- 428 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Black Democracy - The Story of Haiti

About this book

Many of the earliest books, particularly those dating back to the 1900s and before, are now extremely scarce and increasingly expensive. We are republishing these classic works in affordable, high quality, modern editions, using the original text and artwork.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Black Democracy - The Story of Haiti by H. P. Davis in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & World History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

INTRODUCTION

WHEN the average American hears of Haiti, if he does not confuse it with the island of Tahiti—thousands of miles away in the Pacific—he thinks of a small, unimportant West Indian country productive of revolutions, surcharged postage stamps, and newspaper discussions of the American intervention or perhaps of alleged atrocities by the United States Marines. Of the difficult and complicated problems involved in the task which the United States has assumed in Haiti, or of the steps so far taken towards its accomplishment, reports published in the United States have been so conflicting as to bewilder the average reader. Of the Haitians themselves, their background, or present condition, the American people generally have no conception.

Frederick Douglass, the great Negro orator, once said something to the effect that in measuring the progress of a race or people one must consider not only the heights to which the race has attained, but the depths from which it sprang. To reach any understanding of conditions in Haiti to-day, it is necessary to realize something of the fascinating and tragic history of the island now divided between the black republic and the mulatto (Dominican) republic.

No country in the world, civilized or uncivilized, has had within the same space of time a more dramatic or more distressing history.

When Columbus landed on the island which he named Hispaniola, he was welcomed by a primitive people estimated to number a million souls. Fifteen years later this people had been reduced by cruel exploitation to 60,000. Scarcity of labour resulting from their swift extermination led to the importation of Negroes from Africa, and thus was initiated the slave trade which was profoundly to affect the political and economic future of the Americas. The Spanish adventurers were essentially seekers for gold, and the natural resources of Hispaniola remained practically neglected until the settlement by the French in the eastern part of the island in the middle of the fifteenth century.

Though the French developed, in the eastern part of this island, the richest colony in the world, they, like the Spanish, lost their potentially most valuable colonial possession through disregard of the first principles of humanity and expediency. Just complaints of the French colonists against the home government (which was infinitely more tyrannical than that of England over her American colonies) were finally aggravated to the breaking point by the Jacobin colonial policy of the Estates-General, which threatened to deprive them of their chief possessions, the slaves. Dissension between the colonists and the home government, then in the throes of the French Revolution, was seized upon by the mulatto caste as affording an opportunity to better their condition, but armed attempts to obtain recognition of their rights were unsuccessful. Finally the great mass of the blacks, realizing their strength, rose against their masters. They ravaged the island with fire and sword, drove out the whites, and finally Dessalines, “the Tiger,” standing on the beach at Gonaives, tore the tricolour of France into three pieces. Dramatically hurling the white portion into the sea, he united the red and blue and created the flag of independent Haiti.

The history of the Haitian struggle for independence is as dramatic as that of any nation in the world. The three great black leaders, Toussaint l’Ouverture, Jean Jacques Dessalines, and Henri Christophe, had all served the whites in various capacities, from that of slaves to general officers in the Army of France in St.-Domingue. The mulatto Pétion, first president of the Republic of Haiti, was a graduate of a French military school. The influence of the despotic government under which they had lived and the French ideals inherited from their former masters may be traced in the careers and policies of the early leaders and of all the subsequent rulers of independent Haiti. Even today the French influence predominates. The official language is French, as is also the culture of the small class which constitutes the élite of Haiti.

The history of the Spanish part of this island, of the French colonial period, and of the Haitian struggle for independence has been written in Spanish, French, German, and English. A great number of books, pamphlets, and articles have been published on the Haitian Republic and on the American intervention. Nothing, however, is available to the general reader which might enable him to trace the history of the Haitian people from the discovery of Hispaniola by Columbus to the present time.

After a long residence in the black republic and a careful study of its history, including material not ordinarily available, the author ventures to present this story of Haiti. A study of the available historical material discloses such marked discrepancies, and such conflicting opinions as to the more prominent figures in the struggle for freedom and the early history of the Haitians as a free people, that accurate analysis of the principal characters and events of this most amazing drama is now impossible.

In treating of this period, the writer has attempted only to review the more important aspects of the careers of the individuals who freed the country from France and created the black republic. To others more ably equipped is left the fascinating task of dramatizing this extraordinary story. For readers who may wish additional detailed information, an appendix and brief bibliography have been added to this volume.

The story of Haiti may be roughly divided into six periods: the pre-Columbian or aboriginal period, the period of Spanish discovery and settlement, the period of French colonization and development, the period of internal strife ending in emancipation of the slaves, the inauguration and turbulent history of the black republic, and, finally, Haiti and the American intervention.

