![]()

Chapter 1

Nineteenth-Century Liners

For most of the nineteenth century people were on the move in the greatest migration ever seen. Many were escaping poverty in their home countries whilst others were seeking their fortune in the gold rushes of North America, Australia and South Africa. Communications around the world were also rapidly improving with the introduction of railways, the opening of the Suez Canal, a universal postal system and, most importantly, the laying of undersea telegraph cables. Tourism as we know it took off in the 1870s and 1880s. For the first time in many years there was peace in Europe with the ending of the Franco-Prussian War between France and Germany. Italy and Germany became unified nations in 1861 and 1871 respectively. This was also a time of colonial expansion which would see Britain establishing the world’s largest empire. To meet the demand, passenger ships became increasingly important throughout this period with great advances being made not only in ship design but also marine engineering.

The first steamship line on the North Atlantic

The first steamship line to be established on the North Atlantic was not Cunard Line. It was the British and American Steam Navigation Company which had been formed in 1835 by an ambitious London-based American entrepreneur, John Junius. He saw that the future of Atlantic travel lay not in sail but in steam-powered ships which could halve the average westbound crossing time of over a month. A 1,862gt paddle steamer was ordered from the London shipyard, Curling & Young. Laid down as Royal Victoria, her maiden voyage in 1838 was delayed because the engine builders went bankrupt. With the imminent arrival of Isambard Kingdom Brunel’s 1,320gt Great Western, British & American was determined to be the first into New York and chartered the small Irish Sea passenger ship Sirius (1837/703gt), shown below. Despite rough weather and limited coal supplies, Sirius arrived in New York on the morning of 23 April 1838, a few hours before Great Western. This event had a profound impact and one commentator wrote ‘there can be little doubt that ere long the Atlantic will be aswarm with these sea monsters and that a complete revolution will be wrought in the navigation of the ocean, as has already been witnessed on the rivers and inland seas’. How right he was. Within two years, the British postal system had been revolutionised with the introduction of the Uniform Penny Post and more importantly, the awarding by the Admiralty of subsidised mail contracts. These led to the formation of Britain’s leading shipping lines, including P&O, Royal Mail Line, Pacific Steam and Cunard Line. At a stroke, the world had become a smaller place with a faster and reliable postal service. Instead of months waiting for the mails, they would arrive in a matter of weeks.

Brunel’s ‘Greats’

Although Great Western was the first steamer constructed for service on the North Atlantic she was, like all three of Brunel’s ships, a one-off. His second ship, the 3,270gt Great Britain, below, was completed in 1843. She was not only the first screw-propelled passenger ship but also the first built of iron to cross the Atlantic. The largest ship in the world at that time, she was built at Bristol by Messrs William Patterson and Sons. With accommodation for 252 passengers, she was fitted with six masts and carried around 1,700 square yards of sail. Unfortunately this innovative vessel was a failure as she did not have a running mate so operating a regular service was problematic. Samuel Cunard, on the other hand, took a more cautious approach for his Liverpool to Halifax passenger-mail service with his fleet of four small, 1,100gt wooden paddle ships. The company’s first ironhulled, screw-driven ship, Andes (1,275gt), only appeared in 1852. Meanwhile Great Britain stranded on the coast of Ireland in 1846 but was refloated the following year. She was subsequently sold and operated as an emigrant ship to Australia. She eventually became a sailing ship and in 1886 arrived at Port Stanley in the Falkland Islands where she was used as a coal hulk. In 1970 she was returned to Bristol aboard a large floating barge. She has now been fully restored to her former glory as a museum ship.

