The battery was dead, the heater useless; the policemen seated in the patrol car outside 633 Pasteur Street were freezing. Another officer had already taken the dead battery to be recharged, leaving the car’s hood slightly open, and they awaited his return. Bordón sat reading the sports section of the newspaper—just yesterday, Brazil had won the Soccer World Cup—while Sergeant Guzman, in the driver’s seat, watched the street. A truck had parked, and, in the process of removing a filled dumpster from the curb, blocked the lane. Waiting then for the truck to deposit a new, empty dumpster, the motorists to its rear had made their impatience known. When the driver had finally finished the task and departed, the morning traffic began to pour past again, emptying onto Avenida Córdoba two blocks away.

Guzman returned his gaze to the building at 633 Pasteur, where a group of Jewish philanthropic institutions had organized the Asociación Mutual Israelita Argentina. Ever since the bombing of the Israeli Embassy in 1992, organizations affiliated with the Jewish community had received special police surveillance; this morning, Guzman and Bordón were assigned to keep watch.

The building was the tallest on its block, a six-story structure with a black marble façade and bronze-framed double-glass doors. Above the entrance, the marble framed three vertical windows, and above these the four bronze letters were set into the stone: AMIA. Another six-story building occupied by textile importers stood to its left, and to its right, down to the corner with Viamonte, was a line of smaller shops and offices. The Once neighborhood, like Manhattan’s Diamond District, was the traditional Jewish quarter of Buenos Aires. Though a growing number of Korean and Chinese families had arrived in recent years, taking over the fabric and textile stores, several synagogues, Jewish social clubs and theaters remained, and some prominent members of the religious community still lived in Once.

The AMIA building was full of activity on the morning of July 18. Security kept watch of the front doors, searching all bags or suspicious packages entering the building, and most of its four hundred and fifty employees were kept busy: workers at the Treasury on the second floor prepared documents for a meeting of the Board of Directors later that morning, while the rest of their department oversaw the cashier boxes, where debtors arrived to pay installments on their loans and insurance plans. Martin Cano, a waiter for the building, was also preparing for the board meeting, dragging his rolling table onto the basement elevator, laden with a heavy tank of fresh coffee. Mourners had lined up at the funeral department on the fourth floor, looking to provide their loved ones a traditional Jewish burial, while the unemployed gathered outside the employment offices. At that time, the Rec Center for the elderly and the Center of Jewish Documentation were perhaps the only places still empty. Otherwise, much of the building’s administrative staff, with their offices on the upper floors closed for renovations, were stationed temporarily in the theater belowground.

The construction workers carted debris through the lobby to the entrance, where Guzman watched them emerge, ascend a makeshift wooden bridge, and empty their carts into the new dumpster on the curb. AMIA’s Chief of Security, a former Israeli combatant, had ordered the dumpster moved a further two yards from the entrance, in the direction of Viamonte—an order which, though he could not have known it at the time, would prove fateful.

Just then a man knocked on Guzman’s window and bent over to speak. He was a baker, delivering pastries to a shop across the street, and needed to double-park his van. From where he sat, Guzman could see the trays piled in the back of the van. The man’s son was with him. Guzman waved, and just as father and son began their work, a silver car parked behind the van, appearing to suffer from mechanical issues. The driver stood at the opened hood, instructing one of his companions inside the car. Guzman knew the driver: he ran a print shop nearby. The car was filled with his materials. Guzman stepped out of the patrol car. He told the printer to hurry—two vehicles double-parked on such a busy street as Pasteur hindered the traffic considerably—and entered the Café Kaoba. The café was crowded, but he spotted an empty table at the far end of the room. “Un cortado,” he said to the girl behind the counter, and watched the street through the front window as he waited.

The baker and the printer were still parked outside; a janitor for the building facing AMIA looked on the scene as he washed down the sidewalk with a hose, and the municipal street sweeper passed by, pushing his trash barrow ahead of him, filling it with a mixture of garbage and mud from the sidewalk as he went. A mother walked quickly past, in the direction of Calle Tucuman, dragging her five-year-old son along by the arm. He trotted at her side, trying to keep up. She was glad they had caught the subway to the Pasteur station: they would be on time for the boy’s kindergarten. She looked once more at her watch—9:53—and in the next instant felt an overpowering heat press upon her back.

Nobody really knows what happened next, but from various accounts we have gathered an idea of events.

