![]()

CHAPTER 1

THE EDUCATOR

ONE HAND MANEUVERED A PAINTED PAPIER-MÂCHÉ GYPSY across the stage, thumb flicking a whip in the puppet’s tiny fist. In the other hand, a brown bear danced in time to the music with each dip of my wrist. I stood below the pair, legs spread wide, my black sock-clad arms locked at the elbow. Here my five-foot, six-and-a-half-inch stature served me well. Taller men could never have managed the space—though even I stooped in the cramped black booth, my head just below the stage’s bottom border. It was imperative that I keep my head low lest my hair make a guest appearance as a hedge. Without looking up, I also had to keep straight my lefts and rights. And in that moment I could not recall whether it was my right hand or left that bore the dancing bear.

Odds are that the audience—a gaggle of young Jewish children sitting cross-legged on their school’s cafeteria-room floor—was baffled by the commanding bear and dancing gypsy that followed. That gaffe is my most vivid memory of a two-year weekend career as a puppeteer. The play’s name is gone from my memory, as are the titles of all the other goofy skits I performed for eager-eyed students at Sunday schools around New York as a part of Bubatron—theater of dolls in Hebrew.

I had found my way into the bilingual (English and Hebrew) puppet troupe by way of a good singing voice and the Theatre Department at Columbia University. There, my acting career’s first setback had been the discovery of two minor speech impediments, including a slightly sibilant s. An unfortunate onstage experience performing the work of Henrik Ibsen reinforced that the theater was not for me. The sock-handed mix-up now unfolding above my head had just confirmed it. Acting was out. But what was in?

School had not been my forte when I was growing up. Unable to do much in the way of math, I had grown accustomed to a position near the bottom of the class ranks. Even if I had been better at algebra, excelling at Midwood High, my Brooklyn alma mater, seemed impossible after my brother Elihu passed through. Three years my senior, Elihu was editor in chief of the Argus, the school newspaper, and a straight-A student on his way to Columbia. I was an underachieving high school freshman. It was an impossibly tough act to follow—so I didn’t try too hard. In fact, I just aimed to graduate. Reading trashy books, walking on the Coney Island boardwalk, and playing pool were my seventeen-year-old male modus operandi. In June 1947 I did graduate—by the skin of my teeth.

I wanted nothing to do with college, but my family insisted, so I enrolled in Long Island University. After a disheartening semester at its Brooklyn campus, my big brother came insisting. At twenty-one, he was already a success in the Sociology Department at Columbia, well on the path to graduate school and a distinguished career. But despite these grand ambitions, he hadn’t forgotten his little brother floundering back in Brooklyn. “Don’t stay at LIU, Karl,” he said. “Transfer to Columbia.”

“Yeah, right,” was my incredulous reply—until he told me how.

Columbia had just opened its School of General Studies, designed to accommodate the swell of young veterans returning from World War II. Though boasting the same professors and courses as the university’s School of Arts and Sciences, its student body was quite different. Along with GI Bill veterans, it was accepting others who had detoured along their academic route. My brother was certain there would be a spot for me. Sure enough, they accepted my transfer application, and I moved uptown.

Unpacking my bags at Columbia’s Furnald Hall, I remember feeling as if I had just entered the Ivy Leagues through the back door. Over half a century later, I still sometimes feel that I snuck into the venerable institution. But front door or back, there I was, standing inside one of the country’s best universities. And I was determined to stay.

My Columbia education began before I ever left my new dorm room. At nineteen, I’d removed myself and moved into an apartment with my brother and his friends. They were an imposing group: a world-renowned sociologist in training, a couple of Columbia Law Review guys, a future executive at the World Bank. As a freshman, trying to impress any college senior was daunting. The task was made harder by their collective brainpower. Elihu had ushered me into the pool, and I recognized that I was in the deep end. It was up to me to sink or swim.

This was both inspiring and intimidating. I wanted to show my brother that I could cut it at his university. First, I needed to find a major, and tried several departments on for size. In addition to theater, I took a crack at journalism, studied in Elihu’s Sociology Department, and even spent time penning poetry. All were wonderful, but none felt quite right. Then I sat in on a lecture by art historian Meyer Schapiro. Those ninety minutes sealed the deal. I would study art history and archaeology.

Yet, even after I found art history, and despite the gypsy/bear puppet debacle, I stayed with the puppet troupe, traveling the city on weekends with my black booth of a stage, my painted window-shades-cum-backdrops, and my papier-mâché players. It was not for love of theater or for acting ambitions, but for money. I wanted to travel abroad. Europe and Israel were waiting.

Israel had been a very real presence throughout my Brooklyn childhood. I had attended Yeshiva of Flatbush, where the day was divided between four hours of English and four hours of Hebrew. For all the secularism of the English courses—I didn’t even have to wear a kippah during that half of the day—Israel loomed large. After morning prayers, boys began pulling pennies and nickels from their pockets for Keren Kayemeth LeIsrael, the Jewish National Fund. In exchange for our coins we got postage stamps, which we proudly glued into notebooks like so many merit badges. A certain number of stamps meant a tree had been planted in Palestine. Later in the day came choir practice. Blessed with a good voice, I was the soloist in the yeshiva’s chorus. The songs—Hebrew verses about pioneers, kibbutzim, and sowing the seeds of Eretz Israel—were indelibly burned into my memory.

