![]()

Captain Cook’s War, 1755–1762

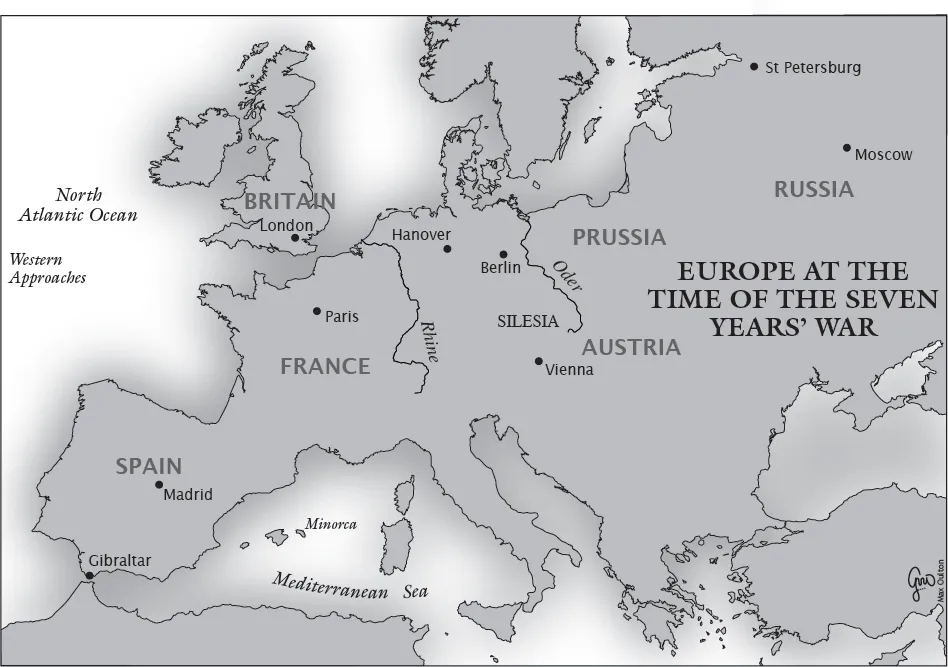

James Cook joined the Royal Navy in 1755, exchanging life as mate on a collier in the North Sea for life as an able seaman on a ship of the line. He did so just as the Seven Years’ War (or Captain Cook’s War, as I will call it), which had been simmering for some time, was beginning in earnest. The war would dictate the events in Cook’s life for the next few years. The principal protagonists, the major European nations, had been lining up to begin another in the series of wars that marked the eighteenth century and which regularly interrupted the short periods of peace. The previous war, the War of Austrian Succession had finished in 1748 and the Treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle that formally ended that war had resolved little. For many of the nations involved, the treaty only represented a temporary truce. In this way, the Seven Years’ War may be viewed as a continuation of the earlier war.

Fighting took place beyond Europe, on other continents, and some commentators in the late twentieth century began to portray this war as the first global conflict. The war is actually known by several different names. The overall name by which it is known in Britain and France is the Seven Years’ War (lasting there from 1756 to 1762). However, the duration of the war varied, depending on the location and, in North America, where fighting lasted from 1754 to 1760, the war is known as the French and Indian War. The war in Central Europe is known by some as the Third Silesian War, and for part of the war in India the term Third Carnatic War is used. Given William Pitt’s role in directing the British effort, some British historians referred to it as Pitt’s War. Captain Cook’s War is therefore another in a long line of appellations.

France and Britain were invariably on opposite sides during the eighteenth-century wars and, similarly, Austria and Prussia usually opposed each other. King Frederick II of Prussia had gained the rich province of Silesia in 1748 and Empress Maria Theresa of Austria had agreed peace terms only in order to rebuild her army and to form new alliances. Nations often formed alliances with different partners and so Austria – which had been allied with Britain before 1748 – this time formed a new alliance with France, and a pact was signed at Versailles in May 1756. Prussia was at odds with most of its neighbours and Russia, Sweden and Saxony soon sided with Austria and France against Prussia.

George II of Britain was still Elector of Hanover and retained strong interests there, so Britain signed the Convention of Westminster with Prussia in January 1756 – in anticipation of the Austrian move – believing that Prussia would assist in the protection of Hanover. The French-Austrian-Russian alliance might have much larger numbers of fighting men but Britain had the best navy and Prussia had the most effective army and commanders. This agreement allowed Britain to concentrate on control of the seas and on land actions in North America and India, leaving Prussia to handle things in Continental Europe. The war began formally in Europe in May 1756 when Britain and France declared war on each other. Frederick of Prussia then invaded Saxony in August, thus starting the war in Central Europe.

