![]()

BLOODY OMAHA

The most deadly and intense battle of the D-Day invasion landings on 6th June 1944 was that fought on the five-milelong stretch of beach called Omaha by the Allied planners of the assault. It was the largest of the five landing beaches and the most difficult and dangerous to attack because of the high bluffs overlooking virtually the entirety of the beach and the nature of the enemy defences along most of their length. The task of taking Omaha and Utah beaches went to the Americans.

The Germans had carefully designed and built gun emplacements, observation posts, pillboxes and other hardened facilities on the clifftops, most of them connected by a series of trenches to ease the movement of their personnel between the facilities.

General Omar Bradley was leading the troops of the American 1st Army in the attack on the enemy forces at Omaha, which was set to begin at 0630. The Allied planners had intended for the American infantry troops to hit the beach in company with twenty-nine amphibious Sherman “swimming tanks” (DDs), which would have given the troops substantial fire power against the defending forces. Unfortunately, the Shermans were released from their landing craft much too far away from the beach. The swell on the sea at their release point was too heavy that far out and all but two of the tanks were swamped with water almost as soon as they left the landing craft. They began to sink as soon as they were released; the landing craft personnel could do nothing to help the crews of the Shermans and most of them drowned and the troops on the beach never received the armoured protection they were expecting.

In addition to these problems, the unpredicted strong winds and tides drove a number of the landing craft off line, adding to the extreme chaos among the Allied troops on the beach.

Omaha was heavily defended by German machine-guns and other gun emplacements which inflicted many hundreds of casualties among the Americans there. The only hope of success and survival for most of them lay in somehow managing to cross the strip of sand from the surf to the seawall, a sprint that for many was deadly. As General George Arthur Taylor, Commander of the 16th Infantry Regiment on Omaha said to those who remained from his unit, huddled there, exhausted, shell-shocked and pinned down along the seawall, “There are two kinds of people staying on this beach: those who are dead and those who are going to die. Now let’s get the hell out of here.”

The main Allied objective at Omaha was to secure a beachhead five miles deep between Port-en-Bessin and the Vire River, that would link up with the British forces that were landing further east, and reaching to Isigny to the west and link with the U.S. VII Corps landing at Utah beach.

The Allied D-Day planners assigned code-names to each of the five invasion beaches along the Normandy coast of France. From the west near St Martin de Varreville, there was UTAH, then OMAHA near St Laurent, then GOLD at Arromanches, JUNO near Ver sur Mer, and SWORD near Colleville sur Orne.

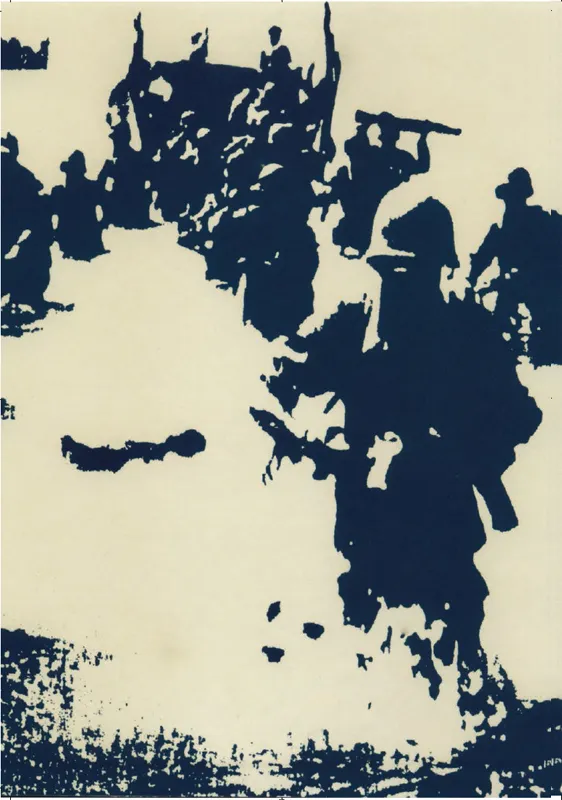

U.S. Troops landing at Omaha Beach on D-Day.

The strategy of the German defenders was to defeat any seaborne assault at the shore line. They were deployed at strongpoints all along the coast, detailed to defend a thirty-three-mile front. They were comprised of the 12,000 men of the 352nd Infantry Division, 6,800 of whom were experienced combat soldiers.

Responsibility for the sea transport of the American troops going to Omaha, the mine-sweeping, and a naval bombardment, fell to the U.S. Navy and Coast Guard who were ably assisted by the British, Canadian and Free French navies. One of the first actions on Omaha was that of the largely inexperienced 29th Infantry Division together with nine companies of U.S. Army Rangers who were meant to have landed down the beach a few miles at Pointe du Hoc, but instead were landed at Omaha. It was this combined outfit that was then sent in to attack the western half of the beach. The eastern half was assigned to the battle-experienced 1st Infantry Division, also known as “the big red one.” The planning called for the elements of the first wave of attackers—the tanks, combat engineer forces, and infantry—to destroy as much of the coastal defences as they could, in order to lessen the problems and danger to be faced by the following waves from the larger ships of the Allied armada.

