![]()

CHAPTER 1

Welcome to Rainbowland

(JULY 2009)

SPLAYED ON A raggedy mattress in the back of a pickup truck I fake-smile, petrified. We’re en route to Rainbowland, a festival I’ve never been to before, in a vehicle without seatbelts. A kid we just met a couple minutes ago, Sticky, is munching on garlic cloves beside me; he’s tossing them into his beak like they’re bubblegum. Sticky beams triumphantly. He’s not the least bit self-conscious of his ripe bare feet or omnipresent body odor. He shouts blissfully out the window to no one in particular, long hair flowing biblically in the wind. “Lovin’ you!” he says. “Lovin’ you!”

I’m not sure where Kitra found this man, but he’s hooked us up with a ride into Rainbowland. I trust Kitra without question. We’re in New Mexico on assignment for an Italian magazine called COLORS: Kitra to take photos and me to write text and help carry gear. I’ve never been to a Rainbow Gathering before. Kitra has been to one in Israel. My bladder pinches, but I keep my mouth shut. I know I’m green—fresh meat.

“Coffee break!” shouts Amanda, the woman behind the wheel. “Everybody out!”

Amanda is a first-timer, too. She smiles defiantly. Her shirt reads: International Indigenous Women’s Day.

We pick up more people along the way: Braham, a Robert Plant look-alike with a pill-white cast on his leg, and Jesse, a man in his twenties with a shaved head and expensive ball cap. When we pick up Jesse, Sticky jumps on him with a hug and yells, “Brother!” They’re family from Rainbows past and are excited to have met up so serendipitously.

On the highway, Jesse sits too close to me on the communal mattress, adjusting his cap. He tells me about his work as a volunteer firefighter, how he hops from helicopters to extinguish roaring bush fires. My head jangles back and forth in the backseat. I keep my eyes on the horizon to avoid feeling nauseous.

“What’re your chances of getting hurt?” I ask.

He says he doesn’t know. I change the topic to Rainbowland, which is why I’m here. Jesse becomes very sentimental almost immediately. He tells me how he first got involved with the Family—the close network of Rainbow attendees.

“At fourteen I was on the streets. I could have gone down some really bad paths,” he tells me. “But Rainbow set me straight. Actually, Rainbow saved my fucking life.”

Soon, Jesse is inviting me to move into his yurt in Northern California, to live with him, off the land on his off-the-grid property. “I came to this Gathering to find a Sagittarius girl like you,” he tells me. “Libra and Sagittarius are the perfect match, you know.”

“Kitra’s a Libra,” I reply awkwardly, kicking the communal mattress. Kitra looks up from her camera screen, oblivious. She smiles, luminescent: long-limbed and starry-eyed, she snaps photos of the wacky foliage unfolding through our cracked windowpanes.

Two months earlier, I’d graduated from McGill University in Montreal, where I’d majored in anthropology and world religions. While there, I devoured ethnographies detailing the cultural customs of the African Nuer, the cheese-making techniques of the Persian Basseri, and the cultural customs of the Nuer of Sudan and the Sarakatsani of Greece. But it wasn’t enough for me. I wanted to understand the nomadic cultures of my own continent, from my own perspective.

I’d met Kitra at McGill in an experimental religion class. Our professor, who insisted we refer to him by the moniker Lumière, was a tall, balding man with an ineffable spirit. In a stuffy school hell-bent on pomp and circumstance, he played the Pink Floyd song “Another Brick in the Wall” full blast at the beginning of each and every one of our lectures. He forced us up onto our feet to march in unison with our classmates, encouraging us to sing along with the lyrics, which he provided to us on paper.

Kitra, wearing an oversized shirt and dark glasses, sat in front of me on our first day. I told her I liked her top because I wanted to talk to her. She thanked me in her soft, solemn voice, saying she thought it might be her sister’s.

“We don’t really have our own clothes,” she told me. “We just have a pile we all share.”

This idea was so foreign to me. My WASP upbringing demanded we all have our own belongings, our own deep closets.

Lumière insisted each of us go by our own monikers. Kitra chose the name Dogmeta 95, in homage to director Lars von Trier’s film movement, and I called myself Lady X, which I think was a vague reference to Sylvia Plath’s “Lady Lazarus” mashed up with Bowie’s “Lady Stardust.” We really didn’t think them through. At the end of class, Lumière told us we would go by those names, and those names only, until the end of the semester. So, we did.

