- 240 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Pocket Guide to Victorian Artists & Their Models

About this book

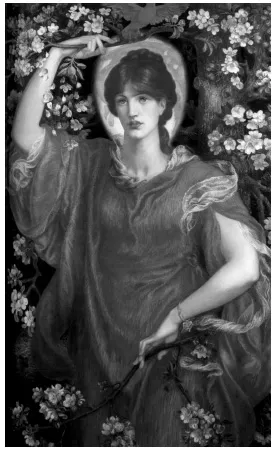

The Victorian era produced many famous artists and styles. John Everett Millais and Dante Gabriel Rossetti were part of the famous pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood whose willowy models were often seen in the works of several of the artists. One of the most famous was Elizabeth Siddall, an artist in her own right, who posed for Millais Ophelia, married to Rossetti, and posed for him, Holman Hunt and Walter Deverell. This fascinating book is a must for everyone interested in art and the Victorian era, and in the genres, styles and relationships between art and the events of the day. There are biographies of the artists and models, glimpses of their most famous pieces new insights into the vibrant Victorian art-world - the lives and loves, and the artists dealings with their patrons.Did you know?Rossetti tucked a book of his own poetry into Siddalls hair in her coffin and, later, arranged for her exhumation to reclaim it. After several years, the coffin had preserved her ethereal red hair.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Chapter One

THE PRE-RAPHAELITES

Back to the Future

Stephen Spender, in his article ‘The Pre-Raphaelite Painters’ (1945), called Pre-Raphaelitism ‘the greatest artistic movement in England during the 19th century’. Few can disagree that, in Britain at least, it was the most influential. How did it begin, and what did it achieve?

In the late 1840s, at London’s Royal Academy Schools, the brightest star – he’d entered as a child prodigy – was John Everett Millais, the youngest ever student and one from whom much was anticipated. Millais had befriended a fellow student, Holman Hunt, as had another student, Gabriel Rossetti. Less conscientious and already a rebel to the Academy, Rossetti had quit to become an awkward pupil to the slightly older (and equally rebellious) Ford Madox Brown. Hunt and Millais were already bosom friends when, in August 1848, Rossetti met with them in Millais’s comfortable Gower Street house (where he lived with his parents) and, while looking at a book of engraved early Italian frescoes, the three young men talked up the idea of an art student rebellion, in which they would reject the stuffy dictates of the Academy but, rather than carve a new niche as students like to do, they would rediscover the sharp and sincere simplicity of medieval painting before what they saw as its corruption through the stultifying polish of Raphael. They would emulate early masters; they would throw out contemporary rules and conventions and, instead of producing ‘studio’ pictures applauded by the Academy, would work directly from nature to reveal truth.

Rossetti, ever impulsive, invited what can only be called a motley band to join them: a budding sculptor, Thomas Woolner; an art student, James Collinson; one of Hunt’s students, F G Stephens; and Rossetti’s brother William – who had never made any great claim to be an artist. The group drafted a Pre-Raphaelite manifesto (which in retrospect seems remarkably tame):

1. To have genuine ideas to express

2. To study Nature attentively, so as to know how to express them

3. To sympathise with what is direct and serious and heartfelt in previous art, to the exclusion of what is conventional and self-parading and learned by rote

4. And most indispensable of all, to produce thoroughly good pictures and statues.

Laus Veneris by Burne-Jones (1873–8)

They would declare their intentions at the following year’s RA Exhibition, they decided, with works to astound the world. So far, so very student rebellion. Not for them still-lifes or unpopulated landscapes. For the 1849 Exhibition Millais prepared Isabella, a scene from Keats, Rossetti The Girlhood of Mary Virgin and Hunt a scene from a Bulwer-Lytton novel (Rienzi, in which Rossetti and Millais were his models). Each painting would bear the initials PRB (Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood). Rossetti, true to form, pulled out, and displayed his picture instead at the Free Exhibition in a minor gallery in Hyde Park. But the world was not astounded. Though the pictures were decently received, they created no sensation. No one noticed the meaningful initials.

The following year the still-unknown Brotherhood launched a putative student magazine, The Germ, which limped through four editions before closing with unpaid bills. Rossetti (a lifetime avoider of exhibitions) chose the Free again, while the others chose the Royal Academy. Rossetti, true to form again, spiced things up a second time by letting slip what the letters PRB stood for. And it was that which brought sensation.

