![]()

Chapter One

A Long Way to the ‘Island of Last Hopes’

For over 1,000 years of its long history, the Kingdom of Poland always struggled with its neighbours, being forced to defend its borders against a powerful Germany, Prussia, Russia, Sweden, the Ottoman Empire and Tatars. In the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth (a union of the Kingdom of Poland and Grand Duchy of Lithuania)1 was one of the largest countries in Europe, covering nearly a million square kilometres, with its massive territory stretching from the Black Sea to the Baltic Sea.

It was a country of religious tolerance, with a progressive political system, fast-moving scientific and cultural developments, and the first constitution in Europe that consisted of a set of modern, supreme national laws. The Polish cavalry was famous and almost unbeatable, gaining their reputation by destroying the army of German Teutonic Knights in the Battle of Grunwald in 1410; 2,600 eagle-winged hussars also defeated 10,000 Swedish invaders at the Battle of Kircholm in 1605, while eighty years later, a charge by the Polish army led by King Jan III Sobieski saved Vienna from Ottoman oppression.

However, in the second half of the eighteenth century, the situation for this central European country was much more difficult and far from glorious. Politically divided, weak, surrounded by powerful neighbours hungry for her territory and facing her own internal rebellions, Poland eventually fell. After three consecutive territorial partitions, its existence was ended by the Prussian, Austro-Hungarian and Russian empires. The three titans grabbed what was in their reach, aiming to destroy Polish pride, identity, culture and science. The native Polish language was forbidden, Poland was swept from the map of Europe and her citizens had to wait and fight for 123 years to reclaim their independence.

This finally became possible when the guns of the Great War went silent, Poland regaining her place among other nations in November 1918. The country was free, but definitely not safe, and had to reaffirm its freedom by defending its right to exist and making the Polish borders stronger again. New wars started even before Poland returned to the European map. Two weeks prior to the official proclamation of independence, that became a fact on 11 November, conflict began with the West Ukrainian People’s Republic and Ukrainian People’s Republic (1918-19). This was followed by a decisive war, not fully appreciated by the Western politicians, against Bolshevik Russia (1919-21), when heroic Polish defence crushed the Red Army at the outskirts of Warsaw, and by this act of desperation stopped bloodthirsty communists from marching throughout Europe. While engaged on its eastern flank, the country was invaded by the Czechoslovaks from the south (1919); at the same time, an uprising against German occupation in Greater Poland took place (1918-19), followed by a series of Silesian uprisings (1919-21). Between 1919 and 1920 there was a war against Lithuania, while finally in 1938, Poland was involved in another conflict with Czechoslovakia, both countries claiming their rights to the Zaolzie (trans. Olza Silesia) region.

Years of non-existence as a country or constant movement of its borders made Poland (a ghost country by then) and her citizens a nation of forced travellers. There were several reasons for this. Poles were often obliged to change their place of residence, either as punishment for illegal independence and liberation activity, or, in many cases, when they were looking for a better life and economic stability within the boundaries of the three governing empires, which split the territory of Poland between themselves. That was why those Poles, including the Polish Battle of Britain pilots, who were born prior to November 1918 consequently grew up as residents of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, Prussian then German Empire and Russian Empire before gaining their own citizenship.

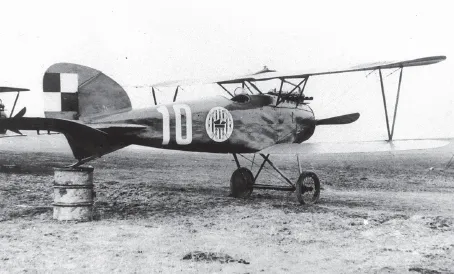

Since regaining her independence Poland had to fight for survival against neighbouring countries. The Polish Military Aviation was born at the same time, although the first encounters noted by the Polish airmen were recorded prior to independence date. Fokker E.V. CWL001 with personal emblem of compass rose and red and white chequerboard, which belonged to Lt. Stefan Stec. The chequerboard had been adopted as an official badge of the Polish Air Force. During the Great War Stec flew with Flik 3/J and then Flik 9/J, gaining three aerial victories. Flying with 7th Squadron (later ‘Tadeusz Kościuszko’ Squadron), Stec added two more claims while fighting against Ukrainians.

Those who were born within the historical boundaries of the former Kingdom of Poland, or whose parents settled in Russia, Ukraine (a state also ruled by the Tsar) or Germany, were still citizens of those empires but of Polish nationality. This is what mainly causes the numerous mistakes made by Western writers who did not experience the movement of borders, or who never lived in the country that was torn apart. The best example of such confusion, which still exists in non-Polish publications, is Squadron Leader Eugeniusz Horbaczewski, introduced in British literature as a ‘Polish-Russian ace’ purely because he was born in Kiev.

