![]()

CHAPTER 1

The Channel Pilots

WHEN A SAILING SHIP came into the English Channel, her captain’s first priority, if bound for an English port or further afield through the Dover Straits, was generally to take on a Channel pilot. If she were bound for Le Havre or one of the other major French ports, a seeking Le Havre cutter would supply the captain’s needs. In today’s world of certainty about a ship’s position, electronic charts and the motor ship’s ability to steam in whatever direction seizes her navigator’s fancy, it may seem superfluous to pay a pilot in waters that start out over a hundred miles wide. This was not the case in times past.

![]()

Illustrated London News

In 1885 the popular London Illustrated News published this beautiful double-page spread of piloting activities. It is a spectacular achievement, showing at centre a cutter hove to in what might pass for the lee of an early steamship, launching her punt in a shocking sea so that the pilot can be rowed or sculled across. On the left, the pilot is burning his night-flare; at bottom right, the punt is away, and at top right, the pilot is boarding a windjammer in very much better conditions than the rest of the montage suggests.

(Author’s collection)

![]()

Channel tides can run at over 3kts in areas where neither coastline is visible, even in clear weather. A sailing ship beating her way in or out would sometimes find herself in tight quarters at the end of a tack, yet still be outside the pilotage area of any particular port. Even if she were not, it was perfectly possible that she would have missed the local pilot cutter and hence have no pilot when she desperately needed one. Finding his ship embayed on a strange coast in thick weather, a master would have given a month’s wages for the services of a competent expert who could recognise a misty glimpse of coast at a glance, or deduce his position from the depth and nature of the bottom as brought up by the armed leadline. Even today large ships, whose draught becomes a serious factor for safe navigation as the sea shoals towards Dover, take on Channel pilots as far west as Brixham, Devon.

In the case of British pilots who boarded in the Western Approaches, the term ‘Channel’ generally referred to all the channels between the islands of Britain as well as those separating them from the continent. Thus, a Channel pilot would be just at home taking a ship up to Greenock in Scotland as he would to the ‘Downs’ anchorage off east Kent, where ships bound to and from London waited for fair winds, or the approaches to Le Havre and Dunkirk. Even the Elbe in faraway Germany fell into his area of expertise. A Channel pilot boarding further up the English Channel itself, perhaps off Plymouth or certainly the Isle of Wight, was usually just what the term implied – a guide up the English Channel to the desired port pilot station. Once his ship arrived in the offing, the average Channel pilot would be content to hand over to the local man. Indeed, in later years he was obliged to do so by regulations. For London, this handover theoretically took place at Dungeness where a licensed Trinity House pilot would come aboard, but things didn’t always work out as the Elder Brethren of that redoubtable authority would have liked.

An outward-bound Channel pilot stranded far from home would be delighted to take a ship down to his local waters once more, thus securing a fee as well as a free ride. By unwritten but universal agreement, any ship he had brought up was his to take to sea, but this might entail a long wait and was by no means always adhered to. Before the railways, however, the land-based travel alternatives were unattractive in the extreme, and even in the days of steam they remained a poor economic substitute for a ship.

Channel pilots were experienced deep-sea sailors who had returned to home waters to take up a career in pilotage. Before the Merchant Shipping Act of 1872, there were no licences for their work. The only qualification for the job was that a man was able to do it and could convince a ship’s master that this was the case. A favourite device was to carry certificates or letters from satisfied masters and agents, but sometimes it was enough merely to step aboard from a pilot cutter and look convincing.

Some Channel men actually held an official licence for London as well as one or more for the many outports.As such, they were qualified to pilot a ship up to her berth. Outside of the Bristol Channel with its specific systems, many Channel cutters would be owned by a group of pilots offering a ‘one-stop shop’ service into the local port as well as the farther-ranging Channel pilotage up to London and beyond. After the 1807 Merchant Shipping Act which granted Trinity House jurisdiction over most of the Channel ports, the position of a Channel pilot was made clear; he could retain the part of the overall pilotage fee which concerned work outside the designated port limits to which his ship was bound. If a licensed port pilot took over for entry and berthing, he kept the rest. If no licensed port pilot presented himself, the Channel pilot could, like any other unlicensed pilot, keep the whole fee, so long as the master was willing.