It’s hard for us today to see why those three letters should cause offence. Why did the students call themselves a Brotherhood, people asked? Did they presume to challenge Raphael, the greatest painter of all time? What lay behind those gaudy paintings with Romanish imagery; were they Catholic propaganda, mounting a challenge to the Church? (The British Church was at the time fiercely split on issues of dogma: High Church, Low Church, the 39 Articles, Tractarianism, Newman, Pusey and the Catholic threat were all contentious issues.) The Press rose up, and the young men’s paintings were duly vilified. Today’s critics are milksops compared to the usually anonymous critics of that time.

Collinson’s entry, The Renunciation of Queen Elizabeth of Hungary, was harmless, but Hunt submitted a flagrantly Pre-Raphaelite painting, A Converted British Family Sheltering a Christian Priest from the Persecution of the Druids. (They liked long titles.) Millais entered three paintings: a portrait, a Shakespearian if Pre-Raphaelite Ferdinand and Ariel, and the one that would create the biggest brouhaha, Christ in the House of His Parents. This ‘sacrilegious’ and ‘offensive’ painting whipped up a critical storm. To be fair to the critics, it was unlike any ‘Bible picture’ seen before, but their criticism extended to each of the Pre-Raphaelite artists, in part because they were new, in part because they’d dared establish a ‘secret sect’.

The Brotherhood was shaken. Rossetti, under fire for having caused or provoked the storm, vowed to shun further public exhibition. Collinson resigned from the PRB. Woolner lay low. Millais was badly shaken, and had to be persuaded to stay in the group. But the volatile Hunt took umbrage and railed against the old men of the Academy – a loathing he never lost: even at the height of his fame he never joined. He now became leader of the Pre-Raphaelites. Never one to flinch from a fight, he encouraged Millais to fight on – and Millais, the one Brother from a well-off family, stood by his impoverished friend, finding him money and small commissions. Among the Brotherhood, Millais was the only one with any kind of reputation, a reputation based on his pre-Pre-Raphaelite years.

At the next year’s RA Exhibition (1851) Millais showed another three paintings: The Return of the Dove, The Woodman’s Daughter and Mariana. Hunt chose a different literary scene, Valentine Rescuing Sylvia (from Shakespeare’s Two Gentlemen of Verona). And the press tore into them again. The Times set the tone, berating ‘that strange disorder of the mind or the eyes which continues to rage with unabated absurdity among a class of juvenile artists who style themselves PRB’. It was shrewd enough to rope two non-members into what it called the ‘Pre-Raphael-brethren’: the artists Charles Collins, who had entered Convent Thoughts, and Ford Madox Brown, who had entered a painting he’d worked on for several years, the shortened title for which was Chaucer Reading the Legend of Custance.

The Last of England by Ford Madox Brown

This time Millais began the fight-back. He was the one best placed to do so; already acknowledged as an up-and-coming artist and young man to watch, Millais had influence. He spoke to his friend Coventry Patmore, a respected poet who held a post of some importance at the British Museum. Patmore knew John Ruskin who, in his early thirties, was the leading critic of the day; his Modern Painters had been an unqualified success, and 1851 saw the publication of his blockbusting Stones of Venice. For Ruskin to write against the tide, as he did, in defence of the Pre-Raphaelites was as unexpected as if Brian Sewell had praised the early works of Damien Hirst. Fellow critics withdrew their daggers and, by August, Hunt’s Sylvia had been judged Best In Show at the Liverpool Academy. Millais became the youngest man ever elected an Associate of the Royal Academy. Their pictures began to sell.

In the following year’s RA Exhibition Hunt and Millais were adjudged its stars. Even Rossetti, who still would not show his work there, was taken up by Ruskin. Rossetti’s brother and F G Stephens switched from practising art to become critics. Woolner emigrated to Australia. It seemed the end of his career, but it was his departure that inspired Madox Brown’s The Last of England. Woolner failed as an emigrant and returned to England a few years later – to find success.

