- 400 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Naval Anti-Aircraft Guns & Gunnery

About this book

A winner of the Samuel Eliot Morison Award for Naval Literature gives "an excellent overview of the problems involved in shooting at airplanes from ships." (

Coast Defense Journal).

This book does for naval anti-aircraft defense what the author's Naval Firepower did for surface gunnery—it makes a highly complex but historically crucial subject accessible to the layman. It chronicles the growing aerial threat from its inception in the First World War, and the response of each of the major navies down to the end of the Second, highlighting in particular the widely underestimated danger from dive-bombing.

Central to this discussion is an analysis of what effective AA fire-control required, and how well each navy's systems actually worked. It also takes in the weapons themselves, how they were placed on ships, and how this reflected the tactical concepts of naval AA defense. Renowned military historian Norman Friedman offers striking insights he argues, for example, that the Royal Navy, so often criticized for lack of "air-mindedness," was actually the most alert to the threat, but that its systems were inadequate—not because they were too primitive but because they tried to achieve too much.

The book summarizes the experience of WW2, particularly in theaters where the aerial danger was greatest, and a concluding chapter looks at post-1945 developments that drew on wartime lessons. All important guns, directors and electronics are represented in close-up photos and drawings, and lengthy appendices detail their technical data. It is, simply, another superb contribution to naval technical history by its leading exponent.

This book does for naval anti-aircraft defense what the author's Naval Firepower did for surface gunnery—it makes a highly complex but historically crucial subject accessible to the layman. It chronicles the growing aerial threat from its inception in the First World War, and the response of each of the major navies down to the end of the Second, highlighting in particular the widely underestimated danger from dive-bombing.

Central to this discussion is an analysis of what effective AA fire-control required, and how well each navy's systems actually worked. It also takes in the weapons themselves, how they were placed on ships, and how this reflected the tactical concepts of naval AA defense. Renowned military historian Norman Friedman offers striking insights he argues, for example, that the Royal Navy, so often criticized for lack of "air-mindedness," was actually the most alert to the threat, but that its systems were inadequate—not because they were too primitive but because they tried to achieve too much.

The book summarizes the experience of WW2, particularly in theaters where the aerial danger was greatest, and a concluding chapter looks at post-1945 developments that drew on wartime lessons. All important guns, directors and electronics are represented in close-up photos and drawings, and lengthy appendices detail their technical data. It is, simply, another superb contribution to naval technical history by its leading exponent.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Naval Anti-Aircraft Guns & Gunnery by Norman Friedman in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Military & Maritime History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER 1

AN EVOLVING THREAT

Unlike surface gunnery, anti-aircraft gunnery developed in the context of a rapidly-changing threat. There were also changes in the way in which navies evaluated the air, compared (say) to the surface, threat. There was already an air threat in 1917–18. The Germans and the British both used torpedo bombers in combat, and the British considered reconnaissance Zeppelins a major problem in the North Sea.1 Aircraft were prominent enough in anti-submarine warfare that some submarines were given heavy anti-aircraft guns. When the Royal Navy reviewed the situation in 1931–3, its Naval Anti-Aircraft Gunnery Committee cited the rise of ship-based aircraft in the US, British and Japanese navies, French flying boat operations over the Mediterranean, and the impressive mass Italian long-range flights (mainly led by Italo Balbo: the formations were often called ‘Balbos’).

