- 136 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

When a large group of rebels invaded Angola from a recently independent Congo in 1961, it heralded the opening shots in another African war of independence. Between 1961 and 1974, Portugal faced the extremely ambitious task of conducting three simultaneous counterinsurgency campaigns to preserve its hegemony of Angola, Portuguese Guinea and Mozambique. While other European states were falling over themselves in granting independence to their African possessions, Portugal chose to stay and fight despite the odds against success.That it did so successfully for thirteen years in a distant multi-fronted war remains a remarkable achievement, particularly for a nation of such modest resources. For example, in Angola the Portuguese had a tiny air force of possibly a dozen transport planes, a squadron or two of F-86s and perhaps twenty helicopters: and that in a remote African country twice the size of Texas. Portugal proved that such a war can be won. In Angola victory was complete.However, the political leadership proved weak and irresolute, and this encouraged communist elements within the military to stage a coup in April 1974 and lead a capitulation to the insurgent movements, squandering the hard-won military and social gains and abandoning Portugals African citizens to generations of civil war and destitution.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Angolan War of Liberation by Al J. Venter in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & 20th Century History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1. UNFOLDING

4 February 1961

A small group of Africans, all linked to the political group Movimento Popular de Libertação de Angola (MPLA) attacked Luanda Prison. This political grouping was originally established in the pre-1960s when the tiny underground Angolan Communist Party (PCA) linked up with liked-minded dissidents.

The Portuguese initially had 8,000 men in Angola when the 1961 attacks occurred: roughly 3,000 Portuguese military and security personnel (including police) and 5,000 Africans, but this figure is deceptive as this tiny combined force had to control events in a country a dozen times larger than the size of Portugal.

Lisbon’s colonial war (Guerra Colonial Portuguesa), also known in Portugal as the Overseas War (Guerra do Ultramar) and among the guerrillas as the War of Liberation (Guerra de Libertação) was a long, drawn-out and extremely bitter campaign from the start, but the insurgents, having battled almost to the gates of Luanda lost their initial momentum and were gradually pushed back into the jungle.

MPLA guerrilla leader Agostinho Neto reviews his troops.

What was surprising about this jungle war was that there were not many more ambushes.

The Portuguese initially reacted to the uprising with great violence. Many of their own people had been slaughtered—roughly 400 settlers within the first few weeks of the uprising. Local Portuguese communities quickly organized themselves into vigilante committees, and for several months after the violence started, reprisals went uncontrolled by civilian and military authorities. Whites’ treatment of Africans was every bit as brutal and arbitrary as that of the rebels toward them. Fear pervaded the country for a long time, driving an even deeper wedge between the races. The number of Africans who died as a result of the 1961 uprisings has been estimated as high as 40,000, many of whom succumbed from disease or famine. Apart from Europeans killed, hundreds of assimilados and Africans deemed sympathetic to colonial authorities were also slaughtered.

By the summer of 1961 the Portuguese had reduced the area controlled by the rebels to about a half its original extent, but major pockets of resistance remained. Portuguese forces, relying heavily on air power, attacked villages. The result was the mass exodus of Africans toward the Congo.

From then on, with Lisbon pushing its air force and more troops into the hostilities, the struggle became one of grinding attrition and went on for thirteen years. The end of the war came suddenly with an army mutiny—the Carnation Revolution— launched by dissident young officers in Lisbon in April 1974.

18 March 1967

There were thousands of incidents that characterized the nature of the guerrilla struggle that started when a large group of insurgents crossed the border from the Congo, itself in a state of revolt with little and—in some areas—no effective government. The invasion was not coordinated and had no fixed objective apart from killing Portuguese farmers, administrators, traders and residents in a string of small towns scattered about a region half the size of Britain. Government troops arrived soon afterward, but their efforts were fruitless: a handful facing a much bigger rebel force. From there, hostilities escalated as thousands more revolutionaries entered northern Angola and rampaged, seemingly with nothing to stop them striking hard, as far south as Luanda, the capital.

