- 304 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

The author of

Case White: The Invasion of Poland delves into the strategy and weaponry of armored warfare during the early years of the Russo-German War.

The German panzer armies that swept into the Soviet Union in 1941 were an undefeated force that had honed their skill in combined arms warfare to a fine edge. The Germans focused their panzers and tactical air support at points on the battlefield defined as Schwerpunkt—main effort—to smash through any defensive line and then advance to envelope their adversaries.

Initially, these methods worked well in the early days of Operation Barbarossa and the tank forces of the Red Army suffered defeat after defeat. Although badly mauled in the opening battles, the Red Army's tank forces did not succumb to the German armored onslaught and German planning and logistical deficiencies led to over-extension and failure in 1941. In the second year of the invasion, the Germans directed their Schwerpunkt toward the Volga and the Caucasus and again achieved some degree of success, but the Red Army had grown much stronger and by November 1942, the Soviets were able to turn the tables at Stalingrad.

Robert Forczyk's incisive study offers fresh insight into how the two most powerful mechanized armies of the Second World War developed their tactics and weaponry during the critical early years of the Russo-German War. He uses German, Russian and English sources to provide the first comprehensive overview and analysis of armored warfare from the German and Soviet perspectives. His analysis of the greatest tank war in history is compelling reading.

Includes photos

The German panzer armies that swept into the Soviet Union in 1941 were an undefeated force that had honed their skill in combined arms warfare to a fine edge. The Germans focused their panzers and tactical air support at points on the battlefield defined as Schwerpunkt—main effort—to smash through any defensive line and then advance to envelope their adversaries.

Initially, these methods worked well in the early days of Operation Barbarossa and the tank forces of the Red Army suffered defeat after defeat. Although badly mauled in the opening battles, the Red Army's tank forces did not succumb to the German armored onslaught and German planning and logistical deficiencies led to over-extension and failure in 1941. In the second year of the invasion, the Germans directed their Schwerpunkt toward the Volga and the Caucasus and again achieved some degree of success, but the Red Army had grown much stronger and by November 1942, the Soviets were able to turn the tables at Stalingrad.

Robert Forczyk's incisive study offers fresh insight into how the two most powerful mechanized armies of the Second World War developed their tactics and weaponry during the critical early years of the Russo-German War. He uses German, Russian and English sources to provide the first comprehensive overview and analysis of armored warfare from the German and Soviet perspectives. His analysis of the greatest tank war in history is compelling reading.

Includes photos

Trusted by 375,005 students

Access to over 1 million titles for a fair monthly price.

Study more efficiently using our study tools.

Information

Chapter 1

The Opposing Armoured Forces in 1941

The German Panzerwaffe

The Wehrmacht initially deployed seventeen panzer divisions against the Soviet Union, organized into four Panzergruppen.1 Nine of the panzer divisions were less than a year old, having been formed from other existing infantry units between August and November 1940, when Hitler decided to double the number of panzer divisions. In practical terms, this meant that nearly half the panzer divisions involved in Barbarossa had no previous campaign experience in their current role. Nor was the internal structure of the panzer divisions uniform: eight were organized with two panzer battalions and nine divisions had three panzer battalions. The Panzergruppen were further divided into ten Armeekorps (mot.), later redesignated in early 1942 as Panzerkorps, with each controlling up to two panzer divisions and up to two motorized infantry units. The Panzergruppe (or Panzerarmee after October 1941) would be the primary German operational-level armoured formation of 1941–42, while the Panzerkorps would be the primary tactical-level formation.2 Previous campaigns had taught the Wehrmacht the value of concentrating armour, so it was rare for individual panzer divisions, brigades or regiments to operate independently in the first year of the war in the East.