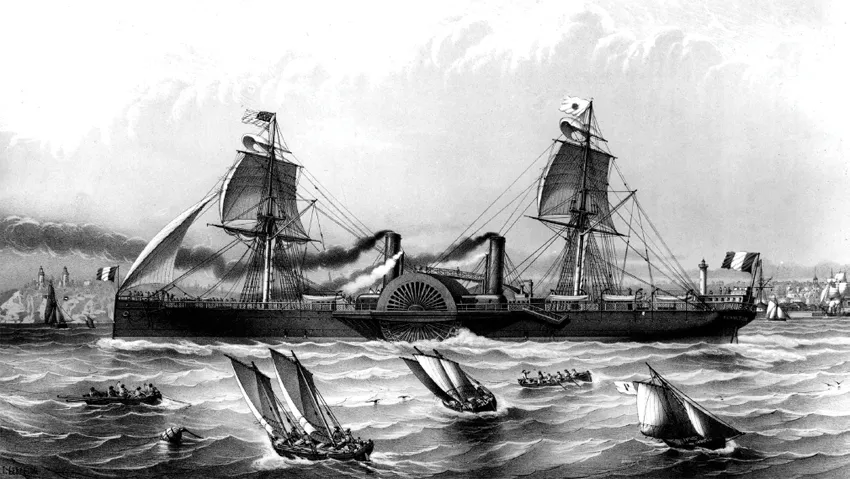

Brunel’s third ship was even more astonishing than his earlier ships. The 18,915gt Great Eastern was five times the size of any ship built to that date. Her record tonnage was not exceeded for another forty-three years. Designed for the Indian and Australian passenger and cargo trade she was completed on the Thames by John Scott Russell and Co. in 1858. Her four-year construction was a logistical nightmare and contributed to Brunel’s early death. She was also unique in the fact that she used both paddle wheels and screw propulsion and was able to do 14 knots. She had five funnels, six masts with sails and could accommodate 800 first, 2,000 second and 1,200 third class passengers. First class was sumptuous, with rich wall hangings and mirrored bulkheads. The 63ft long, 47ft wide and 14ft high Grand Saloon had a balcony and gas-lit chandeliers. Some of the cabins also had baths with hot and cold running water. Although a failure as a passenger ship Great Eastern revolutionised the world in July 1866 when she successfully laid the first transatlantic telegraph cable. She was sold for scrap on the Mersey in 1888.

The last Atlantic paddle steamers

On the North Atlantic, where speed was very important, paddle power had the edge over propeller-driven ships. However, they were expensive to operate with a daily coal consumption double that of a screw steamer. Despite this, Cunard was determined to have the fastest ships on the Atlantic so prestige took precedence over cost. In 1862, the Robert Napier shipyard completed the 3,871gt Scotia, Cunard’s last paddle steamer. She was one of the finest ships built for the company up to that date, not only in terms of looks but also passenger comfort. In 1863 she made the fastest-ever Atlantic crossing in both directions. Her record from Queenstown to New York (eight days, three hours), averaging 14.5 knots, remained unbroken until 1872 whilst her New York–Queenstown record (eight days, five hours and forty-two minutes), averaging 14.2 knots, remained in place until 1867. She had space for 1,400 tons of cargo, 573 cabin passengers and 1,500 troops in case of war. She was only withdrawn from service in 1878. She later became a cable ship and was wrecked in Guam in 1904.

