![]()

dp n="18" folio="" ? 1

The Tourists

The Canadians arrived on different flights from different cities. Young, fit, and well dressed, they looked the part—Westerners with deep pockets dropping in to see Jordan’s jewels . . . wondrous Nabatean ruins at Petra; stunning Roman relics at Jerash; and the desert wilds of Wadi Rum, where David Lean and Peter O’Toole created the cinema classic Lawrence of Arabia. If there was time, perhaps a beachside party at Aqaba on the Red Sea.

In September 1997, in the madness of the Middle East, Jordan was a pocket of relative peace. Usually a few tourists bobbed up among the suited foreign-business and white-robed-Arab traffic at Amman’s Queen Alia Airport and the Canadians were quickly swallowed by the anonymous chaos of the arrivals hall. Immigration officials perfunctorily stamped their passports; half an hour later, all five were downtown, piling out of a couple of battered taxis in the paved forecourt of the Intercontinental Hotel. Checking in, they again presented Canadian papers and chatted easily with a desk clerk about which of the tourist attractions were within easy striking distance of Amman.

Only later, when all assembled in one of their rooms, did they abandon the pretense. These “Canadian tourists” were agents for Mossad, the fabled Israeli intelligence service. Their mission in this quiet, U.S.-friendly Arab city was state-sanctioned assassination—in the name of Israel.

With the door chained from the inside, they dropped the phony accents and spoke in their own language. Unpacking their gear, they sat for one last time, methodically rehearsing the deadly detail and schedule for the coming days. They ignored the minibar. But, instinctively cautious in a part of the world where selected guests were assigned rooms expensively rigged for others to eavesdrop, they turned up the volume on the TV.

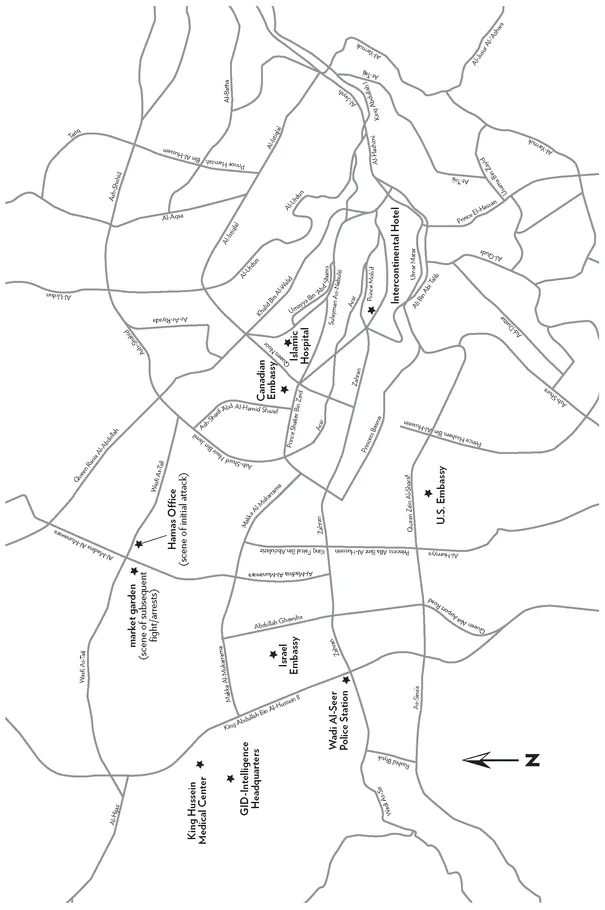

A glass-topped coffee table became a workbench on which they spread the essentials of death. A street map of Amman, with hand-drawn circles on a west-side business district. Photographs of their intended victim, who was a forty-something Arab male—lean, round faced, and bearded. Few in Jordan, or Israel, would have recognized him. Oddly, there was a small camera too.

A practiced nonchalance masked caution and anxiety in all five of them. One of the men—blond and bearded—handled the camera with a care and respect that went way beyond any ordinary tourist’s concern for holiday snapshots. The camera, in fact, was the killers’ “gun.”

