![]()

PART I

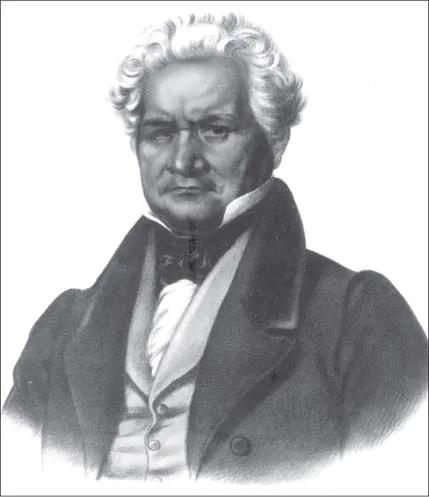

Major Ridge, c. 1834.

Illustration courtesy of the Oklahoma Historical Society Research Division.

![]()

ONE

An Old Prophecy

The sounds of battle echoed through the Tennessee Valley—shrill and staccato war cries, the crescendo of a thousand voices screaming at once.

The noise bounced off rocky mountain faces and washed over the land below, a rumpled quilt of forested hillsides and pastures of high, thick grass that rolled gently toward a wide river. When a breeze came off the water, the meadows swayed as if the very land were breathing. The drought of a few years earlier had given way to a lush summer, and the green fields nearly glowed in contrast to the dark mountains and silver-blue water where the Hiwassee met the Tennessee River.

This land was unspoiled in every direction save for a small collection of buildings that sat behind the walls of a military garrison near the riverbank, a lone outpost on the edge of the American frontier. On this day, hundreds of Cherokees were gathered outside the garrison to watch their warriors compete in a spirited version of ballplay. The object of the game was simple: two teams fought to put a ball about half the size of an apple through the opposing team’s goal, two tall poles at either end of an acre of field. Players were given cupped sticks to scoop up and carry the ball, but in truth there were no rules. The men carried the ball—usually a clump of grass tucked into deerskin—any way they could, and took it from the other team in any way possible, no matter how violent.

The pace of the game was relentless; the action stopped only when a pile of players so large and confusing accumulated that it was impossible to continue. When that happened, the men were separated, the ball was thrown into the air, and it all started again. The first team to score twelve goals won.

For the Cherokees the ballplay was serious business. They bet on the outcome in the weeks leading up to it, and talked about it for months afterward. Legend had it the tribe once won half of Georgia from the Creek Indians in a single match (the Creeks, in their version, claimed they won). The players followed strict rules in the days before a game, the most arduous of which dictated that they not lie with their women. But warriors were willing to do anything to gain the slightest advantage, to the point of smearing bear grease on their bodies to slip tackles. It was not a sport for the weak. Players were injured constantly, sometimes even killed. It was with good reason the ballplay was called anetsa, a Cherokee word that meant “the little brother of war.”

These games were scheduled for all large meetings and celebrations, and this day, August 9, 1807, was supposed to be both. Hundreds of Cherokees had come to Hiwassee Garrison to collect the tribe’s annuity from the white men. The money amounted to a yearly mortgage payment on land the Cherokees had deeded to settlers or the United States government in various treaties. There was no payoff date, and the amount changed only when a new treaty was signed or more land was sold. The white men’s Congress had promised that these payments would continue forever.

Although the money helped the tribe survive in what had become increasingly a white man’s world, the vast majority of Cherokees would have quickly, and gladly, given it all back for what they had lost. In just the past two decades, the Indians had sold nearly half of their vast ancestral lands for a modest sum of a currency that meant little or nothing to them. These annual payments amounted to barely more than a few pennies for each member of the tribe.

