- 272 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Evolution of Airborne Operations, 1939–1945

About this book

The development of air transport in the early 20th Century led military strategists to examine the concept of inserting light infantry at key points behind enemy lines by air landing and air drop.The Germans were first off-the-mark with assaults in Norway and at Eben Emael in 1940. Crete saw a larger scale attack but while ultimately victorious the cost of men and equipment involved deterred any further Axis operation.The Allies on the other hand developed the concept dramatically with the large scale operation HUSKY in Sicily. While only partially successful there was massive loss of life and aircraft airborne operations were a key, if relatively minor, element of Op OVERLORD The D-Day Invasion.The most famous airborne operation was the large scale but ill-fated MARKET GARDEN. Almost successful the Arnhem battle goes down as a heroic defeat. The culmination of WWII airborne operations was the multi-division Rhine Crossing VARSITY.Expert author and collector Roy Stanley traces the history of airborne landings in words and pictures.

Trusted by 375,005 students

Access to over 1 million titles for a fair monthly price.

Study more efficiently using our study tools.

Information

Chapter I

INTRODUCTION

No matter what the size or objective, an airborne assault is a daring offensive operation.1 There were many small ‘Special Ops’ uses, such as extracting Mussolini from captivity in Campo Imperatore. The Japanese used paratroops three times and lost most in each try because of insufficient numbers committed (they also had gliders but never used them operationally). Italians dropped small contingents to destroy Allied aircraft in North Africa and the Soviets had at least two large drops. Most of those were side-shows involving small forces and not directly part of major campaigns. This book looks at the big drops/landings inserting infantry behind enemy lines in large numbers in an attempt change the initiative of a battle or campaign.

As usual in peacetime, the decades between the two World Wars saw senior officers concentrating on obtaining funding and their next promotion. Junior officers spent time training and thinking about how to do the job better. The more time they had, and fewer resources given them, the more thinking they did and the more radical the resulting ideas.

The Great Depression dried up resources, challenging military professionals to do more with less. When you have fewer troops, fewer guns, tanks and planes, husbanding them looms larger. You still have a job to do so you get creative.

Through the 1920s and 30s, military professionals all over the world reflected on the horrors of First World War trench warfare, minutely reexamining every battle, searching for a ‘truth’ that would avoid stalemate. Trench warfare was combat that ate men, destroying whole generations in England, France, Germany, Italy, and Russia with no appreciable gain for the price. Expecting war would come again, like any career professionals, military men considered their future. Haunted by the human wastage in 1914–18, they looked for new ways to resolve armed conflict. Soldiers had gone to ground in the face of ever more efficient rifles, machine guns and artillery. Trench lines, steadily more elaborate through the twentieth century, resulted in defenses that couldn’t be outflanked and could only be broken by frontal assaults with losses so high they were no longer acceptable. Combat in Spain, China and Manchuria in the late 1930s quickly devolved into trench warfare. It looked like nothing had changed tactically. There had to be a better way.

The profession of arms is devoted to protecting a nation or winning any engagement where the nation decides armed force is required. Squandering your army on futile head-on attacks against defense positions housing machine guns and artillery doesn’t serve either end, so an enormous amount of ‘gray matter’ was churning with imaginative planners advocating new (sometimes harebrained or impossible) ideas. Typically, ‘Old Guard’ upper ranks were wary, if not contemptuous, of ‘newfangled’ ways to fight.2 The only consensus was that a modern military should be manned, equipped and use tactics designed to end battle quickly and decisively—no lengthy stalemates next time.

