![]()

CHAPTER 1

Concepts and Techniques

In 1946, James Hornell, marine biologist by profession but nautical ethnographer-historian by inclination, published Water Transport, a remarkable volume that summarised his wide-ranging – almost worldwide – knowledge of working rafts and boats. In his preface, Hornell defined water transport as ‘the many devices upon which men, living in varying stages of culture, launch themselves afloat upon river, lake and sea’ Hornell’s ‘many devices’ may be divided into four classes: floats, rafts, boats and ships. For reasons of brevity, the term ‘ship’ is used in the title of this book. Nevertheless, for our purposes here, ships may be thought of as large boats; the three other classes may be distinguished, one from another, by considering how the buoyancy of each is derived or applied.

Floats are personal aids to flotation: a float’s buoyancy is applied direct to the man partly immersed in the water. Outside tropical waters, the seagoing use of floats is constrained by water temperature and limited by the endurance of the user.

Rafts derive their buoyancy from the flotation characteristics of each individual element which must have a specific density less than 1 (i.e. it must float). Some rafts are ‘boat shaped’, nevertheless they are ‘flow-through’ structures and are therefore not boats. Like floats, rafts are used on rivers and lakes but their ‘flow-through’ characteristic means that, outside the zones of warmer water (approximately 40°N to 40°S) their use at sea is limited and is, indeed, impossible when cold air and sea temperatures are combined with exposure to wind and/or rain to the point where the crew are disabled by hypothermia.

Boats derive their buoyancy from the flotation characteristics of a hollowed vessel as water is displaced by its watertight hull. There are no limitations on the specific density of hull materials, although those made of lighter materials will float higher in the water and therefore be able to carry greater loads.

Within these groups, sub-divisions may be recognised by reference to the principal raw material used. Thus there are log floats, hide floats, bundle floats and pot floats; rafts of logs, of inflated floats, of bundles and of pots; and boats of logs, bark, hides, pottery, reed bundles, coiled basketry (the latter two waterproofed by bitumen) and planks.