The newest treaty was the most troubling of all. In October of 1805, a few chiefs had sold every acre of Cherokee land north of the Tennessee River between the Holston River and Muscle Shoals. The United States would come to call this region the Cumberland Plateau, but most Indians knew it only as their hunting grounds. For those tens of thousands of acres, the Indians received $17,000 in cash and a promise of $3,000 annually—and in the bargain they lost their greatest source of wild game. The sale forced the Cherokees to take up farming, which white men had tried to impose on them for years. When news of the treaty, and the loss of their hunting grounds, first spread through the Cherokee Nation it nearly set off a tribal war. To keep the peace, the tribe’s council adopted new laws making it nearly impossible for anyone to sell Cherokee land. But enforcing these rules would prove difficult. It was clear the white men had an insatiable taste for Indian land, and a few powerful Cherokees were always eager to deal.

In recent years, the United States government had begun an aggressive campaign to convince the southern tribes to trade their homes for large tracts of land west of the Mississippi River, where President Jefferson had secured a vast frontier from the French. Indian agents bragged about the “great plains” shamelessly, claiming that this western land held the promise of bountiful hunting and no interference from whites. In truth, the government was merely promoting the interests of its constituents, new settlers who were hungry for land, caught up in the country’s great expansion. Since 1790 Tennessee’s population alone had grown from thirty-five thousand to nearly a quarter million. These families—drawn to the temperate climate and fertile ground—needed homesteads. And they didn’t want to share their new homes with the natives. It was a volatile mix of greed and prejudice.

Some Indians, weary of the endless encroachment by settlers, reluctantly accepted these government land swaps. The great majority of Cherokees, however, swore they would never consider the white man’s deal. According to tribal legend, the Creator had made man out of the red clay of the earth, and that meant the red men were the first race, the most pure. The Cherokees felt tied to their land spiritually and saw themselves as a part of its nature. They loved their land as much as the white men coveted it, and most of them would rather die than give it up.

The tension that resulted from these land deals was a cause of great concern for Return Jonathan Meigs, the local U.S. Indian agent. Although he had become accustomed to life among the Cherokees, he wasn’t sure it was a good idea for so many members of the tribe—some of them overtly hostile to the United States government—to converge on his office at Hiwassee Garrison. Many of these warriors were the same men who had murdered hundreds of settlers in the Indian wars twenty years earlier. The log walls of the garrison he’d spent $20,000 and a year building were a reminder of that history. There were still Indians who would just as soon kill whites as take their money, and that was trouble Meigs preferred to avoid. Yet despite these private fears, he was a most gracious host.

Meigs served as a diplomat between the tribe and the United States, but his job was much more complex than simply acting as an interpreter or ambassador. He was charged with keeping the peace between Indians and settlers, and with introducing the tribe to more civilized methods of survival, primarily farming and education. He prompted many Cherokees to learn the English language, to read and to write, and encouraged the women to sew and weave. He also served as judge and jury in the conflicts that arose between whites and Indians. Meigs meted out justice without any appearance of favoritism, and that had won him the respect of many Cherokees.

These days, his bosses at the U.S. War Department also frequently urged Meigs to convince the tribe to move west. They told him to bribe any chief he felt could be persuaded with a little money or a new gun. In his time, the Revolutionary War veteran had seen a great many things, and he knew his situation was not ideal. It was a patronage job, easy living for a respected war hero. An Indian agent did not carry the same prestige as an ambassador to, say, France but it was important work. Nonetheless, the problem for Meigs was that, at sixty-seven, he was too old to have his opinions dictated to him.

Living among the Cherokees, Meigs had gained a great deal of respect and sympathy for these Indians. They were a special tribe; he considered them more civilized than most of the other tribes, saw them quickly adapting to modern, European ways. Given time, the Cherokees would live almost exactly like the settlers moving into the area daily. Above all else, Meigs realized the Cherokees had been there first, that it was indeed their home. He also knew that if the United States wanted their land, the tribe’s only chance to survive might be to do as they were asked. He had lived through the frontier wars, and the old soldier realized the next time the Indians fought the U.S. Army it would be much worse for both sides.