This was a period of intense intellectual activity by retired and active duty officers seeking a magic bullet to negate the stagnation of trench warfare resulting in many ideas for tactics and equipment to avoid the horrific attrition of deadlocked trench warfare. Some of the ideas were sound and eventually came into use; others simply misspent scarce time and resources. Some advocates became zealots, writing convincingly in professional journals with passion and conviction that their vision was the right one. A few prophets gained followings. Armored vehicle pioneers Basil Liddell Hart, J.F.C. Fuller, Rommel and Charles de Gaulle pushed for larger, faster, better gunned tanks assuming the traditional role of cavalry or as a battering ram to open the door for regular infantry. In 1932 British PM Stanley Baldwin told Parliament, ‘the bomber will always get through.’ Airpower advocates like Italian General Giulio Douhet and US Army General Billy Mitchell pushed for what evolved into strategic bombing. Fighter pilots like Claire Chennault said ‘no, the bomber would not get through.’ The men who made big guns said they could make them bigger. In America and England, aging admirals argued the merits and relative value of big-gun warships while USN and RN ‘Young Turks’ held that aircraft carriers would own the seas. Expanding use of unrestricted submarine warfare was another popular concept in Germany. No one had the answers so everything was in play. Most of the new ideas were to improve the offense and most were steadily reined in by the Great Depression. Many of those ideas debated in Officer’s Clubs and professional journals involved somehow exploiting the exciting and rapidly evolving technology of aviation.

European states that suffered the recent war on their soil, those with larger, bellicose neighbors, thought defensively. Philosophically led by men like Andre Maginot, France, Belgium and The Netherlands turned to modern designs of fortified defense lines facing Germany, barriers strong enough to deter or stop an aggressor at their borders (France also fortified its border with Italy). Thicker concrete and more steel was their hope. Even offensive-minded Germany followed suit with its Siegfried Line just east of the Rhine eventually reaching from Switzerland to the Netherlands.

You didn’t have to halt an aggressor at the border, just delay them. Passive defenses were cheaper in men and material than actual armed bastions, and there was great pressure to remain within budgets a nation could afford. One of the most used passive defenses was belts of ‘Dragon’s Teeth’. They were ‘state of the art’ when a US military attaché forwarded this 1939 photo of German defenses. Concrete obstacles were relatively cheap to build and didn’t require skilled labor. Their purpose was to block tanks and infantry; stalling them in fields-of-fire from strong-points and long-range heavy artillery as defense reinforcements moved forward.

Even more effective were elaborate belts of interlinked ‘Elephant’s Teeth,’ another popular antitank defense (this installation is German from 1939). German photos are used here because US Army attachés in Berlin weren’t collecting against an ally like France or Belgium, but a former enemy building up again was fair game.

Both sides used passive defenses extensively in lines that stretched for dozens of miles (as in this captured German photo of a slightly different French version).

Proliferation of border fortresses and defense lines reinforced the ‘offensivists’ with proof that their search for new ways to advance was needed.