One of his colleagues produced a pouch, from which he extracted a small and seemingly innocuous bottle that had been brought into the country separately and delivered to them at the hotel by a secret courier. It contained a small quantity of a clear liquid—Mossad’s “bullet.” This was a chemically modified version of fentanyl, a widely used painkiller. But in this potent, altered form it would kill within forty-eight hours, leaving no trace for discovery on the autopsy table. Their plan was murder—silent, unseen.

In the privacy of another room in the same hotel, a handsome brunette opened a small makeup bag to assure herself yet again that one bottle in particular had traveled well. She was the Mossad men’s insurance policy.

Her inclusion in the plot was most unusual, but so lethal was the drug the agents would be using for the first time that Mossad’s mission planners had demanded the presence of a doctor and an antidote in case one of the team accidentally exposed himself to the poison.

Their orders were to kill Khalid Mishal. The forty-one-year-old Palestinian activist had been overlooked by the legion of foreign intelligence agents operating in Amman. But at the Mossad bunker near Tel Aviv, Mishal was seen as the first of a dangerous new breed of fundamentalist leaders. He was hard-line, but he did not wear a scraggy beard or wrap himself in robes. Mishal wore a suit and, as the man accused by Israel of orchestrating a new rash of suicide bombs, he was, by regional standards, coherent in his television appearances. From the Israeli perspective Khalid Mishal was too credible as an emerging leader of Hamas, persuasive even. He had to be taken out.

They struck on Thursday, September 25, 1997. It was just after ten AM—and they botched everything. Had they been successful, Mishal would have gone home and died quietly; the agents would have been on their way home too, over the Allenby Bridge on the Jordan River and back in Jerusalem for a celebratory lunch. Instead, two of the Israelis were soon languishing in dank cells under an Amman security complex and the others were hunkering at the Israeli Embassy—which, incredibly for a supposedly friendly foreign mission, was locked down by a menacing cordon of Jordanian troops.

King Hussein of Jordan could rise to the occasion in a crisis. Filled with rage, he fired a shot across the Israeli prime minister’s bow, warning Benjamin Netanyahu that his Mossad men would hang if Mishal died.

More deliberately, Hussein then picked up a phone and placed a call. It was answered across the world, where a woman with a sweet voice answered: “Good morning. Welcome to the White House.”

dp n="21" folio="4" ?

![]()

2

Village of the Sheikhs

The young boy knew this truck. In the summer it delivered fleshy watermelons to stalls in the village market. Now Khalid Mishal and dozens of his stricken relatives were dumped on the back, where he was more accustomed to seeing fruit piled up like great green boulders. His mother, Fatima, was distracted, but he clung to her. Some of his aunts sat on the hard boards; cousins were squished between fat suitcases and bundles of bedding and other effects, which were held together in knotted blankets and bedsheets.

Heading east and away from their homes in the Jerusalem Mountains, they descended into an alien, inhospitable world. As the old truck lurched into the furnace of the Jordan Valley, the fertile familiarity of a village that had been the boy’s entire world gave way to desolation—an arid, bone-dry moonscape.

As they made their way toward the Allenby Bridge, the crossing just north of where the indolent Jordan River fused with the glycerine depths of the Dead Sea, Khalid saw his first war dead—the bodies of fighters on the road. Taking it all in with a child’s eyes, Khalid did not understand that, amidst this grief and sorrow, he and his family were being detached from their homeland. It was June 1967.

The traffic was chaotic. Trucks and taxis were bumper-to-bumper. Many other people were fleeing on foot. Hungry and thirsty in the heat of early summer, some wearily abandoned their baggage—suitcases and even a prosthetic leg were dumped along the way. Mothers with two-year-olds screaming for water could be seen. U.S. diplomats later estimated that tens of thousands had fled ancient Jericho alone.1

In the grim aftermath of the Six-Day War, Palestinians were repeating their own history. Just two weeks after Israel’s snap conquest of the West Bank, Khalid was now another anonymous youngster in the second wave of Palestinians driven from their land. The first had been almost twenty years before, back in 1948, when so many were forced out to make way for the new state of Israel.

