- 122 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

The author of

Vermont Firsts and Other Claims to Fame examines the pivotal American Revolutionary War skirmish and the men behind it.

In April 1775, a small band of men set out from Hartford and traveled swiftly north toward the shore of Lake Champlain, recruiting men to their expedition along the way. Within only a few days, this loyal group of volunteers arrived in Vermont and, joining forces with Ethan Allen and his legendary Green Mountain Boys, launched a daring attack to capture more than one hundred cannons stored at Fort Ticonderoga.

In this comprehensive look at "America's First Victory," Richard Smith traces the Patriots' route from Connecticut, through the towns of western Massachusetts and the Berkshire hills and north to Bennington, Vermont, and Lake Champlain. He chronicles the rival expedition led by Benedict Arnold, his confrontation with Allen, and the surprise attack that changed the course of the American Revolution.

In April 1775, a small band of men set out from Hartford and traveled swiftly north toward the shore of Lake Champlain, recruiting men to their expedition along the way. Within only a few days, this loyal group of volunteers arrived in Vermont and, joining forces with Ethan Allen and his legendary Green Mountain Boys, launched a daring attack to capture more than one hundred cannons stored at Fort Ticonderoga.

In this comprehensive look at "America's First Victory," Richard Smith traces the Patriots' route from Connecticut, through the towns of western Massachusetts and the Berkshire hills and north to Bennington, Vermont, and Lake Champlain. He chronicles the rival expedition led by Benedict Arnold, his confrontation with Allen, and the surprise attack that changed the course of the American Revolution.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Ethan Allen & the Capture of Fort Ticonderoga by Richard B. Smith in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Early American History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I

The Seeds and Forces of

Rebellion Are Created

THINKING THE IMPOSSIBLE: CAPTURING FORT TICONDEROGA

The massive Fort Ticonderoga, which would become known as the “Gibraltar of the Americas,” sits on a point high above Lake Champlain with over one hundred cannons and a star-shaped design that allows gunners to fire at any attacker from many directions. In 1758, 3,500 French defenders of Fort Ticonderoga held off about 16,000 attacking British soldiers.

Besides the physical size and design of the fort, colonial patriots in 1775 had to overcome many other obstacles, such as issues of command, lack of formal military training, lack of artillery or wall-scaling equipment and, in some cases, travel of more than two hundred miles—some from as far away as Connecticut. They had to recruit one by one in areas with small populations, get spies into the fort and keep the mission a secret yet march through land filled with many Tory (Loyalist) sympathizers. They had to obtain boats to cross Lake Champlain itself, worry about reinforcements from Canada and risk the possibility of losing their own land even if they won. How Fort Ticonderoga was captured by fewer than three hundred citizen soldiers and the story of the people who had become so oppressed to even attempt this can be found in the history of settlement of the early American colonists.

TENSIONS BETWEEN THE FRENCH AND ENGLISH MOUNT

The French and British Struggle Leads to an Uninhabited Wilderness

Ever since such early explorers as France’s Marquis de Champlain and England’s Henry Hudson in 1609, the British and the French had been major forces in trying to stake a claim of a part of the east coast of North America. The line between the French and British interests in the Northeast was disputed, and there were conflicts. The French and Indians in the north had even raided as far south as Deerfield, Massachusetts, in 1704.

With all of the tension and fear of French and Indian raids, the area known today as Vermont was an unoccupied wilderness located between the French and the English in the south (Massachusetts and Connecticut), as no settlers dared live there. The claim on the area by the English colony of New York was based on the 1664 charter from Charles II to the Duke of York that argued that the Connecticut River was the eastern border of New York. About 1741, New Hampshire became a royal colony of its own, and the king appointed Benning Wentworth as the royal governor. Also at this time, the Crown ruled that the border of New Hampshire and Massachusetts was farther south by a few miles than it was previously. This meant that Fort Dummer—which had been built west of the Connecticut River in today’s Brattleboro area in 1743 to protect Massachusetts from French and Indian raids—was no longer in Massachusetts. The Crown gave responsibility for Fort Dummer to New Hampshire and not New York. Based on his new responsibility for Fort Dummer and on many other vague justifications, Benning Wentworth claimed that he could grant land and charter towns all the way to a boundary twenty miles east of the Hudson River.