So Meigs did as he was told and reluctantly offered kickbacks to Indians willing to deal with the government. And he found no one more willing than the old chief who showed up at the ballplay late that afternoon.

Doublehead walked with an unmistakable swagger. He was one of the most feared men in the Cherokee Nation, and he knew it. Over the years, Doublehead had killed more whites and Indians than anyone cared to count, and he had become politically powerful in the process. Few dared to cross him, and most Indians moved out of his way as he passed. But when Doublehead saw Meigs watching the ballplay with James Robertson and Daniel Smith—two U.S. commissioners—and Sam Dale, a trader from Mississippi, he displayed none of his famous temperament. He put on a great show of affection for these white men.

“Sam, you are a great liar,” Doublehead said. “You have never kept your promise to come to see me.”

He presented the group with a bottle of whiskey and soon they were drinking together, a spectacle nearly as interesting to the Indians as the ball-play. It was only further proof that Doublehead was in the pocket of the white men, and it stirred resentment among the assembled Cherokees. The old chief, it seemed, had no shame.

Doublehead brokered the 1805 treaty almost single-handedly, and the Cherokees had since learned that he’d profited handsomely from it. As a reward for selling off the tribe’s hunting grounds, the United States had given Doublehead a cash bonus and two tracts of land for himself and a relative. Instead of hiding his involvement the chief bragged that he had secured a good deal for his people. One story held that after the treaty was completed, Doublehead even demanded a bottle of whiskey—from a local missionary, no less—for all his hard work.

It had not always been that way. Years earlier, Doublehead had been one of the most loyal protectors of Cherokee land. When the Indians were practically at war with settlers in the final years of the eighteenth century, he fought as tirelessly as the legendary Dragging Canoe, and was perhaps even more relentless. For a time, he had been a hero to some Indians, hailed as their greatest protector. With the passing of those days Doublehead had not grown any less violent. It seemed he still had a taste for blood, and it did not matter whose it was. Now, he mostly fought his own people.

Doublehead was speaker of the council, an important position among the Cherokees, and some Indian agents misinterpreted this as a sign of respect. In truth, he won the job only for his talent as a storyteller and ability to translate English messages from the government, not for any recognition of great wisdom. Doublehead keenly felt this lack of respect, and it weighed on him; perhaps it is what led him to put his own desires ahead of the tribe. Even if Doublehead did not think of it in such terms, many Cherokees believed he no longer cared if the tribe lost land so long as he didn’t lose his.

Although he may not have been particularly wise, Doublehead was not stupid. He knew there was talk about the consideration—the bribes—he accepted from white men. But he didn’t care. He did as he pleased and it had made him very wealthy. He now believed that he was all powerful, perhaps even more so than the principal chief. Doublehead was confident no one would challenge him. Accordingly, he made no attempt to hide his relationship with the white men.

As the afternoon passed the group cheered on the ballplay and drank until they finished Doublehead’s whiskey. Dale offered to refill the bottle from his own supply, but the old chief preferred to play the gracious host, acting as if the entire gathering were his own private party.

“When in white man’s country, drink white man’s whiskey, but here, you must drink with Doublehead,” he said.

The ballplay ended soon after the sun fell behind the mountains. The crowd slowly wandered off in the dusk. Some Cherokees headed home and others gathered around kegs of whiskey set out by soldiers from the fort, a gesture by Meigs meant to improve relations. The game would turn into a party, Indians lingering outside the garrison walls well into the night. Finally Doublehead rose to leave, saying his good-byes to Meigs and the others, who had gathered around one of the barrels. As the chief was climbing onto his horse a Cherokee named Bone Cracker called out to him. The man had been drinking, and the liquor coursing through his blood gave him the courage to grab the bridle on Doublehead’s horse.

“You have betrayed our people,” he said. “You have sold our hunting grounds.”