Fatima now ordered her teenage girls to keep a tight hold of five-year-old Maher, Khalid’s younger brother. Yelling over the noise of the rattling truck on which they found themselves, she attempted to give the frightened children a simple explanation for this upheaval. “The Jews have taken our land,” she said.

As they finally reached the river crossing, there was congestion and more panic when all were forced to abandon their vehicles. The old Allenby Bridge had been bombed and gaping holes in the timber planking made it impassable to cars. Now ropes were strung up as makeshift handrails, to assist the thousands of refugees as they carefully made their way across the splintered pathways that remained at the sturdier edges of the bridge’s deck. Fatima and her children left their homeland on foot, inching across the river into Jordan.

Silwad was nestled in chalky high country in the heart of the West Bank. At the end of a track to nowhere, sixteen miles north of Jerusalem, about eight thousand people lived in a hillside pastoral that marked them as villagers—it was their relationship to the land, not their numbers that defined them.

The village straggled along a stoop-shouldered ridge running north–south. In front of its villagers lay a spectacular bird’s-eye view of what, after the calamity of 1948, were the lost lands of Palestine—the coastal plains from Jaffa to Haifa. Behind them rose the lofty bulk of Al-Asour Mountain, which, at 3,370 feet, was the West Bank’s second highest peak.

Silwad had been spared much of the bloodiness and brutality that shrunk the land of Palestine. But Khalid’s father, Abd Al-Qadir, had left the village, as an eighteen-year-old, to find it. He had been riveted by the sermons of the firebrand preacher Izzadin Qassam, which he listened to at Al-Istiqlal Mosque in Haifa—the northern port city to which many young Silwadis went in search of work. In 1936 he had joined the ranks of the much-romanticized, but ill-fated, Arab Revolt against colonial British forces in the Arabs’ attempt to preempt British support for the proposed state of Israel. In this uprising, which fueled Palestinian nationalism, Abd Al-Qadir sometimes fought with up to a hundred men; at other times, he roamed in a small guerrilla cell.

dp n="23" folio="6" ?London had won control of Greater Palestine when the First World War’s victors had carved up the Ottoman Empire. Thousands of Arabs died as their insurrection was brutally crushed by the British. When the revolt petered out in 1939, Abd Al-Qadir returned to Silwad with a new sense of the Palestinians’ isolation and a deep disquiet about the failings of his people’s fractured leadership. In the face of a persistent, British-backed push by the Jews for Palestinian lands, the Syrians had passed weapons and ammunition to the Palestinians, but the Arab leaders of the day had offered scant support and done little to help unite the bickering Palestinian leadership.

Amidst a rising sense of foreboding about Jewish ambitions, life in Silwad had continued for Abd Al-Qadir and his extended family of field workers and artisans. He had married Fatima, his first cousin and at that time a mere twelve-year-old, and together they had settled into a simple, if harsh, life.

Silwad was a bare-bones village with no electricity. There was just a single phone, which was locked away in the municipality office; water was drawn from the wells; and each family’s only transport usually was a single donkey. Some here were wealthier than others, but the subsistence realities of life created a simple local egalitarianism—all cooked their bread on a hot steel dome, and all spread it with the same local tomatoes, homemade cheese, and olive oil for lunch. Such was the life of a Palestinian peasant.

Here, the children accepted as normal each family’s deep engagement with recent Palestinian history, the sometimes coarse tribal ways, and the deeply conservative culture. In the same way, they took for granted the privations of a depressed rural economy that saw men go abroad for years at a time, working to supplement meager family funds. It was women who raised the families and crops. When Khalid was just fourteen months old, his father all but disappeared from his life—to distant Kuwait, sending back a few dinars each month. Sometimes the gap between his visits home was as long as two years.

For all that, there was a sense of security. Life was good. Their home was a single room, just twenty feet square, which had been walled off at the end of a building made of uncompromising gray stone. The rest of the structure was home to others in their extended family. Translated from the Islamic calendar to the Judeo-Christian, the dated keystone in the lintel read 1944.

