![]()

Chapter 1

‘Peril from above’

The bombardment of cities from the air was a leitmotif of novelists in the years before the Great War, and the spectre of bombs falling on London was a regular theme. At this time, the world’s most powerful airships were all German. Each was as long as a battleship, could stay aloft for hours and could carry a dozen men and several tons of bombs. No other country had anything as impressive, nor did any aeroplane have remotely the same performance. Equally important, this was a time when Anglo-German antagonism was at its height. In his 1908 novel War in the Air, H.G. Wells vividly described German airships bombing faraway New York; and one of the most popular plays on the London stage in 1909 was Guy du Maurier’s An Englishman’s Home, which dramatized an invasion of Britain by a thinly-disguised Germany.1 Alarmist warnings began to appear in newspapers too, like this one from The Daily Mail:

OUR PERIL FROM ABOVE

Are so many of us indifferent still because we do not understand? Do we realize, from what we read in the daily press, that a foreign Power – and a Power regarded as a potential enemy – has perfected an aircraft which will fly, at the speed of an express train, for several days and nights without alighting? Do we realize that this machine – evolved at immense cost and after years of patient labour – is at last a practical warcraft, with a powerful, duplicate engine plant, a crew of specially trained navigators and an installation of wireless telegraphy which will flash a message several hundred miles? Do we realize that such aircraft, if launched against us with hostile intent, could steal across the North Sea at night, and rain down tons of incendiary and explosive bombs upon vital points of our coastline, and on London itself? Do we realize that, even after ceaseless warning, we lie practically defenceless against this peril, which grows from day to day?

In 1910, the Aerial League,2 one of several independent voices urging greater preparedness in military aviation, produced a pamphlet which saw the nerve centres of Britain as imperilled. By 1913, dozens of mysterious airships were being reported from all over the British Isles. The reality of these phantom airships, or ‘scareships’, can be ruled out in nearly all cases, but it was widely believed that they could only be Zeppelins. In part, this was because it was thought that only Germany was able to undertake airship flights to Britain, but it was also assumed that only Germany would want to carry out such missions.

That the British press obsessed so much about the danger posed by German aerial supremacy is probably due to the persistence of the effects of earlier scares and panics about German spies, German invasions and German dreadnoughts.3 The dreadnought crisis (‘We want eight and we won’t wait’ was a newspaper headline of the time) had taken place in 1909, and since then certain sections of the press had been obsessed with hunting German spies, who were apparently everywhere.4 In 1910, The Sketch ran a series of cartoons by William Heath Robinson about spies in England, including one showing them dangling from trees in Epping Forest.5 German periodicals boasted that the Zeppelin would give the British what was coming to them, so it seemed plausible that Germany was sending over its new weapons by night to spy on Britain, or even to practice navigation and bombing techniques for a future war. And Conservative newspapers did not hesitate to use the ‘fact’ of German aerial espionage as a cudgel with which to beat the Liberal Government for its slow progress in forming an air force.6 Despite this feeling, there was little belief in British Government or military circles that air attacks on civilians would soon become an integral part of modern warfare; for many the real threat posed by aerial warfare seemed less menacing than the literary one.

The outbreak of the First World War quickly altered these perceptions. In Germany, Major Wilhelm Siegert assembled the innocuous sounding Brieftauben Abteilung (Carrier Pigeon Unit) and mounted the first token raid on Britain’s Channel ports on 21 December 1914, when a Friedrichshafen FF29 sea-plane dropped two bombs in the sea near the Admiralty Pier at Dover. A further sea-plane raid on Dover followed on Christmas Eve, when a bomb was dropped in the garden of a house, enabling The Times to report that ‘the threatened German air raid has to some extent become an accomplished fact’. The ‘carrier pigeons’ were not to achieve a great deal with their raids, but these pin-pricks were to be followed by much more deadly attacks over the next four years. And some of these raids were to have devastating effects on the rapidly growing south-west corner of the county of Essex.

