![]()

1 A CLEARLY DEFINED FORM

Kay Fisker was born and raised in Frederiksberg, an independent municipality within Copenhagen, in a bourgeois family consisting of his parents and a younger sister, Gerda. His father Asmus Marius Fisker was an apothecary who died at the young age of forty when Fisker was just thirteen years old. Fisker enjoyed drawing as a young boy. He also seems to have been a keen reader, helping his mother distribute books to the members of a reading society she had founded in 1881. Tobias Faber has suggested that the historian H.V. Clausen, who taught Fisker in school, might have inspired him to pursue a career as an architect.1 All in all, Fisker came from a background of educated, bourgeois professionals and grew up in an environment where his artistic, literary and historical interests were being stimulated, even if there were no artists or architects to directly inspire him in his family and its social circle.

Having passed his realeksamen (lower secondary school leaving examination) in 1909, Fisker took lessons at a drawing and painting school run by the artist brothers Gustav and Sophus Vermehren, a preparatory school for admission to the Royal Academy of Fine Arts. Fisker was accepted to the academy’s School of Architecture in the autumn of 1909 at the age of sixteen as one of the youngest students in his class. The academy’s architecture school was small and had only two professors, Martin Nyrop and Hack Kampmann, both of whom ran successful studios representing a national romantic line in Danish architecture. Teaching at the school was in certain regards rather liberal at the time and mainly consisted of individual day and evening instruction. Most of the students worked in architecture studios parallel to their studies or during gap years. Fisker worked several years in the architect Anton Rosen’s office, which was reputed as an inspiring and exciting place to work for young architects in the making. Students would also participate in open public architectural competitions and some, including Fisker, would receive their first commissions even before their formal graduation. Many students had trained in a craft before enrolling at the academy, yet if that was not the case, students were required to take apprenticeships during their first years of study in the academy’s summer break, which lasted several months. Accordingly, Fisker spent some summers as an apprentice bricklayer, which would have contributed to his knowledge and appreciation of craftsmanship and brick detailing, as demonstrated in his buildings throughout his career.

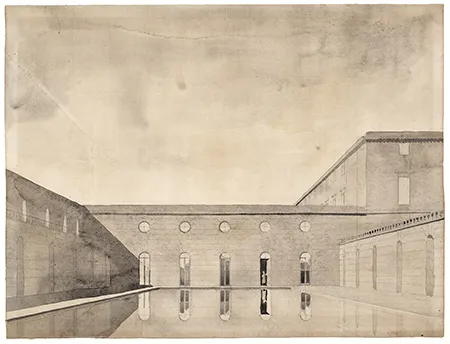

Knowledge of historical styles and the student’s ability to copy and master the stylistic vocabularies of ‘antique style’, ‘medieval style’ and ‘Renaissance’, was essential to the teaching at the academy. The students designed monumental buildings such as palaces and churches, and were neither able to choose the programme nor the style of their graduation project. Fisker’s graduation project, presented in January 1920, testified to this system of teaching: a grandiose neoclassical manor house of a scale evocative of a seventeenth-century princely palace, situated in a vast baroque park full of avenues and long perspectival vistas (Figure 1.1).

FIGURE 1.1 Kay Fisker, Diploma project, 1920. Royal Danish Library – Danish National Art Library/Courtesy of Johan Fisker.

