eBook - ePub

Narrow Gauge in the Arras Sector

Before, During & After the First World War

- 272 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

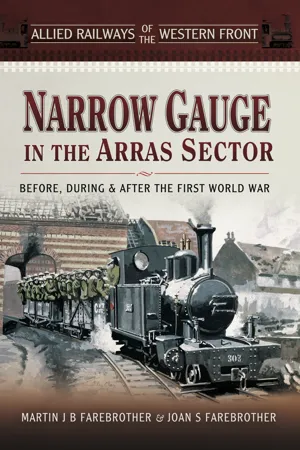

Narrow Gauge in the Arras Sector

Before, During & After the First World War

About this book

The Arras sector of the Western Front in World War I (WW1) was held partly by the British and Dominions 1st Army from September 1915, and almost wholly by the 1st and 3rd Armies from March 1916. No less than in the Ypres sector to the north and the Somme sector to the south, the struggles of the French and then British troops in this sector were pivotal to the outcome of the War. The sector included countryside in the south, but in the north a major part of the industrial and coal-mining area of northern France, around Lens and Bthune. In this book the contribution of metre and 60 cm gauge railways to the Allied war effort in this sector is examined in the context of the history of the metre gauge lines already established. The build up of light (60 cm gauge) lines from 1916 is examined in detail area by area, and the contribution of the related metre gauge lines is reassessed, from British and French sources. After the War the role of these railways in the reconstruction and recovery of this devastated region of France is described. Later the surviving part of the 60 cm gauge network served the sugar beet industry east of Arras. The history is followed through another World War to the closure of the last of these railways in 1957.The book refers to previous works on British War Department light railways in WW1, but contains sufficient general information for readers new to the subject. It also describes how to find key locations now, and how and where rolling stock can be seen. Six walks and an urban tour are included for those who wish to explore the territory in greater depth.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Narrow Gauge in the Arras Sector by Joan S. Farebrother,Martin J.B. Farebrother in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & World War I. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter One

Introducing the Arras Sector and its Railways

The Arras sector corresponds mainly with the eastern part of the département of Pasde-Calais. North of La Bassée, the front line for most of the First World War was on or near the boundary with the Nord département, in the areas of Neuve Chappelle and Fromelles. North of this, the front line crossed the very narrow part of the Nord département at Armentières, and then into Belgium (see Figure 0.1, with the introduction). The Pas-de-Calais département is the fifth largest in France. The capital of Artois, Arras, is the Préfecture of the département. In 1982 the Nord and Pas-de-Calais départements became the région Nord-Pas-de-Calais, with the administrative centre in Lille, Préfecture of the Nord département.

The western part of the Pas-de-Calais is, perhaps, better known to English visitors than the eastern, since not only is it nearer, but also it boasts a fine coastline with famous cliffs and wonderful beaches. The eastern part, the main setting for this book, has stretches of beautiful countryside, but also contains some of the most industrialised areas in France. Until the French stopped mining this area in 1990, coal was the basis for its industrial development. However, long before the coal was first brought to the surface, this part of northern France was already a prosperous manufacturing area.

History

The area covered by the Pas-de-Calais département is that of the old Comté (County) of Artois. In the thirteenth century France, following trouble with Flanders, was anxious to secure her Northern borders, hence the Comte d’Artois became a key player. In 1237, Louis IX therefore gave the county to his younger brother, Robert, in order to secure the succession of the area for the crown. In the fourteenth century a daughter inherited Artois and by her marriage to Phillip the Bold, Duke of Burgundy, the county was absorbed into Burgundy. Thus by the fifteenth century Arras, as the capital of Artois, had become a very important town with a ducal palace and frequent visits by the Burgundian court.

The rise of Burgundy continued to threaten France, and in 1414 (the year before Agincourt) the French laid siege to Arras but after several frustrating months they gave up and returned to Paris. Things continued in this way throughout the fifteenth century with another unsuccessful siege in 1475. It was only with the death of Charles the Bold in 1477 that France was able to take Arras. It was not to last, however; Burgundy had passed to Charles’ only child, a daughter, Mary. She married Maximillian Hapsburg who soon took Arras back from the French to make it part of the Spanish Netherlands. Battles for the city continued, with the French gaining it in 1640 but losing it in 1654. All was finally settled with the Peace of the Pyrenees, in 1659, and Arras became French. It was still seen as a frontier town and Louis XIV set his military architect, Vauban, to build the citadel, which still stands. For about 250 years Arras prospered peacefully, but all was to change in the twentieth century when she found herself once again on the front line and under siege.