The birthplaces of those who were born after the date of Polish independence, but were brought up in towns ruled by Poland, like Wilno (Vilnius since 1945) or Lwów (now Lviv), also cause confusion for Western historians. As a result of the Western powers handing over her future to Stalin after the Second World War, Poland, the first country to fight Nazi aggression, lost a massive part of her Eastern territory, and many of her citizens their homes.

It should not, therefore, be unexpected that, due to the historical turbulences of Poland, her political and geographical instability, which all influenced the mixing of cultures, there were Second World War Polish pilots called Ebenrytter, Henneberg, Goettel, Klein, Langhamer, Mümler or Pfeiffer,2 or, on the opposing side, Germans named Dymek, Guschewski, Kaminski, Kania or Mazurkowski.

During all those struggles, a gradual involvement of the newly born, inexperienced and rather primitive Military Aviation (Lotnictwo Wojskowe) – as officially the future Polish Air Force was called – can be observed. This was a brand new concept and structure that was formed from absolutely nothing. The Polish Military Aviation based its first strength on pioneers, veterans of the Great War who, against their will, served in armies of occupation of the Russian, German and Austro-Hungarian empires, and very often had no other choice than to fight against each other.

These soldiers with no country now gained back their Polish citizenship and learnt how to keep their heads held high. At this point, in utterly new circumstances with limited resources, they had to build a completely new flying arm of the military system, and had to do it quickly, as the enemies of the Second Polish Republic did not want to wait. Like an ancient phoenix rising from the ashes, Poles generated their early air force by using damaged, incomplete or not fully efficient equipment that was left by their former tyrants and oppressors.

Challenges piled up rapidly. Spare parts were desperately needed. Polish industry had been ruined and plundered, and too few skilled personnel were available. There was, however, no lack of enthusiasm or passion. Against all odds, the Polish Air Force was making small steps and getting ready for combat.

Unfortunately, from the moment of its birth the Polish Military Aviation suffered from the Great War syndrome. Veterans of the previous conflict, who remembered flying over the trenches and performing reconnaissance missions, were now in charge. People who did not see how aerial conflict could easily develop, in their minds labelled aircraft as of secondary importance. They were supported in their naivety by the head of the Polish state, Marshal Józef Piłsudski, who strongly believed that in forthcoming conflicts the aviation would only be used over battlefields as a reconnaissance force, in a supporting role to the main power – the army. Piłsudski kept saying that ‘aviation is to serve only for reconnaissance purposes and only in this direction should it be used’. Hence, liaison/companion or army co-operation squadrons (Eskadras) were favoured and dominated, and at some point training of military officer pilots had been restricted to only produce more observers. It was like teaching an old dog new tricks, but in this casee the teachers were difficult to find.

An interwar period that Poles themselves rather optimistically called ‘twenty years between wars’, which was dated from the Armistice of 11 November 1918 that concluded the Great War and ended by German aggression in 1939, had in fact been much shorter, interrupted by the previously mentioned conflicts. Therefore, Polish aviation infrastructure had only very limited time to develop properly before the outbreak of the Second World War. This was not helped by poor budgetary and industrial capability and lack of certainty of the future role of the military aviation, with inadequate plans.

Nevertheless, there was no lack of admiration for this newly born military arm of the Polish defence system. Personnel training expanded rapidly. Thousands of enthusiastic young men joined civilian gliding training, and various air force schools were formed, including the famous Polish Air Force Cadet Officers’ School in Dęblin, fairly considered as one of the best aviation academies in the world. Flight Lieutenant Stanisław Bochniak, who earned his wings in Dęblin and later flew operationally in Britain, said:

Albatros D.III of the 7th Fighter Squadron photographed during the Polish – Bolshevik war in 1920. The “Kościuszko” badge designed by Lt Elliot Chess, an American volunteer, can be seen.

‘There was a popular saying amongst the aviators that only thanks to us was the Finger Formation called the Polish Formation. [It was a] quite difficult structure, which required a huge amount of skills, which we did not lack by then. This unique aerial arrangement allowed us to watch after each other and to fly safely. English pilots could not understand and adopt such a formation for a very long time. We owed such skills to the Eaglets School at Dęblin, beyond doubt, the best aviation school in the world.’3

The 1930s saw an impressive reorganization and intensification of flying training in Poland, while aviation engineering was also improved drastically. In 1939, about 800 pupils were in training in Dęblin and over 300 highly trained cadet officers graduated from this school, 65 per cent of them pilots. Needless to say, Dęblin was only one of the educational elements of the Polish air force chain: there were also Technical and NCO schools.

