- 112 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

American Divergences in the Great Recession

About this book

Globalization is quite different from internationalization: the by-now global market economy overwhelmed the sovereignty of the old national states. Close to the 2007 crisis, some de-coupling effects were consequent in most developed countries in comparison with the ex-Third World. Latin America seemed to entail a "divergence" with the First World, as unlike the past, it was not hit by the financial crisis, but old historical fragilities invalidated the short positive cycle produced by high international prices. This work deals with this crisis and its basic differences from the older crises of the Thirties and Seventies.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access American Divergences in the Great Recession by Daniele Pompejano in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Modern History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Without Gold and After the Dollar

DOI: 10.4324/9781003025429-1

1.1 The Setting of the Story

Since the summer of 2007 and 2008, the neoliberal model has been hit by a crisis in the United States, which manifested itself in a nonetheless different dynamic at the global level. In October 2009, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) compared the economic performance of some emerging economies amid the global crisis: Latin America1 showed that it had aligned itself with the world average for GDP reduction, unlike the past when crises had produced far more devastating effects (Kincaid & Collyns, 2003). The best performance was due to lower external vulnerability, fiscal balance, and counter-cyclical monetary policies through which five countries in particular (Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Mexico, and Peru) had succeeded – even during a global crisis – to save at least four percentage points of GDP.

But, the real reason for unprecedented economic stability was a much more solid and reliable institutional political environment than it was in the past. By the second half of the 1980s, liberal and democratic rules had been restored in the Latin American countries, and important neoliberal reforms had been set in motion. According to the IMF, financial and trade liberalisation, together with the reduction of inflation and fiscal rebalancing, would have allowed those economies to exploit the positive cycle experienced by the United States, its effects in the following decade, from the financial sphere to the real economy. Indeed, the most explicit reference in the IMF document, rather than the 1990s, is related to the cycle inaugurated in the early years of the new century and almost the entire first decade. In this regard, the IMF also pointed out that five countries (Chile and Venezuela being the largest) had not been forced to resort to IMF support since the mid-1990s, and others, including Argentina and Brazil, had even managed to pay their exposures to the IMF three years in advance. Finally, in the case of the 2007 crisis, only the small Central American economies, and Mexico and Peru, and Santo Domingo in 2009 (Domínguez, 2010) had been forced to resort to the IMF.

It also draws attention to the fact that, except Brazil and Mexico, public spending to support development has not even affected – according to some scholars – the so-called neutral interest rate, i.e., the level of interest rates corresponding to an economy of full employment and stable inflation (IMF, 2012; Magud & Tsounta, 2012). Again, according to the IMF, other Latin American economies had flexible margins for increasing the supply of money and launching counter-cyclical policies if necessary. Whether they were economies that operated at a regime of underutilisation of certain factors or full employment trends and stable inflation, what was indicated upstream of the positive cycle was the realisation of the rising prices of Latin American exports and the allocation of resources to growth (Kincaid & Collyns, 2003).

However, the optimism of the IMF, as revealed by analyses conducted between 2009 and 2012, was cooled a few years after the appearance of a new critical phase. This time, it was the Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC) that, summarising the current dynamics in its Economic Study (Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean, 2015), denounced the highly negative impact of the crisis that has arisen since 2011–2012 on GDP, gross capital formation, participation in world trade, public debt, but – and this is noteworthy – not on the stock of Latin American reserves (Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean, 2008, 2015; United Nations Conference on Trade and Development, 2013).2 The elements are to be considered from a medium-term perspective.

