- 144 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

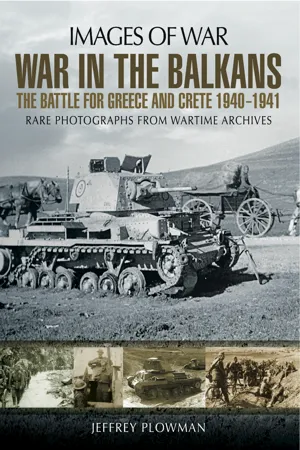

This WWII pictorial history presents a vivid look at the Balkan campaign from Italy's invasion of Greece to the Nazi airborne assault on Crete.

Through rare wartime photographs, War in the Balkans traces the course of the entire Balkan campaign. Beginning with Mussolini's first act of aggression, the narrative continues through Albania, the invasions of Yugoslavia and Bulgaria by German forces, and on to the battle for Greece and the final airborne assault on Crete.Historian Jeffrey Plowman gives equal weight to every stage of the campaign and covers all the forces involved: the Italians, Germans, Greeks, and British Commonwealth troops. By shifting the focus to the mainland—rather than the culminating Battle of Crete—Plowman views the campaign as a whole, offering a balanced portrayal of a conflict that is often overlooked in histories of the Second World War.

Most of the photographs included here have never been published before, and many come from private sources. They are a unique visual record of the military vehicles, tanks, aircraft, artillery and other equipment used by the opposing armies. They also show the conditions the soldiers faced, and the landscape of the Balkans over which they fought.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access War in the Balkans by Jeffrey Plowman in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & World War II. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter One

The Greco-Italian Conflict, 1940-1

There is no doubt that Mussolini was jealous of Germany’s annexation of Austria, so it came as no surprise when he asserted Italian control over Albania by sending in troops on 7 April 1939. This action prompted the Prime Minister of Britain, Winston Churchill, to offer to support the sovereignty of both Greece and Rumania should they be threatened and a month later a similar offer was made to Turkey. Not that that this was of any benefit to Rumania as in June, with Hitler’s encouragement, Bulgaria, Hungary and Russia stripped it off its frontier provinces. As a sign of things to come the governor of Albania began agitating the Greeks on behalf of the Cham Albanian minority in Greek Epirus. After the headless body of an Albanian bandit was discovered near the village of Vrina he blamed the Greeks and began arming some of the Albanian irregular bands. It was therefore just a matter of time before Mussolini made his next move against Greece.

One incident that the Greeks blamed on Italy was the torpedoing and sinking, with heavy loss of life, of their cruiser Helle by a submarine on 15 August 1940 when she was anchored off Tinos. Though taking no action against Italy, the President of the Greek Council, General Ioannis Metaxas, did ask what help Greece could expect from Britain; not that Churchill could offer much, other than naval support. The situation deteriorated further the following month when Italy sent three more divisions to Albania. This led Britain to discuss the possibility of a coordinated defence of Crete but the Greeks would not allow any landings on their soil without a declaration of war. Nor did the Italians have much luck either in their discussions with Germany. When they sought German support for an attack on Jugoslavia, Adolf Hitler was adamant that he did not want to see the war spread to the Balkans. As a result Mussolini switched his attention to Libya and on 13 September launched his forces on a drive into Egypt. Not that he turned his back on Greece entirely but, assured by the governor of Albania that there would be no difficulty in securing Epirus and Corfu if he decided to attack Greece, he drew up plans for the invasion. In preparation for this three more divisions were dispatched in September. Nevertheless, by October Mussolini had started to waver in his plans and it was only after Hitler sent a strong military mission to Rumania that he became aware of Germany’s true interest in the Balkans and finally resolved to proceed with his plans to invade Greece.

Thus it was at 3 am on the morning of 28 October that the Italian minister in Athens presented the Greek government with a note charging them with having systematically violated their neutrality, particularly with respect to their dealings with the British, by allowing their territorial waters and ports to be used by the British navy and their refuelling facilities to be used by the RAF. Metaxas’ immediate response was to reject these demands, with the result that 3 hours later the first Italian troops crossed the frontier into Greece.

