![]()

1

The Inspiring Idea of the Common School

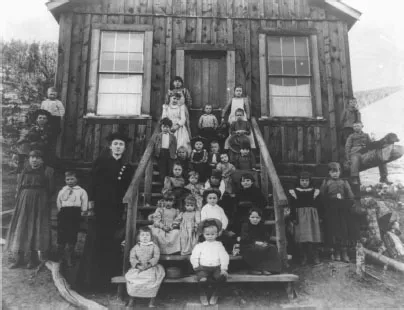

In a picture in the Library of Congress entitled “The Common School,” taken in 1893, you can just make out the face of the teacher, Miss Blanche Lamont of Hecla, Montana, wearing a sweet, ironic smile. For the photo she has perched some boys (and a dog) up on the support logs, and she has given a prominent place to the young boy in the front with the big hole in the knee of his pants.

Miss Lamont seems to be a person who might encourage vigorous recess and mix some fun into the rigorous tasks of the common school. These might have included exercises from the spelling books of Noah Webster, such as “What is a noun? A noun is the name of a person, place or thing,” and edifying stories such as that of the gored ox. Other stories might have come from William H. McGuffey’s Eclectic Readers. The multiplication table and other math facts and procedures might have been taken from the books of Warren Colburn. History lessons might have been based on Salma Hale’s History of the United States, which, like other history books of the time, aimed “to exhibit in a strong light the principles of religious and political freedom which our forefathers professed ...and to record the numerous examples of fortitude, courage, and patriotism which have rendered them illustrious.” From other popular textbooks Miss Lamont would have taught the children art, music, penmanship, and health. All across the nation in 1893, whether in a quick-built gold-rush town like Hecla (now a ghost town) or in the multi-classroom schools of larger towns, American children were learning many of the same things. America had no official national curriculum, but it had the equivalent: a benign conspiracy among the writers of schoolbooks to ensure that all students would learn many of the same facts, myths, and values and so grow to be competent, loyal Americans.1

Miss Blanche Lamont and the Common School of Hecla, Montana, 1893. Courtesy Library of Congress

Since this country was founded it has been understood that teachers and schools were critical to the nation’s future. In our own era, worried policy makers have fixed their eyes on our underperforming schools and devised new laws and free-market schemes to make our students more competent participants in the global economy. There is understandable anxiety that our students are not being as well trained in reading, math, and science as their European and Asian counterparts. Reformers argue that these technical problems can be solved, and they point to exceptional islands of excellence among our public schools even in the midst of urban poverty. But the worries of our earlier thinkers about education would not have been allayed by such examples and arguments. The reason that our eighteenth-century founders and their nineteenth-century successors believed schools were crucial to the American future was not only that the schools would make students technically competent. That aim was important, but their main worry was whether the Republic would survive at all.

It’s hard for us to recapture that state of mind, but it is instructive to do so. The causes of our elders’ concern have not suddenly disappeared with the emergence of American economic and military power. Our educational thinkers in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries saw the schools as the central and main hope for the preservation of democratic ideals and the endurance of the nation as a republic. When Benjamin Franklin was leaving the Constitutional Convention of 1787, a lady asked him: “Well, Doctor, what have we got?” to which Franklin famously replied: “A Republic, madam, if you can keep it.”

This anxious theme runs through the writings of all our earliest thinkers about American education. Thomas Jefferson, John Adams, James Madison, and Franklin and their colleagues consistently alluded to the fact that republics have been among the least stable forms of government and were always collapsing from their internal antagonisms and self-seeking citizens. The most famous example was the republic of ancient Rome, which was taken over by the unscrupulous Caesars and destroyed by what the American founders called “factions.”2 These were seen to be the chief danger we faced. Franklin and Benjamin Rush from Pennsylvania, and Madison, Jefferson, and George Washington from Virginia and their colleagues thought that a mortal danger lay in our internal conflicts—Germans against English, state against state, region against region, local interests against national interests, party against party, personal ambition against personal ambition, religion against religion, poor against rich, uneducated against educated. If uncontrolled, these hostile factions would subvert the common good, breed demagogues, and finally turn the Republic into a military dictatorship, just as in ancient Rome.

