would take the country, and the world, by force.

1928

Eddie Lang started writing the book of jazz guitar. Every so often, you come across an extraordinary moment when you can hear someone mining, step by step, an entirely new gallery of expression for the guitar. Uniquely, Eddie Lang (whose birthname was Salvatore Massaro) did that twice—once with Joe Venuti, the violinist, and once with another guitarist: Lonnie Johnson.

Lang had actually invented jazz guitar back in 1922 in the men’s room of a restaurant in Atlantic City when he and his childhood friend and partner in crime Joe Venuti took breaks from playing mazurkas and polkas on stage and began improvising in the privacy of the restroom. Starting around 1928, though, Lang became the first guitarist the jazz guys would listen to and respect. Marty Grosz, a guitar student of Lang’s with a turn of phrase like a Brooklyn philosopher, said that although Lang’s rhythm was a little erratic (“He sounded like a guy running with a pie in his pants”) he was the first guitarist to bring all the sensibility and skill of the classical guitarists (he adored Segovia and recorded Rachmaninoff’s “Prelude in C# Minor”) to the popular art of jazz. He played, Grosz said, in the “simplest yet most eloquent manner, blue and melancholy as hell. It is very difficult to play lead as simply and directly as that and make it come to life, especially on guitar. Here is the real genius of Sal Massaro. This is the honest bread stick.”

Lang’s duets with Venuti were recorded on and off between 1926 and 1933. They begin almost painfully, but by the end a new musical form is up and running. At first Lang does little more than the other rhythm guitarists of his day, playing chords threaded together with little ascending or descending runs of only a handful of notes. By the end, though, he is playing solo phrases and passages, throwing in off-the-beat chordings and off-the-melody elaborations. He is the one giving each duet its conception and narrative, and his sense of harmony creates the emotional landscape of the tune. Some are little more than throwaway ideas, but as they go on Lang and Venuti are clearly starting to think less of a tune and more of a composition. The jazz guitar and jazz violin don’t sound like the odd couple any more; they sound like childhood friends.

Lonnie Johnson, a dapper, almost delicate man with a pencil mustache, was an extraordinary figure in the evolution of the American guitar, both heroic and tragic. After his early success in New Orleans and London and then the loss of his family, he moved to St. Louis, where Okeh Records ran a blues contest at the Booker T. Washington Theater. Johnson entered and won—won, he said, every week for eighteen weeks. He became in great demand as a recording artist and accompanist, able to play clean, delicate blues lines that worked with the rawest of blues shouters and the most sophisticated of jazz players. In his recordings with Armstrong and Ellington it’s fascinating to hear the space and the respect they gave him; it was said that he was the first guitarist to make the blues guitar more than just a backing but an instrument in its own right.

Johnson’s duets with Lang have the slightly stiff air of two people inventing ways to overcome their differences, but as with the Lang-Venuti duets they are groundbreaking stuff. Lang mostly plays chords, and as usual his rhythm is slightly pedestrian (not so much running with a pie in his pants here as walking with a peanut in his shoe) but his ear for harmony is exquisite; he creates the orchestra within which Johnson can improvise. Lonnie is both light and a little careful, but his bluesy feeling is infectious. He loosens Lang, and by extension the jazz guitar tradition; Lang gives complexity and thoughtfulness to the blues tradition. At times, the best of times, each man plays away from his own strengths and takes more chances, and they lift each other so much you can’t tell which is which.

Johnson went on playing his cultured nightclub jazz-inflected blues, but his was an up and down life. He went through good years of recording and admiration, and lean years of working for a railroad-tie manufacturer and later as a janitor at the Benjamin Franklin Hotel, Philadelphia. When he was “rediscovered” in 1960 as part of the folk/blues revival, he was a disappointment: instead of being a rootsy Mississippi howler he had remained as deft a nightclub jazz/blues player as ever; his favorite song was “Red Sails in the Sunset.” In the end, he moved to Canada.

Lang’s own end was more sudden and more absurd, in the existential sense, than tragic. He developed tonsillitis in 1933, by which time he was at the top of his tree, working with Bing Crosby. Crosby urged him to have his tonsils out; Lang agreed. Under anaesthetic he developed an embolism and died without regaining consciousness. The honest bread stick was gone.

1929

A banjo player named Perry Bechtel went to Martin Guitars and asked them to build him a longer-necked guitar. As a banjo player he was used to a lot of frets; virtually every guitar of the day had only twelve frets before the neck hit the body, and he felt cramped. The longer neck, he suggested to Frank Henry Martin, would make the guitar more versatile, more appealing to players in jazz bands who were doubling on, or making the switch from, banjo. Martin built him a fourteen-fret model, calling it the Orchestra model—jazz orchestra, that is, not classical. The fourteen-fret concept was so popular that it became the standard for American steel-string acoustic guitars.