Hence, in 1749, Benning Wentworth chartered the first of many towns west of the Connecticut River and called it Bennington. Although the New York royal governor objected, Wentworth chartered fifteen more towns (all were about six by six miles in size) before stopping in 1755 when the French and Indian War was about to begin. Of course, these were “paper” towns because no settlers dared to go there because of French and Indian raids.

The French Build Fort Carillon (Fort Ticonderoga)

To counter the British building a fort at the southern end of Lake George, the French started construction in 1755 of a fort fifteen miles south of their own Fort St. Frederic at Crown Point on Lake Champlain. This new fort on Lake Champlain was initially called Fort Vaudreuil but was referred to later as Fort Carillon (later still to become Fort Ticonderoga). Construction of Fort Carillon took three years.

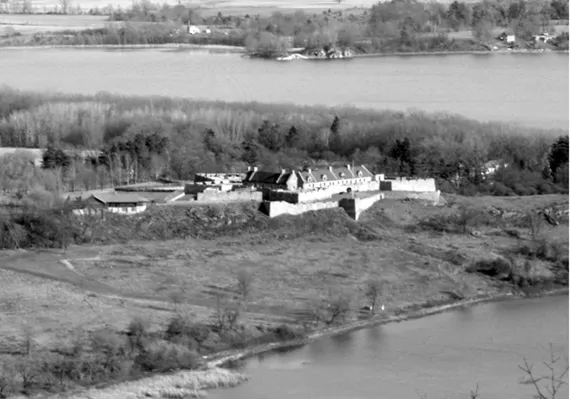

FORT TICONDEROGA, TICONDEROGA, NEW YORK. Today’s Fort Ticonderoga is shown with Vermont in the background and Lake Champlain looping around the peninsula. Photo by Nathan Farb. Courtesy Fort Ticonderoga.

The location of the new fort was chosen carefully. It was sited at a narrow point on Lake Champlain so that artillery from the fort could hit vessels trying to travel north or south on Lake Champlain, thereby guarding the natural trade route from Canada south to Albany and New York City. It also would guard the three-mile portage route between Lake George and Lake Champlain where the Lake George waters flow into Lake Champlain.

The fort itself is located on a cliff, which would make an assault from the south difficult. Fort Carillon was designed to protect against forces moving north (i.e. the English). The chief designer was Marquis di Lotbiniere, who built it in the four-bastion star style of Maréchal de Vauban. The star shape allowed for deadly crossfire shooting if any troops attempted to attack. Over the next twenty years, the fort would be in many states of repair. Originally a log construction, it was reinforced in many places with stone. The original four-sided fort had four star-shaped “bastions” added, and then two demilunes (walled triangle structures) were placed to the west and north and connected to the main fort by wooden bridges. These latter fortifications alone demonstrate the desire to thwart a ground attack that would most likely come directly into the fort from the north or the west but not from around the fort from the south. The southern wall between the fort and the lake was eventually stone. It was designed for a permanent garrison of four hundred men but was supplemented with some forces camping outside. It would have two to four thousand French troops during the summer.

Two years after the start of the French and Indian War, the British, to counter the southern movement and raids of the French, moved north in July 1758 under General Abercrombie to attack the French at Fort Carillon. In a massive, bloody battle on July 8, the British were defeated even though they had overwhelming forces (16,000 British to 3,500 French defenders).

The following year, 1759, the British under Jeffery Amherst attacked again, but the French merely evacuated Fort Carillon, blowing up the magazine and doing the same to the fort at Crown Point as they retreated to Canada. The British changed the name of Fort Carillon to Fort Ticonderoga.

