- 320 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

An extensively illustrated reference covering four tumultuous decades that gave birth to the modern Royal Navy.

Winner of the Samuel Pepys Prize and Latham Medal

This reference book describes every aspect of the English navy in the second half of the seventeenth century, from the time when the Fleet Royal was taken into Parliamentary control after the defeat of Charles I, until the accession of William and Mary in 1689 when the long period of war with the Dutch came to an end. This is a crucial era that witnessed the creation of a permanent naval service, in essence the birth of today's Royal Navy.

Samuel Pepys, whose thirty years of service did so much to replace the ad hoc processes of the past with systems for construction and administration, is one of the most significant players, and the navy that was, by 1690, ready for a century of global struggle with the French owed much to his tireless work. This major reference for historians, naval enthusiasts, and, anyone with an interest in this colorful era of the seventeenth century covers:

"Davies writes clearly, knows his subject extremely well, organizes the material effectively, and covers each topic thoroughly . . . there's some new piece of revelatory detail on pretty much every page. If you're at all interested in seventeenth century sailing ships—especially English ships—this is a truly fascinating and rewarding book." — Corsairs and Captives

Winner of the Samuel Pepys Prize and Latham Medal

This reference book describes every aspect of the English navy in the second half of the seventeenth century, from the time when the Fleet Royal was taken into Parliamentary control after the defeat of Charles I, until the accession of William and Mary in 1689 when the long period of war with the Dutch came to an end. This is a crucial era that witnessed the creation of a permanent naval service, in essence the birth of today's Royal Navy.

Samuel Pepys, whose thirty years of service did so much to replace the ad hoc processes of the past with systems for construction and administration, is one of the most significant players, and the navy that was, by 1690, ready for a century of global struggle with the French owed much to his tireless work. This major reference for historians, naval enthusiasts, and, anyone with an interest in this colorful era of the seventeenth century covers:

- naval administration

- ship types and shipbuilding

- naval recruitment and crews

- seamanship and gunnery

- shipboard life

- dockyards and bases

- the foreign navies of the period

- the three major wars fought against the Dutch in the Channel and the North Sea

"Davies writes clearly, knows his subject extremely well, organizes the material effectively, and covers each topic thoroughly . . . there's some new piece of revelatory detail on pretty much every page. If you're at all interested in seventeenth century sailing ships—especially English ships—this is a truly fascinating and rewarding book." — Corsairs and Captives

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Pepys's Navy by J. D. Davies in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Military & Maritime History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part One

THE NAVY IN PEACE, WAR, AND REVOLUTIONS

CHAPTER 1

The End of the First ‘Royal Navy’, c. 1588–1649

ON 30 JANUARY 1649 KING CHARLES I was executed outside the Banqueting House of Whitehall Palace. For the first time in many centuries, England was without a monarch, and within months, a fully republican form of government, the Common-wealth, was in place. Exactly forty years later, on 30 January 1689, the guns of British warships fired a twenty-gun salute and dipped their flags to mark the anniversary of the ‘royal martyrdom’.1 The salute must have had a surreal quality of déjà vu, especially for the oldest witnesses to it, for on that day, and yet again, the three kingdoms in the British Isles had no king: Charles I’s younger son, James II of England and VII of Scotland, had fled his kingdoms in the previous December, and it would be another fortnight before the vacant throne was officially filled. On 30 January 1689, too, the navy was preparing for war. The formal declaration against France did not come until May, but hostilities commenced unofficially much earlier. From that time until the surrender of Napoleon Bonaparte on the deck of hms Bellerophon, 126 years later, war against France came to be perceived by many in the navy, at least, as the natural or desirable order of things; and for much of the time, it usually was. It was the navy of Anson, Rodney, Howe and ultimately Horatio Nelson, culminating in the period from about 1756 to 1815 that has been immortalised by historians, novelists and film-makers alike as the‘classic age’ of British naval history.

Samuel Pepys as secretary to the Admiralty.

