- 348 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

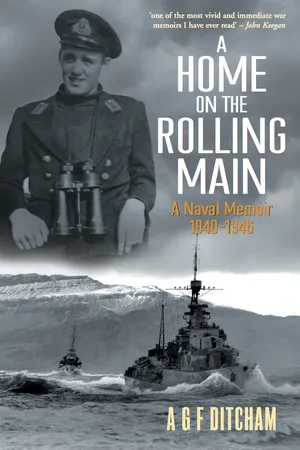

This WWII memoir of a Royal Navy Lieutenant offers a vivid account of maritime combat throughout the European Theater.

From first joining the Royal Navy in 1940 until the end of the campaign against Japan, Tony Ditcham was in the front line of the naval war. He served aboard the battlecruiser HMS Renown in the North Sea and Gibraltar. Serving on destroyers in most of the European theatres, he saw action against S-boats and aircraft off Britain's East Coast, on Arctic convoys to Russia, and eventually in a flotilla screening the Home Fleet.

During the Battle of the North Cape, Ditcham was one of the first men to actually see the German battleship Scharnhorst, and he vividly describes watching it sink from his position in the gun director of HMS Scorpion. Later his ship operated off the American beaches during D-Day, where two of her sister ships were sunk. En route to the Pacific Theater, his combat service ended with the surrender of Japan. Written with humor and colorful descriptive power, Ditcham's account of his incident-packed career is a classic of naval memoir literature.

From first joining the Royal Navy in 1940 until the end of the campaign against Japan, Tony Ditcham was in the front line of the naval war. He served aboard the battlecruiser HMS Renown in the North Sea and Gibraltar. Serving on destroyers in most of the European theatres, he saw action against S-boats and aircraft off Britain's East Coast, on Arctic convoys to Russia, and eventually in a flotilla screening the Home Fleet.

During the Battle of the North Cape, Ditcham was one of the first men to actually see the German battleship Scharnhorst, and he vividly describes watching it sink from his position in the gun director of HMS Scorpion. Later his ship operated off the American beaches during D-Day, where two of her sister ships were sunk. En route to the Pacific Theater, his combat service ended with the surrender of Japan. Written with humor and colorful descriptive power, Ditcham's account of his incident-packed career is a classic of naval memoir literature.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access A Home on the Rolling Main by A G F Ditcham in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Military Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PART 1

ALL AT SEA

Chapter 1

Scapa Flow

It was not a good start. May 4th 1940 and I was about to leave home on my first job. I was 17 and in my pocket was a Confidential letter ‘By Command of the Commissioners for Executing the Office of Lord High Admiral…’ telling me that I was a Midshipman, Royal Naval Reserve, and ‘directing’ me ‘to repair on board’ H.M.S. Warspite at Scapa Flow on 6th May. Warspite! A famous ship indeed.

The trouble was, the daily paper had just arrived, and on the front page was a small paragraph quoting from the press of Italy – then a neutral country. ‘Giornale d’Italia reports that H.M.S. Warspite and another battleship of the same class have arrived in Alexandria’.

‘Trust the newspapers to get it wrong,’ I said, my confidence in the Lord High Admiral remaining absolute.

The journey from Cheltenham to Scapa Flow was so difficult that it would indeed have been better to start from somewhere else. Fifty years later the route is unchanged and still involves changing trains at Gloucester, Birmingham, Crewe and Inverness. This includes the additional privilege of waiting at Crewe from 1030pm until midnight in order to catch the London sleeper to Inverness. Not that there were many sleepers in 1940. Not for the likes of me at any rate. A seat if you were lucky, and you might get to Inverness at 8am. Still 100 miles to go, to the top of Scotland, and the ferry to Orkney. But this 100 miles involves 1000 stops and took, and still takes, 3½ hours, dumping you at Thurso at 3pm. I reported to the Naval authority at Thurso.

‘The ferry for Orkney sails in the forenoon,’ they said. ‘Better stay the night in the Pentland Hotel.’ I had lots of money; my father had given me the huge sum of £5, and tomorrow I would be aboard Warspite earning 5/- per day. Of this, 2/6 would be diverted to pay for my keep, but that small fact had not yet registered.

Next morning, They spoke again; very friendly. ‘Sorry old boy. Afraid Warspite is not in Scapa. We don’t know where she is. You’d better go down to the Clyde and see if she is there. Here is a railway warrant.’ They were not allowed to know whereabouts of ships. Nobody was; but a call to the Admiralty would have elicited my fate.

