- 176 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

"Altogether, a very detailed year-by-year account of escort development for anti-submarine work from the period between the wars to post World War II." —The Nautical Magazine

Winston Churchill famously claimed that the submarine war in the Atlantic was the only campaign of the Second World War that really frightened him. If the lifeline to North America had been cut, Britain would never have survived; there could have been no build-up of US and Commonwealth forces, no D-Day landings, and no victory in western Europe. Furthermore, the battle raged from the first day of the war until the final German surrender, making it the longest and arguably hardest-fought campaign of the whole war.

The ships, technology and tactics employed by the Allies form the subject of this book. Beginning with the lessons apparently learned from the First World War, the author outlines inter-war developments in technology and training, and describes the later preparations for the second global conflict. When the war came the balance of advantage was to see-saw between U-boats and escorts, with new weapons and sensors introduced at a rapid rate. For the defending navies, the prime requirement was numbers, and the most pressing problem was to improve capability without sacrificing simplicity and speed of construction. The author analyses the resulting designs of sloops, frigates, corvettes and destroyer escorts and attempts to determine their relative effectiveness.

" Atlantic Escorts has flowed from the pen of a master who has written so many fine books about the history of ship construction. It is a small masterpiece." —Warship International Fleet Review

Winston Churchill famously claimed that the submarine war in the Atlantic was the only campaign of the Second World War that really frightened him. If the lifeline to North America had been cut, Britain would never have survived; there could have been no build-up of US and Commonwealth forces, no D-Day landings, and no victory in western Europe. Furthermore, the battle raged from the first day of the war until the final German surrender, making it the longest and arguably hardest-fought campaign of the whole war.

The ships, technology and tactics employed by the Allies form the subject of this book. Beginning with the lessons apparently learned from the First World War, the author outlines inter-war developments in technology and training, and describes the later preparations for the second global conflict. When the war came the balance of advantage was to see-saw between U-boats and escorts, with new weapons and sensors introduced at a rapid rate. For the defending navies, the prime requirement was numbers, and the most pressing problem was to improve capability without sacrificing simplicity and speed of construction. The author analyses the resulting designs of sloops, frigates, corvettes and destroyer escorts and attempts to determine their relative effectiveness.

" Atlantic Escorts has flowed from the pen of a master who has written so many fine books about the history of ship construction. It is a small masterpiece." —Warship International Fleet Review

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Atlantic Escorts by David K. Brown in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Military & Maritime History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1 | Between the Wars |

The Lessons of World War I

There does not seem to have been any high level discussion paper on the lessons of the submarine war of 1914–18. In part, this may have been a result of excessive secrecy, particularly with regard to intelligence, direction-finding, etc.1 The notes that follow are based on hindsight.

The first lesson was that the UK was very close to defeat in 1917 and remained vulnerable to submarine attack. The German U-boat force had three main objectives: to weaken the Grand Fleet by attrition, so that the High Seas Fleet could fight on level terms; to defeat the UK by starvation; and to prevent the US Army from reaching France.2

The U-boats failed in all three. Attempts to attack the Grand Fleet and US army transports had negligible results. At the end of 1916 a German report estimated that sinking 600,000 tons of merchant shipping per month would bring victory within five months. The losses in 1917 were terrible but monthly sinkings only twice exceeded 600,000 tons. Attacks on merchant shipping came close to success but were defeated mainly by the introduction of convoy. Even so, large numbers of escorts were needed. ‘Hunting’ without precise location was of no value.

The enormous building programme of merchant ships (and escorts) in the USA was a major contributory factor. This was only partially offset by the building of U-boats, which by 1918 had steadied at about eight boats per month. There were concerted efforts to increase the building rate, but with little success. It is probable that the bottleneck lay in the supply of auxiliaries such as pumps, periscopes, etc., whilst training of crews – commanding officers in particular – remained a problem. However, defence analysts in the late thirties would have been wise to expect Germany to achieve at least an equal rate of completion of submarines.