Ana, a sociologist for AMIA, was on her way to the technical area on the second floor, to use one of the building’s word processors, when the building began to shake uncontrollably. Pieces of masonry fell through the ceiling, a cacophony of shouts and shattering glass reverberated. Ana threw herself into a nearby emergency door, emerged onto the outdoor terrace, and climbed to an adjacent building, the sounds of terror pursuing her.

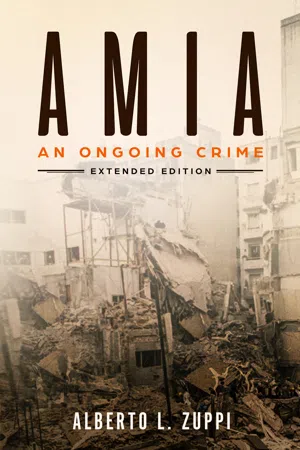

Hugo Fryszberg, in his office on the second floor of AMIA, would recall hearing not one, but two explosions, only a few seconds apart. At the first sound, Hugo’s manager shouted, “Everybody under cover.” Ducking beneath his desk, Hugo felt as though he were slipping into a deep abyss. After the second explosion had ended, he looked up and saw only darkness and smoke. An acrid smell filled the air; it was difficult to breath. Stumbling through the smoke, he met some colleagues, and joined them to rescue a woman whose desperate shouts arose from beneath the rubble. They carried her away, clambering up the debris to an adjacent balcony, and turned to survey the scene behind them. Hugo couldn’t believe it: the AMIA building was gone; he could see the building to its rear through the space it left behind.

A video taken moments later shows people walking in shock through a cloud of dust, vacant-eyed, their clothing shredded. Human remains litter the road; howls and cries mix with the calls of sirens, and the streets fill with a procession of ambulances and police cars. Glass had exploded from every window and door within a three-block radius. A lamp pole had been lifted from its place on Pasteur and stood imbedded in the cement at the corner of Viamonte, a hundred yards away. Rolls of fabric hung like tattered curtains from the broken windows of a warehouse on the corner.

The AMIA building itself had been reduced to rubble. Later, we would learn the reason for the sound of the second explosion, as Hugo heard it: the first had lifted the building into the air, which, falling back to earth, produced a thunderous second roar. The sound of it was heard miles away; a mushroom cloud rose more than three hundred feet overhead.

Police and emergency services arrived several minutes after the explosion, and hundreds of civilians gathered on Pasteur. Gradually, the search for survivors began. Nobody was really in charge; a confusion of emergency officials and volunteers searched for survivors amidst the rubble. Several orthodox Jews, dressed in their traditional attire, ascended the rubble. Policemen, firemen, and civilian volunteers made several chains of baskets: for cleaning debris, distributing water bottles, and later, sharing food. From time to time, people at the top of the pile shouted to the crowd below, demanding silence. They needed to hear whether somebody was calling to them from beneath the rubble. One stretcher after another was pushed and dragged to the top of the pile.

Many people within the building—the laborers and the mourners, the unemployed and several of the AMIA staff—died instantly. Across the street, bits of debris had buffeted the baker and the printer like bullets. Apart from the lucky ones, who found an immediate exit to an adjacent terrace or roof, the survivors of the AMIA staff were buried beneath the rubble and rescued several hours later—by which time many more died of the injuries sustained. News footage that evening showed emergency forces working to uncover a survivor, when a large piece of masonry hanging from the remaining foundations came loose and fell, crushing one fireman. The trapped man was rescued more than thirty hours later, but would die, too, in the ambulance.

Guzman and Bordón survived: the former was propelled through the rear wall of the Café Kaoba, into the men’s restroom, while the patrol car’s raised hood absorbed much of the impact, miraculously protecting Bordón. The street sweeper fell into the empty dumpster and was found several hours later—in shock, but alive. In an apartment building on the other side of the block, a woman on the top floor returned home to find all of her furniture overturned; her small pet laying injured beneath her bed.

The injured were sent initially to nearby hospitals, and then redirected to more distant hospitals and other institutions as these overcrowded. No group oversaw this process. Nobody knew how many were injured. Logically, it must be presumed that when somebody was reported injured, he was within range of the explosion; but no testimonies were taken from these injured witnesses. Corpses and human remains were sent directly to the morgue, two blocks away, for identification. Many, however, were beyond recognition; even today, some remains rest unidentified.

The number of people killed in the explosion and its aftermath is estimated ...