(MEZZOTINT BY R WHITE AFTER THE PORTRAIT BY SIR G KNELLER)

(MEZZOTINT BY R WHITE AFTER THE PORTRAIT BY SIR G KNELLER)

This perception has led, consciously or unconsciously, to comparative neglect of the preceding period; what might be called the navy’s ‘long seventeenth century’, from about 1600 to about 1750.2 The naval campaigns of that time tend to be less well known than those that went before or came after, and the key figures in the development of the Royal Navy tend to be less familiar to general readers – with one notable exception, who actually serves to prove, rather than disprove, the point. Samuel Pepys (1633–1703) is one of the best-loved figures in cultural history, thanks largely to his remarkably frank and moving shorthand diary of the period 1660–9. A mine of information and gossip on music, literature, the theatre, court scandal, the Plague, the Great Fire of London and his own tangled love life, Pepys tends to be known first and foremost as a brilliant social commentator and a flawed but deeply attractive human being. But professionally, Samuel Pepys was a naval administrator, nothing else. Methodical, inquisitive and highly competent, he was also a formidably opinionated self-publicist who made enemies just as easily as he made friends. For almost thirty years, ten of them (1673–9, 1684–9) in the pivotal role of secretary to the Admiralty, Pepys was at the heart of one of the most important periods of transition in British naval history.3 In terms of the evolution of fighting tactics, professional development, administrative structures and procedures, and – much less tangibly – the navy’s perception of itself, the period 1649–89 was debatably the critical stage in its transformation into the fighting force that went on to build up an unprecedented record of victory during its ‘classic age’.