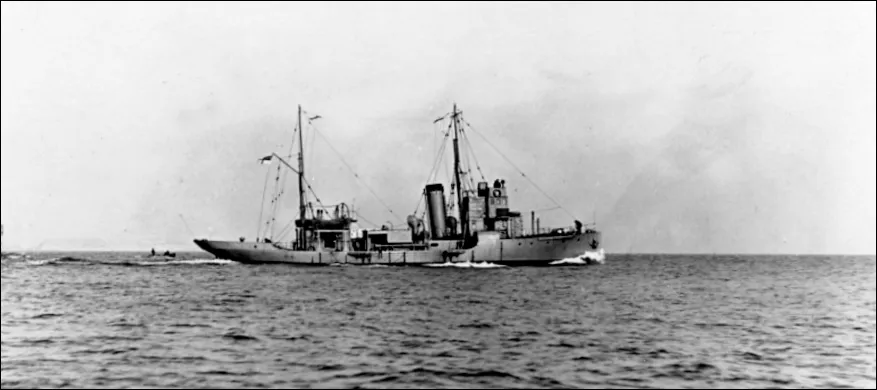

Cachalot, a World War I escort based on a whale catcher. She was used in numerous trials of early asdic development.

Tactically, the increasing number of night, surface attacks in 1918 should have been noted, though these were solo attacks and not the wolf pack attacks of the later war. It should also have been recognised that even in 1917 U-boats could reach the east coast of the USA from German bases. The lengthy building time for U-cruisers, together with their relative lack of success, was misread and most big navies began to build ‘monster’ submarines.3

After the war there seems to have been a comfortable feeling that submarines had been defeated without the use of asdic, while whispers of this new sensor suggested that submarines had lost their cloak of invisibility. There were attempts to agree an international ban on submarines but they were never likely to succeed. Indeed, the RN submarine-building programme for the Far East suggests that it was recognised that a ban was never likely to be agreed. There was agreement that any submarine attacking a merchant ship would obey Prize Rules on safety of the crew, etc. but it is likely that there was little confidence that this would be maintained.

The Threat

In the 1920s there was little or no submarine threat to British merchant shipping. The USA had been ruled out as a potential enemy in the early years of the century and though the build up of French bombers and submarines was a matter of concern, the Entente Cordiale still held. Japan was seen as a potential enemy and was building a considerable number of fleet submarines but it was believed (correctly) that Japanese doctrine saw these boats as of use against an enemy battle fleet rather than merchant shipping.

Under the Versailles Treaty, Germany was forbidden to build or own submarines. However, as early as 1922, a design bureau, N V Ingenieurskantoor voor Scheepsbouw (IvS), was set up at The Hague to preserve German expertise by designing submarines for other nations. In 1926 they received an order for two boats from Turkey and trials were carried out in 1928 with German personnel. Also in 1928 an order for three boats was received from Finland. These went on trials in 1930, again with German crews. In 1934 another Finnish boat, Vessiko, the prototype of the later Type IIA of the German Navy, went on trials with a mixed Finnish and German crew. Later she was used to train German submarine crews. The Admiralty was aware of these developments4 but saw them as not a serious threat and even, perhaps, a bulwark against the Soviet Union.

On coming to power, Hitler’s Nazi Party renounced the treaty restrictions of Versailles and began to produce material for a submarine fleet. Construction of the Type IA began in 1935; this type was based on a boat ordered by Spain as E1 but sold to Turkey before completion. The Type IA seems to have been unsuccessful, as only two were built. They were followed by the 250-ton Type IIA, which completed only four months after they were laid down, as so much preparatory work had been done. Their main function was crew training but the British Admiralty saw them as designed for Baltic operations against the Soviet Union.

The Anglo-German Treaty of December 1935 limited the tonnage of the German submarine fleet to 45 per cent of that of the RN but with an escalator clause permitting an increase to equality in the event of a threat from a third party, after discussion. This clause was invoked in December 1938 without discussion.