Although the Polish Military Aviation largely based its strength on French-built or licensed equipment, indigenous technological progress blossomed too. The Polish, or better known as Puławski wing, wing of the gull shape marked a brand new era by boosting Polish industry and outperforming other contemporary fighters across the world. Zygmunt Puławski’s design turned into the first totally metal-built fighter aircraft. The P.6 model created an absolute sensation when shown in Paris and then in Ohio, USA, and its successor in 1934, the P.24, was announced as the fastest and best-armed fighter aircraft in the world. Jerzy Rudlicki of the LWS factory in Lublin created a revolutionary Vee-tail unit that was later copied by many other countries.

These are just two out of many examples. All this development was undoubtedly ignited by the success of Captain Stanisław Skarżyński, who made a tour across Africa flying the Polish-built PZL Ł2, and soon after crossed the Atlantic in a RWD-5bis. Poland in the 1930s also blossomed with the success created by the duo of Franciszek Żwirko and Stanislaw Wigura who won the Challenge 1932 for domestic production aircraft with the RWD 6, while Captain Jerzy Bajan repeated their success two years later and also flew a Polish aircraft.

Unfortunately, what was considered a great success at the beginning of 1930s was already obsolete just a few years later, lagging far behind the competition. In the mid-1930s, low-wing aircraft with retractable undercarriage, fully enclosed cockpit and metal wings appeared as standard. The British Spitfire (despite going into production relatively late), French Morane 406 and German Messerschmitt 109 were not only much faster than Polish planes, but also had an advantage of decisive gun power. Not only was the only Polish front-line fighter and interceptor monoplane, the PZL P.11, with a maximum speed of 233mph and armament of two 7.92mm machine guns, no match for the German Messerschmitt Bf 109 or Bf 110, but its performance also placed this aircraft behind Luftwaffe bombers such as the Dornier Do 17, Heinkel He 111 or Junkers Ju 88.

The group of Cadet officers of the 11th class of the Polish Air Force Cadet Officers’ School at Dęblin (please note school’s badge on their singlets). Amongst them are some future Battle of Britain pilots. Front row, from left to right: Jan Daszewski (1st), Aleksy Żukowski (2nd), Tadeusz Nowak (4th) and Jerzy Czerniak (6th). Back row: Włodzimierz Samoliński (1st).

In 1936, Poland finally began development plans, but the results were not impressive. Due to controversial decisions at various levels and key departments, who were playing a blame game, these plans had no chance of being implemented. The best Polish fighter plane, the PZL P.24, with two Oerlikon 20mm cannons and two machine guns (or four machine guns), were exported to Bulgaria, Turkey and Greece. At the same time, the PZL P.50 ‘Jastrząb’ (Hawk) was still undergoing trials and far from entering final production, similar to the twin-engine PZL P.38 ‘Wilk’ (Wolf), a disappointing interceptor and fighter-bomber. Others, such as the PZL P.45 ‘Sokół’ (Falcon) and PZL P.48 ‘Lampart’ (Leopard), were mostly only on the drawing board or taking shape as prototypes. Sadly, in September 1939, the PZL P.11, the lonely defender of Polish skies, had been left only with its remaining advantages of manoeuvrability, robustness and agility; and of course with highly trained and brave pilots inside their cockpits.

![]()

Chapter Two

Myths and Understatements

‘I remember 1 September 1939 very clearly, for how could any Polish person ever forget,’ wrote Jan Kowalski, instructor of the Air Force NCO School for Minors and future Battle of Britain pilot.

‘I was asleep and suddenly awoken at 6.30 am by the sound of aircraft approaching. I knew that it was not our aircraft as none went up until after 8 am. Within seconds, the German aircraft were dropping bombs all around us. We quickly ran to the trenches that had only recently been dug out. Three rows of buildings, the mess, living quarters, and hangars were all hit.’1

How many times have various books and historical magazines, published in the West, portrayed, unsupported by any facts, the subject of Polish cavalry armed with just lances and swords, but also with romantic heroism yet tremendous stupidity, charging against German tanks?2 Another myth created by Nazi propaganda that is still widely believed today, without any proof to back it up, is that the Polish Air Force was destroyed almost immediately on the ground, and that the entire Polish Campaign of 1939 lasted only days, followed by the mass escape of Polish forces across the borders into Rumania and Hungary.

Many biographies of the Polish airmen written in English will contain the phrase ‘escaped to Britain’. Unfortunate word of ‘escape’ (in Polish language directly translates to ‘running away’) thoughtlessly misused so often, makes the Polish military per...