![]()

Chart of the English Channel

This late nineteenth-century chart of the English Channel shows not only the topography, but also the highly significant tides that the Channel pilots knew so well. Even today, circumnavigating yachtsmen from relatively tideless waters baulk at entering the Channel because of the streams encountered here. Looking closely, we see 3kts in the Dover Strait, over 5kts north of Cherbourg and a spectacular seven in the Race of Alderney.

(From the Admiralty Tidal Stream Atlas, published 1899)

![]()

In 1872 a new Act of Parliament made provisions under which Trinity House availed themselves of the right to grant deep-sea licences to Channel pilots. Ever willing to extend their jurisdiction, the Elder Brethren of the corporation now began to examine candidates of proven sobriety, good conduct, five or more years’ sea service in addition to pilotage experience, and who were ‘sound in wind and limb’. The licences they issued provided their holders with kudos and an implied seniority in the event of a clash with another pilot. Being licensed also made it easier for a pilot to convince a captain that he was the man for the job, but Channel pilotage remained non-compulsory and the work was still open to unlicensed pilots as well as Trinity House men.

As was the case in other services when licences were first issued, there was hard feeling from established pilots who had been passed over, and a tendency from those who had been selected and had succeeded under examination – often by good fortune rather than any superior ability – to kick away the ladder by which they had climbed. This tension is illustrated by an article from the Shipping Gazette of 20 January 1880. It concerns itself with the loss of the Italian ship Erato.

The Erato boarded an uncertificated Channel pilot at Falmouth who was to take her to the Clyde. All went well as far as southeastern Ireland, but here the pilot ran her ashore on the Barrels near the Tuskar Rock. The article is eloquent in its defence of the ship’s master who took on the pilot in good faith, believing him to be competent on the strength of his professed recommendations. It goes on to state that the Court of Inquiry found the man ‘unqualified and ignorant of the navigation’ of the Irish Sea. Its conclusion was that while there may have been some unqualified pilots who were competent, there were certainly many who were not and that, were the Channels to be a compulsory pilotage area, all pilots would require certification and the problem would cease.

That this recommendation and its miraculous predicted outcome was held in low esteem by the majority of pilots is clear from a closing remark that, ‘while [they] are not required to hold licences – although they may do so, if they think it proper to prove their competency to the satisfaction of the Trinity House or other authorities – few of the men avail themselves of this privilege.’

![]()

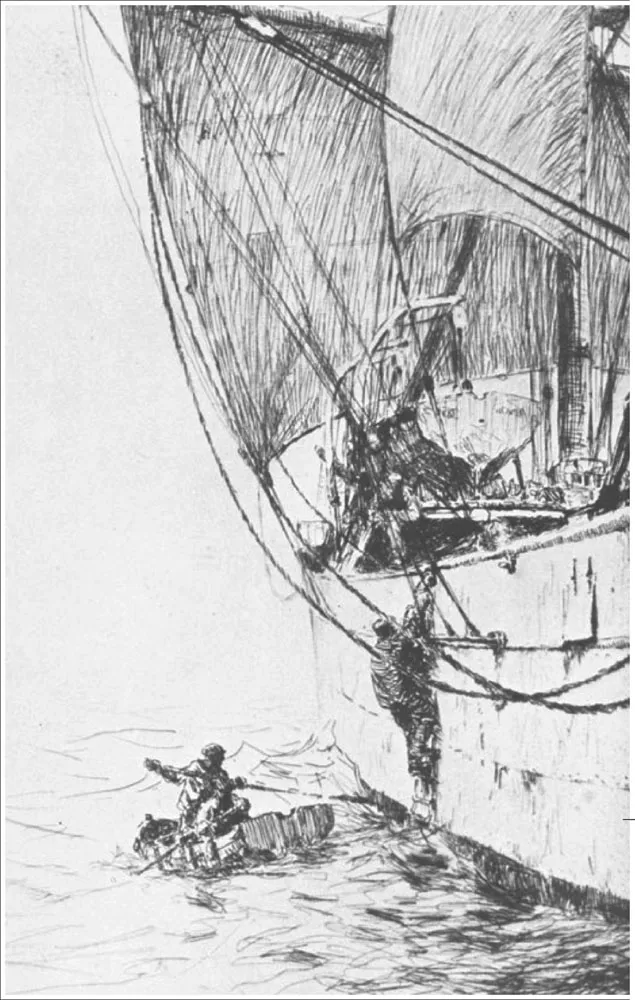

Boarding

A lovely drawing by Arthur Briscoe of the pivotal point of a pilot’s work, the actual moment of boarding. The man in the punt is fending her off with an oar as soon as his pilot has his feet firmly on the Jacob’s ladder. He now returns to the cutter and does not see his boss again until they meet up at some prearranged point at sea when the pilot brings another ship out, or in harbour when the cutter has chased this ship home.