To keep that from happening, we would need far more than checks and balances in the structure of the national government. We would also need a special new brand of citizens who, unlike the citizens of Rome and other failed republics, would subordinate their local interests to the common good. Unless we created this new and better kind of modern personality we would not be able to preserve the Republic. In The Federalist No. 55, Madison conceded the danger and the problem: “As there is a degree of depravity in mankind which requires a certain degree of circumspection and distrust: So there are other qualities in human nature, which justify a certain portion of esteem and confidence. Republican government presupposes the existence of these qualities in a higher degree than any other form.”3

Our early thinkers about education thought the only way we could create such virtuous, civic-minded citizens was through common schooling. The school would be the institution that would transform future citizens into loyal Americans. It would teach common knowledge, virtues, ideals, language, and commitments. Benjamin Rush, a signer of the Declaration of Independence, wrote one of the most important early essays on American education, advocating a common elementary curriculum for all. The paramount aim of the schools, he wrote, was to create “republican machines.”4 George Washington bequeathed a portion of his estate to education in order “to sprd systemactic ideas through all parts of this rising Empire, thereby to do away local attachments and State prejudices.”5 Thomas Jefferson’s plan for the common school aimed to secure not only the peace and safety of the Republic but also social fairness and the best leaders. He outlined a system of elementary schooling that required all children, rich and poor, to go to the same school so that they would get an equal chance regardless of who their parents happened to be. Such notions about the civic necessity of the common school animated American thinkers far into the nineteenth century. In 1852 Massachusetts became the first state to make the common school compulsory for all children, and other states followed suit throughout the later nineteenth century. The idea of the common school dated back much earlier in Massachusetts, and in 1812 New York State passed the Common School Act, providing the basis for a statewide system of public elementary schools.6

By the phrase “common school” our early educational thinkers meant several things. Elementary schools were to be universal and egalitarian. All children were to attend the same school, with rich and poor studying in the same classrooms. The schools were to be supported by taxes and to have a common, statewide system of administration. And the early grades were to have a common core curriculum that would foster patriotism, solidarity, and civic peace as well as enable effective commerce, law, and politics in the public sphere.7 The aim was to assimilate not just the many immigrants then pouring into the nation but also native-born Americans who came from different regions and social strata into the common American idea. Abraham Lincoln, who was to ask in his most famous speech whether any nation conceived in liberty and dedicated to equality could long endure, made the necessity of republican education the theme of a wonderful early speech, “The Perpetuation of Our Political Institutions,” given in 1838, long before he became president. The speech echoes Madison and Franklin in stressing the precariousness of our republic. In order to sustain the Union, Lincoln said, parents, pastors, and schools must diligently teach the common American creed.

It’s illuminating to read the Lincolnesque speeches of the state education superintendents and governors of New York in the early and mid-nineteenth century. Like Madison and Lincoln, these New Yorkers understood that the American political experiment, which left everyone undisturbed in their private sphere, depended on a common public sphere that only the schools could create. New York State, with its diversity of immigrants and religious affiliations, was especially alert to the need to build up a shared domain where all these different groups could meet as equals on common ground. The speeches of the state’s governors and state superintendents are filled with cautionary references to the South American republics, which were quickly collapsing into military dictatorships. Unless our schools created Americans, they warned, that would be our fate. As Governor Silas Wright said in his address to the legislature in 1845:

On the careful cultivation in our schools, of the minds of the young, the entire success or the absolute failure of the great experiment of self government is wholly dependent; and unless that cultivation is increased, and made more effective than it has yet been, the conviction is solemnly impressed by the signs of the times, that the American Union, now the asylum of the oppressed and “the home of the free,” will ere long share the melancholy fate of every former attempt of self government. That Union is and must be sustained by the moral and intellectual powers of the community, and every other power is wholly ineffectual. Physical force may generate hatred, fear and repulsion; but can never produce Union. The only salvation for the republic is to be sought for in our schools.8

As early as 1825, the New York legislature established a fund to secure common textbooks for all of the state’s elementary schools, specifying that “the printing of large editions of such elementary works as the spelling book, an English dictionary, a grammar, a system of arithmetic, American history and biography, to be used in schools, and to be distributed gratuitously, or sold at cost.” The aim, they said, was not to “make our children and youth either partisans in politics, or sectarians in religion; but to give them education, intelligence, sound principles, good moral habits, and a free and independent spirit; in short, to make them American free men [and women] and American citizens, and to qualify them to judge and choose for themselves in matters of politics, religion and government...[By such means] education will nourish most and the peace and harmony of society be best preserved.” Exactly the same sentiments animated the great writers of our earliest textbooks, including Noah Webster and William Mc-Guffey. They aimed to achieve commonality of language and knowledge and a shared loyalty to the public good.9

Out of these sentiments emerged the idea of the American common school. The center of its emphasis was to be common knowledge, virtue, skill, and an allegiance to the larger community shared by all children no matter what their origin. Diverse localities could teach whatever local knowledge they deemed important, and accommodate themselves to the talents and interests of individual children; but every school was to be devoted to the larger community and the making of Americans. By the time Alexis de Tocqueville toured the United States in 1831 and wrote his great work, Democracy in America, this educational effort was bearing fruit. Tocqueville took special note of how much more loyal to the common good Americans were than his factious fellow Europeans.

