- 320 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

This is a comprehensive reference to the structure, operation, aircraft and men of Fighter Command from its formation in 1936 to 1968 when it became part of Strike Command. It includes descriptions of many notable defensive and offensive campaigns, the many types of aircraft used, weapons and airfields. The main sections of the book include a general historical introduction and overview, operations, operational groups, aircrew training and technical details of each aircraft type. Lengthy Annexes cover personnel, the squadrons in World War II, orders of battle for each wartime year, maps of airfield locations and numbers of enemy aircraft downed.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

CHAPTER ONE

Development, Roles and History

For a few short months in late 1940, Fighter Command of the Royal Air Force was pitted against the might of the German Luftwaffe in a struggle that would help determine the course of the Second World War. The Battle of Britain will always remain the Command’s ‘Finest Hour’ but it comprised only a few months of a war that lasted nearly six years – and Fighter Command was involved in active operations for much of that time.

As with all history the benefits of hindsight and access to previously classified documentary sources has to be balanced by the researcher’s removal in time and context from the period under study. To truly understand decisions, policies, actions and attitudes is all but impossible. This book covers the entire period of Fighter Command from its origin in 1936 to its demise – into Strike Command – in 1968. Whilst all periods of the Command are covered it is inevitable that the major focus is on the period of World War Two. The book has been divided into five main sections: an Introduction and Overview, which sets the framework for the development of Fighter Command and includes both policy and politics; an Operations chapter, which focuses on the combat operations of the Command; a brief look at each of the operational Groups; an overview of aircrew training; and, finally, an Aircraft chapter, looking in chronological sequence at all operational aircraft types. The annexes provide a variety of historical data.

The chapters frequently quote extracts from the Operational Record Books (ORB) of various squadrons; these have been selected as typical of the type of missions being flown. It would be impossible in a book of this sort to research every squadron record for Fighter Command and there are similar accounts, and perhaps better ones, in many of the other ORBs – if a reader believes ‘his’ squadron has been ignored I can assure him that that was not the intent!

Origins and doctrine

Fighter Command was formed on 14 July 1936, under the command of Air Marshal Sir Hugh Dowding, as part of a general reorganisation of the RAF, and headquartered at Bentley Priory, Middlesex. This reorganisation saw the Metropolitan Air Force split into three operational Commands (Fighter, Bomber and Training). At the time of its formation Fighter Command’s equipment comprised a variety of biplane fighters, the most modern of which was the Gloster Gladiator. As the first RAF fighter with eight machine-guns and an enclosed cockpit, the Gladiator represented a major advance on previous types and despite its obvious limitations was able to distinguish itself during the Battle of Britain.

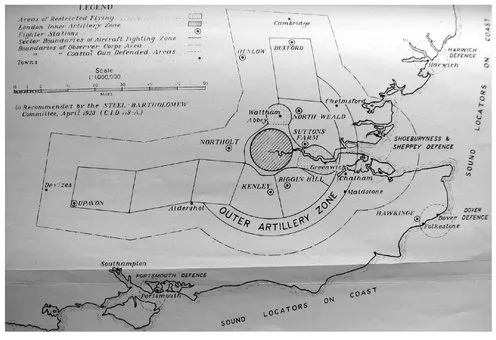

Since the early 1930s two key issues had plagued RAF planners – the percentage of bomber to fighters in the overall strength of the RAF and the types of weapons they should carry. There had been a glimmer of hope in the early 1920s, a period of doldrums for the RAF when its very existence as an independent service was under question and its main ‘strength’ was in remote parts of the Empire such as Mesopotamia. In April 1923 the Steel-Bartholomew Committee on the Air Defence of Great Britain led to Government approval in June of a plan for a Home Defence air strength of 52 squadrons, to include 17 fighter squadrons ‘with as little delay as possible’. As a percentage of the total strength the fighter element was poor – but this was the period when air strategists were convinced that bombers were the way to win wars. In December 1925 the Government’s interpretation of ‘as soon as possible’ changed to ‘by 1935 – 1936. Air Marshal Sir John Salmond had taken over as Air-Officer-Commanding Air Defence of Great Britain in January that year and he had firm views on air defence, which in his view – and his experience from World War One – included searchlights and anti-aircraft guns. In this study of Fighter Command only occasional reference is made to the other elements that made up the UK’s air defence network, primarily because they were independent Commands. It is worth noting that the ‘active defence‘ planned for the UK, and to be in place by 1939, comprised 2,232 heavy anti-aircraft guns, 4,700 searchlights and 50 squadrons of fighter aircraft. However, on the outbreak of war there were only 695 heavy and 253 light anti-aircraft guns and 2,700 searchlights.