I had spent 12 hours in the train already and did not relish going south again, exploring the Highlands. It was May, and a hot summer. Carrying my greatcoat, and with enough sixpences for porters with my two large suitcases, I set off.

I was in the train before I realised that ‘the Clyde’ was an indeterminate destination. Eventually I found the Naval Officer in Charge, Greenock.

‘Afraid she’s not here, old boy. See for yourself.’

So saying, and waving his arm at the view of the Tail-of-the-Bank anchorage. It was empty of any warship. They were all ‘occupying their business in great waters’ or were being repaired after damage in the course of the Norway campaign, which was still in full swing.

‘Better go down to the Admiralty and ask them what to do. Here is a railway warrant.’

A telephone call?

Back to Glasgow and the train south followed by porters, and distributing sixpences as I went. It was hotter still in London, and a cab took me, my greatcoat and baggage to the Admiralty. I eventually found the officer who actually knew about me and knew what to do. He was entirely unconcerned.

‘Oh yes, Warspite. I’m afraid she’s in the Med.’

I maintained a po-faced silence.

‘There are seven other midshipmen fresh from Dartmouth. They are in the same boat. Oh dear, sorry about the pun. They missed her too. We’ve sent them to Renown. You’d better join her, as well.’

A sinking feeling gripped me. ‘Where is she, sir?’ Please God, not Scapa Flow. Not that awful train again.

‘She’s at Rosyth, old boy. Here’s a railway warrant. Better stay the night here. Try the Regent Palace – it’s only about 7/6d a night.’

Another cab took me there, and I rang Cheltenham. My father, fondly imagining I was winning the war in the North Sea, answered the phone. ‘Good Heavens, boy, where are you?’

‘The Regent Palace Hotel.’ Recalling our farewells, Orkney-bound at Cheltenham six days before, this took some time to sink in. Could his son have made several cardinal errors already? I, of course, could not explain about ships’ whereabouts over the telephone.

Rosyth, at least, was only about half way to Orkney, which was a distinct improvement. I should soon be aboard my first sea-going ship, I could unpack, and settle, and learn my trade. By now it was May 11th, and the train rattled me back northwards in fine style. Then over the Forth Bridge to Rosyth station. A cab took me down to the dockyard and to the dry dock. The cabbies knew where each ship was lying, even if the naval authorities did not.

There was the mighty Renown in the dry dock, all 32,500 tons of her; only her upperworks, 15 inch gun turrets, and streamlined funnels showing. I had yet to learn the sailors’ mocking refrain:

‘Roll on the Nelson

The Rodney, Renown

This one funnelled bastard is getting me down.’

On the quarterdeck were some very important looking officers, topheavy with gold braid. I stood on the dockside, rooted to the spot with shyness and nerves. I would be there now, were it not for the cabbie who grabbed my bags, and strode across the gangway as if he were the Admiral. I followed, saluted the quarterdeck and reported to the Officer of the Watch. Suddenly, I felt at home. It was only six weeks since I had passed out of the Worcester and the simple act of saluting the quarterdeck was familiar routine.

‘Ditcham, Sir, come aboard to join.’

At this moment a tall bearded Lieut. Commander detached himself from the group further aft and bore down on us. He addressed himself to the Officer of the Watch, as I was of no importance.

‘Has the Midshipman come aboard to join?’

‘Yes, Sir.’

‘Well, send him away. All the midshipmen are on leave.’ So saying he disappeared.

In despair I turned to the Officer of the Watch.

‘Must I go on leave, Sir? I have spent the last week in the train.’

With this question I made history. During the period 1914-1918, and from 3 September 1939 to date, no one of any rank in any service had ever demurred at being sent on leave.

‘Well, I suppose you don’t have to go. Trouble is, the gunroom and chest flat1 are being repaired. Scharnhorst put a neat 11-inch hole through them last month. You will have to find somewhere to sling your hammock, and feed in the wardroom.’

‘What about the officer with the beard?’

‘Lt. Comdr. Holmes. He is the Gunnery Officer. He won’t mind. Just keep out of his way.’

For the next few days, I kept out of everyone’s way. That first evening, though, I went nervously into the wardroom to dine, and tried to be unobtrusive. Almost at once I was joined by Lt. Comdr. Holmes and his wife.

‘I thought I told you to go away’ he said, with a broad grin. ‘Have you met my wife?’

I was to see a great deal of him in the months that followed.