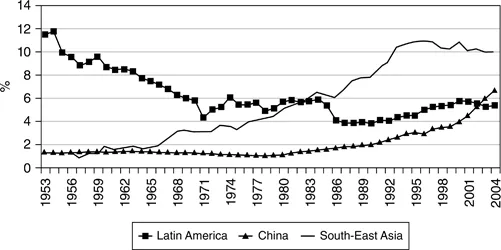

Growth and the ability to manage the crisis with controlled inflation rates were, however, a turning point in countries historically afflicted by double to five-digit inflation rates between the 1970s and 1980s. During the following decade of the 1990s, in the scenarios of a return to democracy, the Latin American governments had to formulate tax adjustments and drastic measures to reduce inflation, with serious repercussions on employment levels, on the prices of the food basket, on the polarisation of incomes, and on levels of poverty. In this regard, it is useful to recall how the abundance of financial resources and flexibility in productive relations were then assumed and perceived as the driving force behind a constant increase in well-being and the volume of trade. However, if we take participation in world trade, the indicator concerning Latin America is high as a whole in the phase that embraces the post-war period and up to the Korean War, but it progressively descends in the period of national populism and the ISI. In the course of the 1970s, it stays at a value of half of the previous values until it is further reduced in the course of the 1980s because of the productive stagnation caused by the debt crisis. Finally, it tends to go back between the 1990s and the early years of the new century at an average rate well below the world rate, which, from the 1990s, grew 1.5 times more than the world's GDP. This was a sign of speeding up of trade produced by liberalisation (United Nations Conference on Trade and Development Statistics, 2015). This is shown in Figure 1.1.

Figure 1.1Latin American, Chinese and South-East Asian Involvement in International Trade in Percentages (1953–2004)

Source: Produced with Data from the World Bank Included in Castilla et al. (2005). Courtesy of CAF

If we extend the analysis of the data beyond the chronological limit indicated in the figure and into the first decade of the twenty-first century, the participation of Latin America in world trade would be 7.4%. Although valuations differed, various sources indicate a positive trend, but not as huge as those experienced by other Asian economies and emerging markets. This growth can be broken down by sectors: between 1990 and 2015, exports of agricultural and mining products remained between 14% and 15%, albeit with fluctuations. The processing of agro-mineral derivatives was maintained between 6 and 7%, but production using middle technology has grown markedly from 4% to 12% in 1990 to 2015, respectively.

In sum: the growth figures are basically due to the rise in raw material prices, especially if we consider that the increase in value of Latin American exports between 1990 and 2009 was accompanied by a reduction in volumes (Rosales, 2015; Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean, 2016).3 As a result of the increase in reserves and the consequent appreciation of the Latin American currencies, exports became less competitive and the current account deficit increased. Although the debt has grown again, it is very different from the past in terms of quantity and quality. External financial flows have been abundant and – as we shall see – decisive in sustaining growth. Latin America has been a unique region in having recorded only cyclical contractions in incoming financial flows following the crisis that exploded in 2007 (Anderson & Cavanagh, 2002; Vos, Ganuza & Morley, 2006).4 What is more, as pointed out by ECLAC, financial and trade liberalisation seems to have rather produced and shown synchronisation between incoming financial flows and their use in the real economy (Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean, 2012). This would constitute a source of originality for the region in the completely new scenarios of financial globalisation in which the circuits of the real economy and finance, of commercial and financial transactions, have spread, producing asymmetrical effects among geographical areas and sectors.

Hence, in the 2007 crisis, while the United States was hit by a recessionary crisis, the subcontinent, in contrast, was experiencing an apparent downturn conjuncture in an expansionary cycle that had begun roughly after the 1990s. The point is to understand to what extent the different trends in the two parts of the American continent were related to the trend of the real economy, its fundamentals, international trade, and the comparative advantages exploited by the Latin American economies. And how much, conversely, the doping of the financial economy, monetary and speculative factors have intervened to distort or sustain the dynamics of growth, producing the global 2007 recession that emerged in the United States.

Asymmetry is perhaps an excessive term used to indicate rather divergent paths, in which internal and international dynamics are intertwined, less sensitive to the historical reasons of geopolitics, and more difficult to classify in systemic logic. On a lexical, the term decoupling would be more effective, as it expresses different trajectories, perhaps the discrepancy of the peripheral economies compared to the more developed ones. Analysing the most recent trend of the main Latin American economies, it would in fact be possible to record a sort of decoupling from the centre, which, in contrast, is going through a phase of the crisis.