The other spark for war came from the rivalry between Britain and France over land and new territory, especially in North America and India. Skirmishes and small actions had been taking place in these locations for some time before 1756. In North America, events began in 1754 and George Washington, the future first President of the United States, was at the centre of things. The French had entered the Ohio valley and Washington was dispatched from Virginia to investigate. Relations deteriorated, fighting broke out and soon full-scale warfare began. Britain dispatched troops under Edward Braddock to Fort Duquesne (Pittsburg) in 1755 but they were roundly beaten. The much smaller population of French Canada could not sustain an army to fight the superior numbers assembled by the British and, though the French continued to win further encounters over the next three years, they were never able to gain total victory. For their part, the British could afford to suffer those defeats before inflicting two significant blows at Louisbourg and Quebec that ended all French hopes.

India was the third theatre where fighting broke out as old rivalry between the British and French East India Companies escalated. Both sides had alliances with local Indian rulers and the ensuing battles often involved Indian troops fighting alongside Europeans.

In central Europe, Frederick II (or Frederick the Great, as he was often known), the King of Prussia, had invaded Silesia in 1740, the same year that he took power. The ensuing First Silesian War (174–), part of the War of the Austrian Succession, resulted in Prussia retaining the province. Austria attempted to recover Silesia in the Second Silesian War (174–), but Frederick was victorious again. In 1756, Austria, keen to recover Silesia, sided with France, even though they had been traditional enemies, and began conspiring against Prussia. Frederick, aware of developments, acted first by entering Saxony on 29 August. This was the first action in the Third Silesian War (175–2).

Russia, under Empress Elizabeth, entered the conflict on the side of Austria, and a series of inconclusive battles were fought over the next six years. Huge numbers of men were killed or wounded in these clashes. Each side won some encounters and then lost some, and territory was similarly gained and lost. Prussia’s army was able to survive even in the face of more numerous enemy because it was much better trained and organised. It also had, in Frederick, a leader of exceptional ability.

Frederick was helped by Ferdinand, Duke of Brunswick-Lüneburg, who assumed command of the allied Hanoverian army in November 1757 after that army’s defeat under the Duke of Cumberland at Hastenbeck. Ferdinand skilfully led his army against the French for the next four years, tying the French down so that they were unable to assist Austria against Prussia. The Austrian army was led by Leopold Josef, Graf Daun. He was a cautious general and let slip several opportunities where he could have pressed home an advantage that might have defeated Prussia. Prussia was also fortunate in that Austria rarely worked in unison with the Russian army, commanded by Count Pyotr Semyonovich Saltykov.

Britain originally declined to commit its forces on the Continent, where it depended on Prussia and Hanover to carry on the fight. It did, however, help fund the Prussian army and later committed some troops to help the Hanoverian army fight the French near the Rhine. Britain’s war aims, largely directed by William Pitt (see section ‘William Pitt and the Seven Years’ War’), were to control the seas and thereby destroy the French navy and merchant fleet. France would then be in no position to assist its colonies; Britain’s empire would grow and France would no longer be a rival. Britain’s situation was helped greatly by France concentrating its efforts in Europe to fight Prussia and Hanover.

Pitt was prepared to order naval attacks on selected French ports, which would irritate the French and cause them to retain troops in France that would otherwise have gone to fight on France’s eastern front. Attacks were made against Rochefort, St Malo and Cherbourg, though not with much success.

In other areas British sea power was one of the telling factors in the war. Despite being short of ships and experienced crews when the war began, Britain quickly built up its fleet and was soon able to use it to stifle French efforts. Anson, as first lord of the Admiralty began reorganising the Royal Navy. He promoted capable admirals such as Boscawen, Hawke and Saunders to counter the existing group of elderly and incapable ones. The seas around Britain were to be regarded as British territory, needing constant protection. Soon the British navy was larger than the French and Spanish combined.

Anson developed the idea of the Western Squadron operating in the Western Approaches to the English Channel and in the Bay of Biscay. The following quote is attributed to Anson from 1756:

Our colonies are so numerous and so extensive that to keep a naval force at each equal to the united force of France would be impracticable with double our Navy. The best defence therefore for our Colonies as well as our coasts is to have such a squadron always to the Westward as may in all probability either keep the French in port or give them battle with advantage if they come out.1

Fleets of British ships were soon patrolling off Brittany to effect a blockade of Brest, the major French port, while other British ships based at Gibraltar prevented French vessels leaving the Mediterranean. In this way French colonies were cut off from support and were at the mercy of the British forces able to attack them. The French government was mostly powerless to help and left its colonies to fend for themselves. The French attitude to Canada at the time was summed up by Voltaire: ‘You are perhaps aware that these two nations [France and England] are at war over a few acres of snow near Canada although they could buy up the whole of Canada with the money they are spending on the war.’2 France persuaded Spain, which until then had been neutral, to join the French side in 1761. This only served to widen the war and Britain quickly responded. In 1762 British forces attacked and captured the Spanish cities of Havana in Cuba and Manila in the Philippines.