In Lumière’s class, I learned about Kitra’s photography and career as an artist. She told me about her experiences as a teenager: photographing the Gaza Strip and landing her photo on the front cover of the New York Times, working as an assistant for a celebrity photographer in New York City. I was in immediate awe of her. To my delight, we quickly became inseparable. We started collaborating on stories to pass the time, traveling to London, Ontario, to cover an LGBTQ2 prom and to Coney Island to interview carnival workers. This collaboration would eventually lead us to Rainbowland.

The university fired Lumière a year later, which was a real shame, as his class was the most valuable one I took at McGill.

AS WE APPROACH the Santa Fe National Forest in northern New Mexico, the road turns to gravel soup. Cars line the roadsides like stubble: Volkswagen vans, Hondas, BMWs, and multitudes of multicolored school buses. Plates hail from Minnesota, South Dakota, New York, Nebraska, and beyond. Bumper stickers scream: QUESTION REALITY, ARMS ARE FOR HUGGING, VIETNAM VET ON BOARD, and PEACE: BACK BY POPULAR DEMAND. A few cars lie upside down in the ditch, having toppled over after being parked on shifting ground.

Amanda drives, slower now. From the window, I spy shoeless children, tattooed men sitting shirtless in lawn chairs.

“Welcome home!” Sticky shouts, still beaming.

“Lovin’ you!” a man yells back from the road.

I’m overwhelmed by the call and response, by the oddities surrounding our vehicle—the clanking wheelbarrows, dilapidated buses—by the huge smiles everywhere I look. A young woman rides past our truck, bareback on a white stallion. She’s carrying a newborn baby in a hand-sewn sling across her chest. I’m utterly awestruck, unable to speak. Kitra sits calmly, dreamily, waiting for the vehicle to come to a stop before exiting.

“It’s a couple miles’ hike to the site,” Jesse says. “We’ll carry those bags for you.”

I spy a hand-cut path leading down a bank into wilderness. Sticky and Jesse grab our gear and tell us they’ll come back for their own later.

THE FIRST OFFICIAL Gathering of the Rainbow Family of Living Light was held in 1972. The event, which took place in the Arapaho National Forest, Colorado, brought together more than twenty thousand Americans to live communally in the woods for more than a week. Their mission: to pray for world peace on the Fourth of July. Times have changed, but Rainbows, as the attendees are called, haven’t stopped gathering since, in an unbroken chain of Gatherings, year after year. They build, operate, and then deconstruct a fully functioning temporary society in the middle of a national forest every summer.

Original Rainbow attendees were from a mishmash of subcultures: mainly hippies hell-bent on communal living, tripping flower children trailing off the ’67 Summer of Love, Vietnam War protestors, Hells Angels bikers, and swaths of high school dropouts. Today, participants include homeless folks, crusty punks, and inner-city youth who come for the sense of community, free food, and stability the festival offers. Many homeless Rainbows make a life of jumping from Gathering to Gathering all year long. Gatherings have maintained popularity, with many events hosting more than thirty thousand participants. Regional Rainbows and international events occur throughout the year across the globe. Hippies are still the bread and butter of Rainbow culture, but because of its open, inclusive nature, Rainbowland is also a haven for people who just don’t fit into the mainstream—poor Americans, those who have nothing to their name, full-time travelers, and teenage runaways. We’re here to interview members of these last two groups.

THE ONLY PUBLISHED ethnography about Rainbowland is entitled People of the Rainbow: A Nomadic Utopia by Michael Niman. In it, Niman attempts to explain the Family’s population: “Some members live under bridges, some in condominiums. For most, the Gatherings are a vacation from Babylon, but for a dedicated minority, Rainbow is a way of life.” Babylon, I will soon learn, is the term for society outside of Rainbowland. It’s a catchall, not a specific place on the map. Babylon is what traveling kids call any town, city, or space outside of Rainbowland, any place that’s not “home.”

In All Ways Free, the unofficial Rainbow Family newspaper, the Gathering is described as a “diverse and decentralized social fabric woven from the thread of hippie culture, back-to-land-ers, American Indian spiritual teachings, pacifist-anarchist traditions, eastern mysticism, and the legacy of the depression-era hobo street wisdom.”