The late-nineteenth and early-twentieth century expansion of metropolitan Essex was perhaps the most remarkable feature of the county’s recent history. By the 1890s, Barking and Ilford were joined in continuous growth to East Ham; by 1900, West Ham, East Ham, Walthamstow and Leyton had all been linked to London’s growing suburbs. Between 1891 and 1911, Leyton’s population grew from 63,000 to 125,000 and Ilford’s from 11,000 to 78,000. By 1911, almost every acre of land in West Ham and East Ham had disappeared under development: three wards in West Ham – Tidal Basin, Canning Town and Plaistow – each had a population of more than 30,000, making them larger than most of the county’s municipal boroughs; and East Ham was England’s eleventh-largest town. By 1914, some 700,000 people, more than half the population of Essex, were concentrated in less than ten per cent of the county’s area. Yet despite this rapid growth, there was still agricultural land to be found in parts of that ten per cent, as rural as anywhere in the deepest Essex countryside.

This map was given away by The Daily Mail in 1919 and shows where some of the bombs fell in London and the surrounding area. The north-east quarter of the map, beyond the London County Boundary dotted line, shows part of the metropolitan Essex area. (Author’s collection)

![]()

Chapter 2

‘Our nerves are on edge’

Zeppelin design

A Zeppelin was a type of large rigid airship pioneered by the German Count Ferdinand von Zeppelin at the end of the nineteenth century. It was based on designs he had outlined in 1874 and detailed in 1893. His plans were reviewed by a committee in 1894, but little interest was shown so the Count was left on his own to bring his idea to fruition.

The first Zeppelin flight took place on 2 July 1900 over Lake Constance. It lasted only eighteen minutes before Luftschiff-Zeppelin LZ1 was forced to land on the lake. It was largely due to support by aviation enthusiasts that von Zeppelin’s idea got a further chance and would be developed into a reasonably reliable technology. Only then could the airships be profitably used for civilian aviation and sold to the military.

Before the First World War, a total of twenty-one Zeppelin airships (LZ5 to LZ25) had been manufactured. In 1909, LZ6 became the first Zeppelin to be used for commercial passenger transport. The world’s first airline, the newly founded Deutsche Luftschiffahrts AG (DELAG), offered scheduled flights and had bought seven Zeppelins by 1914, by which time German airships had flown over 100,000 miles and carried 37,000 civilian passengers.

The German military, realizing the airship’s potential for warfare, ordered several, the first entering service in March 1909, three years before the formation of the Royal Flying Corps (RFC) in Britain. At the outbreak of war, Zeppelins were used almost immediately, offensively bombing the Belgian cities of Liege and Antwerp on the nights of 6/7 August and 25/26 August 1914 respectively, killing several citizens in their homes.

The basic form of early Zeppelins was a long cylinder with tapered ends and complex multi-plane fins. During the Great War, following improvements by the rival firm Schütte-Lanz Luftschiffbau, the design was changed to a streamlined shape and cruciform fins used by almost all airships ever since. Within this outer envelope, up to nineteen separate balloons, also known as ‘cells’ or ‘gasbags’, contained lighter-than-air hydrogen gas. For most rigid airships the gasbags were made of many sheets of skin from the intestines of cows. About 200,000 were needed for a typical First World War Zeppelin. The sheets were joined together and folded into impermeable layers. Crews included a sail-maker to repair small tears and holes in the gasbags.

The most important feature of Zeppelin’s design was a rigid skeleton of aluminium or wood, made of rings, longitudinal girders and steel wires. This meant that the aircraft could be much larger than non-rigid airships (which relied on a slight over-pressure within the single gasbag to maintain their shape). This enabled Zeppelins to lift heavier loads and be fitted with increasingly powerful engines. Catwalks along the skeleton allowed crew members to move through the airship, and a vertical ladder gave access to the outside through the top of the hull.