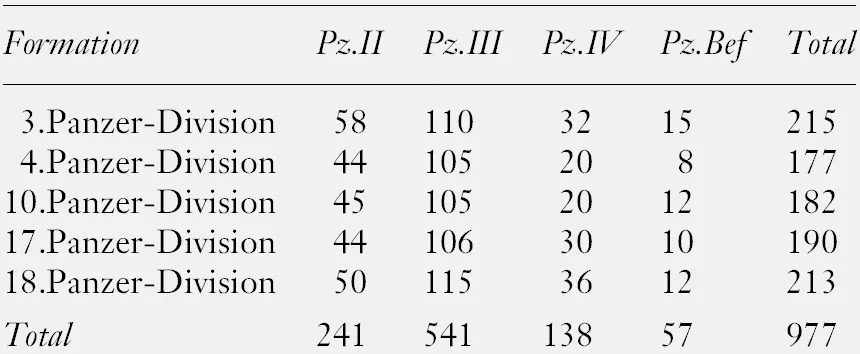

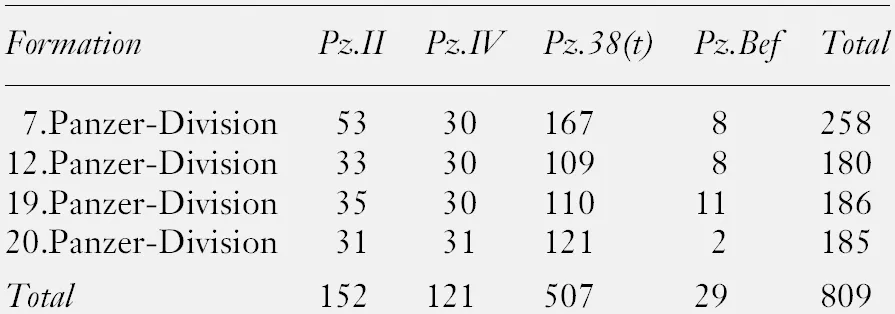

The bulk of the Panzerwaffe was massed with Heeresgruppe Mitte in the center, with Generaloberst Heinz Guderian’s Panzergruppe 2 and Generaloberst Hermann Hoth’s Panzergruppe 3. These two Panzergruppen had nine panzer divisions with a total of 1,786 tanks, or 57 per cent of the total available for Barbarossa. Guderian, who had fought so hard to promote the concept of an independent panzer branch before the war, now used the credibility that he gained as a corps commander in Poland and France to ensure that he was given the strongest panzer divisions for Operation Barbarossa. Panzergruppe Guderian would start the campaign with nearly 1,000 tanks in thirteen panzer battalions and all five of his divisions were fully equipped with Pz.III medium tanks. In contrast, Hoth’s Panzergruppe 3 had a total of twelve panzer battalions in four panzer divisions, none of which were equipped with Pz.III medium tanks. Instead, Hoth was provided with 507 Czech-made Pz.38(t) light tanks, equipped with the 3.7cm Skoda A7 cannon. The Pz.38(t) tanks were still in production by BMM in Prague and had better mobility than the Pz.III Aus F/G models, but significantly less armour and firepower. Indeed, Hoth’s Panzergruppe was primarily configured as a pursuit force and had negligible anti-armour capability.

Generaloberst Guderian’s Panzergruppe 2 (Heeresgruppe Mitte)

Generaloberst Hoth’s Panzergruppe 3 (Heeresgruppe Mitte)

Generaloberst Höpner’s Panzergruppe 4, which was tasked to support Heeresgruppe Nord’s advance toward Leningrad, was the smallest German armoured formation given an independent mission in Barbarossa. Höpner had three panzer divisions, comprising eight panzer battalions with 590 tanks. His panzer units were all veteran outfits, but equipped with a motley collection of German and Czech-made tanks. In particular, the 6.Panzer-Division was primarily equipped with obsolescent Czech Pz.35(t) light tanks, which had no spare parts available even at the start of the campaign. The Czech Pz.35(t) was not mechanically reliable enough for a protracted campaign and none would remain in front-line combat service after October 1941. The 1.Panzer-Division was particularly fortunate in having two out of its four Schützen Abteilung (rifle battalions) equipped with a total of nearly 200 Sd.Kfz.250 and Sd.Kfz.251 half tracks.