Air Arms

The US Navy and the Imperial Japanese Navy both had their own air arms during the inter-war period. The US Navy became particularly air-minded. It created an instant corps of senior naval aviators by requiring all commanders of naval aviation activities and ships (including carriers) to have either ‘wings’ or aviation observer status. Ambitious officers sought the necessary training and gained an aviation perspective. The United States also created a large naval air arm, which it demonstrated to itself in the annual Fleet Problems (fleet exercises) in the Pacific. The Fleet Problems and also nearly compulsory senior officer education at the Naval War College (where the students worked out phases of the war plan against Japan) educated even non-aviators in the impact of naval aviation. For example, after one Fleet Problem in the late 1930s, the main complaint of the battleship officers was that the carriers had fought what seemed to be a private war, denying them the air services, including fighter cover, they wanted. Rear Admiral Ernest J King (Commander, Air Squadrons, Battle Force and later wartime Chief of Naval Operations) pointed out that the carriers could easily destroy each other. If they did not fight their ‘private war’, the battleships would never have any air services, because all the aircraft would be on the bottom. Typically US carriers operated well away from the battle line, which was easily spotted at a distance, in order to make it more difficult for enemy scouts to find them. That contrasted sharply with contemporary British thinking. King’s insight, which probably was widely understood, emphasised the need for anti-aircraft weapons, because at times the fleet would have to defend itself.

In support of the carrier vs. carrier war, in the late 1930s the US Navy decided that its dive bombers would have an alternative role as scouts; they were therefore designated in an SB series, as in the SBD Dauntless. US carriers typically had four squadrons on board: one of fighters, one of dive bombers, one of scouts, and one of torpedo bombers. Until the advent of radar, there was little hope that the fighters could effectively protect the carriers, which operated singly. The fighters were intended more as strike support, helping the strike aircraft deal with any defending fighters and probably also helping by strafing enemy air defence control and guns.

The pre-war Imperial Japanese Navy also had a large carrier force. Unlike the US Navy, the Japanese followed the Royal Navy (see below) in equating carrier aircraft capacity with hangar capacity.2 Typically their carriers had three rather than four squadrons on board. That is why the three US carriers at Midway had about as many aircraft as the four Japanese carriers they faced and defeated. On the other hand, in 1940–1 the Japanese succeeded in creating multi-carrier Air Fleets which could fight as single entities. Overall, they had little faith in air defence: enemy carriers had to be destroyed before they could strike. The Japanese depended mainly on fighters rather than on shipboard antiaircraft guns for fleet defence. However, they appear not to have appreciated the importance of fighter control, e.g. to keep fighters from being drawn entirely to counter one raid while another might be approaching. For them, Midway was an object lesson in just such failure: the defending fighters were drawn down to deal with the US torpedo bombers leaving the way open for the dive bombers. Without radar and also with poor voice radio, fighter control was impossible.

Like their US counterparts, Japanese cruisers carried floatplanes assigned to scouting as well as spotting duties. In the US Navy, the floatplane scouts were intended for use when the cruiser or cruisers operated independently, far from the fleet. Unlike the US Navy, the Japanese used these same floatplanes to scout for carriers screened by the cruisers, as at Midway. Wartime US and British observers considered that the problems of tracking enemy fleet units and of coaching a strike force into position had received particular attention in the Imperial Japanese Navy.3 Scouting was considered so important that, unlike the US Navy, the Japanese separated it from strike, to the extent that scouts were ordered to avoid combat if possible so that they could complete their scouting missions. The fleet scouting mission was symbolised by the design of the Tone class cruisers, with their open aircraft areas aft. Only during the war did the Japanese develop a specialised high-performance carrier scout, the C6N1 Saiun.4 It had no Western equivalent. Wartime Japanese air tactics envisaged a scout or snooper working with a strike force, using elaborate tracking and liaison techniques. By 1943–4 Japanese scouting aircraft had radar. They were advised to minimise both radar and radio transmissions until the moment came to home the strike force on the target, at which time there had to be a considerable volume of traffic to and from the tracking aircraft. On this basis communications volume became a reasonable indication that a striking force or a relief shadower was being homed on the target.

