- 160 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

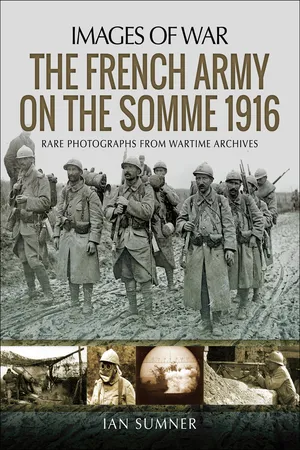

The French Army on the Somme 1916

About this book

So much has been written about the 1916 Battle of the Somme that it might appear that every aspect of the four-month struggle has been described and analyzed in exhaustive detail. Yet perhaps one aspect has not received the attention it deserves the French sector in the south of the battlefield which is often overshadowed by events in the British sector further north. That is why Ian Sumner's photographic history of the French army on the Somme is so interesting and valuable.Using a selection of over 200 wartime photographs, many of which have not been published before, he follows the entire course of the battle from the French point of view. The photographs show the build-up to the Somme offensive, the logistics involved, the key commanders, the soldiers as they prepared to go into action and the landscape over which the battle took place. Equally close coverage is given to the fighting during each phase of the offensive the initial French advances, the mounting German resistance and the terrible casualties the French incurred.The photographs are especially important in that they record the equipment and weapons that were used, the clothing the men wore and the conditions in which they fought, and they provide us with a visual insight into the realities of battle over a hundred years ago. They also document some of the most famous sites on the battlefield before they were destroyed in the course of the fighting, including villages like Gommecourt, Pozires, La Boiselle and Thiepval.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Chapter One

1914–1915

On the outbreak of war in August 1914, the Germans marched swiftly through neutral Belgium, before turning south to invade France. On the Somme, the French were driven back on both sides of the river: to the north, around Moislains, on 28 August; to the south, near Proyart, the following day. The fortress town of Péronne fell on the 28th, and the regional capital, Amiens, three days later, but within a week the German advance was halted by a Franco-British force at the battle of the Marne. The enemy withdrew, allowing French troops to reenter Amiens, but south-east of the Somme, on the river Aisne, the Germans managed to check Allied progress. Both sides then swung north again, each probing for a weakness, trying to turn their opponent’s flank in the series of leapfrogging movements subsequently named the ‘Race to the Sea’.

In late September, the two forces clashed again on the Somme in a second series of meeting engagements. South of the river, Allies and Germans fought each other to a standstill on the open Santerre plateau, between Chaulnes and Péronne, before switching the point of attack to the north bank, each vainly seeking the enemy’s open flank. With poor intelligence failing to pinpoint the exact position of the Germans, the French suffered a number of setbacks, every attempted advance provoking determined resistance and counter-attacks. On 29 September they captured but could not hold the village of Fricourt, 5km east of Albert, while successfully fighting off a German counter-attack designed to seize the town itself.

As the battle moved north towards Arras (Pas-de-Calais) and Ypres (West-Vlaanderen), neither side was able to win the upper hand, and to consolidate their gains the opposing troops began to dig in where they were. The next month brought a host of minor actions as the two forces struggled to seize small advantages of ground, but mutual exhaustion and shortages of ammunition quickly produced a stalemate. In mid-December, General Joseph Joffre, the French commander-in-chief, tried to break the deadlock by ordering an attack all along the front line, but bad weather and woefully inadequate artillery support doomed his initiative to failure. North of the Somme, around Mametz and Maricourt, on 17–18 December, the regiments of 53rd Division lost over 3,000 men yet scarcely breached the German wire; while 5km north-west, around Ovillers (now Ovillersla-Boisselle), the Bretons of 19th Infantry suffered 1,150 casualties with no greater success.

In 1915 and early 1916 the French sought to force a breakthrough by launching bloody and fruitless offensives in Champagne and, with British support, in Artois. The Somme, meanwhile, was considered a ‘quiet’ sector, as no large-scale operations took place here. Quiet, however, was a relative term. Scarred by their failed attempts to cross no man’s land, French and Germans alike were driven underground, seeking to dig tunnels beneath the opposing front line, explode a huge charge and exploit the opportunities thus created to seize sections of the enemy trenches. To counter the danger, both sides dug yet more tunnels, hoping to intercept the enemy and explode smaller charges (camouflets) to destroy his work. The Somme valley was too marshy for such operations, but the surrounding soft chalk downland provided ideal terrain. During the spring and early summer of 1915, mine and counter-mine were dug and exploded, followed by hand-to-hand fighting for control of the resulting craters: at La Boisselle, north of the river, seven main charges were set off by the two sides; south of the river, eleven French and twenty-one German mines were detonated at Beuvraignes, as well as sixty-seven French and thirty-four German mines and camouflets at Fay.

The only set-piece action took place on 7 June 1915, when the French Second Army mounted a diversionary attack in the far north of the sector, supporting the main Allied offensive in neighbouring Artois. Attacking across open, virtually flat terrain, the Second Army’s objective was to take the enemy trenches around Ferme de Toutvent, between the villages of Hébuterne and Serre. Despite heavy casualties the French achieved a tactical success, with the farm captured and held in the face of fierce German counter-attacks from 10 to 13 June; yet strategically the attack was a failure, lacking the overall strength to pull in the enemy reserves. Meanwhile every regiment involved suffered enormously: 64th Infantry, for example, lost 1,100 men during a week in the trenches at Hébuterne. Such was the scale of French losses – incurred here and in the main offensives in Champagne and Artois – that Joffre was compelled to take action. His allies were pressed to assume responsibility for more of the front line, and in August the newly created British Third Army moved into place, taking control of a 26km sector running south from Hébuterne as far as the Somme at the village of Curlu.

Marching infantry fall out for a break, September 1914. In the background, Algerian Tirailleurs press on. Mobilized in August in Nancy (Meurthe-et-Moselle), the men of 26th Infantry (XX Corps) had already seen action several times in Lorraine before a combination of trains and old-fashioned marching brought them to the Somme in late September. ‘The whole region was on fire,’ they discovered. ‘Albert, Fricourt, Mametz were in flames.’

The Germans march into shell-damaged Péronne, 29 August 1914. Writing under the pseudonym ‘Fasol’, local journalist Henri Douchet noted how quickly the enemy seized control: ‘the German occupation is reaching further and further across town, much to the annoyance of those premises, more numerous every day, grabbed by the Kommandatur’. By November Douchet was reporting that ‘all weapons and munitions in local hands must be deposited in front of the town hall … Anyone subsequently found with a weapon will be shot. Should any hostile acts [be committed], and particularly shots fired, while German troops are in residence, the town will be put to the torch.’

Both French and Germans created ad hoc regimental cemeteries during the ‘Race to the Sea’. Erected near Dompierre, this grave marker commemorates men of I Bavarian Corps: ‘Here Bavarian heroes rest in peace, fell 1914’. The département of the Somme now houses eleven German military cemeteries: the largest, at Vermandovillers, remembers 22,632 men; Fricourt, 17,031; and Rancourt, 11,422.

The Albert–Bapaume road passes through the village of Pozières, prior to the war. Positioned on a breezy ridge above the river ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Introduction and Acknowledgements

- Further Reading

- Chapter One: 1914–1915

- Chapter Two: The Plans

- Chapter Three: The Offensive Begins

- Chapter Four: Regaining Momentum

- Chapter Five: The End of the Offensive

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access The French Army on the Somme 1916 by Ian Sumner in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & European History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.