BOATBUILDING SEQUENCES

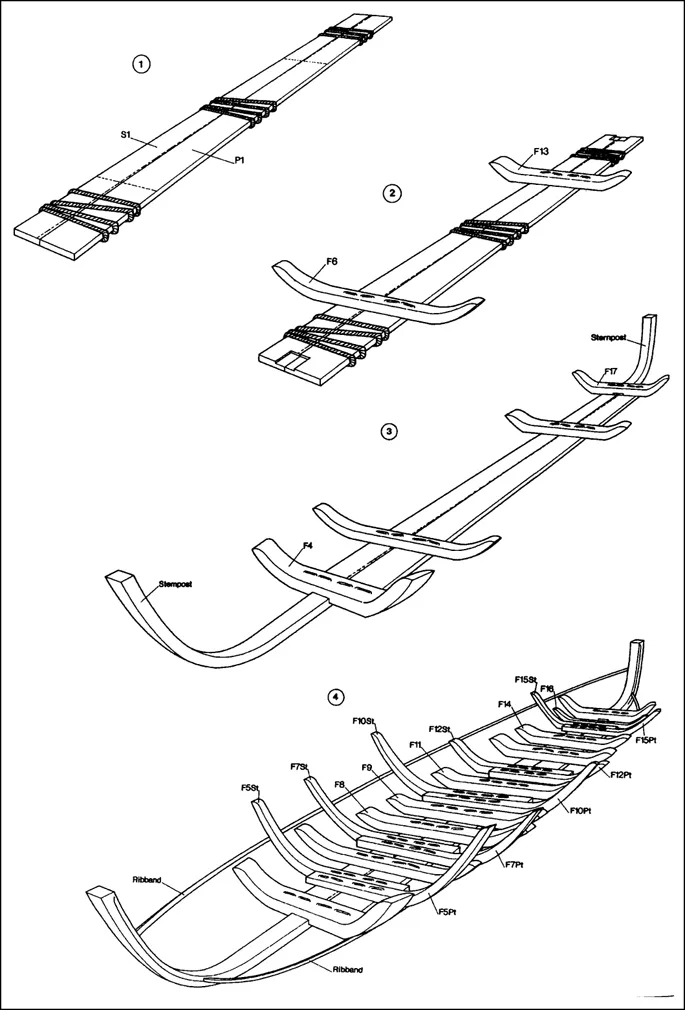

Several of those sub-types may be further partitioned depending on whether they are built as a watertight shell or as a waterproofed frame. Planked boats are either ‘plank-first’ (‘shell-first’ – Fig. 1.1) or ‘frame-first’ (‘skeleton-first’ – Fig. 1.2). In the former case, the watertight planking defines the shape of the hull which is subsequently strengthened by framing. In the second case the hull is defined by the framing which is subsequently made watertight by planking fastened to that framework.

Fig. 1.1 The plank-first sequence of building a boat. (after Crumlin-Pedersen)

Fig. 1.2 The first four stages in the frame-first sequence of building a boat.

Logboats are built ‘shell-first’. Bark boats are also generally built ‘shell-first’, but recently, in Sweden, British Columbia and Siberia, some (the larger ones?) were built by sewing or lashing bark pieces to a framework. Most hide boats are built skeleton-first; they are then made watertight by the addition of a hide cover. Small (‘one-hide’) boats in North America and in Mongolia, on the other hand, were built as a watertight shell (a ‘leather bag’) which was sometimes re-enforced by framing.

If hull planking is found fastened together (rather than to a framework) it is almost certain that such a vessel had been built in the ‘shell’ (plank-first) sequence. Exceptionally, however, there was a period in China (fourteenth to fifteenth centuries AD – and on to the twentieth century) when seagoing ships with planking fastened together had actually been built frame-first.

Although archaeologists identify these two different approaches to boatbuilding by determining the building sequence, early plank-boat builders would probably have thought of them as different ways of obtaining hull shape. In the plank-first case, shape was determined by eye, and visualised as a watertight shell of planking reinforced by framing. In frame-first building, on the other hand, shape was obtained by fashioning individual frames and setting them so that the required hull shape was outlined: such boats were visualised as a framework skeleton that was subsequently ‘waterproofed’ by planking.