Israel was important at home as well. My mother was a vice president of the New York chapter of Mizrachi Woman of America, a powerful branch of the worldwide modern Orthodox women’s Zionist movement. Though my family was safe in New York during the Second World War, my father gave money to secure safe passage for an Eastern European family. The horrors of the Holocaust confirmed for my father how desperately we needed a state, and when we were old enough, my brother and I joined the Zionist cause through the Intercollegiate Zionist Federation of America (IZFA). Elihu eventually became its president; I was the art editor for its nationally circulated magazine.

ON NOVEMBER 29, 1947, my mother, father, and I sat in silence in the kitchen; with somber faces we leaned forward, heads tilted toward the radio on the Formica tabletop. We were listening to a live broadcast of the United Nations vote on the partition of Palestine. One by one, each country’s vote was announced: yes; abstention; no. My mother kept tally with pen and paper. Each time a Latin American country abstained, my father pounded his fist on the table in anguish. We needed every country we could get. At the count’s conclusion, my mother looked at her tally card: thirty-three yeses, thirteen nos, and ten abstentions. We erupted in celebration; the State of Israel was born!

IN THE SUMMER OF 1950 my puppeteering paid off and I finally made it to Jerusalem. I was touring through the three-year-old country with IZFA, whose tour guides shuttled the American college students from our high-school-classroom-cum-dormitory in Jerusalem to countryside kibbutzim and back again, making certain we admired the accomplishments of the young state along the way. They noted the hastily constructed water towers (each marking a new Israeli settlement) and the border hazards that dotted the landscape; they doled out biblical history lessons and made us brush up on our Hebrew with Sabras, the native-born Israelis. The entire country felt like a string of frontier towns. Every time we pulled into a new place, I half expected to see a sheriff’s office and general store, but we were more likely to see a machine gunner, an ancient excavation, or a tent city of recent immigrants. On each kibbutz we lived like the locals, and ate like them, too; we got the same ration as every one else in Israel: an egg a week. There wasn’t pasteurized milk or ice cream for the New York boys used to such luxuries, but we could have all the eggplants and tomatoes we wanted.

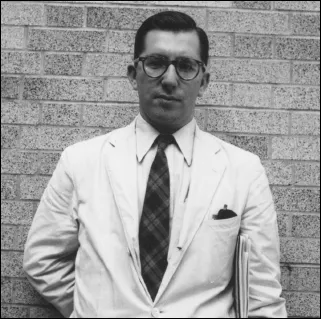

Karl as a young man. Circa 1950s.

One afternoon in Jerusalem, I slipped away from the group to visit the Bezalel National Museum. Founded in 1906, the museum took its name from Bezalel ben Uri ben Hur, the biblical artisan commissioned by God through Moses to build and decorate the Tabernacle, the menorah, and the Ark of the Covenant. The Bezalel had its home in a Turkish-style villa—a vestige of Palestine’s Ottoman period, two governments gone—and was showing its age. The building burst with a rapidly growing, and frankly uneven, collection of everything from Judaica and Western art to prints, local crafts, and Israeli fine art. The hodgepodge was the closest thing Israel had to a national general collection. As a newly minted student of art history, I wanted to see what the young country had to offer.

After cruising the cramped galleries, I introduced myself to the museum’s staff. That didn’t take long. It was a tiny group: the director, a curator of prints and drawings, a contemporary art curator, a librarian, a few administrators, and guards. As I dashed off to rejoin my group, the director, Mordechai Narkiss, said he was certain he’d see me again. My brother had just married a gorgeous Israeli soldier, an ex-sapper; she was also a pianist, and an emissary to students in the United States via IZFA. I agreed that I’d be back through Jerusalem. Little did I know I’d stay a dozen years.

AFTER THE ISRAEL IFZA tour, I headed back to New York by way of Europe with my friend Lionel Kestenbaum, hitching and traveling by train through Italy, France, Belgium, and Great Britain. Trying to stay kosher despite the lure of Italy’s sausages, France’s tournedos and frites, and England’s mystery meats proved harder than catching a ride, but we made do with loaves of bread and hunks of cheese.

In addition to stopping at cultural monuments featured in our guidebook, we spent a lot of time in antique shops. I was on the hunt for silver candelabra: my mother commissioned me to buy one, or a pair, along our route home. She trusted my taste. Ever since I was a young boy I’d squirreled away clippings from newspapers and magazines of all sorts of beautiful objects, and my recent switch to art history confirmed her faith that I had a good eye.

While scoping out the candelabra selection in countless antique shops, I also examined everything else, trying to gauge the craftsmanship and purpose, material and beauty of each object. My analyses were more intuitive than scholarly, but those long looks became the foundation of my art education and life-long love of looking and collecting.

