eBook - ePub

Housing Improvement and Social Inequality

Case Study of an Inner City

Paul N. Balchin

This is a test

Share book

- 276 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Housing Improvement and Social Inequality

Case Study of an Inner City

Paul N. Balchin

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Originally published in 1979, this book discusses housing improvement, and particularly its effects upon the residential population of the inner areas of West London. The economic and social rationale is explained, and the role of landlords, developers and local authorities is analysed. The book concentrates both on the defects of the improvement process as a whole, and on the application of housing legislation within a specific geographical area. Housing improvement is related to the debate about the inequality of wealth by implicitly questioning who benefits and who loses from improvement policy.

Frequently asked questions

How do I cancel my subscription?

Can/how do I download books?

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

What is the difference between the pricing plans?

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

What is Perlego?

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Do you support text-to-speech?

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Is Housing Improvement and Social Inequality an online PDF/ePUB?

Yes, you can access Housing Improvement and Social Inequality by Paul N. Balchin in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Physical Sciences & Geography. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

1 Introduction

Residential Location Theory and the Problems of Private Housing in the Inner Cities

In an attempt to explain why there are extensive areas of deteriorated residential properties in our cities and to comprehend the consequences of housing improvement policy in a specific area, it is necessary initially to analyse the working of the urban housing market and to consider some of the interdependencies which define the urban system. The housing market is unlike the market for other goods and services in that the product is spatially unique, very durable and heterogeneous. In considering the housing market, the spatial distribution of the product is one of the principal factors of the analysis. But the market is not perfect; government intervention in the form of zoning restrictions, rent control or regulation, subsidies and public housing development have greatly influenced the forces of supply and demand. The institutional arrangements for mortgage finance and income tax allowances on mortgage interest payments have also had a major effect. In this analysis these factors will be mainly ignored and simplifying assumptions will be made. These are: an urban area with a single centre, perfect knowledge on the part of sellers and buyers, rational behaviour and the assumption that the seller or producer of the dwellings aims to maximise revenue, and the buyer aims to maximise his satisfaction or utility. It is recognised that although:

the internal structure of any city is unique in its particular combination of detail...in general there is a degree of order underlying the land use patterns of individual cities. (Garner, 1970, pp.338-339).

The Concentric Zone and Sector Models

The rapid growth of cities in the United States during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries was characterised by an outward ‘invasion’ of low income households into formerly high income areas. The concentric zone model illustrates this process, and has often been used to explain the pattern of urban land uses throughout the industrialised world. The model is particularly relevant to the problems of the inner city.

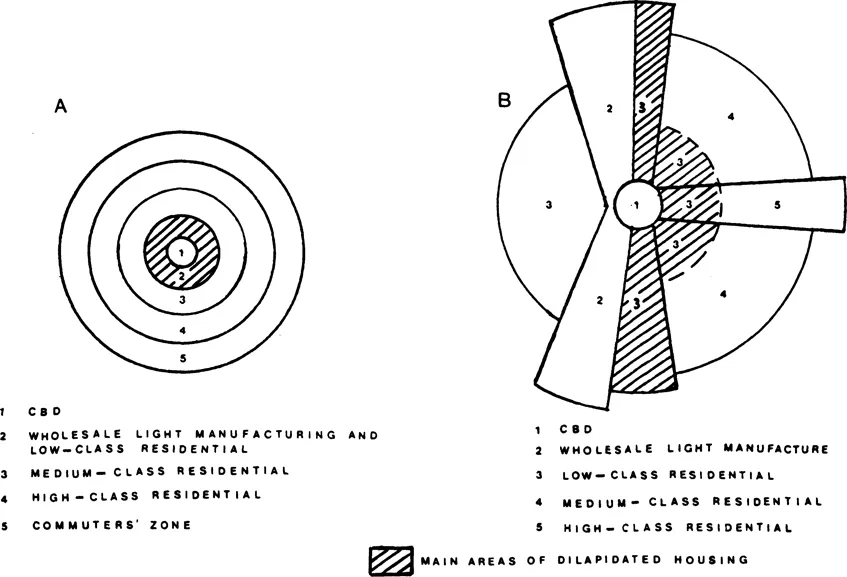

It is assumed that accessibility and values diminish with equal regularity in all directions from a central point in an urban area. Distortions caused by variations in topography and differential accessibility are ignored and it is argued that patterns of land use will be arranged in regular concentric zones. Based on his studies of Chicago, Burgess (1925) stated that at any moment of time, land uses within the city differentiate themselves into zones according to their age and character (Fig.1 A).