Life around them carried on. In 1854 Britain embarked on the disastrous Crimean War but, at the RA Exhibition where the war was largely ignored and where the climate was more welcoming to the Pre-Raphaelites, Millais exhibited nothing, presumably because he’d become embroiled in a painful marital tangle between himself and Mr and Mrs Ruskin. Stephens had his second and final exhibition (a painting of his mother) and Collinson showed his Thoughts of Bethlehem. But it was Hunt who created headlines: he was applauded for his religious picture, The Light of the World, destined, as no one yet realised, to become the most reproduced painting of the century. Yet at the same time he provoked controversy and a deal of genuine bemusement with his other work, The Awakened Conscience. Critics were divided: it was ‘ … very great … perfectly represented’, exclaimed the Literary Gazette; ‘absolutely disagreeable’, grumbled the Morning Chronicle, and ‘repulsive’, concurred the Athenaeum. Again Ruskin came to its defence. He explained what The Awakened Conscience was about: of all the paintings in the exhibition, he said, ‘there will not be found one powerful as this to meet full in the front the moral evil of the age in which it is painted’. Debate continued. Hunt, seeing the success of his ‘religious picture’, determined that to meet ‘full in the front’ the Pre-Raphaelite ideals of authenticity and truth, he should take himself off to the Holy Land to paint more Bible pictures.

In 1855 and 56, while Hunt laboured abroad and Rossetti followed his own path, it was left to Millais to keep the Pre-Raphaelite flag aloft. His The Rescue was the hit of 1855, and at the 1856 Exhibition he showed a portrait and four major paintings: The Random Shot (concerning the French Revolution rather than the all too recent and painful Crimea); Peace Concluded (which although it was about the Crimea introduced the more sentimental approach he’d apply to future paintings); The Blind Girl (which, if even more tear-jerkingly sentimental, is so well painted as to remain one of his best works); and Autumn Leaves (a beautifully melancholy study of passing time, though with looser paint and unmistakeable signs of post-Pre-Raphaelitism). Now married to the spendthrift Effie, Millais was more concerned at the price his pictures would fetch than with their critical reception: ‘I have already two thousand [guineas] certain in the pictures, and with every hope to make up another in the copyrights and other things,’ he wrote to his wife – and that switch of attention from the critical to the financial shaped the rest of his career.

What, then, was the future for Pre-Raphaelitism? Of its three young founding fathers, Millais was drifting away, Rossetti talked the talk but never really belonged, and Hunt took longer and longer to produce his sporadic paintings. It was time for a second wave of enthusiastic practitioners to beat upon the shore.

1857 saw an exhibition billed as the First Ever Pre-Raphaelite Exhibition. It was organised by Madox Brown in a private house in Fitzroy Square and, as well as Brown himself and the Big Three (Rossetti, Millais and Hunt), the show mustered some twenty-two artists including John Brett, Charles Collins, Arthur Hughes, Robert Martineau, William Bell Scott, Thomas Seddon, Lizzie Siddal and W L Windus. And what pictures! Among others on the walls could be seen Ford’s The Last of England; four from Rossetti: Dante Drawing an Angel in Memory of Beatrice, Dante’s Dream, Mary Magdalen at the Door of Simon and a watercolour of The Annunciation; four pictures from Millais, three from Hunt, and six little pictures from Lizzie Siddal. Sales were modest, reviews we...

Table of contents

- Front Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Introduction

- 1. THE PRE-RAPHAELITES – Back to the Future

- 2. PORTRAITURE – A Good Likeness

- 3. LANDSCAPE – The World About Us

- 4. MARINE PAINTING – Our English Coasts

- 5. GENRE – Work & Everyday Life

- 6. ANIMAL LIFE – The Pretty Baa-Lambs

- 7. HISTORICAL – Great Moments in History

- 8. FOREIGN CLIMES – Religion and Palestine

- 9. NEOCLASSICISM – In the Tepidarium (Now, That’s What I Call a Picture)

- 10. SCULPTURE – Portraits in Stone

- 11. FANTASY & SYMBOLISM – The Fairy Feller’s Master-Stroke

- 12. DECORATIVE & AESTHETIC – Fin de siècle, Still Life, Nudes

- 13. A CENTURY OF BLACK & WHITE – Printmakers, Engravers & Caricaturists

- 14. ILLUSTRATION – Art for the Millions

- 15. ARTISTS AND MODELS – Close Relationships

- Where to see the pictures

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access The Pocket Guide to Victorian Artists & Their Models by Russell James in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Art & Art General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.