Amid all the dusty storefronts, I finally found the perfect pair of candleholders near the Ponte Vecchio in Florence. They were superb, each with five branches. Even better was that the pieces could be disassembled and easily packed. (To a twenty-one-year-old traveling on foot, this was true beauty.) Once I decided they were “the ones,” Lionel and I quickly discovered the other half of buying antiques: negotiation. In postwar Europe, dealers were eager to take anything—dollars, silk stockings, and chocolate bars were all legal tender—and lots of it, especially from a gullible-looking pair of foreigners toting a foreign-language phrase book. Yet I was determined to get the candelabras. After three daily rounds of haggling, the price dropped to $150 for both, and the deal was done. This was my first Western art acquisition.

• • •

RETURNING TO NEW YORK, I plunged headlong into finishing my bachelor’s of arts degree and working toward a master’s in art history. After all I’d seen that summer, I had a new appreciation and a more cultivated eye for art, architecture, and archaeology. Perhaps even more important, I was working closely at Columbia with Meyer Schapiro, one of the century’s great art historians.

When I had first heard him lecture as an undergraduate, Schapiro had been at the university for nearly thirty years. He arrived in 1920, age sixteen, as a precocious polymath from Brooklyn with two well-won scholarships. Schapiro completed his undergraduate years with two degrees: one in art history and a second in philosophy. When he didn’t get into the established art history program at Princeton University (a slight that he suggested could have been anti-Semitic), Schapiro decided to stay at Columbia for his doctoral work on Romanesque sculpture. His was the first art history PhD earned at Columbia, but his doctoral years were more notable for their groundbreaking approach. His dissertation, completed in 1929, was unlike any other scholarship being produced. He wrote on the cloister portal of the abbey at Moissac, whose eleventh-century relief sculptures are among the oldest and most important extant Romanesque sculptures in France. Along with art history’s standard discussion of iconography and chronology, Schapiro brought everything from illuminated religious manuscripts to medieval social history into his analysis of the doorway.

Even before Schapiro completed his dissertation, his extensive research and eloquent argument earned him an appointment as a lecturer in art history at Columbia in 1928. Three years later, an excerpt of his finished work ran in the Art Bulletin, a scholarly art publication. No one had read anything like it before.

After establishing himself as a formidable expert on Romanesque sculpture, Schapiro developed a second expertise as a scholar of modern art. He believed that in the span of nine centuries between the Romanesque and Rothko, all Western forms were interconnected, and that his role as educator was to mediate that ocean of information and bring those corresponding pieces together. His students spanned a wide range as well, from doctoral students uptown to the artists and writers who attended his lectures downtown at the New School for Social Research.

Although Schapiro wrote sparingly during his fifty years at Columbia—he only published a handful of books before retiring in 1973—his standing-room-only lectures were legendary. He was known for his own particular breed of “no notes” oration: a discussion that started with a clearly stated summation and then spiraled up and out, pulling from as many fields as he had fingers. Connections were made like so many synapses firing—everything from psychoanalysis and religion to political science and semiotics—and by the hour’s end, I often didn’t know what I was supposed to know.

ONE AFTERNOON, I WAS walking down a hallway in Schermerhorn, the Art History Department’s home, when Schapiro summoned me into his office with a demanding, “Katz!”

I stepped inside. The lights were low, the projector humming. “Please identify the slides displayed on the screen.” He clicked the machine. The first slide slid into place. I had no idea what was coming—with Schapiro, it could’ve been anything from a prehistoric cave painting to a Hans Hofmann canvas! I swallowed hard and recognized the first picture. Then I nailed the second. A couple of images in, a slide of a staircase came up. I remember thinking that it could’ve been any staircase in the world, and my dry-mouth response was, “I think it’s Bauhaus or something.”

Schapiro considered the image, and my response. “No. It’s from the Palace of Minos at Knossos, and it’s about 1900 BC.” I waited for the ax to fall as he turned to me. “But it uses approximately the same proportions of rise and tread, so I won’t fault you on that one.”

I was relieved to get out of the session with my ego intact. As admired as he was by the students, Schapiro had a reputation as remote and hypercritical one-on-one. He was impossibly demanding of his students, and because of that notoriety, many steered clear of him for their graduate work. I was no different: I was scared as hell every time he looked at me, ready to be grilled with another question I couldn’t answer, another set of stairs I couldn’t identify.

But I also knew he’d be the right adviser for my work. I was writing my thesis on early Hebrew manuscripts from Yemen. Among his other studies, Schapiro had researched an array of illuminated manuscripts, including Ireland’s prized Book of Kells and the famously apocalyptic Beatus Manuscript from Romanesque Spain. His expertise and research would be invaluable, so I took a deep breath and stepped back into his office.

Titled The Survival of Byzantine Ornaments in South Arabian Manuscripts, my thesis turned out to be much more interesting than its title implies. Yemen was still a very remote place in t...