Twin Mk XVI guns on a Mk XIX mounting, from the 1945 Gunnery Pocket Book. The fuse-setting machine on the left has been omitted for clarity, as has the divider between the guns. (Photograph by Richard S Pekelney, Historic Naval Ships Association, courtesy of Mr Pekelney)

Close-Range Weapons

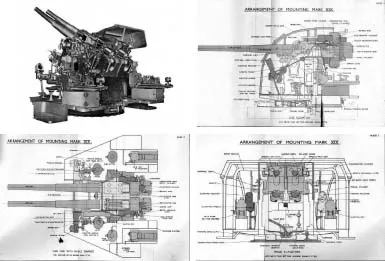

Smaller guns were also needed. In an 11 February 1920 memo, the Naval Anti-Aircraft Committee recommended development of a multiple pom-pom to deal with low-fliers attacking with torpedoes and explosive boats controlled by aircraft.53 The mounting should be director-controlled. The committee proposed that Chatham Dockyard cut down the mounting of the standard 11in anti-submarine howitzer to take six 2pdr pom-poms spaced 3ft apart, the original training gear being retained but modified for director control. Guns should be arranged so that their lines of fire could be made to diverge to fill a desired area with projectiles (the committee thought the natural inaccuracy of the gun, which should be tested at ranges up to 3000 yds, might suffice to give the desired coverage). The Director of Naval Construction calculated that an Inconstant class cruiser could take one mounting in place of one set of torpedo tubes, with little modification. The cruiser’s director could be set up to control the gun mounting.

Trials compared 2pdrs and 3pdrs to decide which was the smallest (for maximum rate of fire) sufficient to defeat a torpedo bomber with one hit. Either was enough if it hit the engine, fuselage, or wings inboard of the outer struts; neither would suffice if it only hit the outer wings. The 3pdr offered a slightly greater chance that a fragment would hit the aircrew even if a direct hit on the outer wing failed to crash the bomber.54 That was not enough to disqualify the 2pdr.

Maximum acceptable weight for the multiple mounting was set at that of the 3in HA gun which then armed destroyers: 2 tons 12 cwt.55 Rate of fire was to be not less than 60 rounds per minute per barrel. Director control would be exerted by the usual follow-the-pointer technique, the mounting being moved by a continuously-running electric motor which the crew could clutch in and out. The mounting should elevate and train at 15°/sec, with a maximum elevation of 45° (as yet there was no vertical-diving threat) and a maximum depression of 15°. As usual, both Vickers and Armstrong (Elswick) were asked to design mountings. Armstrong’s, which was designed for continuous rather than burst fire, was rejected as too complex, and a mock-up of the Vickers mounting was examined at Vickers in July 1923. Rate of fire was better than required (90 rounds per gun per minute) and maximum elevation was 80° rather than 45°. Rate of fire was 90 rounds per barrel per minute, compared to the required 60. The prototype mounting passed its shore trials in 1927 and it was successfully tested on board Tiger in 1928.

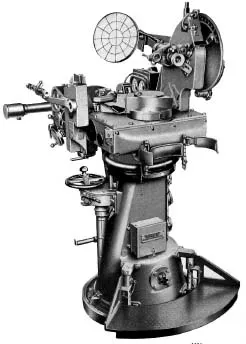

The initial pom-pom director was a simple dummy gun, the virtue of which was that it removed the aimer from the noise and vibration of the mounting. This is the Mk II version. The straps allowed the single operator to turn the director with his body. The cartwheel sight made it possible to estimate deflection. Mk II can be compared to the slightly later US Mk 44, which was also a very simple non-computing director.

The most important British automatic weapon developed before the Second World War was the multiple pom-pom. This octuple one was on board Shropshire. The photograph is supposed to date from 1942–4, but note that the gun mounting is entirely unshielded, and that it is unmanned while it is being loaded. These guns were poweroperated, which is why Prince of Wales suffered so badly as soon as she lost power. (State Library of Victoria)

The quadruple pom-pom was designed specifically for destroyers and cruisers; this one is aboard the destroyer hmas Napier. This version had separate layer and trainer, and each had his own computing sight, presumably a US-supplied Mk 14. Note the splinter shield in front of the mounting and also the protection for the ammunition belts. (State Library of Victoria)

Like Mk II, it fired existing 2pdr ammunition, large quantities of which remained after the First World War. That limited it to a muzzle velocity of 1900ft/sec, which by the late 1930s was clearly insufficient. The first operational mountings were ordered under the 1930–1 Estimates: twelve Mk M octuple mountings and six directors.58 The initial eight-barrel version was designated Mk M and later Mk V.59 During the 1930s a modified Mk VI mounting was ordered; it was standard during the Second World War.

