- 208 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

"Rose looks at every aspect of English naval power in the Medieval period . . . an excellent study of a somewhat neglected period of English naval history." —

History of War

We are accustomed to think of England in terms of Shakespeare's "precious stone set in a silver sea," safe behind its watery ramparts with its naval strength resisting all invaders. To the English of an earlier period from the 8th to the 11th centuries such a notion would have seemed ridiculous. The sea, rather than being a defensive wall, was a highway by which successive waves of invaders arrived, bringing destruction and fear in their wake.

Deploying a wide range of sources, this new book looks at how English kings after the Norman Conquest learnt to use the Navy of England—a term which at this time included all vessels whether Royal or private and no matter what their ostensible purpose—to increase the safety and prosperity of the kingdom. The design and building of ships and harbour facilities, the development of navigation, ship handling, and the world of the seaman are all described, while comparisons with the navies of England's closest neighbours, with particular focus on France and Scotland, are made, and notable battles including Damme, Dover, Sluys and La Rochelle included to explain the development of battle tactics and the use of arms during the period.

The author shows, in this lucid and enlightening narrative, how the unspoken aim of successive monarchs was to begin to build "the wall" of England, its naval defences, with a success which was to become so apparent in later centuries.

We are accustomed to think of England in terms of Shakespeare's "precious stone set in a silver sea," safe behind its watery ramparts with its naval strength resisting all invaders. To the English of an earlier period from the 8th to the 11th centuries such a notion would have seemed ridiculous. The sea, rather than being a defensive wall, was a highway by which successive waves of invaders arrived, bringing destruction and fear in their wake.

Deploying a wide range of sources, this new book looks at how English kings after the Norman Conquest learnt to use the Navy of England—a term which at this time included all vessels whether Royal or private and no matter what their ostensible purpose—to increase the safety and prosperity of the kingdom. The design and building of ships and harbour facilities, the development of navigation, ship handling, and the world of the seaman are all described, while comparisons with the navies of England's closest neighbours, with particular focus on France and Scotland, are made, and notable battles including Damme, Dover, Sluys and La Rochelle included to explain the development of battle tactics and the use of arms during the period.

The author shows, in this lucid and enlightening narrative, how the unspoken aim of successive monarchs was to begin to build "the wall" of England, its naval defences, with a success which was to become so apparent in later centuries.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access England's Medieval Navy, 1066–1509 by Susan Rose in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & European Medieval History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER 1

The Sources for Medieval Maritime History

SIR NICHOLAS HARRIS NICOLAS, writing in the first half of the nineteenth century in the Preface of his History of the Royal Navy, declared that ‘it is from the Chroniclers that the narratives of expeditions and sea fights have been derived’, but went on to explain how ‘all the details which afford accurate and complete information of Naval matters’ have been taken from royal writs and accounts.1 Any modern writer will be forced to follow much the same approach. For most of the period from 1066–1500 official legal and financial records are by far the most plentiful written documents. These were compiled by the clerks in the Chancery and Exchequer, the basic organs of royal government. It is not until the late fourteenth and fifteenth centuries that more personal and private documents can be found which give some limited impression of individual personalities. Another possible source, especially with regard to ship design, is visual material of various kinds including illustrations in manuscripts and town seals. There are also, of course, material survivals from the period which cast light on maritime history and the people who made their living from the sea. While excavated wrecks from our period in British waters are few and far between, and contain little in the way of surviving equipment or personal possessions, we can also learn from the layout of harbours and coastal towns and their fortifications. All these will be discussed below.

This picture comes from the margin of a manuscript. The vessels shown are probably intended to be cogs. The ferocity of sea warfare is conveyed, along with the fact that the taking of prisoners for ransom was seldom practised at sea, although usual in land battles.

(BRITISH LIBRARY)

Chronicles and narratives

Medieval England is in general well served by chroniclers, who often provide a careful and thoughtful narrative of events. While the earliest writers were churchmen, by the second half of the fourteenth century chronicles were also kept by laymen, most notably in the City of London, and had become in some cases more deliberately literary creations rather than mere annals. Chronicles dating from after the Conquest were usually in Latin, until either English or occasionally French became more common in the late fourteenth and fifteenth centuries. While most chroniclers have a reasonably good understanding of their own society and the way it was organised, a particular problem can be encountered when they are writing about maritime affairs. It is more or less impossible to know if any individual writer had any direct experience of the sea or had ever himself been on board a vessel, no matter what the circumstances. The details of sea fights tend to be glossed over in standard phrases with, not surprisingly, most emphasis laid on the result. There was also little acceptance of the modern belief that writers should not copy the works of their predecessors without acknowledgement. It was very easy for a standardised stereotypical account of a battle to become part of a chronicler’s ‘toolbox’, as it were, to be produced in the appropriate place when needed.