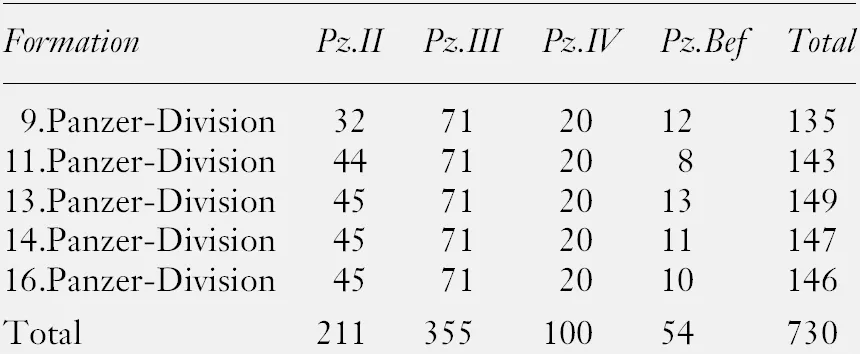

In southern Poland, Generaloberst von Kleist’s Panzergruppe 1 was assembled to spearhead Heeresgruppe Süd’s advance toward Kiev. Kleist was given the second-best equipped Panzergruppe after Guderian, with ten panzer battalions in five panzer divisions, with a total of 730 tanks. Kleist’s command had no Czech-built tanks and a good number of Pz.III medium tanks, but he also had significantly more ground to cover in his objectives than the other Panzergruppen. Abwehr intelligence estimates on Soviet tank strength and dispositions were poor, but sufficient to indicate that Kleist would be up against some of the strongest formations available to the Red Army. Thus, it would come as little surprise that Kleist would need help from at least one other Panzergruppe to complete his mission.

Generaloberst Höpner’s Panzergruppe 4 (Heeresgruppe Nord)

Generaloberst von Kleist’s Panzergruppe 1 (Heeresgruppe Süd)

The main combat elements of the 1941 Panzer Division were a panzer regiment (some divisions still had panzer brigade headquarters) with two or three panzer battalions; two Schützen (motorized infantry regiments) with a total of four battalions; a Kradschützen battalion (motorcycle infantry); an Aufklärungs Abteilung (reconnaissance battalion); a motorized artillery regiment with a total of thirty-six towed howitzers; a Panzerjäger Abteilung with towed 3.7cm and 5cm Pak guns and a motorized pioneer battalion. Most of the infantry rode in trucks, but panzer divisions were beginning to receive the excellent Sd.Kfz.250 and Sd.Kfz.251 half tracks; about 560 were available at the outset of Barbarossa. Altogether, the panzer division was authorized a total of 5,300 infantry in the five Schützen and Kradschützen battalions. A 1941 panzer division had a total of about 4,100 vehicles. The organization of a Panzer Abteilung (battalion) was far from standardized in June 1941, but its combat elements were authorized two or three light companies (equipped with Pz.III, Pz.35(t) or Pz.38(t)) and one medium company with Pz.IVs. All told, an ideal, full-strength Panzer Abteilung would have between sixty-six and eighty-eight tanks (fifteen to twenty Pz.II, thirty-five to fifty-two Pz.III, fourteen Pz.IV, two Pz.Bef) and 625–780 men.3 Although a number of obsolete Pz.I light tanks were still in the panzer division, they were not in the panzer regiments but in the panzer pionier-bataillon, where they served as mine-clearing vehicles.

Major sub-units in the Panzer Division

The main German battle tank employed in Operation Barbarossa was the Pz.III, with the newer Ausf G and H models representing the best available to the Panzerwaffe at that time. These models, both armed with the 5cm KwK 38 L/42 cannon, were better in terms of firepower and protection than the T-26 or BT-series light tanks which still comprised the bulk of the Red Army’s tank forces. The Pz.III was intended to defeat enemy tanks and carried a typical basic load of eighty-five armour-piercing and fifteen high-explosive rounds. The standard 5cm Panzergranate 39 armour-piercing round could penetrate up to 47mm of armour at 500 meters, enabling the Pz.III Ausf G or H to defeat all Soviet light tanks at typical battlefield ranges. The Pz.III would even be able to inflict damage on the Soviet T-34, using Panzergranate 38 with flank or rear shots fired from ranges under 500 meters; difficult, but not impossible. The 5cm Panzergranate 40, which had much better armour-piercing capability due to its tungsten penetrator, entered production just before the start of Barbarossa and was available only in limited numbers; for example, Panzergruppe 4 had enough Panzergranate 40 available to equip each Pz.III with just five rounds.4 While the Pz.III’s antiarmour firepower was modest, its main limitation was its tactical range of barely 100km on a single load of fuel, which was not very impressive. The Pz.IV medium tanks, armed with the 7.5cm KwK 37 L/24 howitzer, were armed with a mix of fifty-two high explosive rounds, twenty-one armour-piercing rounds (k.Gr.rot.Pz. (APC) or Panzergranate) and seven smoke rounds at the start of Barbarossa.5 While the 7.5cm k.Gr.rot.Pz. round could penetrate up to 39mm of armour at 500 meters, its low velocity made it poorly-suited for anti-tank combat against T-34 or KV tanks. In an effort to improve firepower, the Germans were developing a new type of High Explosive Anti-Tank (HEAT) rounds for the 7.5cm howitzers on Pz.IVs and StuG III assault guns, but they would not be available until the end of 1941. In actuality, both the Pz.IV and StuG III were only suited for the infantry support role in 1941, leaving the Pz.III as the sole effective dual-purpose tank employed by the Panzerwaffe in Barbarossa. In addition to the panzers, the Wehrmacht deployed twelve Sturmgeschütz-Abteilung with over 200 StuG III assault guns and five Army-Level Panzerjäger-Abteilung equipped with 135 Panzerjäger I tank destroyers. The Panzerjäger I was an improvisation, with the high-velocity Czech-made 4.7cm cannon mounted atop an obsolete Pz.I chassis; the 4.7cm was one of the best anti-tank weapons available to the Wehrmacht at the start of Barbarossa.