More important than the house, however, were the salt-and-pepper fields of clay and broken limestone that came with it. Abd Al-Qadir was fortunate to have had a well-to-do grandfather who, on his death, bequeathed him forty dunams—about ten acres.2 In these rough-terraced, boulder-strewn fields the family grew wheat, fruit, and nuts—olives, figs, apricots, grapes, and almonds. In her husband’s absence, it was Fatima who marshaled her brood to work the fields between household chores and classes at a small local school, which was a walk of just more than a mile from their home in a spartan quarter of the village called Ras Ali.

Silwad was known as the “village of the sheikhs” because a long tradition of local men had undertaken spiritual studies at Al-Azhar, Cairo’s fabled Islamic university. Most returned to the Jerusalem Mountains to preach and teach. They included the blind Sheikh Khalil Ayyad, who had a powerful hand in shaping Silwad’s strict religious character at a time when Abd Al-Qadir and Fatima were finding their feet, somewhere about the middle of the local pecking order—socially and economically.

Abd Al-Qadir had a decent piece of land and, by local standards, a reasonable income. He was a restless man, often on the move, seeking the time of key political and religious figures. He had had only a brief, elementary school education, but he took to studying the Qur’an and in time his services were sought as a mediator, settling local disputes according to the tenets of Sharia or Islamic law. Fatima could neither read nor write, but she was philosophical, telling her husband, “We’re not a wealthy family, but we have wealth in our brains.”

After the 1930s revolt, violence had escalated—Arab on Jew, Jew on Arab. As Abd Al-Qadir saw it, the vacillating British were virtually giving Palestinian land to the Jews. “Piece by piece . . . in front of our eyes,” he would say. Like the Palestinians, Jewish fighters had taken to attacking the British forces as Palestinians were shunted aside to make way for a new Jewish homeland. Against rising tension, it was the Jewish underground militias, the Irgun and the Stern Gang, that had created a specter that would haunt both peoples for decades—of deliberate and lethal attacks on civilian crowds. Arab fighters had gone on the attack with “the knife, the bludgeon and the fuel-doused rag,” but the Jewish response had been the introduction to the conflict of the standard equipment of modern terrorism—“the camouflaged bomb in the marketplace and bus station, the car and truck bomb and the drive-by shooting with automatic weapons.”3

In 1945, as the world reeled from the horror of the atrocities to which the Nazis and their supporters subjected the Jews of Europe, the Zionists went for broke in their campaign for a homeland of their own, demanding all of historic Palestine.4 The emerging Cold War powers, Washington and Moscow, ignored Arab protests and, in November 1947, the United States and the Soviet Union backed a UN resolution calling for Palestine to be divided between the two peoples—with the exception of the holy city of Jerusalem, which U.N. Resolution 181 proposed be put under international control and accessible to Muslims, Jews, and Christians.

Inspired by an Islamist speaker who came to Silwad from Cairo in 1946, Abd Al-Qadir joined the Muslim Brotherhood—known in Arabic as “Ikhwan Al-Muslimun.” The Brotherhood was a controversial group, established in Egypt in the 1920s to counter secular trends and to push for religiously oriented Muslim societies that would live by Sharia law. The Brotherhood was drawn to Palestine by the Arab Revolt.5 Later it sent fighters to help the Arab resistance against the Jews and the British. It opened dozens of branches, and in Silwad most religious figures signed up—as much for political as religious reasons.

As Israel’s War of Independence loomed, Abd Al-Qadir took up arms again. But he chose not to fight with the Brotherhood. Instead he went under the command of Abd Al-Qadir Al-Husseini, a legendary resistance leader who died as a Palestinian hero in heavy fighting at Qastal, west of Jerusalem, just weeks before the proclamation of the state of Israel in May 1948.

In the weeks before his death, Al-Husseini’s paramilitaries so thwarted Jewish fighters in battles for control of steep hills on the strategic road between Tel Aviv and Jerusalem that the Haganah, the Zionist fighting force, devised what it called “Plan D.” With the objective of clearing hostile and potentially troublesome Arabs out of Palestine, this ...