FROM ARMADA TO CIVIL WAR

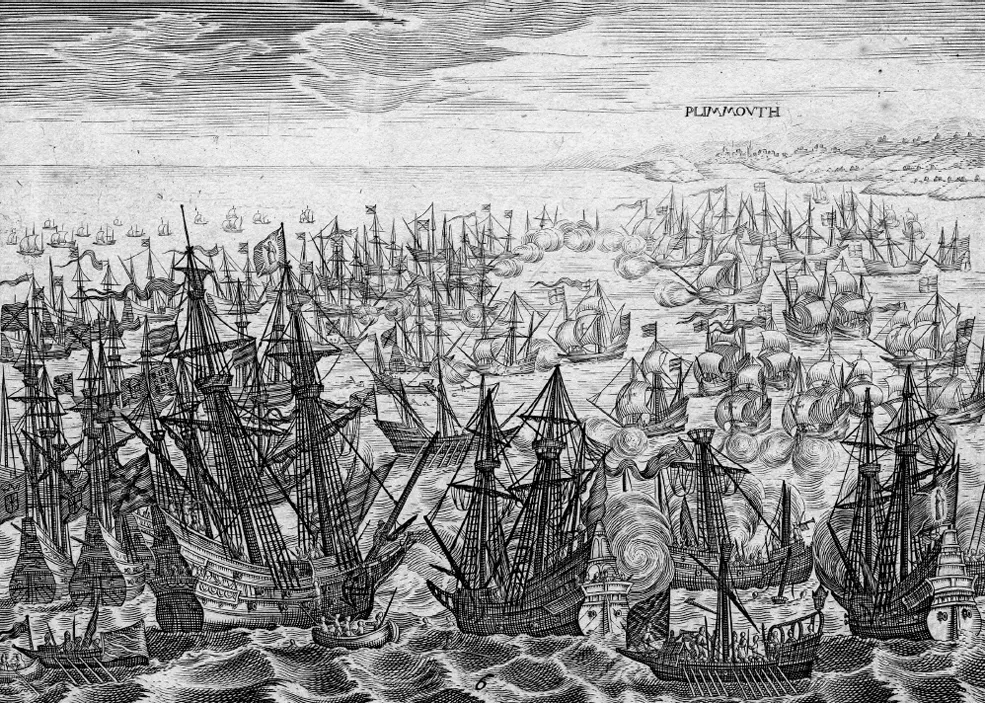

The victory over the Spanish Armada (1588) was gained by a navy that was still ‘medieval’ in many essentials. Only thirty-four of the 197 English ships were owned by the crown; the rest were supplied as private ventures by wealthy individuals or seaports. Although the best galleons were large, new and technically advanced, many of the other ships that put to sea on behalf of Elizabeth I were small, and of little use in battle against Spain’s floating arsenals. English tactics had moved away from the continental reliance on boarding, instead placing the emphasis on gunnery from longer range, but many soldiers still served on the fleet. The admiral, Lord Howard of Effingham, was an aristocrat appointed to the command by virtue of his social and political status alone, although the same was also true of his Spanish counterpart, the Duke of Medina Sidonia.4 The victory over the great Spanish invasion fleet was largely fortuitous, owing more to the weather than any tactical acumen or innate superiority on the part of Howard, his men and his ships, but it helped to create the myth of the English navy as the foremost bulwark of national defence. The Armada was only one campaign in twenty years of naval warfare from 1585 onwards, a collective experience that shaped the consciousness of Englishmen (Samuel Pepys included) for generations to come.5 Moreover, the longevity of several prominent naval men from the ‘Armada era’ ensured that the potent mystique surrounding the service of that time was handed down to succeeding generations. The last surviving captain who had commanded a ship against the Spanish Armada, Edmund Sheffield, Earl of Mulgrave, died as late as 1646, while a number of men who had commanded at sea under Drake or his contemporaries, the likes of Sir Henry Mainwaring and Sir Robert Mansell, lived on until the 1650s. The last Spanish prize from the Armada year, the Eagle Hulk, was ‘laid ashore for age at the north end of Chatham dock, 1675, and sold December 1683.6 Two heavily rebuilt veterans of the Armada fight, the Vanguard and Rainbow, survived into the Restoration era, the latter lasting until 1680; although the evidence is extremely dubious, the Lion, which survived until 1698, may have been first built in 1557, when England was still Catholic and still possessed Calais. Other Elizabethan warship names were regularly revived to inspire succeeding generations: Victory (1620), Triumph (1623), Tiger (1647), Dreadnought and Revenge (1660), Warspite (1666), Vanguard again (1678).7

The defeat of the Spanish Armada.

(© THE TRUSTEES OF THE BRITISH MUSEUM)

(© THE TRUSTEES OF THE BRITISH MUSEUM)

These abiding memories of the supposed ‘golden age’ of the Armada fight created a burden of popular expectation on those who served between 1649 and 1689. For instance, the supposedly ‘Elizabethan’ idea of a self-financing naval war, in which fleets seized control of their enemies’ economic lifelines – in other words, the state-sponsored piracy in which the likes of Drake had indulged – underpinned, at least in part, Oliver Cromwell’s desire to capture the Spanish bullion fleet in the 1650s, and Charles II’s wish to strangle Dutch trade in the 1660s and 1670s.* In reality, though, the ‘golden age’ was far less golden than nostalgia made it out to be, and the idea of the self-financing naval war was always a chimera. Successive campaigns in European waters and the Caribbean from 1589 to 1604 brought relatively little success; some, like the Earl of Essex’s attack on Cadiz in 1596 and Sir Francis Drake’s final voyage in the same year, were ignominious reverses. Only further gusts of‘Protestant wind’ dispersed two more Spanish Armadas, but even such favourable elements could not prevent a damaging Spanish landing in Ireland in 1601.8 The material condition of the navy also suffered, with crews going unpaid for long periods. Queen Elizabeth I, who had presided over it all, finally died in 1603, and England’s new monarch, King James VI of Scotland, wanted to establish a reputation as rexpacificus, a European peacemaker. He also had little real understanding of, or interest in, the navy that he had inherited; his cousin the Earl of Bothwell, hereditary Lord High Admiral of Scotland, was disparaging about James’s feeble credentials as an admiral.9

