![]()

Chapter 1

Winchester

Power, glory and dead Saxon kings

Winchester Cathedral. (© Bernadette Fallon)

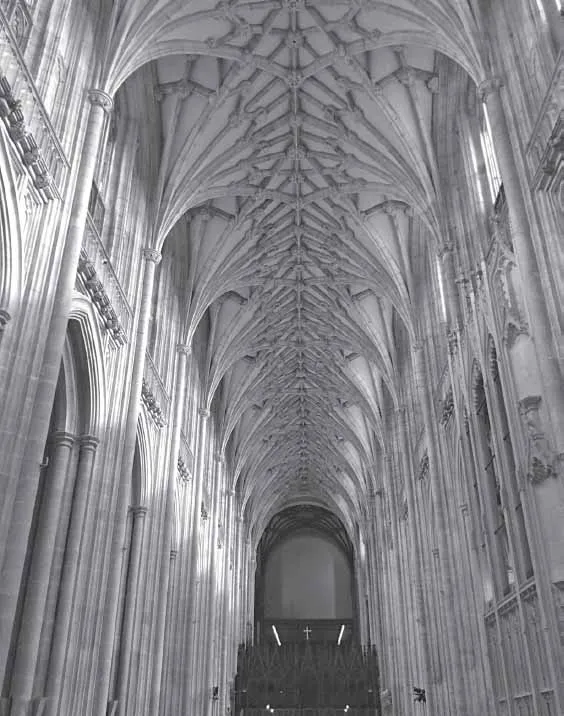

Winchester Cathedral is vast. It is the longest cathedral in Britain, stretching 169m from the west entrance to the east end, and one of the biggest medieval churches in the world. Its stone floor is cracked and uneven, worn by centuries of pilgrims, and part of it even slopes gently downhill in places. But whatever its physical state, its spiritual place is among the elite.

The cathedral is in the one-time capital city of England and is one of the country’s most important. Winchester was established as England’s capital by the Saxon King Alfred, centuries before London laid claim to the title.

Winchester nave. (© Bernadette Fallon)

Building began on the cathedral in 1079 by William the Conqueror seven years after his victory at Hastings. It was consecrated in 1093, a mere twenty years later. Stones from the old minster, the former church that had occupied part of the site, were used in its construction, creating a link between the old and established and the new and Norman. There were other links too, including its important patron saint, as we shall see.

The original church was built on the orders of King Cenwalh around 648 in the traditional shape of a cross. And while William’s eventual replacement followed the cruciform layout, the new structure dwarfed its predecessor. The cathedral’s new nave alone was longer than the whole of the former Saxon church.

Today the nave is a reworking of that original Romanesque style into the Perpendicular Gothic of the late 14th century, when the three-storey nave was completely remodelled into the current two-storey structure. Pointed arches stretch to the heavens and the vault soars majestically above, its exquisite detailing all achieved with stone.

However, you’ll still find parts of the original Romanesque building in the transepts. The Norman three-tier structure, with its lower-level arched arcade; the triforium in the middle; and the narrow windows of the clerestory at the top. Stand outside to get a true sense of the combination of architectural styles, the rounded Romanesque windows becoming pointed Gothic arches along the length of the building.

In fact, all of the major architectural periods are represented in Winchester Cathedral, from the early Anglo-Norman crypt to the Late Gothic of the presbytery aisles. And as well as linking different architectural styles through the ages, the building also carries reminders of its Saxon past and Winchester’s royal connection as the seat of kings. Mortuary chests around the walls of the presbytery, close to the high altar, contain the bones of Saxon kings and their successors, including the 7th-century King Cynegils, Egbert, the first king of the English, Ethelwulf, the father of King Alfred the Great, Canute, King of England, Denmark and Norway, and the early bishops of Winchester.

The bones came from the original Saxon cathedral and were moved to the new building in the early 1100s, though not in any great order. Bones were jumbled together in the crypt under the presbytery and later brought up above ground in the early 1500s. The parliamentarians threw all the bones away during a raid on the cathedral during the Civil War, but many were rescued and returned to the mortuary boxes. By then it was anyone’s guess which bones were which.

