![]()

PART 1

IN THE KILLING FIELDS: CAMBODIA, 1980

![]()

Chapter 1

Crossing Borders

The forest in Cambodia was noisy with exotic birdsong but the makeshift hospital in a clearing was quiet as always. Peaceful wasn’t the right word: the atmosphere was subdued and wary. Already by noon I had seen more than fifty patients with malaria. Some were severely affected and I knew that two of them, despite treatment, would die before tomorrow morning. I hadn’t expected that within the next hour I would see five people killed by shell and gun fire.

It could hardly be called a hospital. The wards were just four huge bamboo shelters open at the sides and covered with palm leaves for a roof. It had been built in an isolated part of western Cambodia by refugees fleeing from the chaotic and brutal fighting to the east but it was only 200 metres from the border with Thailand.

The air was hot and humid and I was so used to the incessant rasping of crickets that I hardly heard them now. The constant rhythm was suddenly broken by a deep, booming sound which I thought was thunder, but this was the wrong time of year. Everything stopped in the hospital as people listened; even the birds fell silent. The sound came again, and again. Was it getting closer? Out of the forest from the direction of a refugee village, people were running. Men with armfuls of AK-47 assault rifles were handing them out. Women were carrying babies or small children. Other older children followed them crying. The Cambodian nurse, Chantrea, who was helping me with the patients, pulled me out of the bamboo ward ...

‘Come with me. It’s the Vietcong,’ she shouted. ‘They’re attacking the village. They’re shelling it. Get to the bridge, get into Thailand.’

‘What about the patients?’ I asked. Most of them were running with us but some, the very ill, were left behind.

‘Go. This is not safe for you,’ she said, as she pushed me towards the narrow bamboo bridge over a small ravine which marked the border with Thailand.

As I crossed the bridge with the three other members of the Red Cross team, I expected the Cambodians to follow, but a number of armed Khmer Rouge soldiers, the infamous communist fanatics who, it was said, had murdered over three million of their fellow Cambodians, stood like sentries preventing them from passing. There would be no deserters here. Everyone would have to turn and fight.

I heard shooting from the direction of the village, then distant machine-gun fire. We waited and after twenty minutes there was silence. It was an hour before the tension eased. We tentatively made our way back over the bridge and work was resumed.

Chantrea told me the attack had failed but there had been casualties. Many had been killed and they were bringing the wounded to the hospital. The first was a woman of maybe 25 who had been hit in the chest by shell fragments. It was hard to see the blood which had soaked her black shirt but a tear in the fabric showed where a large piece of metal shrapnel had entered her right lung from the front. I suspected it had hit her aorta or one of the other main blood vessels near her heart; her face was white, her voice was weak and I could hardly feel the rapid, feeble pulse in her neck. There was nothing much I could do. We could only give basic first aid here, but I doubt if even a specialized surgical unit could have saved her. As I crouched over her trying to find a vein to set up an intravenous drip, her breathing stopped, her pulse disappeared and her frightened eyes looking at me became lifeless as she died.

We dealt with ten wounded Cambodians that afternoon and five died. I asked if there had been any Vietcong casualties to deal with. Chantrea seemed surprised at the question but said that some of them had been wounded by the personnel mines that protected the forest trails leading to the village. I asked where they were.

She paused and looked straight at me. ‘There will be no prisoners.’

Six weeks before, I had been working in the UK as a junior doctor in anaesthetics and intensive care in Reading. It was September 1980, I was 32 and tired. Junior doctors’ hours were very long in those days – often 90 hours per week, sometimes more. The operating theatres were windowless, lit by harsh fluorescent light. In the coming winter months I would arrive in the dark and leave for home in the dark. It was all becoming stale. I felt I needed and deserved a short break.

I listlessly scanned the advertisements for appointments in the British Medical Journal but saw nothing at all that appealed to me until I glanced at an advertisement by the British Red Cross for general medical officers to go to Thailand for three months. I looked out of the window at the cold, rainy and gloomy dusk outside. I longed for some sun, warmth and fresh air – and a short working holiday in Thailand was very appealing.

When I casually phoned them to get more information, I admitted I probably didn’t have the experience they needed but maybe they would consider accepting me – if not now then in a few years’ time for a similar job. They asked how soon I could leave – they wanted people now. I had asked them at the right time. They explained the position: Cambodia was in chaos and vast numbers of Cambodians, or Khmer as they are called, were suffering. The Vietnamese army had invaded Cambodia and large numbers of refugees had fled from the warfare, mostly west to Thailand to escape. Now over 600,000 people, many ill and wounded, were crowded just inside Thailand in makeshift refugee camps.

The International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) in Geneva had mounted one of the biggest rescue projects in its history and was asking the national Red Cross societies, including Britain, to sponsor large numbers of medical staff to go out to their refugee camps on the Thai–Cambodian border. They reassured me that these medics were generally working in camps in the safety of Thailand.