It is the story of the second-largest and one of the most fertile of the islands of the Caribbean Sea, the first land colonized by Europeans in the Western World, and for years the seat of Spanish rule in the Americas. The island was discovered by Columbus and visited by Pizarro, Ponce de Leon, Cortez, and Velasquez. It was attacked by Drake, and the blood of the buccaneers survives in the mulatto aristocracy. For many years it contributed vast sums to the wealth of the kingdom of France and was the source of over a third of French commerce. It is of extraordinary natural beauty, which might almost have inspired Rousseau’s dreams of the ideal primitive state of nature. We will borrow the words of Washington Irving to describe the land to which Columbus gave the name of Hispaniola:

“In the transparent atmosphere of the tropics, objects are descried at a great distance and the purity of the air and serenity of the deep blue sky give a magical effect to the scenery. Under these advantages the beautiful island of Haiti revealed itself to the eye as they approached. Its mountains were higher and more rocky than those of the other islands; but the rocks rose from among rich forests. The mountains swept down the luxurious plains and green savannahs; while the appearance of the cultivated fields, of numerous fires at night and columns of smoke by day, showed it to be populous. It rose before them in all the splendour of tropical vegetation, one of the most beautiful islands in the world and doomed to be one of the most unfortunate.”

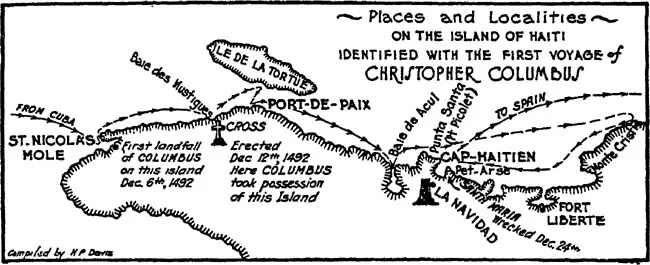

~~ Localities in Haiti Identified with the First Voyage of Columbus ~~

CHAPTER I

THE SPANIARDS

ON December 6, 1492, Columbus sighted the island of Haiti, and that evening entered the harbour of Mole St. Nicholas. Leaving the Mole on the following day and skirting the north coast, he landed at the Baie des Moustiques and, on the 12th of December, erected a cross at the entrance of this harbour and with great ceremony took possession in the name of his sovereigns of the island, to which he gave the name Hispaniola. Columbus, in a report to Ferdinand and Isabella, said of the aborigines: “So lovable, so tractable, so peaceable are these people that I swear to your Majesties there is not in the world a better nation nor a better land. They love their neighbours as themselves; and their discourse is ever sweet and gentle, and accompanied with a smile; and though it is true that they are naked, yet their manners are decorous and praiseworthy.” The fact that there exists to-day not one pure-blooded descendant of this race is eloquent testimony to the unfortunate subsequent history of these “so lovable and tractable” people.

While cruising along the coast, Columbus encountered a large canoe manned by Indians, who invited him to visit their cacique, Guacanaguari, who later was to play an important part in the relations between the Conquistadores and the natives of Hispaniola. It was while attempting to locate the village of this chief that Columbus was wrecked in his flagship, the Santa Maria. Cacique Guacanaguari came at once to the rescue, and by his aid the vessel was unloaded and the cargo and stores safely deposited on the shore. No civilized people could have observed more scrupulously the rights of ownership than did these savages. Merchandise of all descriptions, beads, hawks’ bells, looking-glasses, and showy trifles of all kinds were strewn on the beach, together with the more practical essentials brought by the Spaniards. Nothing was touched; the Indians in no way took advantage of the misfortunes of the white strangers.

The Pinta had become separated from the fleet before the landing at Mole St. Nicholas, and the loss of the Santa Maria left the Admiral with only the Niña, a small and far from seaworthy ship totally incapable of accommodating all the Spanish adventurers. In this predicament Columbus determined to return to Spain, report his discoveries, and fit out a new expedition to take possession of the New World. The natives, who lived in deadly fear of periodical incursions of wild bands of nomad Caribs, gladly assented to the proposal that a number of the Spanish mariners should be left to’protect them.

The kindly attitude of the Indians and the indolent and easy life which they had lived since the wreck of the Santa Maria so appealed to the Spaniards that Columbus had no difficulty in securing volunteers to remain on the island. From the wreck of the Santa Maria a tower named La Navidad was constructed, and fortified with the guns taken from the wreck. Having garrisoned this tower with thirty-eight men, Columbus sailed for Spain to report his discoveries.