The British response to this was to send a naval flotilla into the Ionian Sea on 29 October. It sailed as far as Corfu before returning to the west coast of Crete to await the arrival of a force charged with garrisoning Crete and setting up a naval refuelling base in Suda Bay. This force had been dispatched the same day from Alexandria carrying the 1st Battalion of the York and Lancaster Regiment. They arrived on 1 November and were followed soon after by what anti-aircraft, engineer and ancillary units the Commander in Chief of the Middle East, General Archibald Wavell, had reluctantly agreed to release. At that stage the only airfield was at Heraklion, 70 miles to the east, and too far away to provide air protection for the naval base so work began on another airfield for fighter aircraft at Maleme. Pleased with these moves, the Greeks withdrew the Crete Division from the island. However, their concern with the non-appearance of British aircraft prompted the British to arrange for the dispatch of Blenheims from 30 Squadron and Gladiators from 80 Squadron, though the Greeks forbade them from being stationed any further north than Eleusis or Tatoi to avoid provoking the Germans.

As it turned out the invading Italian forces were in for a rude shock. Expecting little resistance from the Greeks, the Italians launched their attack in the Epirus sector on the Greek Elaia–Kalamas River Line, with a flanking attack in the Pindus Mountains. Starting in the morning, 51 Divisione di Fanteria ‘Siena’ and 23 Divisione di ‘Ferrara’ backed by the Centauro Armoured Division thrust towards Elaia, prompting the Greeks to begin a slow withdrawal in that direction. On 2 November, despite being under bombardment from the air and artillery, the Greeks easily fought off repeated attacks, while the tanks of the 131 Divisione Corazzata ‘Centauro’ wallowed in the marshy terrain. More success was had to their right as the Littoral Group, after a slow advance along the coast, secured a bridgehead over the Kalamas River on 6 November. On their left flank the 3 Divisione Alpina ‘Julia’ pushed through the mountains to capture the village of Vovousa but was unable to secure the critical pass at the town of Metsovo. Unfortunately at this point disaster struck when their troops found themselves entirely cut off by the arrival of Greek reserves and were virtually wiped out in the subsequent fighting. However, by then the fight had gone out of the Italians and on 8 November their offensive came to a halt.

At this point the Greeks responded by launching a counter-offensive on 14 November. With in a week they had captured Koritsa and Leslovik and re-crossed the Kalamas River. To add insult to injury they not only regained their lost territory but carried the war into Albania, penetrating deep into the mountains in the northwest of Koritsa. In the south they took the port of Santa Quaranta, thus restricting the Italians to the port of Durrës and the size of the forces they could keep in the field. In the centre the Greeks made good progress towards Berat and by 10 January 1941 had secured Klissoura, though were still short of their goal of taking Tepelene. By now, however, the weather, with frequent blizzards, was taking its toll on their troops, with cases of frostbite common. This was not the only reverse Mussolini suffered. In North Africa the British launched their counter-offensive which not only drove the Italians out of Egypt but by January 1941 saw them in headlong retreat along the Cyrenaican coast.

The British were not slow to respond to the fighting in Albania but reacted in quite a different way. Noting the reluctance of the Italian fleet to force the issue at sea, Admiral Cunningham decided instead to launch an attack on the Italian battle fleet in Taranto harbour. Originally planned for Trafalgar Day, 21 October, the attack had to be deferred till 11 November thanks to a fire in the hangar of HMS Illustrious. The attack was carried out in two waves that night, two aircraft dropping flares east of the anchorage and bombing the oil storage depot, while Fairy Swordfish torpedo bombers, coming in from the west, attacked the main anchorage. As a result, two ships were hit and damaged for one aircraft lost. The second wave arrived at the harbour around midnight, hitting one additional ship, also losing one aircraft. By the end of the attack half of the Italian capital ships had been put out of action, two for at least six months. The success was not confined to this as later that night a raiding force sank another four Italian merchant ships in the Adriatic Sea.

