![]()

Chapter One

The Road to Cassino

On the morning of 15 January 1944, after a long struggle up the peninsula from Salerno, the Americans finally took Monte Trocchio. From summit of this peak the broad flat valley of the Liri River appeared to stretch for miles and it must have seemed to them that they only had to cross the swift Gari River below and the road to Rome was theirs. Sadly this did not prove to be the case. Instead they were facing one of the strongest German defensive positions in Italy, the Gustav Line, thanks to Generalfeldmarschall Albert Kesselring, Commander-in-Chief of Heeresgruppe C in Italy. Unwilling to give up southern Italy so easily, he had managed to convince Adolf Hitler that this was the right strategy and had set up a series of defensive lines across the peninsula, the first of which, the Barbara Line, the Allies had already encountered. The Gustav Line ran along the lower reaches of the Garigliano River to Monte Cassino and because of the strategic importance of the Liri Valley was one that the Germans had put considerable effort into its development.

Just why the Allies invaded Italy in the first place is another matter. The Americans had been against a campaign in what the British Prime Minister, Winston Churchill, termed the ‘soft underbelly of Europe’. Their eyes had always been set on a cross-Channel invasion of France from England. The problem for the Americans was that at the time of their entry into the war they lacked the resources, both in men and materiel, to pursue this aim. Thus they had no choice but to enter the Mediterranean theatre of operations, first in North Africa in support of the British and then in the invasion of Sicily. Neither of these operations were particularly desirable to the Americans but the seizure of the latter did offer the possibility of an alternative route into France, via Sardinia and Corsica.

However, fate intervened after they landed on Sicily, bringing with it a new and unexpected opportunity as it led to the collapse of the regime of the Italian dictator Benito Mussolini. Lacking the courage to continue the war, the new Italian government then entered into secret negotiations with the Allies that ultimately led to an agreement for the Italian armed forces to lay down their arms. The Germans, on hearing of the announcement of the armistice between the Allies and Italy, had moved rapidly to take over the country. In the north Generalfeldmarschall Erwin Rommel’s Heersgruppe B seized the main centres there and disarmed the Italian troops under his command. In the south the Germans had actually intended to withdraw northwards after disarming the Italians, that is until Kesselring successfully argued against this plan. This was partly driven by the impracticality of pulling his troops out without losing too much in the way of men and materiel but also because of the importance of the airfields around Foggia. Instead, after disarming the Italian troops under his command, Kesselring began the construction of a series of defensive lines across the Italian peninsula,

Having had their hands forced the Americans reluctantly agreed to landings on the Italian mainland but only on the understanding that it would help tie down German forces in Italy and secure the airfields around Foggia, the latter for use by their bombers against mainland Europe. The first of these were made in the toe of the peninsula, at Reggio di Calabria, by General Sir Bernard Montgomery’s 8th Army but their progress was slow. These were soon followed by the main assault in the Bay of Salerno by General Mark W. Clark’s US 5th Army on 3 September 1943, then later by landings of British airborne troops at Taranto. The main force at Salerno soon ran into trouble when they encountered bitter opposition as they began to fight their way off the beaches. At one point the German assault threatened to throw them back into the sea. Ironically, more success was had on the Adriatic coast where the British paratroopers, despite the lack of transport, heavy weapons and armour, managed to secure Bari and Brindisi before the area was sealed off by what German troops there were in the region. Eventually the situation at Salerno stabilized and the Allies were free to expand. British troops entered Naples on 1 October, Foggia on the Adriatic falling to paratroopers the same day.

Unfortunately, the lack of a cohesive strategy by the Allies in the Mediterranean started to work against them. With winter fast approaching, the question arose as to what to do next. Given that their principal aims had been to eliminate Italy from the war and tie down the maximum number of German units there, the Allies had succeeded admirably in the first instance. The trouble was that the second was so vague as to be absolutely meaningless. Having secured the vital ports and airfields in the south of the peninsula there was a feeling that they had gained enough to give their naval and air forces control of the southern Adriatic and Ionian seas. On the other hand, though pushing north would give them the access to airfields around Rome, they saw no advantage in areas beyond there. Nevertheless, their successes up to that point had given them hope that an occupation up to the Northern Appenines was possible. There were even advantages to be gained by pushing beyond there and into the plains of the Po River. At their Quadrant Conference in Quebec a general agreement was reached that, while progress in Italy was likely to be slow, Rome was an important objective that should be seized as soon as possible.

At the strategic conference at Teheran at the end of November between Churchill and his Allied counterparts, President Franklin D. Roosevelt of the USA and Josef Stalin of the USSR, an agreement was eventually reached to continue the offensive in Italy. This was despite misgivings on the part of Stalin that the British and Americans had designs on Europe east of Italy. While the main focus of the Americans was in the invasion of northwest Europe, they did agree to a landing in southern France. This in turn strengthened their desire to secure Rome and, in fact, to be well north of it by the spring of 1944 as their intention was to launch their assault on southern France from northern Italy. Thus, whether the Americans liked it or not, they were being drawn deeper into the mire that was to become the Italian campaign.