Forward thrust was provided by internal combustion engines mounted in cowlings connected to the skeleton. A Zeppelin was steered by adjusting and selectively reversing engine thrust and by using rudder and elevator fins. A comparatively small compartment for crew was built into the bottom of the frame, but in large Zeppelins this was not the entire habitable space; they often carried crew internally too.

By 1914, state-of-the-art Zeppelins had lengths of 500 feet and volumes of nearly 900,000 cubic feet, enabling them to carry loads of around 9 tons. They were typically powered by three Maybach diesel engines of around 400–550hp each, reaching speeds of up to 50mph.

There were two types of ship operated by the air forces of both the German army and navy as two entirely separate divisions. The first was the Schütte-Lanz airship, which had a wooden frame. These machines were operated by the army. The other type was the aluminium-framed Zeppelin which found favour with the navy. At the beginning of the war the German army had nine machines (including three DELAG craft requisitioned from civilian ownership), the navy had four. All the craft were identified with the pre-war prefix LZ and a number; to avoid confusion between craft with the same number it is customary to use the prefix LZ for army craft and just L for navy craft (the Schütte-Lanz and Parseval types are sometimes identified with the respective prefixes SL and PL).

There were major differences in doctrine between the two services: the army emphasized bombing from a low level and close support of ground forces, while the navy had trained for reconnaissance and it was these fliers who carried out most of the airship bombing raids over Great Britain. Initially, the main use of Zeppelins was in reconnaissance over the North Sea and the Baltic, where the endurance of the airships led German warships to a number of Allied vessels. Zeppelin patrolling had priority over any other airship activity and during the war around 1,200 scouting flights were made. The German navy had some fifteen Zeppelins in commission in 1915 and was able to have two or more patrolling continuously at any one time, almost regardless of weather. They prevented British ships from approaching Germany, spotted when and where the British were laying mines and later aided in the destruction of those mines.