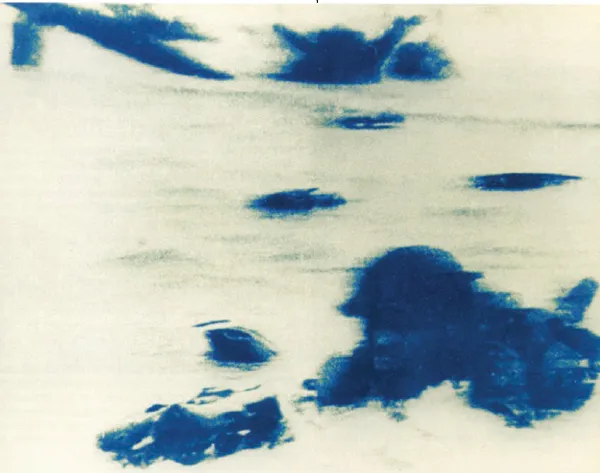

One of the American soldiers in the surf at Omaha on D-Day was Ed Regan, a young Pennsylvanian who happened to be caught on camera by the war photographer Robert Capa early that June morning in 1944;

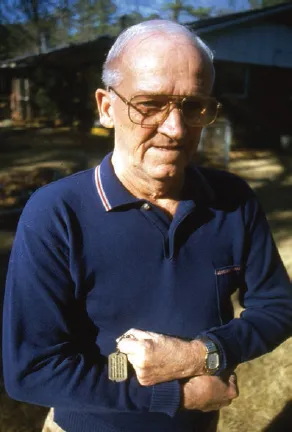

Ed grips his dog-tag souvenir of that grim experience—fifty years later.

For the Americans landing at Omaha, carrying out their plan of attack proved far more difficult than had been imagined back in the safe confines of the English south coast. Weather-related considerations and navigational problems led to the bulk of the landing craft missing their landing targets through much of the day. The strength of the enemy defences, particularly at Omaha, had been underestimated by the Allied planners and the casualties inflicted on the landing troops by the German defenders were certainly heavier than had been expected. The problem for the landing engineers as they struggled to try and clear the thousands of beach obstacles was massive. They had to do their work under heavy gun fire from the Germans in the hillside and hilltop positions. So heavy and intense were the casualties suffered by the American assault troops that their effectiveness in clearing the well-defended exits off the beach, which in turn created delays and additional problems. It took most of the long day for several small pockets of American survivors who somehow were able to launch makeshift assaults up the heavilyfortified bluffs and neutralize those enemy positions to a limited extent. Their progress was actually limited to just two pathways through the defences, but they later led to the elimination of additional enemy defences further inland. As they slowly advanced it became clear to the Americans that the defensive arrangements of the Germans, together with their evident lack of any substantial defence in depth, meant that the enemy plan was, if possible and at all costs, to simply stop the invaders on the beaches.

Treating a wounded American soldier on the beach at Omaha;

Five companies of German coastal defence infantry were distributed among fifteen strongpoints known as Widerstandsnester or “resistance nests” which were identified numerically from east to west, WN-60 through WN-74. These strongpoints were mainly located near the draws in the bluffs and were well protected with barbed wire and minefields. An intricate network of tunnels and trenches had been established connecting the various strongpoint facilities, which were also defended by a significant number of lighter weapons—rifles and machine-guns, as well as about sixty light artillery pieces. The Omaha Beach area was further protected by eight large-gun casemates and a further four open gun positions. Machine-guns and light weapons were housed in a system of about thirty-five pillboxes and the beach was also targeted by eighteen anti-tank guns. German defensive coverage of the spaces between the strongpoints was relatively light. There was a rather minimal layout of trenches and rifle pits, as well as some eighty-five emplacements with machine-guns. Rommel had seen to it that there were no holes or blank spots anywhere along the large and lengthy beach. His arrangement of weaponry had enabled efficient flanking fire employment to be laid down anywhere on it.

From Omaha Beachhead, a September 1945 publication of the United States War Department: “The assault on Omaha Beach had succeeded, but the going had been harder than expected. Penetrations made in the morning by relatively weak assault groups had lacked the force to carry far inland.

Shock and awe on Omaha in the early morning of D-Day.

Delay in reducing the strongpoints at the draws had slowed landings of reinforcements, artillery and supplies. Stubborn enemy resistance, both at strongpoints and inland, had held the advance to a strip of ground hardly more than a mile-and-a-half deep in the Colleville area, and considerably less than that west of St-Laurent. Barely large enough to be called a foothold, this strip was well inside the planned beachhead maintenance area. Behind U.S. forward positions, cut-off enemy groups were still resisting. The whole landing area continued under enemy artillery fire from inland.

“Infantry assault troops had been landed, despite all difficulties, on the scale intended; most of the elements of five regiments were ashore by dark. With respect to artillery, vehicles and supplies of all sorts, schedules were far behind. Little more than 100 tons had been got ashore instead of the 2,400 tons planned for D-Day. The ammunition supply situation was critical and would have been even worse except for the fact that 90 out of 110 preloaded DUKWs in Force ‘O’ had made the shore successfully. Only the first steps had been taken to organize the beach for handling the expected volume of traffic, and it was obvious that further delay in unloadings would be inevitable.

“Unit records for D-Day are necessarily incomplete or fragmentary, and losses in men and materiel cannot be established in accurate detail. First estimates of casualties were high, with an inflated percentage of ‘missing’ as a result of the number of assault sections which were separated from their companies, sometimes for two or three days. On the basis of later, corrected returns, casualties for V Corps were in the neighbourhood of 3,000 killed, wounded and missing. The two assaulting regimental combat teams (16th and 116th) lost about 1,000 men each. The highest proportionate losses were taken by units which landed in the first few hours, including engineers, tank troops, and artillery.

“Whether by swamping at sea or by action at the beach, materiel losses were considerable, including twenty-six artillery pieces and over fifty tanks. No satisfactory overall figures are available for vehicles and supplies; on unit, the 4042nd Quartermaster Truck Company, got ashore only thirteen out of thirtyfive trucks (2 ½...