Not everyone sees Rainbow in a positive light. The Department of Homeland Security has named the Rainbow Family an official “terrorist threat,” a threat to national security. Local and national police forces and park rangers spend thousands of dollars annually to monitor Gatherings—often much more money than it takes to run the actual event. Since 1972, United States government agencies have demanded to negotiate with leaders or spokespeople, but Rainbow only offers “liaisons” to aid in conflict resolution. Legally, nobody is allowed to speak for the Family—spokespeople, leaders, and presidents are not part of this model. This means the police are unable to charge this decentralized group of thousands of people for the organization of the event, though local townships regularly attempt to take legal action, and police presence at Gatherings is almost guaranteed. Despite this, Rainbows insistently continue exercising their right to assemble on public land, to pray for peace on the Fourth of July.

THE ROAD TO the main site is rough and bumpy. Handwritten signs hang limply from trees: WE LOVE YOU, DOSE ME, FUCK UNCLE SAM, WELCOME HOME! We pass bright eyes everywhere. I’m told the site was set up by Seed Camp—a group of the more hardcore Rainbows who come early to scout, clear, and maintain the site, and who stay late to return the land to its original form, ensuring the park environment is not compromised. Those involved in Seed Camp are often regular Rainbow attendees who spend weeks or months in the woods.

After half an hour’s hike we reach Main Meadow, the center, or town square, of Rainbowland. Main Meadow is where the annual Prayer for Peace is held—the central event of this Gathering, a tradition carried on from the very first Gathering. This is where thousands will gather and pray on the Fourth. I look out at the large plain of burnt grass, almost as big as a football field, which holds hundreds of humans sitting in shapes, strumming instruments, reading books and manifestos, writing poetry, hula-hooping, and practicing devil sticks. There is an ever-present unyielding and ominous drum heartbeat. Hand-forged paths cover the periphery of the meadow, trails to hundreds of Rainbow kitchens, hidden in the woods. Some Rainbows have been on the site for weeks already, and the excitement is only ramping up as more people arrive.

“Hell yeah,” Jesse shouts. “Welcome home!”

A hand-built information booth—a tiny, creaky hut—sits at one side of Main Meadow, where Main Circle, the Prayer for Peace on the Fourth, is held. Inside are handwritten maps of this year’s setup, ride-share boards, schedules for free skill-share workshops, and a big box of clothes with a sign reading FREE.

“Where’s Shtetl Kettle this year?” Sticky asks a man attending the booth.

Sticky’s looking for a kosher kitchen that he’s camped at before; the same kitchens appear year after year at Gatherings.

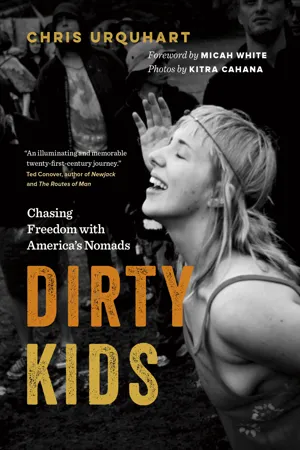

Young travelers congregate at Dirty Kids Camp, one of the darker dwellings in Rainbowland, to share smokes, rats, and guitar riffs.

NEW MEXICO, JULY 2009

He’s told they aren’t here this year, but the man suggests he try Turtle Soup instead. Swapping camps is a common occurrence; kitchens change, evolve, and swallow one another whole. Jesus Camp, Montana Mud, River Rats, Lovin’ Ovens, Death Camp, Fat Kids Kitchen, and Shut Up and Eat It: Rainbow kitchens of various names feed thousands of Family members a day, all for free. In fact, everything in Rainbowland is free. Supplies are donated, forged, or “liberated” from the local town dumpsters (often to the dismay or, at times, sheer delight of the surrounding townships). There are long-standing camps that are generally in attendance at annual Gatherings, but Rainbows always adapt, moving, shifting. Kitra and I are on the search for a kosher vegetarian kitchen as well, so we follow Sticky.

“Seven up!” I hear a voice call through the forest.

Then I spy a congregation of police officers and park rangers on horseback passing through. The call amplifies as soon as it...