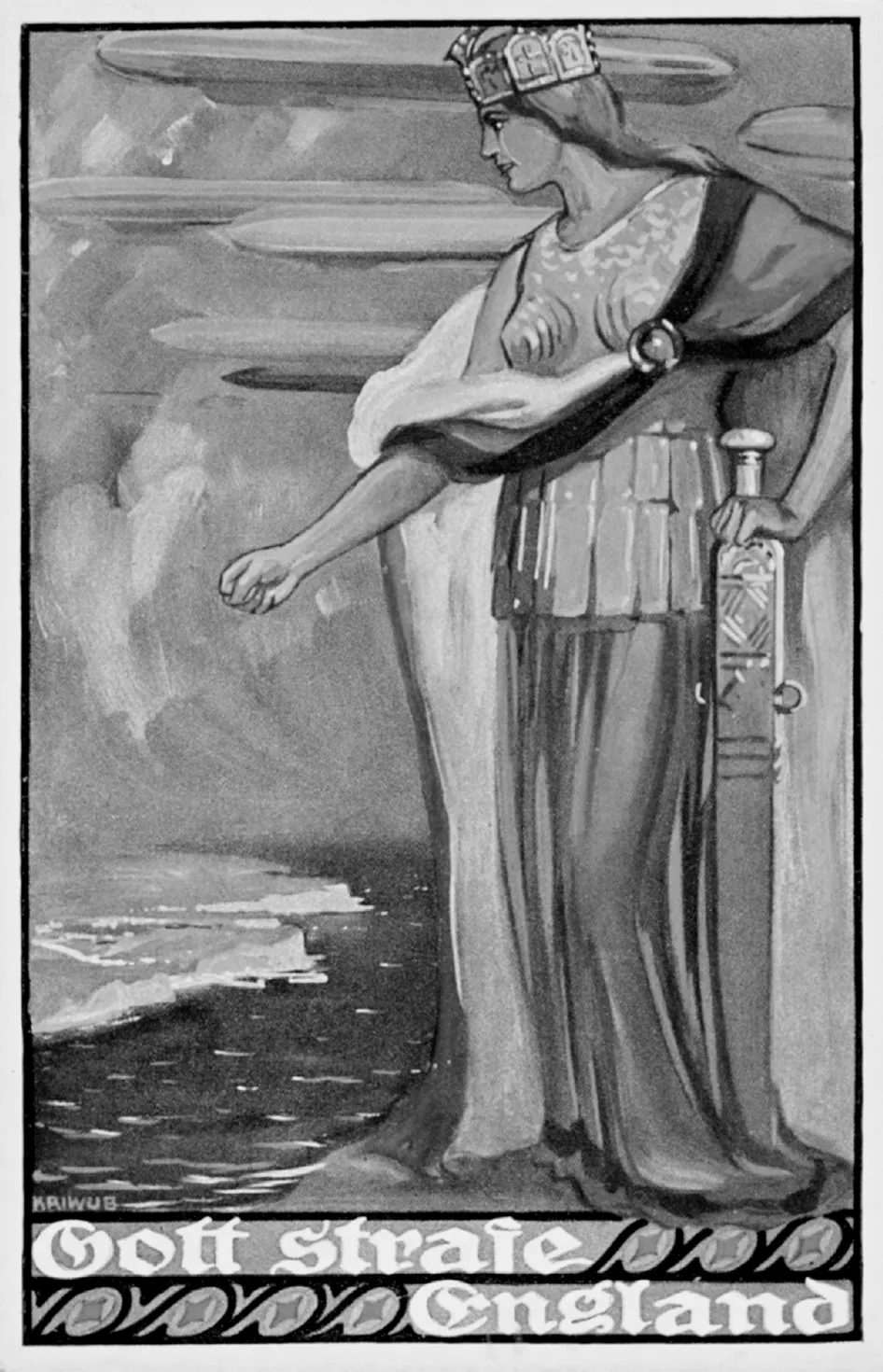

This was just one of a multitude of German propaganda postcards featuring Zeppelins. (Author’s collection)

Navigation

Flying a Zeppelin from Germany (or from occupied Belgium, where Germany also had airship bases) to London was not easy. The complicated systems of the Zeppelins were prone to breakdown, meaning many missions had to be aborted. Also, although Zeppelins could fly in almost any weather conditions, they were very much at its mercy. Cloud cover made navigation a nightmare, but moonless nights also had advantages since the defenders could not spot Zeppelins approaching in the darkness. Unexpected storms could damage airships or cause them to drift off course. Even when everything worked and the weather was clear, finding London was still a challenge.

The raiders lifted off from their seaside bases in the early afternoon, crossed the English coast at dusk, arrived over their targets around midnight, then attacked and headed for home before daybreak. They flew at an altitude out of range of AA guns and safe from the fragile and underpowered British fighters that rose to challenge them. Once over their target, the Zeppelin crews dropped parachute flares temporarily to blind the gunners below, or flew into a cloud or fog bank to hide from their pursuers.

Navigation was crude at best and, with no real navigational instruments, Zeppelin crews were forced to find their way by using maps and recognizing landmarks on the ground. They relied on railway tracks, the lights of towns, or the sheen of rivers, lakes and reservoirs to guide them to their targets. The only instruments in the command gondola other than ship controls were a liquid compass, an altimeter, a thermometer and an airspeed meter. To determine their location, the commanders had to use dead-reckoning, relying on what landmarks were visible from high altitude, and an inaccurate system of radio bearings, in which the airship would call for bearings and various stations in Germany would measure and compare the direction of the radio waves and estimate the vessel’s location. When raids on Britain started, the German navy’s High Command established radio stations at Nordholtz and Borkum to direct and help the Zeppelins. Not only did this crude system have a margin of error of several miles, but it also helped the British track the Zeppelins by listening to the German freq...