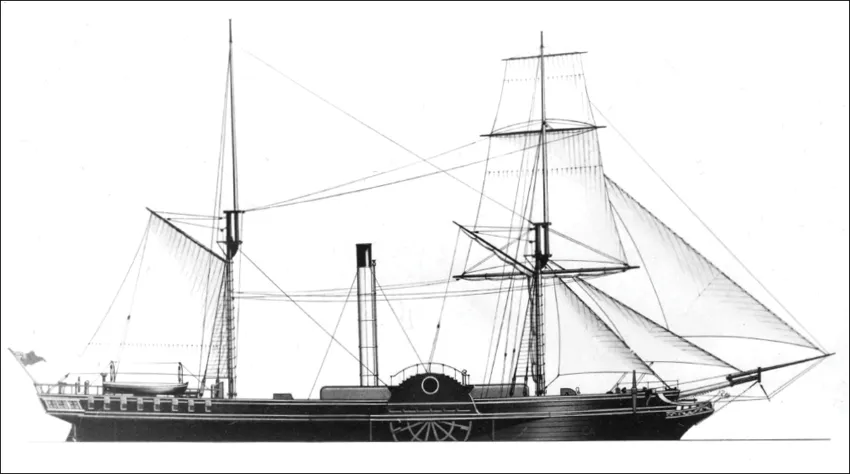

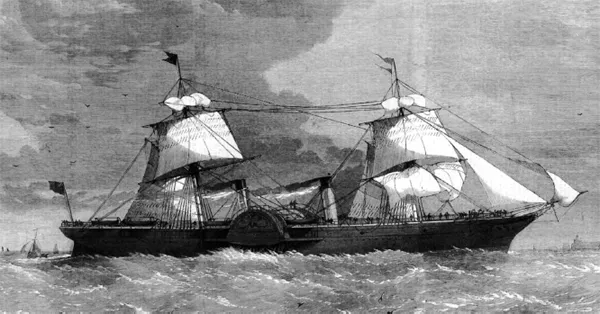

The newly-formed Compagnie Générale Transatlantique (French Line) was also committed to a fast transatlantic service and ordered nine paddle steamers for its new routes to the Caribbean, Mexico and North America. Three were built at Greenock by John Scott and Company. The first to be delivered in 1864 was the 3,204gt, 13-knot Washington, below, which inaugurated the Le Havre to New York service in June of that year. She was followed by Lafayette and Impératrice Eugénie. Impressive-looking ships with two tall funnels and twin masts, they each carried 330 passengers and 1,000 tons of cargo. However, their careers as paddle steamers were short lived as it soon became apparent that paddle propulsion was no longer a viable option. In 1867 Washington was converted to twin-screw propulsion and became the first Atlantic liner to be fitted with twin-screws. The remaining CGT paddlers also had their paddle power replaced with screw propulsion. Washington remained with French Line for thirty-six years and was only broken up in 1899.

Compound engines

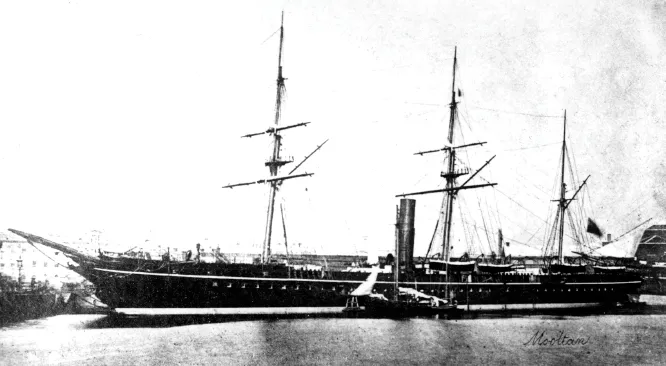

The development of the compound engine for screw-driven ships in the 1850s was one of the great advances in nineteenth century marine engineering. Although the single-cylinder expansion engine was easy to operate, it was a very inefficient use of steam power. The compound engine, on the other hand, allowed the steam to be passed from two cylinders of differing sizes without much loss of temperature and this not only provided better power, it also saved on the amount of coal used. Although coal was cheap and in plentiful supply, lower coal consumption meant smaller coal bunkers and thus more space for revenue-earning cargo. On longer routes operational costs were significantly reduced because they were not only able to travel further but also used less coal. Among the first companies to use these new engines was the Peninsular and Oriental Steam Navigation Company (P&O) which in 1840 had been awarded the mail contract to carry the mails between Southampton to Alexandria in Egypt and between Suez and Calcutta. This was later extended to Singapore, Hong Kong, Shanghai, Australia and Japan. Mooltan (1861/2,257gt) was the first to be fitted with an early type of compound engine which produced a speed of 12 knots. She was used on the Southampton to Alexandra service and carried 112 first and 37 second class passengers. In 1884 she was sold and reduced to a sailing ship and disappeared in 1891 whilst on a voyage from Newcastle upon Tyne to Valparaiso.

The first ship to cross the North Atlantic with a compound engine was the small 764gt steamer Brandon in 1854 whilst the first compound-engine passenger liner to operate on the Atlantic was Anchor Line’s 2,290gt India in 1869. Powerful compound engines also played a key role in the phenomenal success of Thomas Ismay’s Oceanic Steam Navigation Company Limited, commonly known as White Star Line, which commenced its service between Liverpool and New York in 1871 with the 3,707gt Oceanic, the first of a quartet of elegant 14-knot ships built at Belfast by Harland and Wolff. These four-masted ships were a revolution on the Atlantic with their extreme length and accommodation extended to the full width of the hull instead of the traditional narrow amidships deck-house. The main dining salon was also placed amidships where there was least motion and noise from the propellers. From the start, White Star Line’s main focus was passenger comfort in first class with larger cabins, steam heating, electric bells, taps for water, individual dining chairs instead of fixed, armless swivel chairs, and a dedicated smoking room. Oceanic carried 160 first and 1,000 steerage class passengers. The new White Star liners soon broke the Atlantic crossing records and during 1873, the average time for a Cunard Liverpool to New York voyage was almost a day slower than White Star. Oceanic’s name was passed to another White Star innovative liner in 1899, three years after the original pioneer ship was broken up.

The Suez Canal and the threat to P&O

The opening of the Suez Canal on 17 November 1869 was not only one of the most significant events in P&O’s history, it also posed a great threat. Although it was now able to operate ships all the way between ...