eBook - ePub

Marston Moor

English Civil War–July 1644

David Clark

This is a test

Share book

- 192 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Marston Moor

English Civil War–July 1644

David Clark

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Following on from the success of the first book in this series on the English Civil war, Naseby, here is the story of Marston Moor, arguably the most famous battle in the four year conflict.In this exciting analysis of the battle the Author has captured the atmosphere and made it possible to get the most out of the experience. Marston Moor was an extremely bitter and costly battle and a defeat for the Royalist cause that had major implications for King Charles I. One result was that the key city of York was lost thereby seriously weakening the King's grip on the North.

Frequently asked questions

How do I cancel my subscription?

Can/how do I download books?

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

What is the difference between the pricing plans?

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

What is Perlego?

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Do you support text-to-speech?

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Is Marston Moor an online PDF/ePUB?

Yes, you can access Marston Moor by David Clark in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Histoire & Histoire prémoderne. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

HistoireSubtopic

Histoire prémoderneChapter 1

THE CIVIL WAR IN YORKSHIRE

The man was called Richard Wright – or so his descendants claim – and, although apocryphal, the tale does serve to suggest that, despite two years of civil war, no battle sufficiently substantial to engage public attention had yet taken place in the largest county in England. It also reminds us that Yorkshire folk then, as now, were of a distinctly parochial turn of mind, being relatively unmoved by the political and religious radicalism of the time. Indeed, in 1642, as the rift between Charles I and Parliament widened, it was hoped that matters could be resolved elsewhere and that Yorkshire could stand aloof. Yet, from January of that year, Yorkshire Cavaliers and Roundheads were making preliminary preparations for war.

The pattern of support for both sides did not follow hard and fast lines. Generally speaking, however, the poorer, conservative rural areas declared for the King, while the prosperous commercial towns supported Parliament. The rustics had little choice in the matter, usually following blindly in the wake of their landlords. More volatile was the situation in urban areas, where the acquisition of wealth was dependent upon a combination of industry and economic stability, as opposed to privilege. Some businesses, such as iron working, leather working, shipbuilding, lead and coal mining, would derive the usual benefits accruing from a war economy. Other entrepreneurs, less sanguine in their expectations, were prepared to back the side most likely to win or to take the course of action which promised the least disruption to everyday business.

In Hull, for example, several of the leading citizens were ‘famous king's-men’, but their priority was ‘to keep the town in peace and safety’. When Sir John Hotham, for Parliament, appeared at the gates of Hull on 14 January 1642, he was rebuffed by the lord mayor, only to be admitted a few days later when the latter submitted to threats. Hull became the first town to be seized by Parliament – and a most important acquisition it turned out to be, not least because of its mighty arsenal which comprised the better part of 120 field pieces, 20,000 arms and 7,000 barrels of gunpowder.

Certainly, the King overestimated the extent of his subjects’ affection for him – particularly in Yorkshire. While Charles was staying in York, the Cavalier and diarist, Sir Henry Slingsby, was ordered ‘to take 20 of a company to do the duty of a soldier and be a guard to the King's person’. Slingsby records that he ‘perceived a great backwardness in them; and upon Summons few or none appeared.’ A subsequent fund-raising meeting on Heworth Moor ‘produced nothing else but a confused murmer and noise, as at an Election… some crying [for] the King, some [for] the Parliament.’ Many prospective supporters, like Slingsby himself, who lobbied long and hard for commissions, were told that they would be granted only if each recipient undertook to equip a body of men at his own expense.

The man appointed by Parliament to attend to the overall defence of Yorkshire was Ferdinando, Lord Fairfax. Described by his irascible father as ‘a mere coward’, any reputation he subsequently acquired as a commander was destined to be eclipsed by that of his own son, Sir Thomas. The Fairfaxes had hoped for a peaceful solution to the nation's ills and, when he left York, Charles had no reason to doubt their loyalty.

In September 1642, Ferdinando, 2nd Lord Fairfax, was appointed commander of the Parliamentary army in Yorkshire and was largely successful in keeping in check the superior forces of the Marquis of Newcastle

Initially leading the Yorkshire Cavaliers was Henry Clifford, Earl of Cumberland. Even his friends recognised that ‘his genius was not military’, and he was soon replaced by William Cavendish, Earl of Newcastle, one of the wealthiest landowners in the kingdom. Already responsible for Northumberland, Durham, Cumberland and Westmoreland, Newcastle was loathe to take on additional responsibilities. He was expected to outfit and maintain his own men, and although some thought he could well afford it, he demanded financial guarantees before venturing forth. Apparently satisfied, he marched from Northumberland to York, overrunning en route, at Piercebridge, a small Roundhead force led by Captain John Hotham, son of Sir John on 1 December 1642. On his arrival in York, the governor, Sir Thomas Glemham, a committed Cavalier, presented him with the keys of the city.