By 1927 it had been decided that rounds should all be HE with sensitive-enough fuses to burst when hitting the fabric of an aircraft. Since the shell would not make a visible burst unless it hit, a proportion of ammunition had to be tracers. For initial trials the prototype mounting was connected to an Adventure-type director. Based on earlier trials in the cruiser Dragon, it was thought that a single control officer could lay and fire the mounting and also spot, but that proved to be too much for one man. A target moving almost directly at the mounting was relatively easy to hit, but it was much more difficult to hit a target with a high crossing speed; at any great range tracers gave a misleading impression. Spotting would have been easier if shells had been time-fused, bursting at the expected range. However, that would have required an automatic fuse-setter, an unacceptable complication.

Within a few years the Royal Navy considered several alternative ways to aim light anti-aircraft guns. Eyeshooting, which it eventually much favoured, had the gunner visualise the future position of the target and point at it using either a telescope or a forward area sight (an open sight). He might base aim on an estimate or he might use a telescope supported by some form of rate estimation. Any such method had to allow the gunner to override and select an alternative point of aim if the aircraft manoeuvred. Alternatively, course or speed sights could be set by a control operator for inclination, dive, and speed during an attack.

An alternative was hosepiping. No sights were used, the gunner relying on tracers to mark the trajectory of his rounds. In effect he was moving a hose of tracers. He relied on this visual aid to bring the trajectory onto the target and to keep it there. Lewis gunners used hosepiping because at very close range (500 yds and less) it was as efficient as eyeshooting and required less skill. To support it, the usual proportion of tracers was one to four rounds of ball in a Lewis gun.

The key argument favouring high muzzle velocity was that the target was not brought under fire until the time of flight of the initial rounds elapsed. If it jinked, it could not be brought under fire until another time of flight interval elapsed. In 1936 the DNO wrote that ‘from the control point of view reduction of time of flight is more important than any other single factor’. Time grew shorter and shorter as aircraft performance improved sharply through the 1930s.60

By 1928 Elliott Bros. was working on a prototype director. It was a simple sight on which allowance could be made for own speed, for the speed and course of the target, and for tangent elevation (range). The sight was laid and trained by one man, and data would automatically be sent to the mounting. It was understood that the weapon was intended mainly to defeat torpedo bombers. They placed themselves in a vulnerable position by flying low and straight for at least 15 to 20 seconds before releasing their torpedoes. That raised a problem. If the gun opened at excessive range it was unlikely to hit, but it might easily exhaust too much of the ammunition in a belt. Yet tracers had to be expended in order to tell that aim was correct for line, before the bomber settled down into its final run. DNO recommended firing a short burst (to establish line) at 2000 yds, then holding fire until about 1500 yds. By 1933 experience showed that to achieve 70 per cent hits it was necessary to know the range within 200 yds, inclination within 10...

Table of contents

- FRONT COVER

- TITLE PAGE

- COPYRIGHT PAGE

- CONTENTS

- ABBREVIATIONS

- ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- INTRODUCTION

- CHAPTER 1 AN EVOLVING THREAT

- CHAPTER 2 MAKING ANTI-AIRCRAFT FIRE EFFECTIVE

- CHAPTER 3 BEGINNINGS

- CHAPTER 4 THE INTER-WAR ROYAL NAVY

- CHAPTER 5 THE INTER-WAR US NAVY

- CHAPTER 6 THE INTER-WAR IMPERIAL JAPANESE NAVY

- CHAPTER 7 OTHER EUROPEAN NAVIES BETWEEN THE WARS

- CHAPTER 8 THE ROYAL NAVY AT WAR

- CHAPTER 9 THE US NAVY AT WAR

- CHAPTER 10 AXIS NAVIES AT WAR

- CHAPTER 11 POST-WAR DEVELOPMENTS

- NOTES

- BIBLIOGRAPHY

- APPENDIX: GUN DATA