![]()

CHAPTER ONE

Twilight of the Gods

I have described the triumph of barbarism and religion.

Edward Gibbon, 1776

The crumbling monuments of Constantinople were not the only traces that remained in the 1540s, a century after the downfall of Byzantium. Throughout western Europe, the libraries of kings, dukes and cardinals were filled with manuscripts of religious and classical texts in Greek that had once been carefully copied by Byzantine scribes. With the empire gone, the Turks had little use for its surviving books and happily sold them to envoys like Pierre Gilles who carried them back to their homelands. Others were brought out by refugees. These codices contained everything from the Gospels and the Psalms to the precious writings of the ancient Greek philosophers which for centuries had been unavailable in the west.

One of these manuscripts is Graecus 156, which is still preserved in the Vatican Library in Rome. There are hundreds of Byzantine manuscripts in the Vatican but this one is different. Its new clerical owners did not want it to be read and, until the middle of the nineteenth century, access to it was severely restricted. At some point in the past, several pages were carefully and deliberately cut out and their content is now lost forever. As a voice of subversion and opposition, it is amazing that it survived at all. Dating from the tenth century, Graecus 156 is a later copy of a historical account written in Greek about five hundred years after the birth of Christ. Its author was Zosimus, an obscure official about whom almost nothing is known, but who was a vital witness to the transition of the Roman empire to its successor state, Byzantium.

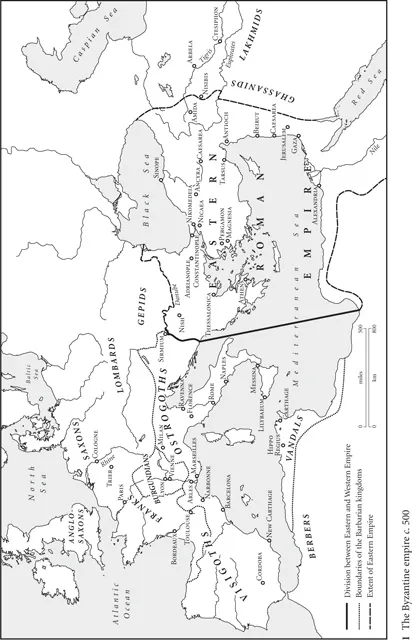

Zosimus was a witness from the losing side. He recounted the history of the empire up to the year 410 but made it clear from the outset that the story he was telling was one of decline and disintegration and that the empire of his day was not what it used to be. By the time he was writing, half of the empire’s territory had been lost. The western provinces had ceased to be under the rule of the emperor and had been parcelled out among various Germanic tribes whom Zosimus – in common with his fellow citizens – contemptuously labelled ‘barbarians’. North Africa was ruled by the Vandals, Spain by the Visigoths, Gaul by the Franks and Burgundians, Britain by the Angles, Saxons and Jutes. Even Italy and the empire’s old capital city of Rome were lost and now belonged to the king of the Ostrogoths. Instead, the eastern city of Constantinople had become the capital of what was left of the empire: the Balkans, Asia Minor, Syria, Palestine and Egypt. How had it come to this? Zosimus had no doubts on that issue. When a state becomes displeasing to the gods, he declared, its affairs will inevitably decline, for the empire had abandoned the Olympian deities who had brought it prosperity and victory in the days of its greatness and turned to the new-fangled religion of Christianity.

Nor did Zosimus hesitate about who was to blame for this impious abandonment of traditional worship and for the consequent decline of the empire: his history points the finger directly at the man who had been emperor between 306 and 337 as ‘the origin and beginning of the present destruction of the empire’. His name was Constantine and he was an upstart. True, his father Constantius had been an emperor but, as Zosimus acerbically recorded, Constantine himself was illegitimate, the product of a one-night stand with an innkeeper’s daughter. Somehow the boy had been able to get to the palace and worm his way into his father’s affections ahead of Constantius’ legitimate sons. In those days, the Roman empire still stretched from Syria in the south-east to Britain in the north-west, and when Constantius had marched off to secure the empire’s northern frontier, the ambitious Constantine had followed him. Constantius got as far as York but there he died in 306. The soldiers of his army promptly proclaimed young Constantine – the son of a harlot, as Zosimus calls him – as the next emperor. That was all very well but there were plenty of other men in the empire who aspired to supreme power and before long Constantine was at war with one rival after another. In 312 he defeated Maxentius, at the Milvian Bridge on the river Tiber, and became master of Rome and of the western provinces. In 324 he disposed of his former ally, Licinius, and so finally, Zosimus regretfully recorded, the whole empire was in the hands of Constantine alone.