Nearly one-quarter of the German battle tanks heading into the Soviet Union were Pz.II light tanks, which were already obsolescent in the previous French campaign. Unlike the Pz.I, the Pz.II still played a major role in German tank platoons and companies. Although often used as a scouting tank, the Pz.II tank had better armoured protection than either the T-26 or BT-series light tanks and its rapid-firing 2cm KwK 30 cannon could penetrate their armour at ranges under 500 meters. The Pz.II would also play a useful role in escorting supply convoys through forested areas infested with Soviet partisans.

Despite much media publicity about Germany’s so-called Blitzkrieg doctrine both during and after the war – which was intended to create the impression of short, successful campaigns – the Panzerwaffe had a relatively amorphous doctrine in 1941. One of the key components of this doctrine was a preference for combined-arms tactics in mixed kampfgruppen; tank-pure tactics were rejected as foolhardy and inefficient. As an example, the 4.Panzer-Division’s Kampfgruppe Eberbach in early July 1941 was comprised of one Panzer-Abteilung, one Kradschützen Kompanie (motorcycle infantry), a Schützen Kompanie (Mechanized Infantry) in SPW half tracks, an artillery battalion (twelve towed 10.5-cm howitzers), two Pioneer Kompanie, part of a Brückenkolonne, one heavy flak battery (8.8cm) and one light flak battery (2cm). All told, Kampfgruppe Eberbach started with about 2,300 troops and 750 vehicles. Other variations included Panzerjäger and Aufklärungs (reconnaissance troops), as well as more infantry. Each panzer division would normally form three kampfgruppen, usually one that was tank-heavy and two that were infantry-heavy.

Another key component of the German doctrine was extensive use of radios in tactical vehicles to ensure effective command and control. German panzer units operated company, battalion, regiment and division-level radio networks, which enabled timely sharing of combat information and provided German commanders with excellent situational awareness. Using the Medium Frequency (MF) Fu-8 or Very High Frequency (VHF) Fu-6 radios mounted on a Panzerbefehlswagen III (armoured command vehicle) or a Sd.Kfz.250/3 half track, a German panzer kampfgruppe commander could exercise command over a 40km radius while moving and up to 70km while stationary. German panzer platoon and company radio nets relied upon the VHF Fu-2 and Fu-5 radios, with a 2–4km radius of control. The mounting of radios in every panzer allowed the Germans to get the most out of their available armour and mass it where it was needed most. Furthermore, the use of the Enigma encryption device gave the Germans a secure means of communicating orders between divisions, corps and armies. Although German panzer units lacked direct air-ground communications with Luftwaffe units in June 1941, requests for air support could be passed from forward kampfgruppen up through the division radio net in a reasonable period of time.