Before that could happen they needed to secure their hold on Naples and Foggia by establishing a line along the Volturno and Biferno Rivers. Clark’s troops ran up against the former on 6 October, a day before the 8th Army secured Termoli on the Biferno. From here on the British 8th Army found themselves in some tactically ugly terrain where the plains around Foggia gave way to hills cut by rivers running down to the sea.

Things were no better on the other side of the Apennines, as north of the Volturno River the Americans found themselves up against 40 miles of mountainous terrain before they could draw up against the Bernhardt Line along the line of the Garigliano River. Worst still the autumn rains had struck in their full fury, turning the river flats into a sea of mud. In the end Clark’s attack over the Volturno was not launched until 12 October. This forced the Germans to retreat towards their next defensive position, the Barbara Line, the Allies reaching this on 2 November. By early November this too had been breached, the Germans falling back to the Bernhardt Line.

On the Adriatic coast the British 8th Army had to pause along the line of the Trigno River in order to re-group and reorganize their logistics thanks to the poor roads they had to operate over. As a result they were not able to launch their attack until 2 November. However, a day later they had penetrated three miles beyond it, leaving the Germans with no choice but to fall back to the line of the Sangro River. This the 8th Army’s forward elements reached on 9 November.

Back on the Tyrrhenian side of the Apennines and to the north of the Barbara Line the Americans found that the coastal plain was beset by marshes leaving them the only realistic path to the Liri valley along Route 6 through the Mignano Gap. This area was the responsibility of 10 Armee under the command of Generaloberst Heinrich-Gottfried von Vietinghoff-Scheel. Further north defence of the Cassino sector fell to Generalleutnant Fridolin von Senger und Etterlin’s XIV Panzerkorps.

The US 5th Army finally launched its assault on the mountains around the Mignano Gap on 1 December, but the weather ultimately proved their undoing. Fighting continuing until the end of the year when a blizzard forced them to halt their attack, reorganize and replace their losses. Their final offensive to clear the Germans east of the Garigliano was launched on 4 January, ending eleven days later after the Germans withdrew across the river.

Several days later the Corps Expéditionaire Français (CEF), under Général Alphonse Juin, struck out for Sant’Elia from their positions in the mountains to the north of the US 5th Army. Advancing through the mountains they soon found a gap in the German defences to the south of Acquafondata. In the resulting fighting the German mountain troops suffered heavily and to avoid being wiped out were forced to conduct a fighting withdrawal. Pressing home their advantage, the French troops pushed on until they had taken all their objectives. The last, Sant’Elia, was secured on 16 January after being abandoned by the Germans.

The next phase of the advance of the 5th Army called for them to break into the western end of the German Winter Line at Cassino and drive up the Liri Valley. At the same time, on the Adriatic coast, the British 8th Army had been tasked with securing Pescara and from there to swing south-west towards Avezzano with the aim of threatening the German lines of communication. To achieve this 2nd New Zealand Division, who had entered the Italian campaign for the first time, launched their assault across the Sangro River on 18 November. From there they easily took the heights above the river but failed to secure the next ridge, and the town of Orsogna, despite making three assaults. Further east on the coast the Canadians reached the town of Ortona on 20 December, finally taking it after eight days of intense house-to-house fighting against Fallschirmjäger-Regiment 3. However, by now the 8th Army’s offensive had ground to a halt, with no chance of it resuming until the spring.

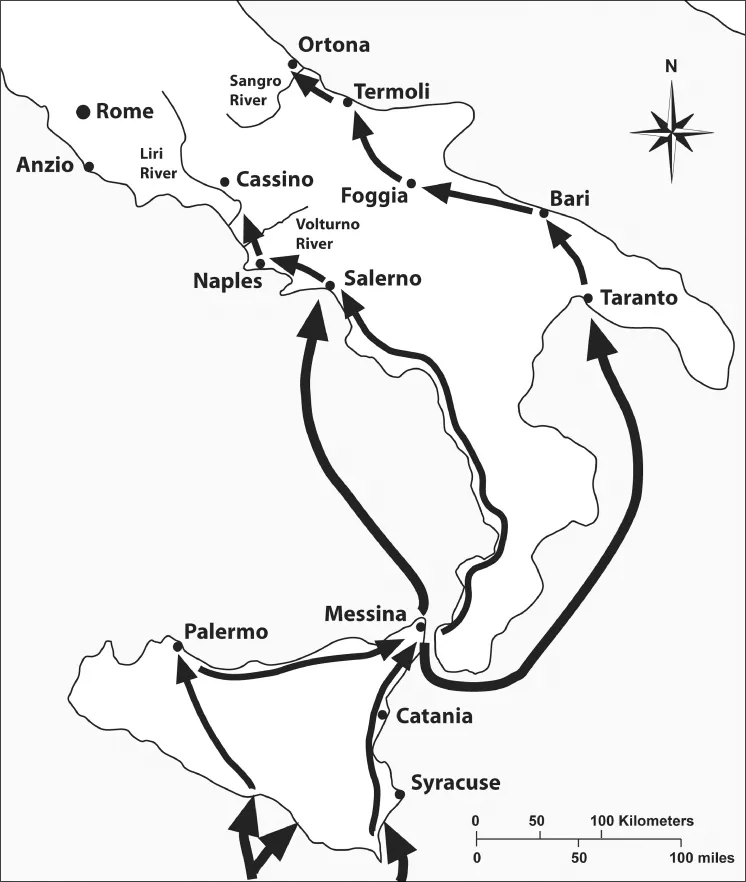

The Invasion of Sicily and Italy.