1.1 The Town Hall (Hôtel de Ville) in the Petite Place (now the Place des Héros) in Arras. Photograph taken before the First World War. (Authors’ collection)

1.2 The area near the Town Hall in Arras, showing some of the damage suffered in the First World War. The damaged belfry of the Town Hall can be seen back right. Photograph probably taken after the war, with a light railway being used for tipper trucks to clear the rubble. (Authors’ collection)

Geography

The Eastern Pas-de-Calais is an area of geographical contrasts. Turning the clock back many millennia to before the last Ice Age, what are now called the Weald of Kent and the Pas-de-Calais were joined together. For this reason they share the same chalky soil. The Strait of Dover (in French the Pas-de-Calais, after which the département is named) is now believed to have been formed over 425,000 years ago. The current view of the cause for this is that an ice-dammed lake in the southern North Sea burst and the land bridge was swept away. The resulting strait is 19 miles across at its narrowest point. The chalk of Dover Cliffs therefore continues into France, where it first appears as Cap Blanc-Nez. The chalk continues to run down across the Pas-de-Calais as a dramatic escarpment, notably seen at Vimy Ridge and Notre Dame de Lorette, near the centre of our area. Back from the edge on the chalk uplands, the scenery changes to pleasantly fertile and wooded areas. Artesian wells were first discovered in this area, artésian meaning ‘of Artois’. The chief crops of this area are wheat, maize and sugar beet. At the bottom of the ridge you are suddenly on the heavy clay of Flanders.

Overall the watershed runs from northwest to southeast. North and east of this the rivers, notably the Scarpe and the Lys, flow across the plain to the North Sea. A good number of these are navigable, and there are numerous canals, especially down on the plain. This was notable for its windmills. The railways we will describe also stretch south and west of the watershed, to the river Canche, which flows west into the English Channel. Further south is the Authie, which is for most of its course the boundary between the départements of Pas-de-Calais and Somme, and therefore historically the division between Artois and Picardy.

Coal Mining

The extensive coal fields of the Pas-de-Calais – the majority around Béthune and in the Gohelle area around Lens – are part of the coal basin that extends from Kent through Belgium via Mons and Charleroi into Germany and the extensive mines of the Ruhr. In France, the seam (gisement) runs for 120km, varying in width from 4 to 12km. The depth of the seam varies tremendously, adding to the difficulty of extraction, and frequent rock falls led to numerous accidents. Coal was first discovered near Boulogne in 1682 but the first large find was near Fresnes in 1720. This coal, however, was of poor quality. In 1734, a rich seam was discovered at Anzin, near Valenciennes, in what is now the Nord département. The Anzin Company was formed in 1757 from smaller mines, and this became ultimately the most profitable mine in the area, with its shares rising from 300 Francs to 23,000 Francs in 1893. By the French Revolution there were thirty pits in the area producing a million tonnes of coal per year. In the nineteenth century the mines benefitted from the mechanical improvements of the Industrial Revolution. Coal was discovered in the Pas-de-Calais area at Oignies in 1842, and was followed by rapid expansion of the Pas-de-Calais coal fields. A major change, of course, was in transport, and the railways soon monopolised the movement of coal from the mines and the delivery of supplies.