The terms of the problem can be framed in the post-1989 scenarios, when the international policy of the United States appeared uncertain in focusing on the changes that have taken place. A debate has been sparked about the American “decline”, of which the Great Recession would have made manifest certain elements since 2007. Indeed, critical forces have thus paradoxically fallen on the United States, which those critical forces had originally fuelled by trusting in the expansive capacities of the liberalised market.5 Asymmetry is, on the other hand, a category that is too bound up with the dualistic perspective of the theories of dependence. In the 1950s and up to the 1970s, there was a widespread opinion that a bond of reflex and dependence, of asymmetry, had been consolidated between the centre and the periphery, even since the conquest of the Americas.6 And that historically in times of crisis, the effects were reflected mechanically from the North to the South.

The 2007 crisis would seem to disprove the paradigms of dualism: while the North was hit by the crisis, the South diversified markets of its exports and financed its economy by drawing on resources offered on the international market. It is, therefore, worth clarifying our thesis: the crisis of 2007 proved to be unprecedented for the scenarios in which it manifested itself, but not for the forces that fuelled it, and explains differently the economic cycle in the course of which it exploded. Perhaps the category of divergence – spread by the most recent literature on the subject – allows for greater flexibility of use in global scenarios where unilateralism and polycentrism are discussed.

1.2 Political Fears

To the problematic points concerning the economic dynamics triggered by globalisation, we can add brief but significant elements of reflection typical of the domestic and international political dimension to which the economic indicators implicitly refer. The 2014 UNDP report recorded a progressive improvement in political relations at the global level: the percentage of formal democracies had increased from less than a third of the countries that benefited from liberal-democratic regimes in 1970 to 50% around the mid-1990s, up to three-fifths in 2008, even though many hybrid forms of political organisation had emerged. If in the mid-1980s, 45% of the world's population lived under authoritarian regimes, the percentage in 2000 was reduced to 30% (United Nations Development Programme, 2000, 2014) even though new-generation indicators – such as empowerment and gender status or the sustainability of growth – still showed strong imbalances. The same UNDP report, despite noting a general improvement in the Human Development Index (HDI) since 1990, had to acknowledge a sharp slowdown between 2008 and 2013. In the 2014 report, the emphasis was placed on the sense of precariousness in the living standards achieved, in personal security, in the political and environmental sustainability of models of coexistence and growth (United Nations Development Programme, 2014).

The above-mentioned UNPD indicators refer more to internal relations. If we turn to international relations: between 1945 and 2011, more than 50 internal and international conflicts broke out, half of them after the ideological “detoxification” of 1989. Apart from the war that devastated the Balkan states in the 1990s, the rest of the 25 major conflicts recorded since 1945 have taken place in the south of the world, from the Middle East to the Far East and Africa, and in the regions and former states of the USSR in the 1990s.

The ambivalence of globalisation is explicitly expressed by the Global Trends Report published every four years on behalf of the CIA and the US National Intelligence Council. The tendencies glimpsed in the ongoing processes are perceived as threatening to US domination and hegemony. Among all of these, it is worth recalling the warnings – constant between the 1999 and 2014 editions – regarding the unbalanced distribution and use of resources. They both produce manifest or latent tensions concentrated above all in the so-called Great Middle East, in South Sahara, and Latin America. Differentiated access to scarce resources threatens the balance in international relations that neoliberalism is thought to have contributed to relaxing. What's more according to United States intelligence analysts, this would have given rise to a de-territorialised enemy (terrorism) feared only in the 1999 report, which seems to figure as an explicit obsession in the most recent one in 2014 (National Intelligence Council, 2000, 2012).

Both the reports warned of the re-emergence of nationalist feelings and policies: globalisation-induced imbalances would produce exasperations of identity, obstacles to i...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Series

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- List of Figures

- List of Tables

- Introduction: The Dilemma of Currency

- 1 Without Gold and After the Dollar

- 2 Cycles of Crisis

- 3 Meanwhile, in Latin America…

- 4 The “Invisible Hand” of the Market

- Conclusions: “Do Those Who Don’t Obey the Rules Win”?

- Index