I took just a few hours to think about it. Family and friends thought it wasn’t a bad idea – have a rest and come back refreshed and eager again. One of my consultants said I was making a mistake if I stepped off the NHS career ladder – I would find it hard to get another NHS post.

Three days later I was on my way to Southeast Asia. The long-haul flight to Bangkok, with the enforced rest and nothing to do, gave me a chance to almost stop the clock for a few hours and to take stock. I’d always wanted adventure. I was born into a modest family in a small town in Lancashire where they made buses. My father was a shoe repairer who hated his job and died when I was in my teens, probably from all the leather dust he inhaled. He once told me not to do as he had done: ‘If you’re ever unhappy with what you’re doing, then go out and do something else.’ I never forgot that.

It was otherwise a contented childhood in a close family and close community revolving around the parish church, secure, unchanging and parochial, with no need to go very far from it. I had no complaints, but there was something missing, some excitement. I was born on a Thursday ... my mother used to say, ‘Thursday’s child has far to go’ and I used to look at the horizon.

I got the A-level grades needed for medical school, and blessed with a full and free grant I was off to University College Hospital in London. It was the first adventure, but it wasn’t quite enough to satisfy my curiosity about the world. It just started the craving for more.

Yet as I sat on the Thai Airlines plane, I began to have some doubts: I was still only a junior doctor with little experience and I knew almost nothing of tropical medicine. But I reminded myself that this was only a one-off experience for three months. I could regard it as a holiday. I wasn’t motivated by altruism but by the need for a change of scenery and an innate curiosity. I never imagined it would be just the first of fourteen missions for the Red Cross.

Thailand was hotter than I’d expected and the ICRC headquarters in Bangkok more frenetic. I felt I was in the way. The personnel department only had time to hand me a folder of information before I was immediately sent east, still jetlagged, towards the Cambodian border. It was a five-hour journey in an ICRC minibus with half a dozen other recruits; I was the only one from the UK.

We left the world of Bangkok tourists behind and passed through flat, rich green countryside, small isolated farms and endless watery fields of rice. Two children on the veranda of a wooden house-on-stilts were happily splashing water from a huge water pot. They stopped when they saw the strange people in the bus and waved to us. We passed an ornate temple and a saffron-robed monk with his begging bowl.

It was very peaceful and pleasant and bright as I half-dozed in my seat with the sunlight and the heat and the fragrant smells coming in through the open window, a welcome change from the cold dullness of the UK and the sunless operating theatre I’d hurriedly left; but as the miles passed I thought to myself with some apprehension, ‘What on earth am I doing here? I’m getting nearer and nearer to a war zone!’

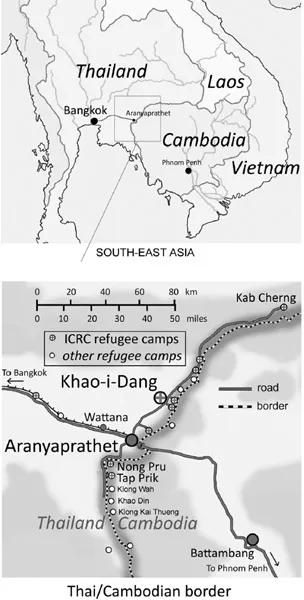

ICRC was based at the Thai town of Aranyaprathet, right on the Cambodian border. Here the main highway and the railway line from Bangkok once passed through the border on to the Cambodian town of Battambang and then the capital Phnom Penh. The border area was now very tense – the nervous Thai military were very prominent. The road and railway had been closed just before the border – a blockade with signs in several languages warned people away. In those days, Cambodia was a very dangerous place to visit.

ICRC headquarters had been set up just before Aranyaprathet in the hamlet of Wattana Nakorn. ICRC had rented a former large farm here with a wide area of concreted ground and hard clay and had erected thatched huts as accommodation. A huge open-sided warehouse was used as a dining area. It was quiet and almost deserted when I arrived in the late afternoon but within an hour the medical teams started to return from the camps. Wattana became a mass of noisy, hungry, dusty, tired or elated personnel, all heading for the makeshift showers and then dinner. There were 140 multinational expatriate medical personnel based here. It was a huge and busy operation. I mingled with them trying to find a friendly English accent among all the languages – French, German, Finnish, Dutch and more. I felt lost. Then I found an Australian Water and Sanitation team. ‘Sit down, mate, have a beer. We’re the dunny factory.’

I slept in my own prefabricated wooden hut under a mosquito net wondering exactly how far away I was from this war zone and listening to the loud noise of crickets and rain on the thatched roof. I was woken in the middle of the night by the sound of heavy vehicles, one after another, driving along the previously quiet highway. I was convinced they were tanks – the Vietnamese must be invading Thailand. Strangely, no one in the camp seemed to be stirring and I decided against rushing out and raising the alarm. I was later told that it was just Thai black market trucks heading into Cambodia which they did every night.