The account of the battle of Dover in 1217 between the French and the supporters of the young King Henry III in a contemporary verse biography of William the Marshal is dramatic, but says little of the way the two fleets were handled. The author lays more emphasis on statements like ‘When they captured a ship they [the English] did not fail to kill all they found aboard and threw them to the fishes leaving only one or two and occasionally three alive.’2 Describing the same event, Matthew Paris, the highly regarded chronicler based at St Albans Abbey, mentions the English fleet changing course in response to a wind shift which was to their advantage, but says little else about the course of the battle.3 After describing a conventional boarding action, he was clearly most interested in the grisly execution of Eustace the Monk, a Flemish sea rover who became something of a folk hero. Neither writer was present at the battle and it is hard to discover whether they had access to any participants, or were merely relying on common reports of the encounter.

This is an early picture of a sea battle from a copy of De Re Militaris, a Latin handbook of good practice for commanders that has a short section on naval warfare. The weapons used in war at sea are shown, including longbows, crossbows and pikes. There is little sign of tactics particular to a sea battle.

(SOURCE?)

In the few cases where it is clear that the writer was well versed in maritime matters and was present at a sea battle, more reliable detailed information can sometimes be included. The life of a Spanish nobleman adventurer, Dom Pero Niño, by his standard bearer, Gutierre Diaz de Gamez, known as El Victorial includes valuable information about the tactics used at sea by experienced commanders.4 The author had much to say about galley warfare in the Mediterranean where he had sailed with his master. In 1406, Niño was supporting the French Crown in the Channel and the waters off Cornwall. One story concerns an encounter in the Channel not far from Calais between the Spanish galleys assisted by some French balingers (small swift ships equipped with both oars and sails) and an English fleet of sailing ships. The author explains how the galley crews were given courage by a ration of wine handed out before the battle commenced. He lays emphasis on the wind direction and its strength, and how a fire ship was allowed to drift towards the enemy at the beginning of the battle. Finally, he describes how one of the leading galleys was saved from capture by the English by a French balinger suddenly altering course in the midst of the fray and ramming an English ship.5 This incident does not appear in contemporary English chronicles and may perhaps over-emphasise the skills and bravery of Niño and his galleymen, but it also casts light on fighting at sea, which is often dismissed as little more than hand-to-hand fighting on the decks of vessels grappled together.

Despite these problems, however, chronicles are invaluable for their accounts of events. It must be remembered that not only those originating in England itself can be helpful but also those written in France, the Low Countries, and elsewhere. The accounts of campaigns and battles in chapter 7 will make clear how much information about English maritime affairs is found in narrative sources from a wide range of European countries, as well as from England itself.

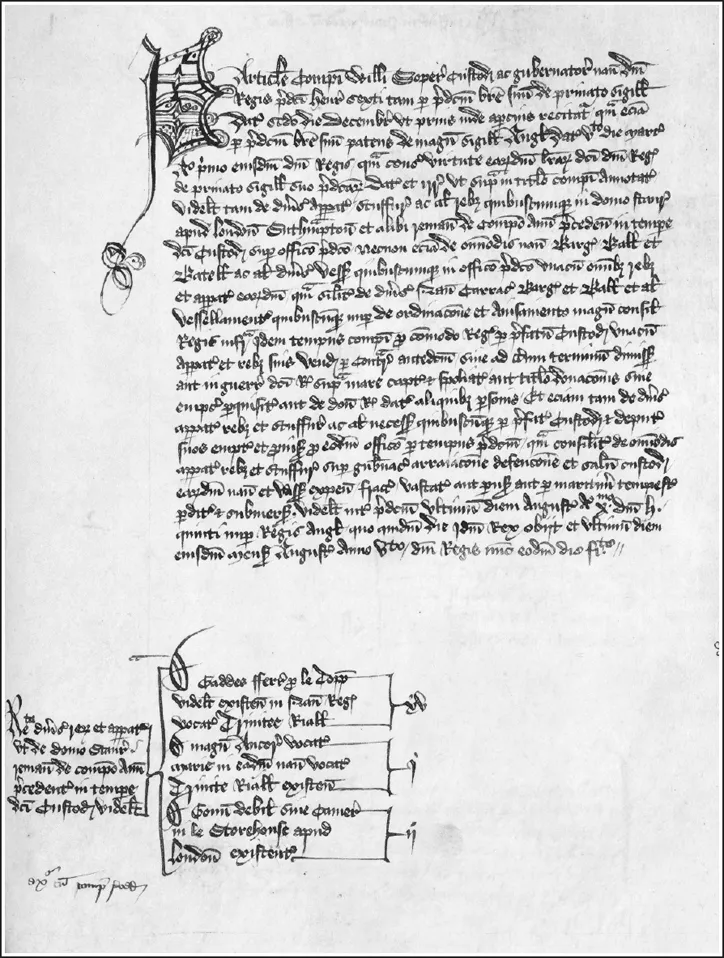

This is a short extract from a naval account from around 1350 in The National Archives and gives some idea of the usual layout. All sums of money on the right of the image are in Roman figures and refer to ‘money of account’ pounds, l (libri), s (solidi or shillings), and d (denarii or pence). This bore little relation to the actual coinage in people’s pockets. The title ‘Recepta’ (receipts) is in the right-hand margin.