(Private collection)

![]()

Bound up-Channel, a ship would, if she were fortunate, find her Channel pilot waiting west of the Isles of Scilly. If she failed to board a man here, her next landfall was likely to be the Lizard Point where a Falmouth cutter was generally cruising, often in company with one or two Le Havre boats ready to service anyone bound their way. Once east of the Lizard, a northbound ship could be lucky off Rame Head with a Plymouth-based cutter or, finally, the Isle of Wight. If she had still failed to take on a pilot by the time she passed the Nab Tower southeast of the Wight, she was probably on her own until she fell in with the Trinity House pilots off Dungeness, unless she first met up with a casual lugger from Deal cruising down-Channel in search of business.

![]()

CHAPTER 2

The Far West – The Isles of Scilly

STANDING ON THE Isles of Scilly on a summer’s day, it is hard to believe that one is on the outskirts of the English Channel. Were it not for the Cornish-style buildings, the colours of the shallow waters and sandy beaches could readily be taken for those of the tropics. The seas around the islands are a whirl of fast-running tides and straggling rocks, many of which will always remain unmarked. In the days of sail, and of steam prior to modern navigation systems, the toll they took of shipping was heavy and consistent, ranging from unknown trading schooners to the Royal Naval battle fleet under Admiral Sir Cloudesley Shovell, which famously ran ashore one nasty night in 1707.

There are a number of reasons for this, apart from the obvious one that the islands and their associated reefs lie athwart one of the main shipping routes of the world, at the confluence of the English, the Bristol and St George’s Channel leading northwards into the Irish Sea.

Early days

Until very recently, of course, all deep-sea navigation relied upon the captain obtaining a view of the heavens from which to fix his position. Any sailor who remembers those days can testify that the facts of life in the Western Approaches are such that this is by no means always available. Ships which had had no confirmation of their position for days thus had two choices: either go with the unpopular but safe option of heaving to until the sky cleared, or trust their dead reckoning and run in before the prevailing westerly weather. With crews who might have been at sea for months, it took a leader of strong moral fibre not to go for the soft choice and run in, hoping against hope to find a pilot. At night or in fog, things would be bad enough in themselves, but three further factors must be added to understand why even carefully estimated positions might well prove far removed from reality.

![]()

Cornwall and the Isles of Scilly

The Isles of Scilly lie approximately twenty-five sea miles from Land’s End. In the days of sail, they had enough trade in their own right to warrant a pilotage service, but it was as Channel pilots that the men of the islands excelled. Their dangerous, rock-bound fastness was strategically placed for boarding ships inbound to Great Britain or Northern Europe from the Atlantic, and hence from the whole world. Many a ship’s master was mightily relieved to be hailed by the Scillonian pilot cutter as he ran in, heart in mouth, perhaps having had no sight of the heavens for a fix for several days.

(From The Pilot’s Handbook of the English Channel, 1898)

![]()

The first of these is the Rennell Current, whose existence was not fully established until 1793. This sets northwest across the entrance to the English Channel and can reach aggregate speeds of almost 1kt, even when the tide has been allowed for. A ship approaching from the Atlantic without having obtained a fix for some days could therefore find herself many miles north of her dead reckoning position. There are instances of ships whose navigators imagined they were passing south of the islands only surviving stranding because they were so far off track to the north that when day dawned they found themselves proceeding up the Bristol Channel rather than the sea high-road to London.

The effects of the Rennell Current were aggravated before about 1750 by the inconvenient fact that the charted position of the islands (and the Lizard – the next landfall point) was anything from five to fifteen miles north of their actual location. Yet another nuisance to navigation at this period was that compass variation, changing steadily as it always has and always will, shifted from east to west. Within a few years, this rendered an uncorr...