Doublehead had heard these charges before, but rarely had any Indian so brazenly confronted him. Trying not to attract attention or embarrass himself in front of the white men, the old chief showed a measure of restraint. He calmly told the man to walk away.

“You have said enough. Go away or I will kill you.”

It happened in an instant. Some later said that Bone Cracker stepped toward the chief; others claimed he pulled his tomahawk, maybe even struck Doublehead with it. Either way, Doublehead reacted instantly. He pulled his pistol and shot the Cherokee at near point-blank range. Bone Cracker fell instantly and died within moments.

No one spoke. Doublehead sat there atop his horse, staring at the limp body on the ground with only mild interest. The crowd had grown quiet, but most of the Indians pretended they had not seen the killing. Many simply walked away or turned their attention to the kegs or the distant mountains, as if something else held their attention. Eventually, Doublehead gave a quick kick to his horse and rode off without a word.

Meigs and the others were astonished. Their gregarious friend had killed another man as casually as most would smack at a fly, and he did not seem to give it a thought. They took it as more proof that, in the Cherokee Nation, Doublehead was untouchable.

But he wasn’t.

More than two dozen Cherokees were already deep in their cups at McIntosh’s Long Hut tavern when Doublehead walked in that night. Situated on the trail near the tiny outpost of Calhoun, the bar—an oversize cabin, really—was a favorite among the Indians. Doublehead was a friend of the owner, another Cherokee, and the old chief spent many hours entertaining customers with outrageous stories. This evening, however, he brushed by McIntosh and the others without a word, took a seat in the back of the room, and ordered a drink. He appeared mad and most of the men, wise enough to avoid drawing his anger, left him alone.

News of the incident at Hiwassee Garrison had not yet reached the tavern. McIntosh was expecting a crowd later that night, but most Indians leaving the ballplay would travel the five or six miles between the fort and the tavern at a more leisurely—if not drunken—pace, thanks to Meigs’s hospitality. Even if they had known about the killing of Bone Cracker, no one at McIntosh’s would have said a word to the old chief. And it would not have mattered to the three men watching him from another table.

They did not need another excuse to kill Doublehead.

The men had been sent by a faction of the tribal council to assassinate their own speaker, an almost unprecedented act. James Vann, a local chief, had decided it was time Doublehead paid for his many crimes against the Cherokee Nation, and several other chiefs agreed. But there was more to Vann’s plot than simple politics; it was also personal. The trouble between the two men went back years. On a trip to Washington City in 1805, Vann had tried to stop Doublehead from selling the tribe’s hunting grounds. When he called the old chief the Cherokee’s “betrayer,” knives were drawn. The two men nearly killed each other before they were separated. To make matters worse, Doublehead had married the sister of one of Vann’s wives and then beat her to death while she was pregnant. Doublehead’s family made excuses, claimed the woman was keeping the company of another man. But Vann did not believe them and, spurred on by his wife, wanted revenge.

Vann was no innocent himself. A prosperous trader and tavern owner, he was known to liberally use his own merchandise and, even sober, had a violent temper. There were rumors that he was not above taking a bribe from Indian agents, either. The difference was Vann seemed to have the best interests of the Cherokees at heart. He aligned himself with young, progressive members of the council and was a leading advocate for farming, education, and the other accepted tools of modern civilization. Vann and his allies, including Charles Hicks, a mixed-blood Cherokee who served as Meigs’s interpreter, had become influential voices in the nation, so when they agreed it was time to do something about Doublehead it wasn’t difficult to recruit volunteers. One of them, a new council member, now sat at a table in McIntosh’s watching the old chief hold court with a few drunks. The Ridge had agreed to help Vann, but he had his own reasons. He believed justice demanded that Doublehead must die.

At thirty-six, The Ridge—as the white men called him—already had a considerable reputation for uncommon intelligence and morality. He was the son of a hunter, and his parents had believed he was destined to follow his father’s path and named him Nung-noh-hut-tar-hee, or “He who sla...