Since the eighteenth century, Danish architects had measured buildings as a way of gaining empirical knowledge of their design, details and construction, yet it was not until the mid-nineteenth century that architecture in Denmark caught their attention. Johan Daniel Herholdt was a pioneer in this regard and brought his academy students to measure castles and manor houses throughout the country. Hans Jørgen Holm turned measurement into an independent and mandatory discipline at the School of Architecture in 1866, including the measurement of manor houses, village churches and classicist market town houses, that is, anonymous, typical buildings, and many of the drawings were published. It supported a growing interest in Danish architectural history and the preservation and protection of historic buildings, in part due to a Danish nationalist awakening just like in many other European countries at the time.2 Apart from Holm’s training in measurement drawing, the academy responded rather late to this attentiveness to Danish architecture. Not until 1910–11 did it establish Den Danske Klasse (The Danish Class) in which the students would design projects such as houses for doctors or foresters, country railway stations, minor churches or village churches, inspired by their studies of Danish vernacular architecture, yet they would almost never design more ordinary urban housing projects.3 The students also organized trips on their own through Foreningen af 3. December 1892 (Association of 3rd December 1892), which published their drawings and arranged lectures and competitions, and increasingly paid attention to vernacular and anonymous architecture such as half-timbered farms and townhouses from the seventeenth to the early nineteenth centuries.4 Fisker took part in these activities during his years at the academy and applied the technique of watercolour painting, which he had learned from Hack Kampmann, on trips around Denmark and to Scania in Sweden, drawing and painting village churches and anonymous architecture.5 As he would later recall: ‘One admires the modest and simplistic forms, the large wall surfaces and towers without spires such as the powder magazines on Amager, Korsør’s coast battery, manor houses such as Sparresholm and Spøttrup (the latter before its refurbishment). One objects strongly to the historical restorations of the preceding period.’6

Danish architecture was in a period of dramatic change during the first decades of the twentieth century. Many architects, turning their backs on the historicist tendencies of the nineteenth century still present at the academy, aimed to involve themselves in more mundane building projects contrary to the monumental schemes devised by the academy under its strict stylistic regime. Akademisk Arkitektforening (Danish Association of Architects) established Tegnehjælpen (The Drawing Aid) in 1906, which provided cheap services to clients and constructors; some of these activities were carried on by the Landsforeningen Bedre Byggeskik (National Association of Better Building Practice, established in 1915). In 1909, a group of young architects who had studied independently with the architect P.V. Jensen Klint formed Den Fri Architektforening (Independent Association of Architects) in opposition to the academy and to the existing association of architects. Povl Baumann was president of the association until it dissolved in 1919.7

Just like the group of architects forming Den Fri Architektforening had felt that something was missing in the academy’s teaching during their years of study, so did Fisker and his fellow students. In a similar vein they formed a group called Kanonarkitekterne (The Cannon Architects) in 1910, consisting of Ejnar Dyggve, Aage Rafn, Otto Valentiner, Andreas Mehren Ludvigsen, Povl Stegmann, Emil Koch, Aksel G. Jørgensen, Ingrid Møller, Volmar Drosted and Fisker. Their aim was to make Danish building culture less dependent on historical styles and more focused on a deep understanding of vernacular architecture, craftsmanship and utility, applying the German word Zweckmässigkeit (expedience) to describe the latter aspect.8 The group was keenly interested in Danish and Nordic architecture, but concurrently inspired by international tendencies in continuation of the Jugend and Art Nouveau movements, which the academy considered aesthetically derivational. Hence, they studied and discussed the works and ideas of contemporary architects such as Henry van der Velde, Hendrik Petrus Berlage, Otto Wagner, Adolf Loos, Josef Hoffmann, Alfred Messel and Peter Behrens. To aid their analyses, the group even gathered a small study collection of old discarded building parts and they also organized small sketch projects on their own. The unofficial leader of the group, Ejnar Dyggve, had grown up in Finland and was able to bring inspiration from this country. Years later, Dyggve recalled the group’s background and agenda: ‘They wanted systematic thinking to leave a mark on the disposition of work and they wanted it to be expressed not only graphically but in writing as well, and they aspired to an intensified sensation of the material’s technical characteristics. They also wanted the changing societal structures of the times to duly influence architectural studies.’9 The group felt that all of this was missing at the academy.