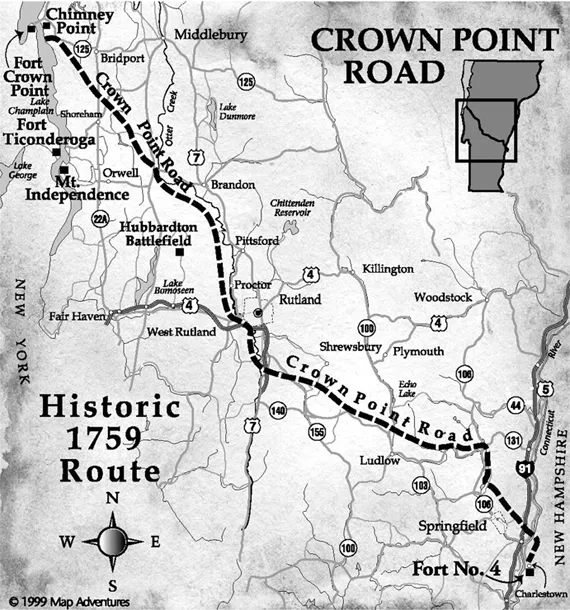

British Build a Road and the War Ends

While the French were retreating to Canada, repairs were made to Fort Ticonderoga, and Jeffery Amherst decided in 1759 to build a military road running from the Fort at Number 4 (modern day Charlestown in New Hampshire) to the narrows at Crown Point northwest diagonally across the current state of Vermont. This would allow for bringing men and matériel to the Champlain Valley from Boston and the Atlantic Ocean and help to pursue the British attack on the French in Canada. Although its route was changed in sections and had periods of improvement and disrepair, fifteen years later sections of this twenty-foot-wide road would be used by the colonial patriots in the recapture of Fort Ticonderoga.

The road supported the British, who on September 13, 1759, defeated the French at Quebec. Then, one year later on September 8, 1760, Montreal surrendered, thus ending the North American portion (the French and Indian War) of the Seven Years’ War. Although the final peace treaty, the Treaty of Paris, was not signed until 1763, it was clear that the French had been driven from North America when both Quebec and Montreal fell, in 1759 and 1760, respectively.

CROWN POINT ROAD. Crown Point Road was built by the British in 1759 to get supplies from the Connecticut River to Lake Champlain in order to help the British in their final push north to drive the French from North America. It opened the area to settlement, and parts were used in the capture of Fort Ticonderoga. Courtesy Crown Point Road Association.

AFTER THE FRENCH AND INDIAN WAR: 1760–1769

Although happy that they won, the British national debt swelled almost five times because of the war—from £30 million in 1753 to £140 million in 1763. The British started to demand that the colonists pay more toward this debt. At first, the colonists were jubilant that the war was over and new land was available.

In the 1730s and 1740s, the Connecticut legislature was beginning to open up the “upper towns” in northwest Connecticut on the east and west side of the Housatonic: Cornwall, Canaan, Sharon and Salisbury. To encourage settlement, inexpensive “rights” were sold. Similarly, an expansion was taking place north in western Massachusetts. Berkshire County was established in 1761, and nine new towns were organized in the 1760s, including Pittsfield, Great Barrington, Williamstown and Lanesboro. Sheffield had already been organized in 1733.

Table 1. Towns chartered under New Hampshire and New York grants west of Connecticut River in what is today Vermont.

| Year | Number of New Hampshire towns chartered | Comments |

| 1749 | 1 | First New Hampshire town: Bennington in southwest Vermont |

| 1750 | 1 | |

| 1751 | 2 | |

| 1752 | 2 | |

| 1753 | 7 | |

| 1754 | 3 | English and French fighting accelerates |

| 1755–58 | 0 | |

| 1759 | 0 | French and Indian War effectively ends |

| 1760 | 1 | Settlers really begin to come to Vermont |

| 1761 | 61 | |

| 1762 | 10 | |

| 1763 | 35 | |

| 1764 | 5 | June: New Ham... |

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- Part I. The Seeds and Forces of Rebellion Are Created

- Part II. The Journey to Ticonderoga

- Part III. The Capture of Fort Ticonderoga

- Appendix I. General Timeline

- Appendix II. Longitude and Latitude Coordinates for GPS Users

- Appendix III. Arnold’s Role

- Appendix IV. Selected Related Historic Sites

- Appendix V. Participant Details

- General Notes

- Bibliography

- Index

- About the Author