Curious facts: the saint who made it rain

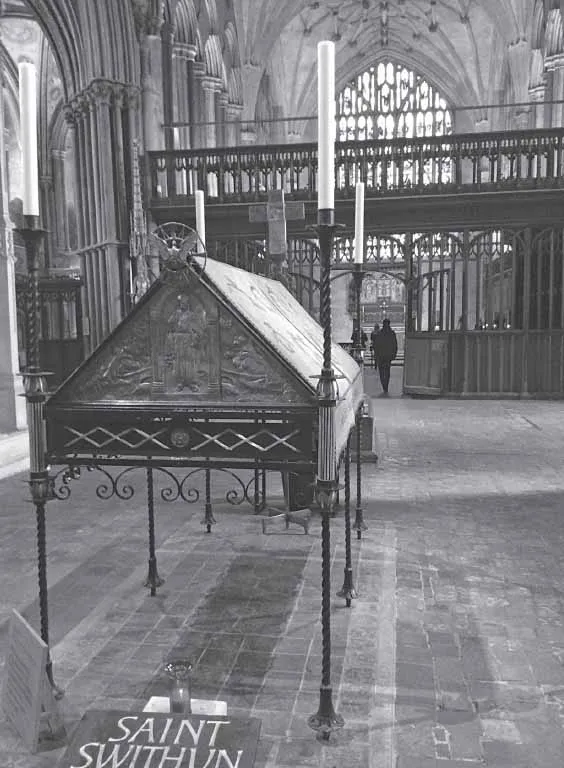

The other famous link between past and present is the cathedral’s original patron saint who was enshrined in the heart of the new cathedral. Once the Normans had finished their magnificent building, they reverently placed the silver chest containing the bones of the Saxon St Swithun in the greatest place of honour, the high altar.

Swithun was Bishop of Winchester from 852 to 863, advisor to King Alfred’s father Aethelwulf, and most likely a tutor to the young King Alfred himself. He performed many miracles during his life – including restoring a broken set of eggs back to their unbroken state – and the miracles continued after his death. Following his wishes, he was buried outside the west door of Winchester’s Saxon cathedral but was later moved inside so pilgrims could visit his relics in a decorated silver chest.

Swithun didn’t like it. Legend has it that it rained for forty days and nights after the move because of the saint’s displeasure. Which gave rise to the popular story that if it rains on St Swithun’s Day, 15 July, it will continue to rain for forty days after. And this – if you are familiar with English weather – is sometimes quite likely:

St Swithun’s day if thou dost rain

For forty days it will remain

St Swithun’s day if thou be fair

For forty days ‘twill rain nae mare

St Swithun’s memorial. (© Bernadette Fallon)

The high altar in the new cathedral might be a sufficiently reverent place for the patron saint’s relics, but it wasn’t the most practical location for pilgrims to access. One of Winchester’s early – and most important – bishops, Henry of Blois, had a solution. Inspired by a similar structure he had seen in St Peter’s in Rome, he built a 3m tunnel through which pilgrims could crawl under the shrine to get close to the saint, lighting their way with a lit taper.

You can still see where Swithun’s tunnel began in the east end of the cathedral. And a flight of steps from the north transept marks the pilgrims’ way up to the shrine, leading to a striking ‘carpet’ of ceramic tiles, featuring over sixty different designs. These were laid in the 1200s and today are a mix of the 13th-century originals and reproductions. So now, not only are you following the same route as the early pilgrims, you are also stepping on some of the tiles they walked on. Overall, this is the largest surviving area of tiles from this period.

Today you don’t need to crawl through a tunnel to pay your respects to Swithun. A metal frame with candle holders at each corner is a modern memorial to the saint and was made to mark the 1,100th anniversary of his death. Like so many other medieval saints of the time, his relics did not survive the destruction of the Reformation, when his shrine was demolished.

Demolished, but not completely lost, however. While the shrine was broken up, pieces of it were used as building materials elsewhere in the cathedral and, to date, over twenty pieces have been re-discovered.

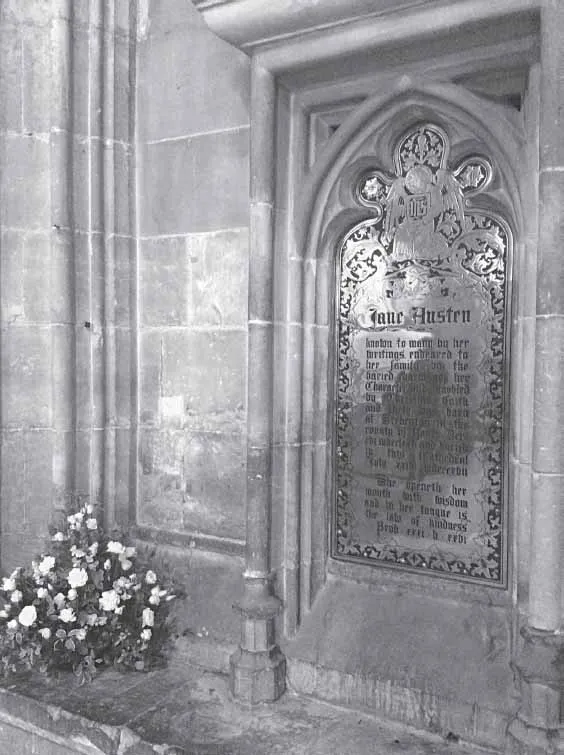

Don’t miss: the writer in the nave

One of the most famous and visited graves in the cathedral is in the nave. In May 1817, the author Jane Austen, suffering from illness, came to Winchester with her sister Cassandra to consult a doctor. They took lodgings near the cathedral on College Street. Her illness went undiagnosed and sadly Jane died here on 18 July. Though her illness was not even named in medical circles until the 1830s, judging by her symptoms it appears that she may have had Addison’s Disease, a rare disorder of the adrenal glands.