Kanonarkitekterne engaged in the measurement of historic houses to search for insights and models that would inform the development of a truly contemporary architecture, contrary to the historicist programme of the academy. They measured some houses including a manor house and worker’s lodges in Hellebæk, a small village near Elsinore, and several members of the group took part in the measument activities of Foreningen af 3. December 1892. Fisker, Rafn and Dyggve measured a number of eighteenth-century derelict townhouses in Vognmagergade in Copenhagen during the early months of 1910, with careful attention to construction, detailing, window formats, proportions and how the buildings were divided into repetitive bays following their half-timbered construction, resulting in a rhythmic effect. As they stated in the publication of their drawings in 1914, these houses represented ‘a design, in which the reality of the function is directly perceived and expressed’.10 Clearly a statement of the architecture these young students pursued. Kanonarkitekterne felt that measuring historic buildings as part of the academy’s curriculum did not result in a thorough analysis of the fundamental formal and technical principles underlying these structures, principles that ought to form the basis for the development of a truly contemporary architecture. As Dyggve explains: ‘If not in practice, then theoretically, the style we sought was timeless; its idea lay hidden in the shape of the stone axe, in the half-timbered bay of a Danish farmhouse, in the floor plan of the village church and in the constructive design of the cannon.’11 Dyggve implies a search for the more abstract or ideal aspects of architecture, what the group perceived as architecture’s fundamental principles, derived from both historical and contemporary examples. Hence, they strove to unify the aesthetically purified form with a consideration for utility and material effects.

Aesthetically, Fisker and Kanonarkitekterne were influenced by the formalist line in contemporary German art history and aesthetic theory as expressed in the writings of Adolf von Hildebrandt, August Schmarsow, Alois Riegl, Heinrich Wölfflin and Albert Erich Brinckmann. Formalism attempted to develop an analytical, quasi-scientific approach to works of art based on the visual perception of their forms, spaces and material appearances, implying that works of art could be studied independent of knowledge of the life of the artist, of artistic intentions and historical backgrounds. It implied a search for the general aesthetic principles of art rather than its specificities. The influence of German aesthetic formalism, however, was not direct but, as Anders V. Munch has demonstrated, to a large degree mediated by the art historian and artist Vilhelm Wanscher, who had studied in Berlin around the turn of the century and became a reader in architectural history at the academy in 1915 and later a professor.12 Wanscher had published the book Den æsthetiske Opfattelse af Kunst (The Aesthetic Perception of Art) in 1906, arguing that the aesthetic perception of art should base itself on classical values such as the effects of form, light and shadow and the compositional effect of a unified whole, what Wanscher termed ‘the grandiose, clearly defined form’.13 According to Wanscher, the experience of a work of art was like a language that could be learned – by understanding the impression that art provides: ‘The sense of beauty is a product of the artistic culture and it is only developed through a direct relationship with the aesthetically significant qualities of art (or one may choose to call it “form” or “style” or “technique”).’14 It is exactly this pregnancy that Wanscher describes as the classical effect. Pivotal to Wanscher’s aesthetics is an interest in the impression of the overall, in the form and the composition, the combination of parts. The aesthetic experience depends on the empathy of the observer: ‘We carry out an aesthetical piece of work ourselves when we look at a building; and since practice and manual skills are necessary for any type of work, the development of one’s inherent talents by frequently using them is just as important in this field.’15 This applies not just to the singular building but also to the total group of buildings; one may indeed sense ‘the aesthetic pleasure of compiling the various effects into a spatial image’.16 These aesthetic laws were, according to Wanscher, of an eternal rather than individual nature, referring to the universal, homogeneous, well-proportioned and harmonic characteristics of art across epochs and styles.17 Kanonarkitekterne aimed to derive exactly such aesthetic laws from the buildings they were studying and measuring, and according to Steen Eiler Rasmussen, Wanscher would teach the students to strive for refinement rather than beautification.18 Fisker later acknowledged the role of Wanscher and in particular Den æsthetiske Opfattelse af Kunst in the formation of such an aesthetics based on the perception of the building as a clearly defined form, almost an organism, with keen attention to its surrounds and a logical use of materials and layout of the plan according to its functionality.19

Refinement also characterized the works and ideas of another important source of inspiration during Fiske...