James quickly ended the nineteen-year-long war with Spain. Thereafter, and for the duration of his reign, the navy became even more neglected. Some new warships were built, such as the large Prince Royal of 1610, and a few expeditions were undertaken, such as the despatch in 1620 of a fleet under Sir Robert Mansell against the corsairs of Algiers, but on the whole, James’s navy and its Lord High Admiral, the Earl of Nottingham (the former Lord Howard of Effingham), were widely suspected of rampant corruption and inefficiency.10 Two major commissions of enquiry, in 1608 and 1618, and a new Lord High Admiral from 1619 onwards – James’s favourite, the future Duke of Buckingham – brought in some reforms, but the overall condition of the fleet remained poor. During his Algiers expedition, Mansell constantly bemoaned the weak and foul condition of his ships, the stinking beer, the ‘piecemeal and torn’ victuals and the constant back-biting and penny-pinching that he knew would be rampant at home.11 These problems re-emerged in the years 1625–9, when Buckingham and the new king, Charles I, embarked on the only large-scale naval wars that England would fight in the halfcentury between 1604 and 1652. Expeditions to the Caribbean, against Cadiz and to relieve the French Protestants at La Rochelle were poorly organised and ineptly commanded, and uniformly failed to achieve their objectives, comprehensively blasting England’s inherited reputation for naval competence and turning the country into the object of bad foreign jokes.12 In 1629 Charles abandoned both the wars and the institution of Parliament, which had proved increasingly fractious. Inevitably, funding of the navy suffered at first, but in the mid-1630s Charles and his Lord Treasurer, the Earl of Portland, extended the old medieval system of Ship Money (by which coastal towns paid for maritime defence) to the whole of the country. Despite some opposition, collection rates were far more impressive than they had been for parliamentary taxation, raising some £800,000 between 1634 and 1638, and Charles could finally embark on a sustained programme of naval reconstruction.

The Lion, allegedly a rebuilding of a ship first built in 1557; she was finally sold out of the service in 1698.

(RICHARD ENDSOR, BASED ON VARIOUS DRAWINGS AND PAINTINGS BY THEVANDEVELDES)

(RICHARD ENDSOR, BASED ON VARIOUS DRAWINGS AND PAINTINGS BY THEVANDEVELDES)

The centrepiece of the ‘Ship Money fleets’ was the vast Sovereign of the Seas of 100 guns, built at Woolwich in 1637 by Phineas Pett. She would be the centrepiece of many subsequent fleets, too, despite her cumbersome sailing qualities; she fought in all three Anglo-Dutch wars and, much later, against the French. All too clearly, though, the Sovereign was wholly inappropriate for the purpose that allegedly underpinned the levying of Ship Money, namely defence against the small, agile raiding craft used by Dunkirkers and the North African corsairs. In fact, her name is the best clue for the purpose that Charles really had in mind for her. It reflected the king’s legal claim to sovereignty over all of the ‘British seas’, which supposedly extended along most of Europe’s western seaboard. The claim originated in a distinctly dubious reading of the naval history of the Anglo-Saxon period, especially the reigns of Kings Alfred and Edgar and, thanks to the Stuart accession in England, of the migration into English law of the Scots concept of‘territorial waters’.13 The claim was given expression in print by John Selden in his Mare Clausum of 1635, written while the Sovereign was under construction. It manifested itself at sea in the ‘sa...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Preface

- Key Dates

- Part One: The Navy in Peace, War and Revolutions

- Part Two: Types of Ship

- Part Three: Shipbuilding

- Part Four: Officers

- Part Five: The Methods of, and Obstacles to, Naval Recruitment

- Part Six: Naval Crews

- Part Seven: The Work of the Ship

- Part Eight: Shipboard Life

- Part Nine: Dockyards, Bases and Victualling

- Part Ten: Foreign Navies

- Part Eleven: Strategy and Deployment

- Part Twelve: Tactics and Battle

- Part Thirteen: Aftermath

- List of Abbreviations

- Notes

- Appendix

- Further Reading