Her tomb is marked by a stone in the floor of the nave, placed there by her brother Henry. Paying glowing tribute to the ‘benevolence of her heart, the sweetness of her temper and the extraordinary endowments of her mind’, there is no mention of her writing. Penning novels wasn’t a seemly occupation for a woman in the early 19th century and Jane was not yet as famous as she would go on to become.

Jane Austen memorial. (© Bernadette Fallon)

Fifty years later her nephew, James Edward Austen-Leigh, had a brass plaque erected on a nearby wall, which acknowledges her life as an author in its opening words, ‘Known to many by her writings.’ Fittingly, he paid for the memorial with the profits of his book A Memoir of Jane Austen published in 1869 and reprinted as a second edition, with some of her previously unseen writing, in 1871.

But it wasn’t until 1900 that a more worthy tribute to Jane Austen the writer was installed, paid for by public subscription. Her stained-glass window by the esteemed Charles Kempe sits directly above her memorial plaque – though it does need a bit of interpretation. St Augustine is at the top, a play on her name – the abbreviated form of Augustine is Austin. Beneath is King David – who is linked to the psalms – and St John – who wrote the gospel – and the remaining figures are the sons of the Korah, who wrote some of the most beautiful psalms in the Bible. Jane herself makes an appearance in the Latin inscription that reads, translated, ‘Remember in the Lord Jane Austen who died July 18th A.D. 1817’.

This is not her original resting place, however. One hundred and twenty years after her burial, Winchester cathedral installed its first central heating system and Jane had to be moved six inches to the north to make way for the pipe running through the nave.

Who else is buried in the cathedral?

It’s fitting that the two bishops buried in the nave were the two men who did so much to remodel it. Work here was started by Bishop Edington between 1346 and 1366. As well as a bishop, he was also treasurer to King Edward III, chancellor of England and the first prelate of the Order of the Garter, the medieval group of honourable knights set up by King Edward III, inspired by the tales of King Arthur and the knights of the round table. The bishop’s alabaster effigy in his chantry chapel is one of the cathedral’s finest medieval sculptures.

Bishop Edington’s work was continued on a grand scale by his successor Bishop Wykeham, who completely remodelled the Norman nave into the soaring Gothic structure we see today. Wykeham lies in a magnificent chantry chapel, its location specially picked out by the bishop before his death. As a young boy, William heard mass said by his favourite monk, Richard Pekis, at an altar in the aisle. As Bishop of Winchester, he had his chantry chapel built on the spot where he had once stood and listened. Today it is cared for by Winchester College and New College Oxford, both of which he founded.

Don’t miss: the chantry chapels

Throughout the cathedral many chantry chapels have survived and you’ll find several of the most important in the retrochoir. The chapel of Bishop Stephen Gardiner is something of an anomaly, however, as chantries had in fact been forbidden by law by the time that Gardiner died in 1555.

He was an important man in the court of King Henry VIII, the king’s loyal advisor and appointed Bishop of Winchester for his services, the last Roman Catholic to hold the role. But Henry’s son, Edward VI, later had Gardiner imprisoned for refusing to enforce Protestant doctrine. He was released when the Catholic Queen Mary came to the throne, appointed Lord Chancellor and reinstated as Bishop of Winchester. In 1554, he conducted the marriage of Mary to Prince Philip of Spain in the cathedral.

William Waynflete, bishop from 1447 to 1486, was another very powerful and influential man, being also headmaster of Winchester College, Master and Provost at Eton, founder of Magdalen College Oxford, and Lord Chancellor of England. The intricate filigree carving around the outside of his chapel is particularly beautiful – look out for the snail carved in among the trailing roses.

And the royal roll-call continues. Cardinal Henry Beaufort, Bishop of Winchester from 1405 to 1447, was half-brother to King Henry IV, uncle to Henry V, great-uncle to Henry VI and three times Lord Chancellor of England. One of the richest men in the country, he left part of his fortune to the cathedral, which was used to build a new shrine for St Swithun and the wonderfully ornate great screen behind the high altar. It’s thought he may have been involved in the trial of Joan of Arc, whose statue you will find nearby, outside the Lady Chapel, standing on a piece o...