My internal clock was disturbed and I couldn’t go back to sleep. So I thought I’d read for a while. I found the folder of information leaflets hastily given to me in the ICRC office in Bangkok and decided I ought to find out more about the situation I was about to experience. There was no electricity in the hut so I lit a candle and read.

Cambodia or Kampuchea, the ancient empire of the Khmer nation, became independent from France in 1953 but only a few years of peace were left for this pleasant paradise with its gentle people. In the 1970s the Vietnam war spread into Cambodia and in the political chaos that followed, the communist party of Kampuchea ruthlessly took control. They were called the Khmer Rouge, led by Saloth Sar, otherwise known as the infamous Pol Pot. I never imagined at that moment that later I would actually see him in the flesh.

The Khmer Rouge immediately ordered the evacuation of all urban areas and the entire population was forced into the countryside to work on the land. Society would be brutally reshaped to conform to Pol Pot’s nightmarish social vision. They lacked food, tools and basic medical care. The communes were little different from concentration camps and the name Khmer Rouge itself struck fear into the people. The result was that hundreds of thousands of Cambodians died from starvation or disease and as many were executed in the ‘Killing Fields’. Most military and civilian leaders of the former regime were killed as well as anyone who opposed the Khmer Rouge or who simply did not or could not conform to their ideology. No one kept records of all those who died between 1975 and 1979 but it’s estimated that the Khmer Rouge executed 1.5 million of its own countrymen and a total of perhaps 3 million died out of a population of 7.3 million.

I put the leaflet down, disturbed by what I’d read. The plight of Cambodia at the time was not well known in the West and certainly not by me; the film The Killing Fields describing this horror was still four years away. I also realized that tomorrow I would become personally involved in this history lesson.

I was wide awake now as I continued reading. One nightmare was replaced by another in 1979 as the Vietnamese army, victorious against the US, successfully invaded Cambodia. Pol Pot’s struggling Khmer Rouge forces retreated west towards the Thai border. Along with them was a huge mass of Cambodian refugees who continued across the border for safety. The Thai authorities, eager that the conflict should not spread into their country, would let them go no further. More than half a million of them were now just a few miles from the hut where I was, at that moment, reading their tragic story. It was not the first or last time in history that frightened migrants would try to flee to safety.

The next day, the medical coordinator showed me a wall map of the Red Cross action. To the north, just off the border road, were the refugee camps with exotic names like Nong Sammet and Klong Singnang. The main ICRC hospital was situated inside Khao-i-Dang, the largest camp on the border, holding 160,000 refugees. In fact it was the largest in the world. The whole area was crowded with scores of other Voluntary Agencies, or VolAgs, of all nationalities extending right up to Laos. Some wit had termed this whole string of agencies the VolAg Archipelago.

The larger agencies like ICRC, Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) and Save the Children were kept busy, almost overwhelmed, but some of the much smaller groups with sometimes rather vague aims struggled to find any ‘customers’ they could help. They would almost pounce on the poor refugees as they crossed the border. One could imagine a Cambodian trying to reach the safety of Thailand – escaping the fighting, escaping the malaria, escaping the landmines – but finally getting caught by an aid agency.

The coordinator said, ‘I once came across a tiny aid organization up in the north that had cornered half a dozen miserable-looking refugees, too polite to escape, and the deal was that they would get a bowl of rice when they’d sung a few hymns. Most Cambodians are already devout Buddhists.’

He told us stories of individual medics from the West, not attached to any group, arriving at Bangkok airport with stethoscopes around their necks, taking a bus to the border and then trying vainly to find some organization that would take them on. The larger agencies wouldn’t touch them: there was no way in the field to check out who these people were and whether they had any qualifications at all.

He told me I’d start work tomorrow with a small medical team that had already been here for several weeks. The team served an area, not in the north but far away in an isolated area to the south of Aranyaprathet which was visited each day. Then he casually mentioned that our team was the only one which crossed into Cambodia itself. This didn’t sound good. I was expecting to work in the safety of Thailand. The team looked after two small hospitals just over the border; these were attached to two refugee camp villages, Nong Pru and Tap Prik. My team consisted of a Dutch doctor, Willy, who fortunately had some experience of tropical diseases, and three nurses, from Canada, USA and France.

![]()

Chapter 2

First Day

So on my first working day the five of us gathered at the main ICRC delegation near Aranyaprathet. I’ll admit the apprehension was growing – we would be crossing the border into a war zone. There was a more disturbing surprise to come. I asked Willy why these refugees were still in Cambodia, not in the safety of Thailand.

‘Because the Thai government won’t let them in,’ said Willy.

‘Why not?’

‘Because they, and the whole area we work in, are under the complete control of the Khmer Rouge.’ He added, ‘The Khmer Rouge want to stay in Cambodia because they’re still fighting the Vietnamese from there.’

This mission was already becoming something of a nightmare. Today and every morning the team would have a briefing with the Swiss security delegate for the southern area whose job it was to assimilate all the reports of military activity, assess the situation and decide wheth...