It cannot be doubted that in the United States the education of the people powerfully contributes to the maintenance of the democratic republic. That will always be so, in my view, wherever education to enlighten the mind is not separated from that responsible for teaching morality...In the United States the general thrust of education is directed toward political life; in Europe its main aim is to fit men for private life...I concluded that both in America and in Europe men are liable to the same failings and exposed to the same evils as among ourselves. But upon examining the state of society more attentively, I speedily discovered that the Americans had made great and successful efforts to counteract these imperfections of human nature and to correct the natural defects of democracy.10

Today, every political poll indicates that most Americans believe the country is headed in the wrong direction—in many domains. Hoping to recover our roots, many have turned to the Founding Fathers and looked to them for guidance. Unexpectedly, I find myself doing so as well. It has taken me many years in the vineyard of educational reform to understand how American education lost its bearings. Some of this book is concerned with telling that larger story. A smaller part is concerned with my own twenty-five-year odyssey in the trenches of educational reform, during which I gradually came to recognize the true outlines of the story. To remain ignorant of that history is to remain trapped within it. What John Maynard Keynes said about economic policy applies equally to education: “Practical men who believe themselves to be quite exempt from any intellectual influence are usually the slaves of some defunct [theorist].”11 We need to break out of the enveloping slogans that hold us in thrall.

The Public Sphere and the School

On PBS’s NewsHour with Jim Lehrer a young Muslim woman in a headscarf, aged sixteen or so, was being interviewed. She was speaking earnestly about the Muslim community in the United States, and she was making a lot of sense. What most engaged my attention, however, and still grips my memory was her manner. This girl sounded just like my sixteen-year-old granddaughter. Her intonations were the same, and the smart, smiling, good-natured substance of what she was saying sounded just like dear Cleo—her vocabulary larded with “awesome” and “fantastic” and other enthusiastic expressions of the current youth argot. I thought: this girl is wearing a headscarf, but she is American to the core. I also thought about the ongoing controversy in France, where the government has barred Muslim girls from wearing head-scarves to school. I do not doubt that this American girl wore her headscarf to her public school, and I would be surprised if anybody made a big deal about it. Friends have explained to me why France—another democracy, created a little later than ours in the eighteenth century—is now making such a fuss about Muslim girls wearing headscarves to school. I understand their explanations, but I think that France has failed to learn important principles from its own philosophers and our brilliant American Founders. Our schools and our society may not be doing as well as they should, but they are still doing some things right.

But how deep did this Muslim teenager’s sense of solidarity with other Americans run? In a pinch, would she be more loyal to her religion and ethnic group than to her country? We always hope that none of us will ever have to make such a choice. In the United States we almost never have to, thanks to the political genius of America’s Founders, together with the accident that they lived at the height of the Enlightenment, when principles of toleration and church-and-state separation were at the forefront of advanced thought. How deeply did she understand and admire those ideas? How well had she been taught the underlying civic theory of live and let live that, in human history, has proved to be the most successful political idea yet devised to enable people of different tribes to live together in safety and harmony? My guess, based on consistent reports of our students’ lack of civic knowledge, is that she had not been taught very well.12

A lack of knowledge, both civic and general, is the most significant deficit in most American students’ education. For the most part, these students are bright, idealistic, well meaning, and good-natured. Many are working harder in school than their siblings did a decade ago. Yet most of them lack basic information that high school and college teachers once took for granted. One strong indication that the complaints of teachers are well founded is the long-term trend of the reading ability of twelfth graders, as documented by the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP), “The Nation’s Report Card.” The trend line is a gentle downward slope.13 This decline in reading ability necessarily entails a decline in general knowledge, because by the twelfth grade, general knowledge is the main factor determining a student’s level of reading comprehension.

This correlation between background knowledge and language comprehension is the technical point from which nearly all of my work in educational reform started. To understand a piece of writing (including that on the Internet and in job-retraining manuals), you already have to know something about its subject matter. The implications of that insight from my research on language shook me out of my comfortable life as a conference-going literary theorist and into the culture wars. My research had led me to understand that reading and writing require unspoken background knowledge, silently assumed. I realized that if we want students to read and write well, we cannot take a laissez-faire attitude to the content of early schooling. In order to make competent readers and writers who possess the knowledge needed for communication, we ...