1929

A wave of immigrants from Mexico revived Mexican-Californian music and culture. By 1929 over a hundred thousand newcomers from Mexico filled a vacuum in labor in Los Angeles; many were also escaping the turmoil of the Mexican Revolution of 1911–17. Their welcome was not a warm one: job discrimination was common, forcing them to work at or below subsistence levels. Death rates among Mexicans were twice those among whites; infant mortality was three times higher. To survive, Mexican colonias in rural areas and barrios in cities developed as centers for Mexican immigrants and Mexican-Americans, and in these cultural oases the traditional corrido, or ballad, not only flourished but was constantly adapted and updated to encompass contemporary hardships, very much like blues in black communities and folk ballads in poor white regions. Touring guitar professionals from Central America and South America made regular stops in Los Angeles, and Spanish-language radio and recording industries began to develop during the twenties and thirties.

In smaller towns, Latino and Latina musicians played wherever their compatriots gathered. Lydia Mendoza, who would go on to become a successful radio and recording singer/guitarist on both sides of the border, began playing twelve-string guitar with her family in restaurants and barbershops in the Lower Rio Grande Valley, and by the early thirties they found themselves in San Antonio.

“We kept on struggling for two years, singing in the Plaza de el Zacate. That [square] doesn’t exist any more—they tore it down. It was a huge open-air market. In the evenings from midnight on it was the market where all the produce trucks from the valley and everywhere would arrive. This went on from midnight until about ten or eleven in the morning. Then they’d leave, and the market would stay empty awhile. Then around seven in the evening all the folks who were going to sell food there would come in and set up restaurant tables. Each stand would set up its tables and sell chili con carne, enchiladas, and tamales—there were lots of them. There would be about twenty on each side, with a space down the middle where cars would come with people wanting to eat or hear songs, for there were a lot of groups singing in those years. . . . That was where we made our living.”

The recording companies began the same process of exploitation among the Spanish-speaking musicians that was so successful for them among rural blacks and poor whites. Lalo Guerrero, a guitarist/satirist/singer/composer/bandleader who in 1991, at the age of seventy-five, received a National Heritage Award from the National Endowment for the Arts, gave a depressingly familiar account of the business relationship.

I got paid fifty dollars a side, one hundred dollars a record. In a session I’d do two records, so I’d make two hundred dollars a session, and they wouldn’t pay us royalties . . . Hey, we argued about royalties. “No, no royalties,” and rather than not record at all, we went along . . . because I was making a name, that was what I cared about . . . But what the heck, every time I’d get two hundred dollars I’d buy my wife a washing machine, a dryer; you know, it was good for me because we weren’t making that much money. . . . I didn’t realize how much money [Imperial Records] were making until years later when Manuel Acuna, who was the A&R man there, told me. He says, “You know how much they used to make on your records? One of your records would produce as much as two or three hundred thousand dollars.”

When Fats Domino and T-Bone Walker became best sellers for Imperial, the company shifted its emphasis to black music and deleted its Mexican recording catalog.

“They canceled all of us Chicanos out,” Guerrero said. “[T]hose guys made a fortune . . . to the extent that after they got the black groups, they went higher and dropped all the Latinos or the Chicanos, and then they sold the label . . . for a million dollars, something that started with us Chicanos.”

1929

The first singing cowboys hit the road. Otto Gray was rising from his early career as a vaudeville-style trick roper to become the front man of what was probably the first full-time professional cowboy band: Otto Gray and His Oklahoma Cowboys. “Their fame spread rapidly,” Doug Green wrote in his fine book Singing in the Saddle, “and from 1929 through 1932 they tirelessly toured and broadcast in the Northeast. Traveling in huge sedans outfitted to look like railroad locomotives, complete with cowcatchers, the group became a success on the theater circuits of the era due to their dramatic showmanship—with whip and rope tricks in addition to music—their flashy costumes, and the visual humor and wide variety of their musical material.”

In 1930 the first singer-guitarist found the true spiritual home of the singing cowboys: on the air. A popular NBC radio series, “Death Valley Days,” featured John White as the Lonesome Cowboy with his guitar. When silent films gave way to “talkies,” the corral gate was open, and every bunkhouse had a hand who played guitar and sang. Even Marion Morrison, better known as John Wayne, was cast in a series of B westerns as a character called Singing Sandy, though Wayne couldn’t sing to save his life, and so had his songs dubbed.

The singing cowboy’s role in movies rapidly expanded, for the most Hollywood of all reasons: money. Cowboy guitarist Buck Jones explained, “They use songs to save money on horses, riders, and ammunition. Why, you take Gene Autry and lean him up against a tree with his guitar and let him sing three songs and you can fill up a whole reel without spending any money.”

Jones didn’t pick the example of Gene Autry at random. Autry wasn’t a cowboy at all, but a railroad telegraph operator, fired for playing his guitar on the job. In the late twenties he began a career as a singer/guitarist/yodeler in the Jimmie Rodgers mold, and over the next decade he dominated popular culture in a way that is barely imaginable today. By the mid-thirties Autry was already starring on a Sears-sponsored show called “Conqueror Record Time,” in which he played a singing cowboy. He appeared regularly on “National Barn Dance,” broadcast nationally over the NBC network, and had a gold record with “That Silver-Haired Daddy of Mine.” He also toured constantly, often playing at rodeos in which he prudently owned stock. By 1935 he was appearing in a twelve-part western–sci-fi cliffhanger radio serial called The Phantom Empire in which he—that is, Gene Autry, radio star and singing cowboy—descended every episode into the bowels of the earth to battle aliens and then made it back to the surface in order to do his weekly radio broadcast.