It was a most romantic age, and nowhere in Europe was the adventurous spirit more prevalent than in Spain. The wars with the Moors being over, the grandees and soldiers of Spain, tired of peaceful monotony, were eager to accept any exploit which promised aggrandizement or gain. The visionary reports of Columbus and the extravagant accounts of his followers, whose vague recollections were by now but confused dreams, were accepted and exaggerated by the people until the most extraordinary fancies were entertained with respect to the New World. Hidalgos of high rank fresh from the romantic wars of Granada, and ecclesiastics eager to convert the heathen, joined with adventurers who were seeking only a chance to make their fortunes. Altogether it is probable that not less than fifteen hundred souls took passage with Columbus in the three large ships and fourteen caravels which sailed from the Bay of Cadiz, September 25, 1493.

Two months later this fleet arrived off the coast of Hispaniola and anchored in the harbour of Monte Cristi. Spanish sailors, ranging the coast, found on the green bank of a small stream the bodies of a man and a boy. The former had a cord of Spanish grass about his neck, and his arms were extended and tied to a stake in the form of a cross. Their bodies were so badly decayed that it was impossible to tell whether they were Indians or Europeans. But Columbus’s worst doubts were confirmed on the following day, when, at some distance, two other bodies were found, one of which, having a beard, was undoubtedly the corpse of a white man.

The natives had from the beginning been friendly to the Spaniards. They had allowed the garrison of La Navidad to choose wives from their number, and had gladly indicated to them the streams in which could be found the yellow metal they sought so eagerly. But the Spaniards had appropriated so many of their wives and daughters, and had conducted themselves with such brutal licence, that the natives had finally risen and, led by Caonabo, a chief of Carib birth, massacred the entire garrison.

When met by Columbus on his return from Spain, the natives showed every evidence of friendship, but the discovery of the massacre at La Navidad naturally led to distrust of the Indians and provoked the Spanish to reprisals which soon led to open hostilities, and finally to ruthless slaughter of the weaker people. On the return of the Admiral from a voyage of discovery in the south and west, he found the most deplorable conditions existing in the colony.

Bartholomew Columbus, who had been left in charge, had neither the strength of character nor the prestige necessary to control this band of restless adventurers, most of whom were soldiers of fortune fresh from the Moorish wars, and many of noble birth. The principal officers had not come to create a colony, but to seek gold and precious stones. The adventure they sought failed to materialize and they bitterly resented being subordinate to the Columbus brothers, to whom they considered themselves greatly superior. Expeditions into the interior resulted in the finding of some gold, and the plants and seeds brought from the mother country produced an abundant harvest. Columbus had, however, been unfortunate in the selection of a site for his capital; the unhealthy location of Isabella and the exposure to the heat and humidity, to which the Spaniards were unaccustomed, as well as the labour attending the building of the new town, resulted in sickness and discontent among the adventurers, who had anticipated a far different and less laborious life. Many openly disregarded the Admiral’s instructions in their treatment of the natives, and some of the influential grandees became disgusted with conditions and returned to Spain bearing evil reports of the new colony. Their departure deprived the colony of many of the most responsible leaders, and the licentious conduct of their fellows had destroyed all hope of friendly relations with the Indians.

In 1500 Bobadilla, who had been sent to investigate complaints against the administration of Hispaniola, arrived while Columbus was absent on another voyage of discovery. He assumed absolute command of the colony, and on the return of the Admiral arrested him and sent him in chains to Spain. Although the Spanish crown disavowed the action of Bobadilla and appointed Ovando in his place, Columbus was deprived of his authority and never regained either his title or the share of the revenues which had been promised him.

Ovando arrived in April, 1502, with considerable reinforcements and stores. He was a harsh but thoroughly competent soldier who had served with distinction against the Moors, and in spite of a record of atrocious cruelty his administration was marked by a period of prosperous development which, though it lasted only a short time, resulted in a decided growth in the importance and wealth of the colony.

Forty thousand natives of the Bahamas were imported by Governor-General Ovando on the shallow pretext that they would thus secure the benefits of the Christian religion, but in reality to replace the rapidly disappearing islanders. Notwithstanding this accession to their numbers, and strict injunctions from Spain that the natives should be treated with kindness, the Indian population was rapidly exterminated.

Sugar-cane, imported from the Canaries in 1506, was particularly adapted to the soil and climate and soon became an important product. Within a few years after its introduction, the cultivation of cane and extraction of sugar were the chief source of wealth of the colony.

Ovando was succeeded by Don Diego Columbus, son of the Admiral. The new Governor being accompanied by his wife, daughter of the famous Duke of Alva, and by a large number of distinguished and wealthy Spaniards, life in the colony assumed a far more brilliant aspect under his administration and the city of Santo Domingo, then the capital of the Spanish possessions in the New World, reached the height of its prosperity.

But the rapidly increasing expenses of the colony and the insatiable demands of the home gov...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Contents

- Illustrations

- Exhibits

- Part I

- Part II

- Notes

- Exhibits

- Bibliography

- Index