Budgets

During the 1920s and early 30s, expenditure on the Navy was very tight. Battleship-building was forbidden under the Washington Treaty, extended by the London Treaty to 1937, but available building funds went mainly on cruisers and destroyers. A very few sloops were built as prototype minesweepers and escorts that could be used in peacetime as colonial policemen. It should be remembered that the Army and the RAF were, if anything, even worse funded than the Navy.5

The development of asdic, discussed later, gave priority to research and prototype units rather than an early production fit. Improvements followed each other rapidly and with no serious threat this may be seen as a wise policy. It did result in the A class destroyers and a few sloops completing ‘for, but not with, asdic’, although this was remedied before the war. Some effort was put into the development of an ahead-throwing weapon (see photo of Torrid) but this was abandoned because asdic technology was not then accurate enough to direct such a weapon without major work. Resources were scarce and needed for work seen as higher priority.

Torrid was used for trials of an ahead-throwing A/S weapon in the early 1930s. Mounted in A-position, it fired a stick bomb up to 800 yards. Target location with the asdics of the day was not good enough and effort was not available to cure the problems.

Tactics and Training

The flotilla at Portland developed the tactical use of asdic and in so doing exposed most of its weaknesses. In particular, the bending of the asdic beam by layers of water of different density was known, mainly from trials in the Mediterranean, though the full effect was probably not appreciated until the Spanish Civil War and the Neutrality patrols.

Exercises with submerged submarines were not, with rare exceptions, permitted after dark, though a few night exercises took place using surfaced submarines – surely more dangerous? Hence the value of night surface attack by submarines was known to some extent.6 There was a lack of awareness of the extent to which night surface attack was employed in the last year of World War I. Detection of a low-lying submarine by eye on a dark night is very difficult, a problem only solved when effective radar sets became available. Overall, those involved in ASW had developed effective weapon systems controlled by asdic, and tactics to employ these systems. However, as Franklin has shown, ASW officers did not figure in the higher ranks of the Admiralty, who were not fully aware of either the capability of ASW forces or their limitations.

Early 1930s

A major review of ASW was carried out in 1932,7 when there was still no direct submarine threat to the UK. The potential threat was already seen as Germany, even though she had no submarines at that date and it was envisaged that the lengthy voyage round the north of Scotland would mean few U-boats on station. These few could be countered by the older destroyers of the A–I classes and earlier destroyers, and by the few sloops. It was recognised that minesweeping and ASW had differing requirements, particularly as to draught, and the convoy sloop departed from the minesweeper design. It is, perhaps, ironic that the Halcyon class minesweeping sloops spent much of the war as ASW ships. The east coast was seen as the danger area and a number of countermeasures were put in hand. That area of operations lies outside the scope of this book but we shall look at it briefly for the sake of completeness.

Picotee. She is typical of the early Flower class, which were the only escorts which could be built in numbers in 1939. She mounts a four-barrelled machine gun in place of her pom-pom. (WSS)

The aircraft threat was recognised as serious on the east coast and led to the Hunt class with a very heavy AA armament; a number of older V&W class destroyers were also mo...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Glossary

- Introduction

- Chapter 1: Between the Wars

- Chapter 2: War, the First Phase: September 1939–April 1940

- Chapter 3: After the Fall of France: June 1940–March 1941

- Chapter 4: A Gleam of Light: April–December 1941

- Chapter 5: The Second Happy Time: January–June 1942

- Chapter 6: The Pendulum Swings: August 1942–May 1943

- Chapter 7: Pause, Counterattack and Victory: June 1943–May 1945

- Chapter 8: Some Technical Aspects of the Battle

- Chapter 9: Production: Building the Ships to Win the Battle

- Chapter 10: Evaluation: How Good Were They?

- Postscript: The Fast Submarine

- Appendix I: Diving Depth and Pressure Hull Strength

- Appendix II: Fitting of 6pdr Guns

- Appendix III: Loss of Destroyers in Bad Weather

- Appendix IV: Asdic Sets

- Notes and References

- Bibliography