Most of the fighting in Yorkshire took place in the West Riding, where the Fairfaxes enjoyed widespread support in the clothing towns. The first battle took place at Bradford in October 1642, Sir Thomas Fairfax reporting that his poorly armed force of 300 men bravely repelled an assault by some 700 Cavaliers.

A few weeks later, at Wetherby, Sir Thomas was surprised by an assault force out of York, led by Sir Thomas Glemham. According to the Cavaliers, who attacked at 6.00 am, Fairfax was still putting on his boots when the attack came, although Fairfax claimed he was already astride his horse. Rousing his troops, he repelled two assaults and Glemham was eventually beaten back.

Sir Henry Slingsby, in providing an account of this action, describes a particular incident between a Roundhead, Captain Atkinson, and a Cavalier, Lieutenant Colonel Norton. Atkinson, on horseback, shot at – and missed – Norton as he entered the town. Norton dragged Atkinson from his mount as troops from both sides approached to give aid. Norton was beaten into a ditch while Atkinson suffered repeated blows which broke his thigh, ‘of which wound he died’. Slingsby describes the altercation as ‘A sore scuffle between two that had been neighbours and intimate friends.’ The action was only a skirmish, with a handful of casualties on both sides, but it encapsulates the tragic nature of the conflict.

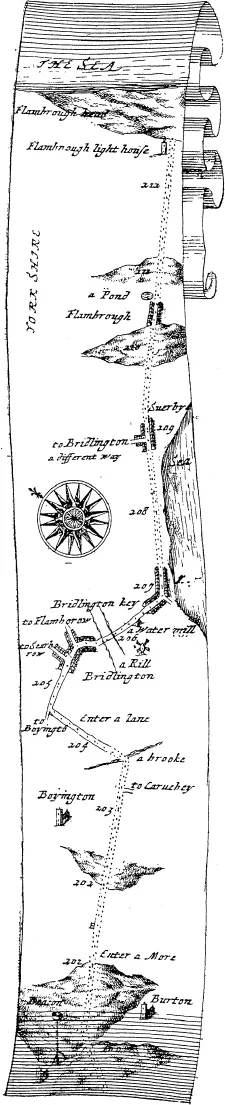

In the seventeenth century, several road maps in scroll form were produced for the use of travellers. Mileage was indicated as were beacons, gibbets, brooks, bridges, churches, mills, moors and commons. The illustration, from a map, produced in 1675 by John Ogilby, depicts Bridlington on the East Yorkshire coast. Even today, this style of mapping is preferred by some ramblers and cyclists.

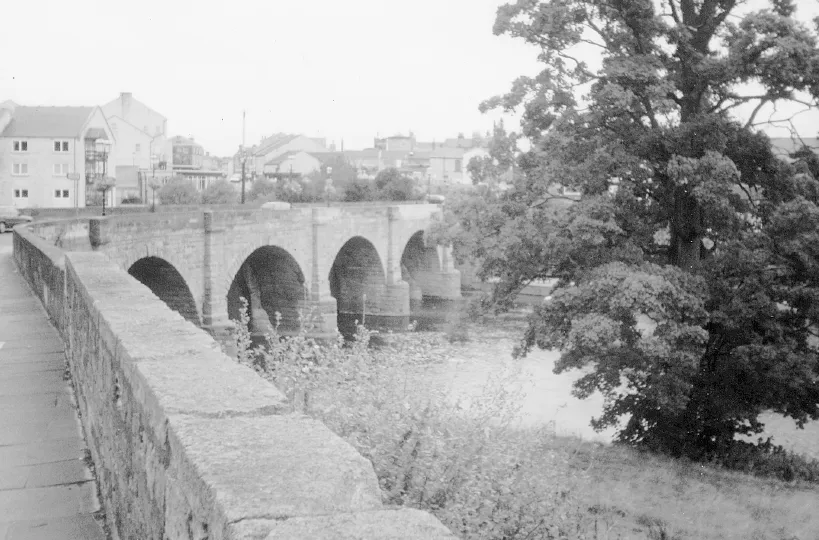

Bridges were the focul points of many battles and skirmishes in the Civil War in Yorkshire. The bridge spanning the River Wharfe at Wetherby was of particular significance owing to its proximity to York.