German operational and tactical-level panzer doctrine incorporated elements of the Stosstruppen tactics of 1918, with a preference for infiltration and encirclement, rather than costly, frontal attacks. The Germans also learned first-hand in the streets of Warsaw on 8 September 1939 that panzer divisions fared poorly in cities, although this lesson would often be ignored during the Russo-German War. Instead, the panzer divisions were intended to create a breach in the enemy front on favorable terrain – with help from infantry, artillery and the Luftwaffe – and then advance rapidly to encircle the enemy’s main body before they could react. The panzers would push boldly ahead of the non-motorized infantry divisions, who would have to rely upon assault-gun batteries for close support in completing the breakthrough battle. German doctrine assumed that once enemy units were encircled in a kessel, that they would either quickly surrender or be annihilated with concentric attacks. The doctrinal preference was to use pairs of panzer divisions or corps to encircle an enemy with double envelopments, rather than the riskier single-envelopment approach. Thus, the German doctrinal solution to the Red Army was to conduct successive battles of encirclement until the best Soviet units were demolished. However, the doctrine employed by the German Panzerwaffe had two primary flaws, which had not appeared in previous campaigns. First, the Germans could not logistically sustain a series of panzer encirclements indefinitely; eventually fuel shortages and mechanical defects would bring the advance to a halt and that might give the enemy a chance to recover. Second, the doctrine was developed at a time when anti-tank defenses were relatively weak, which enabled panzer divisions to run roughshod over most infantry divisions caught in open terrain. Yet as Soviet anti-tank defenses steadily improved in 1942–43, German panzer leaders continued to believe that enemy infantry could not stop an envelopment from occurring.

The men leading the panzers into the Soviet Union were a well-trained and professional cadre, but nearly one-third had little or no direct experience with tanks. Indeed, many German senior armour leaders in 1941 were still learning their trade and not completely aware of the capabilities and limitations of tanks. Half of the top thirty-one panzer leaders came from the infantry branch and one-third from the cavalry. At the most senior level, Generaloberst Ewald von Kleist of Panzergruppe 1 had more experience with commanding large panzer formations than any other officer in any army, although he had never actually served in a panzer unit. Generaloberst Heinz Guderian, commander of Panzergruppe 2, had commanded a panzer division and led his motorized corps in Poland and France, but was the only non-combat arms officer in command of panzer units in Operation Barbarossa. As a signal corps officer turned mechanization advocate, Guderian remained something of a dilettante throughout his career and had the impulsive, undisciplined nature of a military maverick – he was not a team player, but an individualist. Six of the ten commanders of motorized corps in June 1941 had previous battle command experience with a corps, but three – including General der Infanterie Erich von Manstein – had no personal experience with panzer units. Only three panzer corps commanders: General der Panzertruppen Georg-Hans Reinhardt, General der Panzertruppen Leo Freiherr Geyr von Schweppenburg and General der Panzertruppe Rudolf Schmidt had both extensive corps command experience and had previously led a panzer division in battle. Hitler’s creation of ten new panzer divisions in late 1940 diluted the division leadership pool somewhat and, by the start of Barbarossa, only eight of the seventeen panzer division commanders had previous division command experience and five of the seventeen were new to the Panzerwaffe. A number of the new panzer division commanders, such as Generalleutnant Walter Model, had primarily been staff officers with limited command experience. The German officers tended to be older than their Soviet counterparts due to Stalin’s purge of the Red Army, with the average age of the top thirty-one panzer commanders being fifty-three.

At the platoon, company, battalion and regiment level, German tankers were very well trained in operating their vehicles and there was a high proportion of combat veterans. All had been trained at either Panzertruppen Schule I in Munster or Panzertruppen Schule II in Wünsdorf, which helped to standardize skill levels across the Panzerwaffe. Most panzer divisions passed the winter of 1940–41 in France or Germany, with considerable time spent in gunnery and maneuver training. Units rotated through training areas such as Grafenwöhr or Warthe, as well as gunnery training at the Putlos range on the Baltic. The German tank crews were extremely well-trained in their basic tasks of driving, loading and gunnery and were cross-trained in order to fill gaps created by casualties. German tankers were also trained to conduct routine maintenance, but they were not so handy at mending thrown track, conducting battlefield recovery or repairing simple defects; they tended to wait for their I-Gruppe (Instandsetzungs...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Plates

- List of Maps

- Glossary

- Preface

- Introduction

- Chapter 1: The Opposing Armoured Forces in 1941

- Chapter 2: The Dynamic of Armoured Operations in 1941

- Chapter 3: Armoured Operations in 1942

- Conclusions

- Appendix I: Rank Table

- Appendix II: Armour Order of Battle, 22 June 1941

- Appendix III: Tanks on the Eastern Front, 1941

- Appendix IV: Tank Production, 1941

- Appendix V: Armour Order of Battle, 1 July 1942

- Appendix VI: Tank Production, 1942

- Notes

- Bibliography

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Tank Warfare on the Eastern Front, 1941–1942 by Robert Forczyk in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & German History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.