BOATBUILDING TRADITIONS

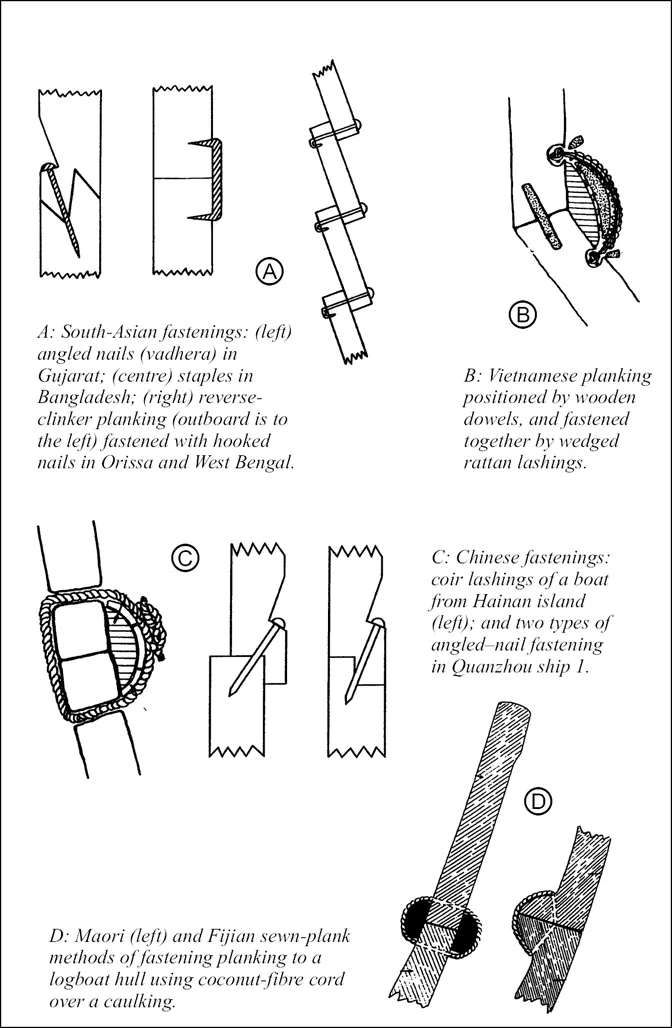

A ship- or boat-building tradition is an archaeological concept; it may be defined as ‘the perceived style of building generally used in a region during a given time range’. Such traditions were initially recognised by archaeologists using intuitive, ad hoc methods. As more wrecks were found, it proved possible to identify characteristics that seemed to define certain groups. An important, often diagnostic, feature is the type of fastening used in a boat, either to fasten planking together or to fasten planking to framework (Figs. 1.3 & 1.4).

Fig. 1.3 European fastenings.

Fig. 1.4. Plank fastenings used in India, Vietnam, China & the South Pacific.

The Nordic building tradition (Ch. 3) originated in the western Baltic in the early centuries AD and reached its climax during Viking times (eighth to eleventh centuries AD): some of its features continued to be recognisable in wrecks and illustrations dated as late as the fourteenth century. Other traditions had been given type names during late-medieval times: ‘cog’, ‘hulc’ and ‘carrack’, for example. Contemporary illustrations and descriptions allow us to link some of these type-names with excavated wrecks – there is now a sizeable group of vessels recognised as cogs. Other evident traditions, for which no type name has survived, have to be given a name: for example, the term, ‘Romano-Celtic’ is used to describe a group of second to fourth centuries AD, north-west European vessels (some seagoing, others river craft), with several characteristics in common.

It is not necessary that all vessels thought to be of one tradition should possess all characteristics. Each vessel in a tradition has to share a large number of characteristics with all others, but no one characteristic has to be possessed by all of them. Such groups are said to be ‘polythetic’, and, in not requiring uniformity, they reflect our intuitive understanding of the real world.

BOATBUILDING MATERIAL & TOOLS

Hides, reeds, and other materials – even pottery – have been used to build boats but, worldwide, timber is especially important, being the principal material for log rafts, log boats, and (pre-eminently) planked boats. Wood is also used for the framework of buoyed rafts, hide boats and reed-bundle boats, and for the lashings and sewing used to fasten together sewn-plank boats, hide boats and bundle rafts. Furthermore, wooden pegs (treenails) have been used widely to fasten planking together and to secure fittings, such as frames, to boats. Moreover, bark – another tree product – is used to build bark boats and some bundle rafts. The dominance of the tree in early boatbuilding was emphasised by G.F. Hourani, in his mid-twentieth century book on ‘Arab Seafaring’: he noted that a traditional Arab sewn-plank boat could be made solely from a coconut tree: planking, mast and other fittings from the bole, ropes, plank fastenings and sails from coir (the fibrous husk of the nut), and waterproofing oil from dried nut kernels.

In north-west Europe, ash, elm, hazel, alder, beech yew, lime, birch, willow and pine were sometimes used in boatbuilding but, wherever oak was available, it was clearly preferred for the main structural elements. Individual trees were carefully selected to match each job in hand: tall forest oaks with straight grain and without low branches had boles that were suitable for logboats, for long, straight, almost knot-free planks, and for keels and keelsons. Isolated oaks, on the other hand, produced naturally-curved timber that was needed for tholes, knees, frames, stems and other curved members (Fig. 1.5).

Fig. 1.5 A Norwegian thole fashioned from a crook to ensure strength.

