- 296 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

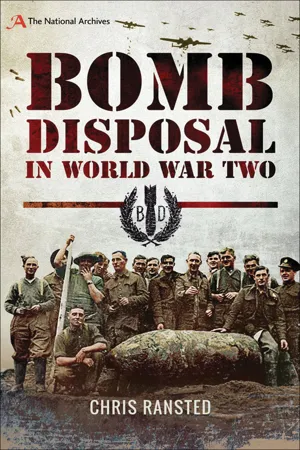

Bomb Disposal in World War Two

About this book

For this book, Chris Ransted has researched some of the lesser known events and personalities relating to the early years of Explosive Ordnance Disposal in the UK. Daring acts of cold blooded bravery, and ingenuity in the face of life threatening technical challenges, are recounted throughout the book.Included are numerous previously unpublished accounts and photographs that describe the disarming of German bombs, parachute mines, and even allied bombs found at aircraft crash sites. In addition, the book contains the most comprehensive account ever published of the Home Guards role with the Auxiliary Bomb Disposal Units, and details of conscientious objectors involvement with unexploded bombs.This is not only a valuable research tool for serious researchers already well read on the subject, but also a fascinating read for those with no previous knowledge of wartime bomb disposal at all, and of course a must read for anyone interested in the subject.

Trusted by 375,005 students

Access to over 1 million titles for a fair monthly price.

Study more efficiently using our study tools.

Information

Chapter 1

Allied Bombs

It was not just enemy bombs that the men of Bomb Disposal had to deal with. There were times when allied aircraft jettisoned their bombs over the UK. There were also those found among the wreckage of crashed aircraft, not to mention anti-aircraft shells that never went off and fell back to earth.

The majority of allied bombs were dealt with by the RAF as they were responsible for bombs at crash sites and their armourers were familiar with the different types of fuzes in use. There was some overlap however, as some aircraft carried naval weapons such as depth charges or mines and these were dealt with by the Royal Navy. The Navy were also responsible for bombs in tidal areas or on their own property. The Royal Engineers also at times got involved with allied ordnance as it was not always apparent whether a bomb was of allied or enemy origin until it had been dug out. They were also useful if the excavation for a bomb requiring specialist engineering skills or equipment. The United States Army Air Force also had bomb disposal personnel serving at their UK bases to deal with incidents involving their bombs.

Allied bombs featured both fuzes and pistols as mechanisms for initiating detonation. They could be just as dangerous, if not more so, than the Germans’ fuzes.

A pistol is an initiating device that does not contain any explosives (primer or detonator). Fuzes on the other hand do contain primers, detonators and possibly a booster charge, as a complete unit.5

The Allies’ bombs employed airburst, impact, short delay and long delay functions. Some also contained booby traps.

One of the pistols that was a great cause of concern to BD personnel on both sides was the British No. 37 Pistol. This was a chemical long-delay pistol with an anti-withdrawal feature.

As a bomb fitted with a No. 37 pistol was dropped from an aircraft, a wire was pulled out of the pistol and the arming vanes, like small propellers, were able to rotate as the bomb fell through the air. These rotating vanes screwed in an arming spindle that compressed a glass ampule containing acetone. Under pressure this ampule shattered allowing the acetone to run onto a celluloid disc that was holding back a spring-loaded striker. The acetone slowly dissolved the disc and it eventually failed, at which point the striker was driven into the detonator, exploding the bomb. The time taken by the acetone to eat through the disc determined the time delay.

This pistol was originally designed so that any attempt to unscrew it from the bomb would shear off the top, leaving the main body of the pistol in the bomb. In addition, the action of unscrewing it also allowed the spring-loaded striker to function, detonating the bomb.