By then he had begun appearing in movies for Republic at the now unthinkable rate of roughly one a month. The theme song for his first full-length feature, Tumbling Tumbleweeds, became Autry’s second million-seller—and this during the Depression. Between 1934 and 1954 Autry made ninety films. Later there would be yet more star vehicles, such as a radio show called “Melody Ranch” that aired on CBS from 1940–1956, presenting the familiar formula of music, comedy, and a brief drama in which Autry saved the day. In 1942, the producers even arranged that Autry would be inducted into the military as a sergeant in the U. S. Army Air Corps during a “Melody Ranch” episode.

As Doug Green says, Autry (and many of the other characters created for the movies’ singing cowboys) “embodied a charming Depression fantasy—troubles and problems could be dispelled with songs, good cheer, and innocent honesty.” If the singing cowboys (and cowgirls) in general gave the guitar a place in America’s greatest mythic panorama, Autry gave the guitar something else it had never had before, even in the cultures where it was as commonplace as a table. Autry gave the guitar star quality. People bought guitars, or bugged their parents to buy them guitars, not just because they wanted to play music but because they wanted to feel like heroes.

One company that was very aware of this connection was Sears, Roebuck. Sears had already developed an interlocking enterprise that combined every aspect of musical advertising, production, marketing, and sales. Sears owned the powerful radio station WLS (“World’s Largest Store”) in Chicago, which broadcast the “National Barn Dance,” on which Autry became a star. Sears also sold Victrolas, Silvertone records, and radios, so it could put its artists on the radio to be heard in homes on Silvertone radio sets, thus creating the demand for Silvertone records, which would be played on Sears phonographs. Sears, which also owned the Harmony guitar company, brought out the Gene Autry Roundup guitar for under ten dollars and helped publish two Autry songbooks. Other “cowboy” guitars followed, many with campfire or mountain scenes painted or stenciled on the belly. It was the image that was the point, after all.

When Autry quit Republic in 1937, his place as studio singing cowboy was taken by Len Slye, who changed his name to Roy Rogers. Autry and Rogers, though, were just the biggest draws in a crowd of singing cowboy stars: Eddie Dean, Rex Allen, Monte Hale, Tex Hill, Tex Ritter, Jimmy Wakely. The dry hills around Los Angeles were alive with the sounds of guns firing blanks, and music.

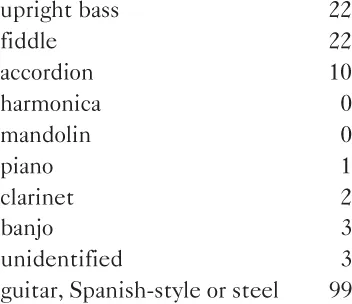

Specifically, guitar music. The photographs (most of which are publicity stills) included in Singing in the Saddle illustate how central, prominent, and ubiquitous the guitar was, how important to the identity of the singing cowboy. As far as I can make out the photos feature the following instruments.

There may be some selection bias in the choice of photos—after all, Doug Green is a guitarist, with a fondness for the big old Strombergs of the acoustic swing era—but, even so, this is a landslide win.

It bears repeating that the guitar rose to preeminence in the United States partly because of physical changes in the instrument, partly because of developments in skill and repertoire, but largely because it became associated with popular and financially viable myths. The cowboy was invented, for the most part, long after the West was settled, which is why so many western songs, like southern songs, are tinted with regret and loss. The guitar was hitched on his back to help give voice to the myth, and as the myth had to do with mobility and a hardscrabble working life, it had to be sung to a folk instrument, portable, expressive, and cheap. It’s fascinating to look at the guitar’s competitor, the piano, in westerns: it’s an eastern instrument, prissy, immobile, plunked by a comic character in a saloon and just waiting to be busted up when the barroom brawl breaks out. I can’t think of a single western in which a song sung to a piano means a damn thing.

1931

Martin relaunched the dreadnought. The original dreadnought was an oddity, a big, strangely shaped, boomy creature codesigned by Martin and a manager of the Ditson music stores and introduced in 1916 under the Ditson brand name. Dreadnoughts, nowadays often called dreads, didn’t catch on for years, and Ditson went out of business in the late twenties. In 1931 Martin incorporated the dreadnought into its line of guitars, and in time it became immensely popular in the hands of string-band players and cowboy singers. By the sixties it was a staple in country music, folk, and bluegrass.

In the same year, the first production electric guitars went on the market. Electric guitars are the grassy knoll of guitar history: everyone has a theory about what happened, in what order, many of them involving conspiracies.

The basic point is this: the Hawaiian boom produced a crisis for the guitar. For the first time, audiences en masse wanted to hear individual notes being played on a featured instrument that was too quiet for its venues. The guitar, it’s worth saying again, is by nature an intimate creature, suitable for rooms of, say, four hundred square feet—smaller, if anyone is talking. Not on...