Sir Thomas Fairfax excelled in such small scale cut-and-thrust affairs, mounting his own guerrilla raids, closely fought encounters within the confines of narrow cobbled streets. With rarely more than a few hundred men under their command, it was not open to the Fairfaxes to do much more. Towards the end of 1642, when Newcastle arrived on the scene with 6,000 troops, they retreated to Tadcaster where, in a fight which raged throughout the afternoon of 7 December, they successfully defended the bridge spanning the River Wharfe.

Short of ammunition, the Fairfaxes had to abandon Tadcaster and fell back on Selby, cutting themselves off from the West Riding. A week later, resolved to take the fight to the enemy, Sir Thomas raided Sherburn-in-Elmet which was held by the Cavaliers. In a typical piece of derring-do, he led his men in a charge along the barricaded main street and had his horse shot from under him before the defenders were put to flight. Cavalier reinforcements forced an orderly retreat to Selby yet, as a result of this minor success, Fairfax later recalled that ‘we lay more quietly by them [the Cavaliers] a good while after.’

In fact, Newcastle was making efforts to secure Leeds, Wakefield and Bradford. In so doing, he was compelled to divide his army. Leeds and Wakefield were occupied and plundered, but Bradford proved a more stubborn nut to crack. On 18 December, Newcastle attacked the town, but met with fierce resistance from apprentice boys armed with a motley assortment of weapons, including fowling-pieces, clubs and scythes, who set up barricades and withstood an artillery barrage. In savage hand-to-hand fighting, the Cavalier assault was repulsed. Here was a town which it seemed the Roundheads could hold, and Sir Thomas was despatched to lend support, being ‘received with great joy and acclamation of the country’.

A string of Yorkshire castles held by the Cavaliers formed a precious lifeline for their cause. One of the strongest was Pontefract Castle, the last Royalist stronghold in England to fall.

Despite successfully defending Bradford from several more attacks, Sir Thomas, disdaining to ‘lie idle’, decided to launch an attack on Leeds. On 23 January 1643, having received a negative response to his summons to surrender, Fairfax stormed the barricades and fought his way into the streets. In the face of such a resolute assault, many of the defenders ‘cast down their arms, and rendered themselves prisoners.’ Also captured was a ‘good store of ammunition.’ Newcastle, who had established temporary headquarters at Pontefract, withdrew to York. Unfortunately, with limited manpower, the Roundhead army was unable to consolidate yet another success, and had no course but to continue its nomadic existence, moving from town to town as the occasion demanded.

Newcastle himself was preoccupied with weightier matters. In February 1643, Queen Henrietta Maria arrived in Bridlington, accompanied by 1,000 mercenaries, a considerable quantity of arms and ammunition and £80,000 in cash – the result of several months spent on the Continent canvassing for support. The Queen's safety became Newcastle's top priority and he marched forty miles to the small fishing port in order to escort her safely to York.

Henrietta Maria's arrival was no secret. Captain John Hotham rode up from Hull to inform Newcastle that he and his father were prepared to change sides for a price – £20,000 to be exact. Newcastle left the matter open while winning an undertaking from Hotham that the Queen would not be molested en route to York. Her convoy of 500 wagons trundled across the Yorkshire Wolds unhindered, to Burton Fleming, Malton and finally York, where she arrived safely on 8 March.

Henrietta Maria was to remain in York for three months, creating a difficult situation for Newcastle who had to afford her the deference demanded by her position while striving to retain his authority in military matters. Her visitors included the Earl of Montrose who needed ‘the king's warrant’ to help him bring to fruition plans for a rising in Scotland in support of Charles. Montrose also warned of the likelihood of a Scottish invasion in support of the Roundheads – an idea which was given little credence. By the time Charles gave Montrose his official blessing, in February 1644, Leven's army was already across the border. Another guest at the King's Manor was Sir Hugh Cholmley, Roundhead governor of Scarborough, who arrived in disguise, with a black patch over one eye. Like the Hothams, he was considering changing his allegiance. Despite his piratical posturing, his intentions were sincere for, less than a week later, while the Hothams wavered, Cholmley announced that, henceforth, he would be holding Scarborough for the King.

Lacking the facilities afforded by a major east coast port, Queen Henrietta Maria, arriving with men and arms from the Continent, was forced to put into Bridlington, where she was reduced to hiding in a ditch.

With the Queen secure, Newcastle was free to resume his pursuit of the Fairfaxes. Thus, at the end of March 1643, in the course of his enforced perambulations, Lord Fairfax, marching from Selby to Leeds, found that Newcastle was once more hot on his trail. In an effort to draw off the Cavalier army, Sir Thomas attacked Tadcaster. Although it bought his father valuable time, he himself was caught out in the open five miles from Leeds, on S...