The British No. 37 Pistol had a reputation among bomb disposal personnel as being a tricky one to deal with. (Courtesy of the National Archives WO 204/5987)

(Courtesy of US Navy)

In Italy on 8 January 1944, a number of men from No. 43 BD Section Royal Engineers were killed while working on a British 500lb bomb fitted with a 37 pistol.6 Dennis Abrey was a member of the section. His comments regarding this incident throw some light on the difficulties faced: ‘At Salerno six men of the 43rd Bomb Disposal Section died from a British bomb. The main cause was that the Ministry of War officials would not let our bomb disposal teams know how to defuze our own bombs. The excuse given was that if we were taken prisoner by the Germans they would force these secrets out of us. What a load of cobblers!’7

Members of No. 43 BD Section outside Rimini Station, Italy. Dennis Abrey is seated on the left. (Author’s collection)

There were actually seven men killed by that bomb on that January morning. They were:

Lieutenant Brian Malcolm MacDonald Sinclair

Sergeant Horace Evans, 32

Corporal James Archibald Johnston, 24

Sapper Francis George Biddle, 28

Sapper George William Rice, 28

Sapper Patrick Carney, 26

Sapper Willie Pearn, 24

Below are details of a number of instances where allied bombs were dealt with in the UK:

Newmarket, near Rowleymile Aerodrome

At 1230 hours on 6 March 1943, a report was received by the Air Ministry from a Flying Officer Christal, the officer in charge of No. 47 Bomb Disposal Squad. It stated that a 1,000lb bomb fitted with a 37D Mk IV long-delay pistol had become detached from a Stirling bomber that had crashed near Rowleymile aerodrome while taking off the night before.

The tail unit of the bomb, which was on the surface and about forty yards from the crashed aircraft, had been torn off, but the station armament officer had made an examination and thought the ampule inside was still intact. As a precaution, Flying Officer Christal stopped all work at the crash site and instructed the station armament officer to define a three hundred yard radius danger area and to post sentries. He then carried out his own reconnaissance and at 1450 hours confirmed the above information.

In the meantime, a prototype piece of BD apparatus was assembled at Kidbrooke, an RAF equipment store in London, and at 1610 hours Wing Commander Rowlands and Flight Lieutenant Scamell from the Air Ministry and Warrant Officer Stevens from Experimental Bomb Disposal Unit, Kidbrooke, left London by car with this equipment. The car they were in must have been driving flat out, as they arrived at Newmarket at 1730 hours. Immediately they were taken to the scene of the incident by Flying Officer Christal and his squad.

Flight Lieutenant Scamell (below) and Wing Commander Rowlands (above) were both involved in the first attempt at rendering safe a British bomb fitted with a No. 37 Pistol, near Rowleymile aerodrome. (Courtesy of Anne Vafadari and the National Archives AIR 2/9185)

From an external examination of the No. 37 pistol it could not be certain whether or not it had sustained damage. The bomb could not be accepted back into service while fuzed with this long-delay pistol, and they did not want to waste a good bomb by blowing it up. If disarmed it could be taken in another bomber heading for Germany. It was therefore decided to attempt to remove the pistol.

A three-ton lorry was driven near the bomb and a wire cable was attached. Then the bomb was towed into a depression at a safe distance from the salvageable crashed aircraft which, incidentally, was still loaded with incendiary bombs. This was the first time an attempt had been made to render safe and remove a No. 37 pistol complete with its anti-removal device from a bomb.

Considerable care was taken in manipulating the necessary apparatus and operations were further complicated by the fact that they were carried out in darkness and using a torch only.

Eventually, and after some difficulties had been encountered, the complete pistol was removed from the bomb by 2030 hours and the bomb transported to Duxford.8 The record does not state the details of the prototype BD equipment used, but it is thought likely to have been a rocket wrench. These were a metal Catherine wheel affair that clamped onto the pistol. When fired, two jets spun the tool at an incredible speed, unscrewing the fuze. It was estimated that the No. 37 Pistol would have to be unscrewed in about three milliseconds!9 At the least, the withdrawal should be so quick that even if the striker impacted the detonator, its force would be reduced by the centrifugal force and the detonator would fail to fire. Having the right equipment had a lot to do with the successful outcome of dealing with UXBs.