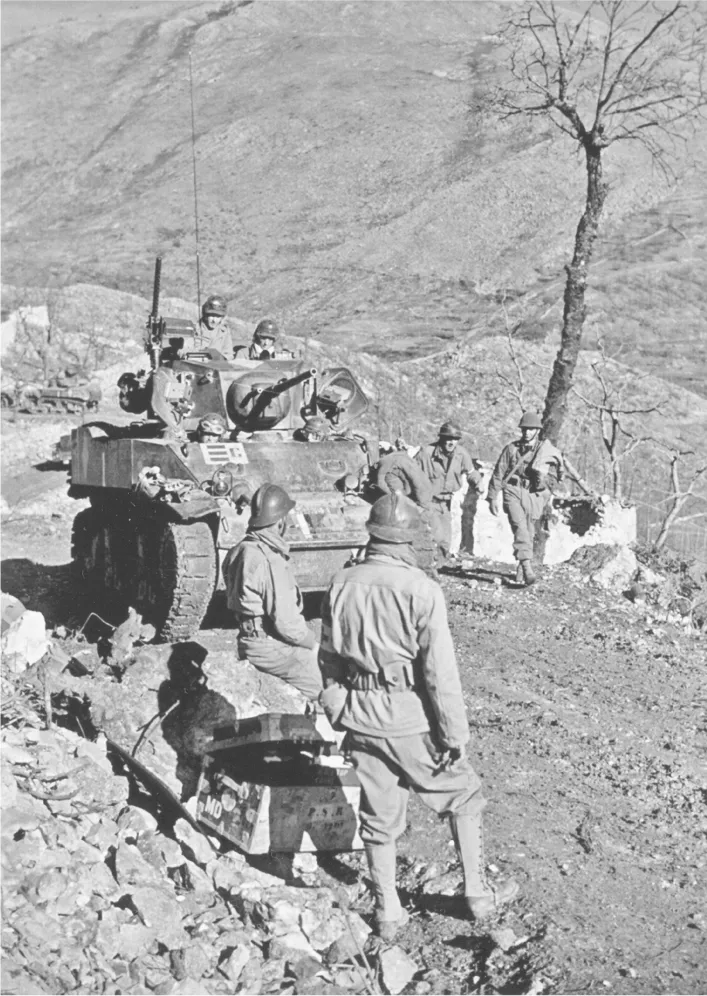

An American soldier inspects a knocked-out StuG III from the Panzer-Division Hermann Göring on Route 6 near San Vittore on 9 January 1944. (NARA)

On 13 January the 3éme Regiment de Spahis Algériens, under the command of Capitaine Henri Spandenberger, entered Acquafondata, part of the column halting in the town itself. (ECPAD)

The rest of the column, including this M5A1 Stuart tank, carried on beyond Acquafondata and halted at this hairpin bend. (ECPAD)

Another M5A1 Stuart tank from the 3éme Regiment de Spahis Algériens was photographed near Acquafondata. (ECPAD)

This M5A1 Stuart tank was photographed just beyond the hairpin bend. (ECPAD)

![]()

Chapter Two

Early Attacks on the Gustav Line

By the end of December 1943 it had become apparent to the Allies that the right hook on the Adriatic coast had failed and if they wanted to reach Rome by June 1944, their only option was an attack up the Liri Valley but there were constraints on this. One of their strategies of opening this door involved a seaborne invasion behind German lines in the Anzio-Nettuno area, codenamed Shingle. This needed to take place before the end of January 1944, as the landing craft and ships required for this would then be withdrawn in readiness for the assault on northern France. As it turned out this ultimately led to the Allies becoming enslaved to the needs of Shingle, initially simply to draw Axis troops south but after the launch of Shingle to break through to the beleaguered troops around Anzio. There were, however, times when their operations seemed to be driven by the need to keep pressure on the Germans in the south to prevent their transfer north to Anzio. One thing the Allies could not stop was the transfer of German troops from the Adriatic coast to the American 5th Army front after it became apparent that Allied operations on the Adriatic were showing signs of winding down, 26 Panzer-Division being the first to go. What the Allies were now facing at the entrance to the Liri Valley was perhaps one of their most formidable German defensive positions in Italy. This was the Gustav Line, a string of defences that coincided with the Bernhardt Line along the lower reaches of the Garigliano but which turned northwards through the Arunci Mountains before passing through Monte Cassino itself.

With Operation Shingle timed to start on 22 January the Allies began their diversionary operations further south in what turned out to be a piecemeal operation. The British, having reached the Bernhardt and Gustav Lines first, began their assault over the lower Garigliano River on the night of 17/18 January. Codenamed Operation Panther, it had mixed results. The leading troops of 56th Division managed to ...