Fighter doctrine and tactics were developed in the latter part of World War One, with aircraft such as the Sopwith Camel.

Map of the 1923 Air Defence Plan.

The Siskin was one of the inter-war agile but poorly-armed fighters equipping the RAF’s fighter force.

When the Gladiator entered service it was a major improvement on the previous biplanes but was still far from being a modern fighter, although it remained in front-line service with the RAF in the early part of the war.

In December 1929 and again in May 1933 the Government slipped the programme back, the latter revision taking it to 1939 – 1940. This reluctance did not change until 1934, a year after Hitler had come to power in Germany and there was a realisation that peace in Europe was by no means a certainty. The next few years saw a change of attitude and a series of Expansion Plans, albeit still dominated by strategic bombing.

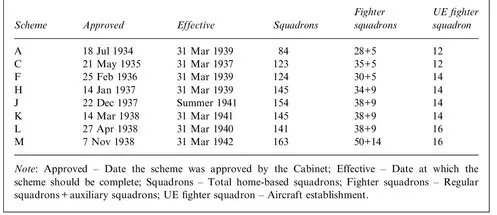

The ‘bomber first’ mentality that had dominated the Expansion Plans of the early 1930s did not change until Scheme M, which was approved in November 1938 (after the Munich Crisis), with an effective date for completion of March 1942. This scheme envisaged 163 squadrons to be based in the UK, of which 64 were to be fighter squadrons (14 of these being Auxiliary Air Force), each with an establishment of 16 aircraft. The table below presents the details for the Plans put forward between 1934 and 1938.

RAF Expansion Schemes, 1934-1938

This was of course only a paper air force; the desire to have 64 squadrons, each with 16 aircraft – and with the requisite pilots, ground staff, equipment and airfields – had to be transferred into reality. That meant taking short cuts with the aircraft types, ‘form a squadron with whatever was to hand and re-equip it later’ and pressure to find pilots, and train them in the minimum period of time. Both of these aspects would cause the Command problems.

Role of the Fighter

The concept of the fighter aircraft had been born in World War One, when manoeuvrability was one of the key performance criteria; for the Royal Flying Corps/ Royal Air Force, the experience with monoplanes had been an unhappy one and the war ended with small, single-seat highly-agile biplanes, armed with two 0.303 in guns, as the standard day fighter. The situation did not change over the next 20 years and the RAF’s fighter squadrons continued to fly a range of delightful little fighters that by the late 1920s had all but lost touch with the realities of a future air war – but the RAF’s doctrine, tactics and training had also not changed. It was not until the early 1930s that a more realistic specification for a future fighter was issued. However, Specification F10/35 still encapsulated the 1930’s fighter doctrine; the following extracts illustrate the major points.

Specification F10/35. Requirements for Single-Engine Single-Seater Day and Night Fighter

General. The Air Staff require a single-engine single-seater day and night fighter which can fulfil the following conditions:

- Have a speed in excess of the contemporary bomber of at least 40 mph at 15,000 ft.

- Have a number of forward firing machine guns that can produce the maximum hitting power possible in the short space of time available for one attack.

Performance.

- Speed. The maximum possible and not less than 310 mph at 15,000 ft at maximum power with the highest possible between 5,000 and 15,000 ft.

- Climb. The best possible to 20,000 ft but secondary to speed and hitting power.

- Service ceiling. Not less than 30,000 ft is desirable.

- Endurance. ¼ hour at maximum power at sea level, plus one hour at maximum power at which engine can be run continuously at 15,000 ft. This should provide ½ hour at maximum power at which engine can be run continuously (for climb, etc), plus one hour at the most economical speed at 15,000 ft (for patrol), plus ¼ hour at maximum power at 15,000 ft (for attack).

Armament. Not less than 6 guns, but 8 guns are desirable. These should be located outside the airscrew disc. Reloading in the air is not required and the guns should be fired by electrical or means other than Bowden wire. It is contemplated that some or all of these guns should be mounted to permit a degree of elevation and traverse with some form of control from the pilot’s seat.

Ammunition. 300 rounds per gun if 8 guns are provided and 400 rounds per gun if only 6 guns are installed.

View.

- The upper hemisphere must be so far as possible unobstructed to the view of the pilot to facilitate search and attack. A good view for formation flying is required.

- A field of view of about 10 degrees downwards from the horizontal line of sight over the nose is required for locating the target.

Handling.