The Dembos, northern Angola: 1967

The Dembos was the focus of much of the insurgent activity in northern Angola in the early days of the war. This heavily foliated, and largely mountainous jungle region starts roughly seventy kilometres north of Luanda. The terrain is rugged, broken sporadically by grey-blue granite peaks and, apart from isolated farmland and local towns and villages, most of it totally undeveloped. The insurgents used the peaks as observation points. The only way into the region during the earlier phases was a single road leading north out of Luanda, but this was poorly maintained and unsur-faced. As a consequence, military road convoys—to which civilian trucks would be attached—had a difficult time because the insurgents were active. It could take a day or more to cover a hundred kilometres by vehicle, twice that in the rainy season. An outward convoy might be attacked four or five times; the return trip was worse because the insurgents would be more prepared, having observed the trucks coming through on the outward leg. Soviet landmines were laid on all roads and tracks to disrupt traffic from the early days of the revolution.

Sector A

Setting: northern Angola lay just north of Sector/Comsec D (and the Dembos mountains). This region stretched all the way to the Congo border and the coast to the west of Matadi, the main Congolese port on the great river. It was a wild, primitive and difficult area, much of it jungle swampland. Malaria and other tropical illnesses were rife. The sector was virtually uninhabited and the few Africans that remained tended to avoid both the Portuguese and insurgents because they simply did not want to get involved in the killings.

To reach Sector D the insurgents travelled either from Congo-Brazzaville or Leopoldville (later Kinshasa) and had to traverse Sector A, which lay flush with the frontier. It took the average insurgent six weeks to cover the 200-kilometre trail. They carried everything needed for the war on their backs—guns, ammunition, explosives, food, medical supplies, landmines and propaganda leaflets—which also suggests that the invasion was not as spontaneous as government opponents would have liked to believe. Eventually they were hauling in 250kg aerial bombs on litters, carried between four or more men (not that these made good for mine-laying as the security forces spotted them easily).

Sector D

Setting: Comsec D, Dembos mountains lay at the heart of the Portuguese counter-insurgency campaign in northern Angola. The sector was about the size of Cyprus and Santa Eulalia camp was its headquarters. There were seven other Portuguese camps in the sector, including Zala to the north of the sector, Zemba in the south and Nambuangongo (‘Nambu’) toward the centre, as well as Quicabo camp.

Sector F

Sector F adjoined Sector D and the Dembos. Terreiro was a small coffee-producing area in Sector F, just north of Santa Eulalia.

Santa Eulalia camp

The headquarters of Comsec D was constructed soon after the 1961 attacks. The camp straddled a group of low-lying hills and was built within what had once been a successful coffee estate. Around the camp was a patchwork of thousands of rows of coffee bushes, offset by open grassland along the perimeter, and beyond the plantation, the jungle. Garrisoned by 300 men, the commander at the time of the author’s visit in 1969 was Brigadier Martins Soares. He had six staff officers to help cope with the counterinsurgency.

The layout of Santa Eulalia was typical of most Portuguese camps in Angola. The perimeter was a two-metre, barbed-wire double fence. Arc lights with protective wire coverings were spaced every three or four metres, but at night their lights could only penetrate fifty or so metres beyond the fence line because of foliage overhang. There were half a dozen machine-gun turrets spread about along the camp perimeter. The central part of the camp had a row of low prefabricated wooden bungalows. An elaborate (by African standards) bunker and tunnel system supplemented these defences. The tunnels meant it was possible to move between the buildings and some of the forward positions in relative safety.

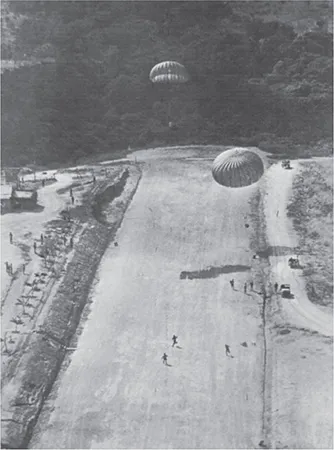

Airdrop onto a remote camp in the Dembos.