Kirmington and Mildenhall, Lincolnshire and Suffolk.

At 1135 hours on 30 March 1943 a report was received by the Air Ministry from 27 BD Section Lindholme that a 500lb General Purpose bomb fitted with an 845 anti-disturbance nose fuze and a No. 37 long-delay tail pistol had been dropped on the main runway of RAF Kirmington at 0200 hours earlier that day. Bomb Disposal personnel surrounded the bomb with sandbags and all the usual safety precautions were taken.

This information was received at the Air Ministry just before the departure of Wing Commander Rowlands and Flight Lieutenant Wilson to a similar incident at Mildenhall, and it was decided that the Kirmington bomb would be dealt with by them immediately the Mildenhall bomb had been rendered safe, since the Mildenhall bomb had a 36-hour delay and the Kirmington bomb a-144 hour delay.

The two men finished at Mildenhall at 1100 hours on 31 March and arrived at Kirmington at 1630 hours. Number 10 BD Section were instructed to proceed immediately to Kirmington to assist and arrived there at 1700 hours.

From an inspection of the bomb, and the fact that it had fallen through the bomb doors as the aircraft landed from an operational flight, it was thought probable that the 845 fuze was not armed.

The 845 fuze contained a sensitive mercury tilt switch that would connect a 1.5-volt battery with an igniter, should the bomb be moved after impact. The mercury when disturbed would move to connect a circuit causing the bomb to explode. An armed fuze was recognisable by the arming vanes being unscrewed or completely missing. They were designed to shear off once the spindle had reached its maximum number of rotations.

The 845 fuze. (Courtesy of David Andrews)

Having taken all necessary precautions to safeguard personnel and property, the bomb was given a ‘jerk test’, using about 800 yards of cable between the bomb and a petrol tanker.

The bomb failed to go off so Wing Commander Rowlands removed the No. 845 anti-disturbance fuze by hand, as circumstances rendered it impossible to remove it in any other way.

The No. 37 long-delay tail pistol, complete with its anti-withdrawal device, was then successfully removed from the bomb, after having transported the bomb to a site remote from aircraft and buildings. The operation was successfully completed at 2200 hours, when notification of relaxation of safety precautions was given over the station tannoy.

The bomb was removed to the station armoury at Binbrook and the detonators demolished the following morning.10

Bracebridge, Lincolnshire

A Halifax bomber, serial number HR785, of 158 Squadron took off from Lisset airfield at 2311 hours on 21 June 1943 to take part in a bombing raid on Krefeld, Germany. An hour and a half later workmen in a brickfield near Lincoln heard a screaming engine noise and the sound of cracking from an aircraft overhead. They then saw the aircraft spin down and crash about a quarter of a mile away, bursting into flames on impact.11

The aircraft still had bombs on board – two 1,000lb General Purpose bombs of which one was fuzed 845 nose and 37 tail (36-hour delay) and the other fuzed 26 tail, together with 630 x 4lb and 48 x 30lb incendiaries.

For some time it was not possible to approach the crash site due to the flames. The aircraft initially sat level on the ground and the pilot could be seen in an upright position at the controls. All the crew ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- Chapter 1 – Allied Bombs

- Chapter 2 – German Bombs

- Chapter 3 – Mine Disposal Operations

- Chapter 4 – The German Butterfly Bomb

- Chapter 5 – Searching for a Man Named Smith

- Chapter 6 – Home Guard and Auxiliary Bomb Disposal Units

- Chapter 7 – Conchies

- Chapter 8 – Clandestine Connections

- Chapter 9 – One Man’s War – Squadron Leader Kenneth Scamell

- Chapter 10 – Origins of the Second World War Bomb Disposal Badge

- Appendices

- Notes

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Bomb Disposal in World War Two by Chris Ransted in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Military Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.