Zosimus goes on to recount how Constantine, now in his fifties and the most powerful man in the world, no longer needed to conceal his ‘natural malignity’. That aspect of his character emerged, claims Zosimus, when he developed a suspicion that his young wife Fausta was having an affair with his son by an earlier marriage, Crispus. The young man was immediately executed. But Constantine devised a worse fate for Fausta: he had a bath house heated to excess and then had his wife locked in it until she eventually suffocated. When the deeds were done, Zosimus continued, Constantine suddenly began to feel pangs of guilt. Killing rivals in battle was one thing, terminating his own wife and son quite another. Perhaps he feared the gods might visit some terrible retribution on him, as they had done on the mythical Tantalus who murdered his son Pelops: that unnatural father had been sentenced to spend eternity standing up to his neck in water, suffering from a raging thirst, tormented by the cool water that receded just out of reach whenever he bent to drink. Eager to avoid such a fate, Constantine consulted priests and sages, but they all gave him the same unwelcome verdict, that the stain of so dreadful a crime could never be expunged.

At this point it happened that an Egyptian Christian turned up in Rome. By the early fourth century, Christians represented a substantial minority of the empire’s population and the Church had a strong following in some of the larger cities. Emperor Diocletian (284–305) had taken a very dim view of this growing religious cult and in 303 had issued an edict ordering that churches be demolished and copies of the scriptures be destroyed. Christians who held high office in the state were to be demoted and they were ordered to make sacrifices to the gods, on pain of death. The decree was implemented, albeit sporadically, and a considerable number of Christians died for their beliefs, but the Church as a whole was not destroyed and there were even a few Christians at the imperial court. Acquaintance with some of these got the Egyptian visitor admitted to Constantine’s presence and he assured the emperor that the God of the Christians would pardon even the most heinous of deeds. According to Zosimus, Constantine took the bait. He reversed the policy of Diocletian, put an end to the persecutions, began openly to favour the Christian Church and neglected the worship of the Olympian gods. Zosimus was horrified by this impiety and by Constantine’s abandonment of the religion of his forefathers.

That was not all: Zosimus levelled a second charge against Constantine, that he was responsible for building a new and completely unnecessary city that drained the population and resources of the empire. According to Zosimus, the emperor’s religious conversion had not made him popular with the people of Rome, especially when he attempted to prevent the traditional pagan ceremonies taking place on the Capitoline Hill, so he decided to move east and transfer his residence there. At first he opted to build a new city near the site of ancient Troy on the Dardanelles strait in Asia Minor, but after a few years he changed his mind and moved on. Finally he decided to opt for the city of Byzantion. To make it worthy of his presence, he decided that he would completely rebuild it, providing it with replicas of all the grand buildings and monuments that were to be found in Rome: a senate house; a central forum, known as the Augousteion; a stadium for chariot racing, the Hippodrome; and a grand imperial residence, the Great Palace. There were to be many churches and a great cathedral dedicated to the Holy Wisdom of God, or Hagia Sophia, but Constantine hedged his bets and made sure there were a few pagan temples too. The new metropolis was renamed in his own honour as Constantinople or ‘city of Constantine’. Zosimus deeply disapproved of the whole project and resented the huge sums, extorted by taxing other parts of the empire, that had funded it. Constantinople acted, he said, like a magnet for settlers from all parts of the empire, eager to cash in on imperial patronage. The population had soared and the streets had become dangerously crowded. Land for building had grown so scarce that suburbs had sprung up beyond the city walls and piles had been driven into the sea to support platforms on which still more houses could be built. The city was, in Zosimus’s eyes, a swelling ulcer that would one day burst and pour forth blood, a monument only to Constantine’s vanity and wasteful extravagance.

There was a third accusation that Zosimus added to those of impiously abandoning the worship of the traditional gods and of founding a completely unnecessary city. Effective though Constantine was in eliminating his internal rivals, he was less successful in dealing with the barbarians that were massed on the empire’s borders. When confronted by some five hundred barbarian horsemen who had invaded Roman territory, Zosimus claims, Constantine simply ran away. Moreover, while the pious, pagan emperor Diocletian had seen to it that the frontier had always been well defended by stationing soldiers in fortifications along its length, Constantine decided to quarter the troops in cities. Not only did this leave the frontiers undefended, it undermined the military ethos of the empire, allowing the troops to become lazy and self-indulgent. The Christian religion furthered the process, in Zosimus’s view, undermining the manly virtues that had made Rome great by promoting chastity and renunciation of the world as the new ideals. Monks, particularly, appalled him because they were ‘useless for war and other service to the state’. In the palaces of the emperors, eunuchs rather than soldiers came to dominate the corridors of power. Thus, even though it was not until about a hundred years after Constantine that the frontiers finally broke down, Zosimus emphatically blamed him for the decline of the empire and for the loss of the western provinces. ‘When our souls are fertile we prosper,’ he concluded, ‘but when sterility of soul is uppermost we are reduced to our present condition.’