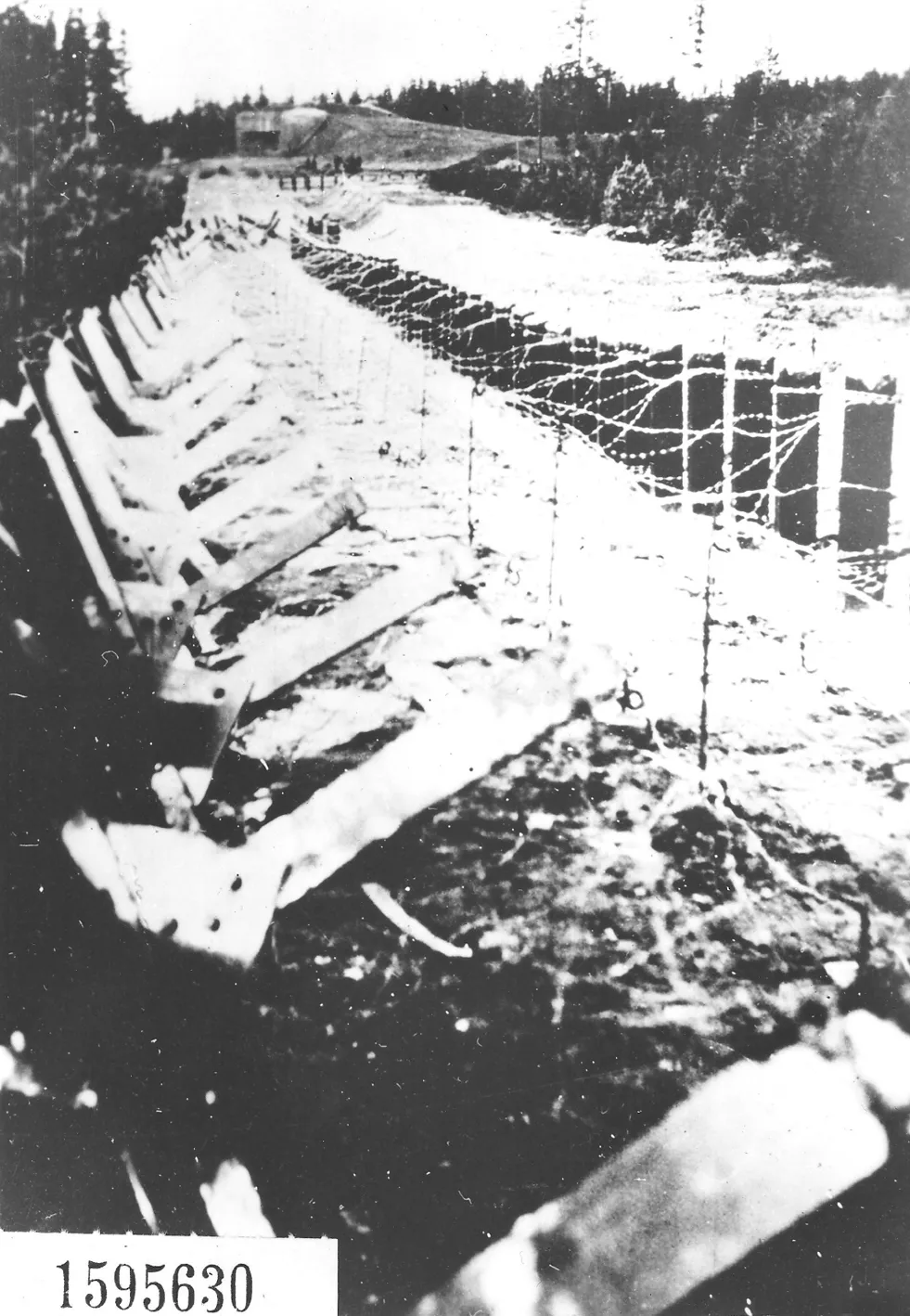

Military attachés of every nation forwarded to their Intelligence Services everything they could collect on defense lines as borders were being stiffened with wire and concrete. A few photos I screened came from covert collections but most were clipped from local magazines and newspapers (pre-Second World War security precautions and Intelligence collection were pretty naïve). The wire-lines below are very First World War in design. Steel tetrahedrons below were designed to stop tanks from breaking through. Similar ‘Czech Hedgehogs’ studded Normandy beaches in 1944. These passive defenses served to stall troops, making a killing zone for the armed strong-point in the distance.

Soldiers constantly improved barbed wire entanglements and tank barriers that delineated borders but the real defensive power came from manned nodes (well-armed forts) backed by mobile heavy artillery farther to the rear. Fire-power was counted upon to deter an enemy from attacking or decimate him if he moved across the line.

Some of the forts were quite large. Others were merely outposts, not intended to stop an enemy, rather to act as a trip-wire. If that classic medieval approach failed, larger forts would at least stall an attacker. No offense could press deeper leaving such a threat in their rear. Forts were intended to hold an attacker in place so his force could be subjected to heavy, long range artillery fire, giving time for defending reserves to be mobilized and moved to oppose the threat. That deterrent was expected to make an attacker think twice—or keep him at bay while seriously damaging his offensive capability well short of a nation’s heartland while defending troops remained safe behind steel and concrete.

This page from a German target study shows one gun of a French rail-gun battery supporting Maginot Line defenses from a location between Bitsch and Mutterhausen, threatening the area south of Pirmasens, Germany. The Germans used regular aerial photoreconnaissance beyond their borders to keep track of the locations of such guns.

A large caliber, long range rail gun is at (b), a munitions car at (d), (c) is a car to move projectiles and propellants to the gun and a light ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Dedication

- Foreword

- Chapter I: Introduction

- Chapter II: First Use – 1940

- Chapter III: An Op Too Many

- Chapter IV: Mediterranean

- Chapter V: Pacific Initiatives

- Chapter VI: Division-Sized Assault

- Chapter VII: Airborne-Centric Assault

- Chapter VIII: Far East Again

- Chapter IX: The Final Ops

- Chapter X: Afterthoughts

- Maps

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Evolution of Airborne Operations, 1939–1945 by Roy M. Stanley in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Military & Maritime History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.