A ship ‘in dockyard hands’ is not very comfortable, especially in dry dock. One has to use the heads and ablutions on the dockside, and the yard cannot/will not provide sufficient power for lighting, heating etc., so the ship is gloomy to boot.

One way of avoiding my elders and betters was to explore the vast ship so that I should be able to find my way when directed to go somewhere at the double. While thus engaged in the dimly-lit ship, I found myself confronted by eight brass buttons. Looking left and right, I saw four stripes of gold braid on each sleeve. There was only one man with as much braid as that. I had run into the Captain. I looked up into a benign, beaming, ruddy face with grey curly hair beneath his cap. Nobody had told me that Capt. Barrington Simeon stammered.

‘A-and who-who are you?’

I explained.

‘So-ho you are a Woos-hooster boy, are you? Well, so-ho am I. So-ho be-hay-have yourself.’ With a smile he was gone.

The midshipmen and sub-lieutenants lived in the gunroom and kept their gear in chests of drawers bolted to the deck in the chest flat. Each of us slung his hammock above his chest. These two ‘spaces’ or ‘rooms’, were the last two in the stern of the ship, except for the ship’s chapel which took up the narrowing pointed stern end of the ship. So the chest flat was periodically a passageway for any of the 1800 men of the ship’s company on the way to communion. This would only hold about 40 men and attendance was voluntary, as distinct from ‘church parade’.

Leading out of the chest flat was a bathroom with 3 baths, designed for the peacetime complement of 18 gunroom officers. My arrival brought the total to 36, 29 midshipmen and 7 sub-lieutenants. The bath water was heated almost instantly by a squirt of super-heated steam piped from the boiler rooms. The bath water was expelled below the water line by doing something clever with the steam pressure. It was quite simple really, but it was not unknown for a simple midshipman to open the right valves in the wrong order, and flood the bathroom and perhaps the chest flat, before the error was discovered.

H.M.S. Renown at speed in dirty weather.

It had been April 9th at 0337 when Renown had encountered Scharnhorst and Gneisenau in a blizzard west of Narvik. They fled with Renown in hot pursuit, and Scharnhorst was soon hit by a 15-inch shell. The Gunnery Officer was so surprised that instead of ordering ‘Rapid Broadsides’, he exclaimed ‘Good God, we’ve hit her!’ This he told me himself, several months later. The sequel to this story occurred a further three years on.

The German ships escaped, and Renown took stock. No one knew that Scharnhorst had sent an 11-inch armour-piercing shell straight through the wardroom and out through the chest flat on the waterline. (Fortunately the plating, which it penetrated, was too thin to explode it.) In due course, Capt. Barrington Simeon was told that the midshipmen’s chest flat was flooded. He was not amused.

‘Those blood-huddy midshipmen – they got the steam-heam valves wrong again.’

In the wild weather prevailing, it was some time before they realised that the midshipmen’s uniforms were washing out of the 11-inch hole leaving a trail from Narvik to Scapa Flow. End of digression.

Back to the 15th May, on which day the ship’s company returned from leave, and I met my fellows of the gunroom. At the other end of the scale, Vice-Admiral Jock Whitworth returned. He commanded the 1st Battle Cruiser Squadron, comprising Renown and Repulse, plus attendant cruisers and destroyers. His ‘short title’ was therefore B.C.1. The only other battle cruiser, Hood, was the flagship of Force H wearing the flag of Vice-Admiral Somerville, and based at Gibraltar.

It was Jock Whitworth, who, in the middle of the North Sea, had shifted his flag, by means of a seaboat, from Renown to the even more powerful Warspite, and barged into Narvik fjord sinking every ship in the fjord – mostly large fleet destroyers, from which the German fleet destroyer command never fully recovered; thus the second Battle of Narvik.

During the Great War, there had been three Battle Cruiser Squadrons, comprising the Battle Cruiser Fleet, commanded by David Beatty. His flagship Lion led the 1st B.C.S., as well as the B.C.Fleet. This idiosyncratic officer defied the uniform regulations by designing his own uniform jacket with six buttons instead of eight. There is a famous photo of him thus attired pacing his quarterdeck with King George V.

Beatty’s uniform led the gunroom officers of the 1st B.C. Squadron to leave the top button ...

Table of contents

- Front Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- CONTENTS

- Foreword

- PROLOGUE

- Part One – ALL AT SEA

- Foreword to Part Two

- Part Two – TWO YEARS HARD

- APPENDICES

- GLOSSARY

- NOTES