* * *

Zosimus’s highly jaundiced views on Constantine and the decline of the empire were not shared by everyone. It was hardly surprising that Christians took a very different line on the man who had saved their Church from persecution and set it on the path to become the empire’s official religion. One of the first to voice his gratitude was the bishop of the town of Caesarea in Palestine, a certain Eusebius. A contemporary of Constantine, he had experienced the horrors of Diocletian’s persecution at first hand and, once it was over, he hastened to sing the praises of the new regime in a flattering biography of Constantine. The circumstances of the emperor’s birth were carefully avoided and the account opens with the young Constantine residing in the imperial palace. Already, Eusebius claimed, a virtuous spirit was drawing him towards a morality superior to that of the pagans around him. Indeed, his virtue and good looks inspired envy in the palace, so that he was forced to flee and head for Britain to join his father. So it was that God arranged it that Constantine should be on hand when his father died, and naturally he was chosen to succeed him. When it came to vindicating his grip on power against his enemies, God took care of that too. While encamped outside Rome in 312 preparing to do battle with his rival Maxentius, Constantine allegedly had a vision of a cross-shaped device superimposed on the sun with the words ‘Conquer in this’. That night, Eusebius wrote, Jesus Christ himself appeared to Constantine and commanded that he should make a replica of the device that he had seen in the sky and place it, as his standard, at the forefront of his army in the battle to come. It was this that led Constantine to victory at the battle of the Milvian Bridge and prompted him from then on to favour the Christian Church and to issue an edict putting an end to the persecution. Eusebius makes no mention of the murders of Crispus and Fausta, nor of Constantine’s guilt at their murder driving him into the arms of the Church.

For Eusebius, Constantine’s achievement of sole rule of the empire in 324 gave him full scope to develop his generous and pious nature. His refounding of Byzantion as Constantinople was not a waste of money and resources but an act of Christian devotion. The new city was designed to be a purely Christian one, unpolluted by pagan worship: the temples that Zosimus mentions have no place in Eusebius’s account. Nor, maintained the good bishop, did Constantine neglect the frontiers and give entry to the barbarians. On the contrary, he subjected them to Roman rule and, rather than Romans paying annual tribute money to barbarians, it was now the latter who came humbly to lay their gifts at Constantine’s feet. Far from being the ruin of the empire, Constantine was its saviour.

Clearly Constantine was one of those leaders who evoked either fervent devotion or bitter hatred in their subjects. From a more detached viewpoint it is possible to see Constantine’s reign as neither an unmitigated disaster nor the inauguration of a golden age, but rather as a process of transformation as the empire adjusted to the new and dangerous world around it. It is in Constantine’s time that all the characteristic elements of Byzantine civilisation can first be discerned: a monumental and impregnable capital in Constantinople; dominant Christianity; a political theory that exalted the office of emperor but also placed restraints upon it; an admiration of ascetic spirituality; an emphasis on visual expression of the spiritual; and an approach to the threat on the borders that went beyond the purely military.

* * *

In some ways, Zosimus was right to complain about the new and rapidly growing city of Constantinople. By about 500, the place was desperately overcrowded, and as a result it was dangerous and volatile. It only needed some tiny pretext for a riot to erupt in the streets. In the early years of the fifth century, the city’s archbishop or patriarch, John Chrysostom, was immensely popular and his fiery sermons always attracted a large congregation. Unfortunately he was not liked by Empress Eudoxia, the consort of Arcadius (395–408). Chrysostom had criticised her when she had helped herself to some property in Constantinople without taking much notice of the rights of the owners and she was deeply offended by some of his sermons which, while mentioning no names, denounced powerful, scheming women. In June 404 Chrysostom was sent into exile but his supporters took their revenge. Determined that no one was to be consecrated patriarch in Chrysostom’s place, a large crowd of his supporters broke into the cathedral of Hagia Sophia and set fire to it. By morning it was a smoking ruin.