In Europe the normal method of fighting major battles involved the two armies facing each other on an open expanse and then attacking with infantry, cavalry and artillery. The armies of Central Europe fought a whole series of battles along these lines but the results were indecisive as first one side won and then the other gained a temporary victory. Throughout the war the Prussians were greatly outnumbered and were attacked on two fronts by Russia and Austria, but their superior leadership – especially Frederick’s – ensured that they remained in the fight. Both sides lost such large numbers of men that a draw was inevitable.

In North America a more irregular form of warfare developed; this new method of fighting was a novel experience for the British, which they took time to come to terms with. Much of North America was still covered in forest, and open spaces where European-style battles could be fought were uncommon. Much of the fighting took place in wooded areas, rendering cavalry and artillery largely ineffective. The French Canadians and their Native American allies had perfected a form of guerrilla warfare and often harried and ambushed British forces, each time inflicting small-scale losses that accumulated over time. The British were unfamiliar with these conditions and continued to wear their traditional uniforms, which were unsuitable for the new type of warfare. Many battles involved besieging forts, which also required different tactics. The scale of operations was also very different in North America from that in Europe. Battles in Europe often involved armies with thirty thousand men or more on each side, while even at Quebec, one of the largest battles in North America, the armies only totalled about four and a half thousand men on each side. The battle at Quebec was the first fought in the European manner and the British were in their element there. The French Canadians opposite them were undisciplined and untrained to face enemy fire so, when the first fusillade devastated their lines, the survivors turned and ran.

James Cook’s experiences during the Seven Years’ War were quite varied. He was occasionally at the centre of things but more often he was involved in routine work away from the action. During the first two years of the war Cook was on HMS Eagle, which undertook patrols off the Irish coast, took part in the blockade of Brest and patrolled the Normandy and Brittany coasts to prevent invasion. Eagle often stopped and captured small vessels but it was only near the end of Cook’s time on the ship that Eagle was engaged in a major action, when a French Indiaman was attacked. Most of the time was spent sailing back and forth in cold and often stormy conditions, which took their toll on the ship and the crew. Despite the apparent lack of activity, the blockade of which Eagle was a part was a major contributing factor in the overall British victory.

Cook was promoted to master in 1757 and transferred onto HMS Solebay for a couple of months. The ship undertook an incident-free patrol from Leith to Shetland and back. Later that year Cook joined HMS Pembroke and, after a few more months of taking part in another blockade, sailed to North America. During 1758 and 1759 Cook was present at two of the most decisive battles of the war. He was largely an observer at the siege of Louisbourg in 1758 but played a significant part during the siege of Quebec the following year. Louisbourg introduced Cook to surveying and he became proficient so quickly that he was able to put his new skills into practice in the St Lawrence River near Quebec.

The French loss at Quebec was effectively the end of the war in North America, although the French held out until September 1760, when they eventually surrendered at Montreal. By then Cook was master on HMS Northumberland and based at Halifax, Nova Scotia. The war in Europe continued and the British could not afford to leave Canada unprotected so Cook and Northumberland were part of a squadron left to prevent the French from making an attempt to retake the country. It was a time of routine and boredom as Cook’s ship did not leave port for nearly two years before responding to a French attack that took place in mid-1762. In one of the last acts of the Seven Years’ War, a French force captured St John’s, the capital of Newfoundland; Cook was part of the British force that retook the island in September 1762. This marked Cook’s introduction to the island that became the centre of his activity for the next five years. Northumberland then crossed the Atlantic to find a Britain ready for peace.

Thus ended Captain Cook’s war. That he had survived was no mean feat. Death or injury such as loss of limb was common through naval battles, but many more men succumbed to scurvy and other diseases prevalent on Royal Navy ships of the time. Cook could even be said to have prospered during the war. Having started on the lowest rung, he had been promoted to emerge as a ship’s master, the senior warrant officer ranking. He had developed other abilities and his surveying skills had marked him out so that he was soon appointed to undertake a survey of the largely unknown coastline of Newfoundland. To complete matters, he married.

The war in Europe had also drawn to a weary close. Fighting had ended in Central Europe in November 1762 and the conflict there was formally concluded by the Treaty of Hubertusburg on 16 February 1763. Territorial boundaries remained as they had been in 1756, and Prussia retained Silesia. In Western Europe, William Pitt, who was responsible for much of the planning behind Britain’s success, had been forced from office and his successor, the Earl of Bute, wanted peace – as did the majority of the population. Peace negotiations began between Britain, France and Spain in late 1762 and a treaty was signed at Paris on 10 February 1763. Among the clauses were three that impinged on Cook in his future role:

IV. … His Most Christian Majesty cedes and guaranties to his said Britannick Majesty, in full right, Canada, with all its depend...