(THE NATIONAL ARCHIVES)

Royal documents: accounts, writs and legal documents

The earliest payments to shipmasters are recorded among the final section, the so-called ‘foreign accounts’, of the Pipe Rolls, which were kept separate from the bulk of the rolls which relate to the dues and fees of county sheriffs. The purpose of these rolls was to record the accounts of sheriffs and all other officials who received or expended royal funds. The rolls constitute the main audited accounts of the Exchequer and run in a continuous series from 2 Henry II (December 1155/December 1156) till 1810. By 1358, in the reign of Edward III, an official with the title of Clerk of the King’s Ships existed, with separate audited accounts in this part of the Pipe Rolls. These rolls had, however, finally become so bulky and awkward to handle that from 42 Edward III (1368/9) certain accounts were enrolled on separate Rolls of Foreign Accounts. The Accounts of the Clerks of the King’s Ships were included in this group and can be found on the Foreign Account Rolls from 1371 till 1452, when no new appointments were made to this office till the reign of Henry VII.6 Between 1233 and 1426/7 the Pipe Rolls also contain a few scattered ‘special’ accounts for the building of galleys and other ships for the Crown.

This the opening page of the Account Book of William Soper, Clerk of the King’s Ships 1421–27. It sets out the basis on which he held the office and then lists equipment in store belonging to a royal ship called the Trinity Royal, including an anchor called Marie.

(© NATIONAL MARITIME MUSEUM, GREENWICH, LONDON)

A great deal of very useful financial and other material concerning the use made of ships by the Crown can also be found among what is known at The National Archives as Exchequer Accounts Various.7 This is a vast collection of accounts, writs, indentures, and other documents on many topics, but a great deal is usefully indexed under the heading of Army Navy and Ordnance, beginning with items from the reign of John. Many of the documents are particulars of account: that is, the accounts kept by an individual officer concerning his income and expenditure which were delivered to the Exchequer, often at the end of a term of office, and used by the Exchequer clerks to make up the audited accounts. Their survival is much more patchy and sporadic than that of the audited rolls; many officials probably took them back to their homes once the tedious auditing process had been completed. The particulars of account of William Soper for 1422–27, for example, can be found in the collection of the National Maritime Museum, having formerly been part of the Phillipps collection, rather than at Kew in The National Archives.8 If they did remain at the Exchequer the clerks do not seem to have regarded their safe keeping as much of a priority. There are also accounts relating to individual royal campaigns or directed to particular ships’ masters for repairs, mariners’ wages, or for victualling ships. For certain periods, particularly in the fourteenth century when the monarchs were using the Chamber rather than the Exchequer as the royal office in charge of the finances of a war campaign, the details of payments to ships and their crews can be found in the Wardrobe Books. Details of accounts relating to shipbuilding and repairs from the reigns of Henry VII, when the office of Clerk of the King’s Ships was resuscitated, can be found in ledgers in the series called Exchequer Books.9

This picture well illustrates the problems in using pictures from medieval manuscripts as evidence for ship design; here it is easy to see that the waves have been depicted schematically. It is not so easy to interpret the way the hull of the ship has been shown.

(BRITISH LIBRARY)

Many other classes of documents also contain information about naval and maritime affairs. The most useful are probably the Patent and Close Rolls, which contain the text of writs and other royal orders directed by the King to individuals or corporations. These documents can be used to trace the careers of shipmasters or royal officials, or to find details of the gathering together of royal fleets. Complaints of robbery at sea may also appear here, along with the appointment of commissions of inquiry. Town archives, particularly those of London, Exeter and Southampton, also contain material about maritime matters, but most documents are more concerned with trading vessels and their cargoes rather...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Introduction: The Realm of England and Its Neighbours

- Chapter 1: The Sources for Medieval Maritime History

- Chapter 2: Strategic Imperatives

- Chapter 3: The ‘navy of England’: Understanding the Naval Resources of the Crown

- Chapter 4: Ships and Ship Types

- Chapter 5: Shipbuilding and Shore Facilities

- Chapter 6: The World of the Medieval Mariner

- Chapter 7: War at Sea

- Chapter 8: Corsairs and Commanders

- Chapter 9: The Navies of Other European States

- Chapter 10: The Legacy to Henry VIII

- Conclusion

- Further Reading

- Timeline

- Notes

- Acknowledgements