Unlike most other jungle camps in the region, Santa Eulalia had a second section near the airstrip for air force personnel. The army provided security for this as well as its own emplacements.

The garrison was highly mobile and provided tactical support for other Portuguese army units in the area. Their mobility came from the two dozen trucks—mostly West German-built Unimogs—as well as helicopters that routinely touched down at the base. Portuguese Air Force Alouette III helicopters all operated from a central base adjacent to Luanda’s main international airport and rarely overnighted in the interior except in emergencies.

Nambuangongo (‘Nambu’) camp

Nambuangongo (‘Nambu’) camp was situated on a modest mountain in Sector D. It had been the officially declared insurgent headquarters in 1961 and fighting in the area had been fierce and consistent from the start. Portuguese army and police losses in the area were relatively high. Retaking Nambuangongo by government troops had been a “significant moral and military victory” for the government, so the insurgents constantly attacked the camp.

‘Ambush Alley’ on the way to the Dembos.

Quicabo camp

Quicabo was a Portuguese camp in the Dembos mountains of northern Angola with a garrison of 200 men. Because of the difficulty of road transport Quicabo got most of its supplies by air. Portuguese Air Force Nord Noratlas supply planes normally dropped their loads from around two hundred metres, with the final approach just above tree level. Once over the camp the transporters would make several passes and make their drops, usually two pallets at a time. The first had the mail, considered the most important cargo. Other supplies were fresh provisions for two or three days plus medical supplies. The terrain was difficult but occasionally the insurgents would attempt to target the aircraft on approach.

Zemba camp

Zemba army camp lay about twenty kilometres southeast of Santa Eulalia. It was overlooked by a large bald sugarloaf mountain to its south: the insurgents sometimes used it or the surrounding bush to fire into the camp or at aircraft, and, indeed, the camp came under attack just about every week since the start of operations. The garrison was composed mostly of infantry and patrolled the area either on foot or in trucks for which it had about a dozen Unimogs. The men followed a set patrol rota: so many days out (until dark) followed by a day or two of rest. The insurgents referred to the Portuguese patrols as ’death walkers’ because the casualty rate was above average compared to other bases in the region. Lying south of the Dembos, there was more grassland than jungle, which, I was told by the commander, made insurgent ambushes less likely.

Fuzileiros (marines) patrol in Congo mangrove swamps.

Portuguese-aligned civilians and local security in Sector D

By 1969 the local Africans of the Dembos generally worked their fields or settler plantations during the day and moved closer to the Portuguese camps for protection at night. The men were armed and organized into platoons under a section leader who reported to a Portuguese officer.

Even with the war, Sector D nurtured fairly large coffee estates, but because free movement could sometimes be dangerous, farmers struggled to hold back the jungle and some plantations were gradually overgrown. No soldiers were stationed in the fields. All farm owners and workers, white and black, were, within reason, responsible for their own security and all were armed with automatic weapons provided by the military. Farmers could fight off small insurgent attacks without help and were in radio contact with the nearest camp if it was felt that more firepower was needed.

Insurgents in Sector D

In 1969 the Portuguese estimated there were an estimated 5,000 to 6,000 insurgents in Sector D. Almost all h...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- CONTENTS

- Glossary

- Introduction

- 1. Unfolding

- 2. What Went on in Portugal’s African Wars

- 3. The Land War

- 4. The Enemy: Divergent Options

- 5. Journalists

- 6. The Air War

- 7. Portugal’s Commandos

- 8. The War in the East

- 9. Cabinda: Tiny Enclave Across the Congo

- 10. Why the War Went the Way it Did

- Bibliography

- About the Author

- Plate section