- A high degree of manoeuvrability at high speeds is not required but good control at low speeds is essential.

- The aircraft must be a steady firing platform.

It is interesting to look at how the fighter requirement had changed during the 1930s as this explains the development of both the aircraft’s capabilities and the tactical doctrine. During the 1930s the basic concepts were still those that had been developed in the latter years of World War One; with no significant combat experience in the 1920s and in the absence of conflict (and funding) no appreciable development of technology or tactics this was not really surprising. The main fighter specification that eventually led to the new generation of fighters was F7/30 for a ‘Single-Seater Day and Night Fighter.’ This Specification was dated October 1931 and the General Requirements paragraph included statements such as ‘a satisfactory fighting view is essential and designers should consider the advantages offered in this respect by the low-wing monoplane or pusher. The main requirements for the aircraft are:

- Highest possible rate of climb.

- Highest possible speed at 15,000 ft.

- Fighting view.

- Capability of easy and rapid production in quantity.

- Ease of maintenance.

This was a lengthy document and amongst the key provisions was that the ‘aircraft must have a high degree of manoeuvrability.’ By the time of F10/35 this requirement had been toned down as being ‘not required’. The aircraft was to have provision for four 0.303 in Vickers guns and a total of 2,000 rounds of ammunition, with a minimum supply of 400 rounds per gun, as well as being able to carry four 201b bombs. It stated that two of the guns were to be in the cockpit, with interrupter gear if required, and the other two in cockpit or wing. There was no requirement for an enclosed cockpit and the pilot’s view was a prime concern: ‘the pilot’s view is to conform as closely as possible to that obtainable in ‘pusher’ aircraft.’ Virtually all of these requirements could be said to apply to an aircraft that suited the latter part of World War One, such as the Sopwith Camel or Bristol Fighter but with (slightly) improved performance. If the manufacturers had followed these requirements to the letter then the Spitfire and Hurricane might never have been born.

In terms of overall air doctrine the emphasis was on the bomber – the ‘war-winning’ weapon that will always get through no matter what the defenders try and do, but it was not until the mid 1930s that a fighter specification addressed the problem of shooting down these ‘war winners’. Whilst the basic provisions of F7/30 could be said to describe an agile, manoeuvrable fighter, those of F5/34 (dated 16 November 1934) tipped the balance to what is best described as a bomber destroyer. The introduction to this specification stated that: ‘the speed excess of a modern fighter over that of a contemporary bomber has so reduced the chance of repeated attacks by the same fighters(s) that it becomes essential to obtain decisive results in the short space of time offered for one attack only. This specification is issued to govern the production of a day fighter in which speed in overtaking the enemy at 15,000 ft, combined with rapid climb to this height, is of primary importance. In conjunction with this performance the maximum hitting power must be aimed at, and 8 machine guns are considered advisable.‘ No mention here of manoeuvrability; what is needed is to catch the enemy (bomber) and hit him hard in a single attack. All of this was encapsulated in F10/35 but with the added provisions under ‘Handling’ that emphasised the requirement for the fighter to be ‘a steady gun platform’ in which a ‘high degree of manoeuvrability at high speeds is not required.’ Of course, the British were not alone in this fighter theory and in Germany the Bf 110 came from a similar bomber-destroyer requirement. The latter proved a disaster...

Table of contents

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- Fighter Command Badge

- CHAPTER ONE - Development, Roles and History

- CHAPTER TWO - Operations

- CHAPTER THREE - Operational Groups

- CHAPTER FOUR - Aircrew Training

- CHAPTER FIVE - Operational Aircraft

- ANNEX A - AOC-in-C Fighter Command

- ANNEX B - Battle of Britain Squadrons

- ANNEX C - Battle of Britain: Galland’s View

- ANNEX D - Order of Battle July 1936

- ANNEX E - Order of Battle September 1939

- ANNEX F - Order of Battle August 1940

- ANNEX G - Order of Battle February 1941

- ANNEX H - Order of Battle April 1942

- ANNEX I - Order of Battle April 1943

- ANNEX J - Order of Battle July 1944

- ANNEX K - Order of Battle July 1945

- ANNEX L - Order of Battle April 1953

- ANNEX M - Order of Battle January 1961

- ANNEX N - Order of Battle January 1968

- ANNEX O - Claims World War Two

- ANNEX P - Definitions of Operation Types

- ANNEX Q - Fighter Command Battle Honours

- ANNEX R - German Night Attacks on Cities

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Fighter Command, 1936–1968 by Ken Delve in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Military & Maritime History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.