1.3 Fosse (coal mine) No. 1 of Liévin. Postmarked 26 August 1914. See also Area 4, chapter five, and A tour in Lens and Liévin, chapter twelve. (Authors’ collection)

Until the First World War the industry prospered, with mines in the hands of a few companies who were able to exploit their asset for the benefit of usually absent shareholders. During the Great War, a large part of the coal field around and east of Lens was in German hands, and they helped themselves to much equipment from the mines on their side of the front line. However, the miners still had to produce the coal needed to help Germany’s war effort. The 1920s saw boom time, followed by the great depression of the 1930s. With the German invasion of 1940, history repeated itself. This time the French miners were less biddable; many joined the Resistance, and in 1941 a strike led to 200 miners being shot in Arras and 250 deported to Germany. By the end of the war coal was scarce and in great demand. So miners were recruited from Poland, Italy and North Africa. There were major strikes in 1947 and 1949, and by the 1950s miners were the best paid workers in France. The increasing difficulty of extraction and a decreasing demand for coal led to falling outputs. In 1959, 29 million tonnes were mined. By 1977 this had fallen to 6.6 million tonnes, 3.2 million tonnes by 1983, and 1.3 million tonnes by 1987. The number of miners fell accordingly from a peak in 1953 when there were 220,000. However, even as the industry declined the numbers of retired or working miners in the area remained high, and by 1988 there were estimated still to be 220,000 retired or working miners in the area. Lens, Liévin and Béthune were the towns at the centre of the Pas-de-Calais mining area. The last mine in the region, closed in 1990, was at Oignies, ironically the first Pas-de-Calais mine, which opened in 1842. As a result of mine closures the area has suffered serious economic decline with high unemployment.

1.4 Women working as coal sorters, Béthune area, with coal tub. (Authors’ collection)

Sugar beet

Of the other industries that developed in the area the one of most interest here is sugar production. The sugar content of beet was known in Germany from the middle of the eighteenth century and increased by selective breeding. It was near Arras, in 1810, that the first sugar in France was produced from sugar-beet. The inventor of the French industrial process, Jean-Baptiste Quéruel, developed the German technology. Along with his sponsor, the industrialist Benjamin Delessert, he was well rewarded by Napoleon, because of the shortage of West Indian sugar cane during the British blockade. As we will describe later the sugar refineries used narrow-gauge railways extensively. Nord-Pas-de-Calais is still a major producer of French sugar, providing one-fifth of the national total.

To produce sugar, the beet is washed and then shredded, and the sugar extracted with hot water. The raw juice is purified and condensed down and the sugar is then crystallised from the concentrated syrup. After extraction the beet strips are pressed to remove water and remaining sugar, and the waste (pulpe, pulp) can be used as animal feed. Frequently the whole process is carried out in one factory (sucrerie). In the area east of Arras after the First World War, the initial extraction was carried out in a râperie, and the juice was then transferred to a central factory for final sugar production (see chapter eight). Sugar beet can also be used to produce alcohol, in which case the factory is often called a distillerie.

Béthune

Béthune was a major centre with 14,000 inhabitants in the thirteenth century. It prospered as a textile producing town for the next several centuries. By the nineteenth century the population had reached half the modern...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Abbreviations

- Introduction

- Glossary of Railway and Related Words in French

- Chapter One: Introducing the Arras Sector and its Railways

- Chapter Two: The Metre Gauge Railway from Lens to Frévent and Related Lines and Tramways 1884 to 1914

- Chapter Three: The Metre Gauge Tramway from Béthune to Estaires and Related Lines and Tramways 1899 to 1914

- Chapter Four: Railways and Light Railways (60cm gauge) During the First World War (1914–1918)

- Chapter Five: Light and Metre Gauge Railways in the Arras Sector 1914 to 1918 North of Arras, First Army, later also Fifth Army

- Chapter Six: Light and Metre Gauge Railways in the Arras Sector 1914 to 1918 Arras and South of Arras, Third Army

- Chapter Seven: The Departmental Light Railways (60cm gauge) 1919 to 1925

- Chapter Eight: The Vis-en-Artois 60cm Gauge System 1926 to 1957 Société anonyme des chemins de fer à voie de 0.60

- Chapter Nine: The Metre Gauge Tramway from Béthune to Estaires and Related Lines and Tramways 1919 to 1932

- Chapter Ten: The Metre Gauge Railway from Lens to Frévent 1919 to 1948

- Chapter Eleven: The 60cm Gauge Railway from Lens to the Cité de Méricourt 1924 to 1939

- Chapter Twelve: Things to See and Do Now

- A Note on Archive Material

- Bibliography