Archaeological and historical evidence, and recent practice in Shetland and Norway, suggest that early boats were built of ‘green’ timber, unseasoned and therefore of relatively high moisture content. Such ‘green’ timber was easier to work, and the tendency for it to split and distort was minimised. The finished boat was then stabilised in a similarly high moisture content environment by transferring it to its natural habitat, the sea.

After the crown and major branches had been removed from a felled tree, the resultant log was stripped of its bark and sapwood. From such a log, or sometimes a half log, logboats were hollowed out. Whole, straight logs were also converted into keels for planked boats. In prehistoric times, whole or half-log oaks were converted into planks, thus achieving the maximum plank breadth from near the diameter of the log; in medieval times pine logs (of smaller diameter than oak) were similarly converted. Oak planks for medieval boats built in the Nordic (‘Viking’) tradition were split radially from oak logs (Fig. 1.6). Such ‘clove boards’ are stronger than planks converted in any other way; they shrink less in breadth, are less liable to split or warp, and are less easily penetrated by fungi. Splitting radially also minimises the number of planks with knots in them, and the wedgeshaped cross sections of each plank admirably fit the overlap, a distinctive feature of clinker planking.

Fig. 1.6 Diagram showing two ways of converting logs into planks:

Oak: An Oak log was converted into radial planks by first splitting the log in half; then halving each of those halves; and so on.

Pine: Pine logs (of smaller diameter) could best be converted into two planks, one from each half.

The lower diagram shows how a plank orientated radially in its parent oak log has rays running the breadth of the plank (a) and therefore will be strong; a plank orientated tangentially (b) would be less-strong.

Nowadays, an experienced forester would expect to produce twenty sound, radial planks per log; in medieval times, more may have been achieved. This method of log conversion persisted in north-west Europe until the fourteenth century when saws began to be used for shipbuilding and it became possible to convert logs in a variety of ways. Saws generally follow a straight line, regardless of the grain, whereas radially splitting an oak log, using beech or metal wedges, follows natural lines of cleavage (‘grain’) and the boards thus produced are stronger than sawn boards.

In Britain, the individual stitches used to fasten together the planks of the Earlier Bronze Age Ferriby boats were made from un-split yew withies, twisted and cracked to make them flexible. The continuous, sewn fastenings of the Brigg ‘raft’, of the Later Bronze Age, consisted of two, inter-twinned, split strands of poplar/willow. Two-stranded birch rope was used to repair a split in the Appleby logboat of c. 1100 BC. By late-medieval times rigging ropes were much as we know them today: at Wood Quay in Dublin, ten to fifteen yarns of split or whole yew withies were bundled into strands, and two strands were then laid up right-handed to make a rope of some four inches girth.

Boats can be built with a relatively simple tool kit: the Nootka Indians of America’s west coast used bird bones to bore holes, and the Chumash Indians of California used flints and whalebone wedges to build seagoing, sewn-plank boats. In early-twentieth century Oceania, boats were built with stone and bone tools. Elsewhere, shells were used for tasks that, today, we would use axe, adze or scraper. In early technologies everywhere, a simple kit of non-metal tools was used to build, what excavation shows to have been, splendid examples of the boatbuilder’s art.

In the absence of wind-uprooted trees or of driftwood, living trees must be prepared for felling by lopping-off branches using stone or (later) metal, axes. Maori woodsmen felled totara pine trees using stone tools and a ballista-powered, or swing, battering ram to cut into a tree’s base. There is also much ethnographic evidence for the controlled use of fire. The crown and any remaining limbs were removed, and wedges, levers, ropes and rollers used to manoeuvre the resulting log into a position where it could be converted. Bark and sapwood were then removed and surplus timber cut away to produce something near the final shape required.

When planks were to be fashioned in northern Europe, oak logs were split by wedge, mallet and lever, until pitsaws and sawmills become common in the later middle ages. A plank was fashioned from each half of a split pine log, thus obtaining maximum plank breadth. Certain timber species may be be...