A Pavesi artillery tractor being unloaded at a port in Albania during the build-up of Italian forces. (Daniele Guglielmi)

One of the unit’s Obice da 100/17 howitzers being swung ashore. (Daniele Guglielmi)

A column of Pavesi tractors and guns making their way up to the front line in Albania, 1940. (Daniele Guglielmi)

Italian artillery in action during the campaign in Albania. (Daniele Guglielmi)

Among the armour the Italians deployed in Albania were these L3/33 tankettes. (Daniele Guglielmi)

Chapter Two

Opposing Plans in the Balkans

One of the consequences of the turn of events in Albania and the raid on Taranto was to push Germany into supporting Italy in her Balkan venture, though this was as much driven by their concern that the British were in a position to bomb the Rumanian oil fields that Germany had only recently secured. On 4 November Hitler requested that an examination be made of the possibility of sending troops to support the Italians in Greece, though he made it plain to them that this could not be done before March 1941 when the weather was more favourable. What he did not do was tell them of his plans to invade Russia, confining himself to saying that he would need his forces back by the beginning of May. In the meantime he made available Fliegerkorps X, then in Norway, for use against military and economic targets, with the special task of trying to eliminate the British fleet. It started to arrive in Sicily in late December, bringing 186 aircraft of all types, including 96 bombers and 25 twin-engined fighters. Though they were not able to bring the British Mediterranean Fleet to heel, they did score one success on 11 January 1941 when the aircraft carrier HMS Illustrious was damaged by a force of thirty to forty Ju 87s and 88s and had to put into Malta for repairs.

In accordance with their plans early in January 1941 the Germans began to move into Rumania by way of Hungary, ostensibly to help organize and train Rumanian forces but it fitted in with their ultimate plan to have troops in position for their invasion of Russia. The directive for the Operation Marita, issued by Hitler on 13 December 1941, called for the occupation of Greek Macedonia and possibly the whole of Greece, if necessary, to stop the British using it as a base to threaten Italy or Rumania. Just how Bulgaria would react was not certain. Despite having been invited to join the Tripartite Pact between Germany, Italy and Japan, it had still not come to a decision. Likewise, it was not clear whether Jugoslavia would allow the Germans to pass troops through their territory unchallenged. One thing was certain, the Russians had not been fooled by Hitler’s explanations of his intentions and continued to follow events in the Balkans with considerable interest.

For the forthcoming invasion Generalfeldmarschall Wilhelm List’s 12.Armee had 4 panzer, 1 motorized, 2 mountain and 11 other divisions, all backed up by 153 bombers and 121 fighters of Fliegerkorps VIII. Bad weather, however, brought delays to the programme, particularly treacherous ice on the Danube, the crossing of which had to be put off until early March. Thus, the launch date for the attack on Greece was set for the beginning of April.

It did not take long for the British to learn of developments in Rumania. It was also becoming increasingly apparent that it was Germany’s ultimate intention to launch an attack on Greece via Bulgaria. As a result the British decided to make another offer of support to the Greeks. Wavell was also told that Greece was to take priority over all other operations once his troops reached Tobruk in Libya, unless an advance to Benghazi seemed possible. On 13 February Wavell headed a British delegation to Athens where he met with Metaxas and senior Greek officers. Wavell offered them two field artillery, one medium artillery and one anti-tank regiment, plus one or two batteries of anti-aircraft artillery and a tank regiment, all of which Metaxas refused. His reason being that it would not achieve the desired results and most likely further provoke the Germans. Instead, their main interest was in resolving ...

Table of contents

- Front Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Photograph Sources

- Introduction

- Chapter One The Greco-Italian Conflict, 1940-1

- Chapter Two Opposing Plans in the Balkans

- Chapter Three Germany Enters Bulgaria and Jugoslavia

- Chapter Four Opening Moves in Greece

- Chapter Five From the Aliákmon Line to Thermopylae

- Chapter Six The Flight of 1 Armoured Brigade

- Chapter Seven The Evacuation of W Force

- Chapter Eight Operation Merkur

- Chapter Nine The Battle for the Airfields

- Chapter Ten The Retreat to Sfakia

- Epilogue