It was not only religious issues that raised passions in early Byzantine Constantinople. The chariot races that were held in the Hippodrome attracted huge crowds of supporters for the two main teams, the Greens and the Blues. Successful charioteers enjoyed wide celebrity: poems were composed in their honour and their statues were as prominent in public places as those of the emperor. It was not unusual for fights to break out between rival supporters but what really terrified the imperial authorities was when the Blues and the Greens joined forces. In 498, several Green supporters were arrested for throwing stones. A crowd of their fellows gathered to demand their release from the emperor, the elderly Anastasius (491–518), but they received a blank refusal and a troop of soldiers was sent to disperse them. That was the signal for a general riot in the Hippodrome when the place was full to capacity for the races. The crowd started to throw stones at the imperial box, where the emperor had just taken his seat to preside over the event. One large rock, hurled by a black man in the crowd, narrowly missed Anastasius and the emperor’s bodyguards made a rush on the perpetrator and cut him to pieces with their swords. By now the exits to the Hippodrome had been sealed, so the crowd resorted to arson, setting fire to the main gate so that considerable damage was done to the stadium and the area round about. Eventually order was restored, after a few prominent malefactors had been singled out and punished, but it was another lesson in how quickly the crowded city could transform itself into a war zone.

While Zosimus might have been right about Constantinople’s volatility, in other respects he failed to appreciate the value of the new city. It had not come into being, as he claimed, simply because of Constantine’s need to escape from Rome and his own colossal vanity. There were very good reasons for creating a new city at that time and in that place. For some years, the emperors had ceased to base themselves permanently in Rome – the old capital was just too far from the threatened frontiers and some forward base needed to be found. In the western half of the empire, Milan and Trier were often used, while in the east, Antioch and Nikomedeia served the purpose. Constantine was seeking to create his own alternative base but he wanted somewhere worthy of permanent imperial presence, which was why, once he had decided on Byzantion as the site, he worked so hard to adorn the place with fine buildings reminiscent of Rome. Constantine also had strategic considerations in mind, for the site had not been randomly chosen, whatever Zosimus might say about his initially favouring the site of Troy. Constantinople was in a perfect position on the Bosporus, halfway between the Danube and Mesopotamian frontiers, a much more practical site than Rome, given the pressure on the borders. Moreover, as even Zosimus had to admit, it provided a secure refuge, for it was situated on a narrow and easily defended promontory between the sea and one of the finest natural harbours in the world, the Golden Horn. Constantine made the site even stronger by sealing it with a defensive wall on the landward side. In the following century, a new set of fortifications – the Theodosian Walls, or Land Walls – were constructed, enclosing a larger tract of land within the city. Constructed of limestone blocks five and a half metres thick, they effectively made Constantinople impregnable by land. A single span of wall was built along the seaward sides of the promontory too, effectively protecting it from attack by a hostile fleet. If the site did have a weakness, it was the lack of a fresh water supply, but that was remedied by the construction of aqueducts to bring in the water and underground cisterns to store it. What Zosimus was never to know was that, when times became hard and the empire was beset on all sides, Constantinople was to become one of its greatest assets, surviving siege and blockade time after time. Even the pretentious buildings and wide-open squares were to prove their worth, making Constantinople a showcase capital, impressing visitors with the empire’s wealth and power and bolstering its claim to be the centre of the Christian world.

* * *

Significant though the foundation of Constantinople was, the pervasiveness of the Christian religion is undoubtedly the element that most sharply distinguishes the Byzantine empire from the Roman world that preceded it. In Roman times a plethora of local deities and cults had existed alongside the official worship of the Olympian gods. In Byzantium there was only one religion, and only by accepting it could you be a loyal subject of the emperor. Whatever Eusebius and other Christian writers tried to suggest, this change did not happen overnight. Constantine’s personal conversion did not immediately lead to that of the whole empire but rather inaugurated a gradual Christianisation. After his victory at the Milvian Bridge in 312, Constantine rode into Rome in triumph and erected a monumental arch to celebrate his success, but nowhere on it were there any specific Christian references apart from a vague statement that the victory was won ‘at the prompting of the deity’. In 313, he issued an edict of toleration which brought the persecution of Christians to an end. Later in his reign he made Sunday a public holiday, entered into friendly correspondence with Christian bishops and began to subsidise the Christian Church with public funds. On the other hand, the emperor made no serious attempt to outlaw the worship of the old gods, and their temples and sanctuaries continued to operate much as before. Even after Constantine’s death in 337, there was no concerted attempt to force Christianity on all the people of the empire. His son, Constantius II (337–3...