Figure 1.1 The concentric zone model (A) and sector model of urban structure (B)

The transitional zone is the main area of dilapitated housing, and it also includes light manufacturing, wholesaling and other (mainly small) businesses. Blighted conditions and slums result in much of this zone being referred to as ‘the twilight area’. It is the zone in which there is the greatest need for renewal. It surrounds the central business district (CBD) which forms the heart of the city’s commercial, cultural and social life as well as being the focus of urban transport. The transition zone is surrounded by the low class residential zone which, according to Burgess, is:

inhabited by the workers in industries who have escaped from the area of deterioration but who desire to live within easy access of their work (p.55).

This in turn is surrounded by a zone of middle and high income housing characterised by single family dwellings. Around this there is an outer zone beyond the city limits, a commuter belt of suburban and satellite communities. Burgess acknowledged that neither Chicago nor any other urban area fit exactly into this ideal scheme.

With population and economic growth, urban land use is influenced first by centripetal forces of attraction, second by centrifugal forces of dispersion and third, by forces of spatial differentiation. There is, according to Burgess, the:

tendency of each inner zone to extend its area by the invasion of the next outer zone. This aspect of expansion may be called succession, a process which has been studied in detail in plant ecology .... In the expansion of the city a process of distribution takes place which sifts and sorts and relocates individuals and groups by residence and occupation (p.56).

A result of this process is that the oldest residential property will be centrally located (in parts of the CBD but mainly within the zone of transition) and the newest housing will tend to be in the commuter zone. Whereas the higher income groups are able to afford the newest property and so locate mainly in the outer urban area, the lowest income groups are only able to afford the oldest property which will be mainly within the ‘twilight’ areas of the transition zone.

Unlike the concentric zone model, sector models assume that urban land use is conditioned by the pattern of radial routeways. Variations in accessibility cause sectoral difference in property values and the arrangement of land uses. Hoyt (1939) hypothesised that similar land uses concentrate along particular radial routeways to form sectors (Fig.1 B).

A low income residential sector would extend outwards by the addition of new growth on its outer arc. The same process would occur on the outer edge of the high income sector, although Hoyt (like Burgess) explained that as residential structures deteriorate and become obsolete with the passage of time they are ‘invaded’ by lower and intermediate rental groups who replace higher income households who have mainly moved to the outer edge of their sector. But Hoyt noted that the inner areas still attract a few high income households:

de luxe high-rent apartment areas tend to be established near the business centre in old residential areas .... When the high-rent single family home areas have moved far out on the periphery of the city, some wealthy families desire to live in a colony of luxurious apartments close to the business centre (p.118).

Evans (1973) suggested that as the size of the urban area expands so the proportion of the high income group who wish to live near the centre increases:

as the size of the city increases .... so the distance from the centre to the edge of the city increases, and so the cost of giving up proximity to the centre increases relative to the benefit of living in the high income neighbourhood at the periphery. For both these reasons, the large city is likely to have a high-income neighbourhood, at, or near, the centre, while in a small town all members of the high-income group will locate in the outer part of a sector of the city (p.132).

It can be assumed that both on the periphery of cities and within the central areas high socio-economic groups (and, to a diminishing extent, other groups) will pay a higher price or rent for a location amongst others in the same group.

Stone (1964) noted that the value of land in London generally falls regularly with distance but in the case of areas with special attractions as residential locations – such as Hampstead – the rent gradient is disrupted. This suggests that in order to locate in a high income neighbourhood a ‘neighbourhood premium’ has to be paid over and above the ‘normal’ rent or price. The premium is zero at the edge and usually highest in the centre, the whole neighbourhood perhaps being topographically attractive, for example being on high ground or on a river front, or being very accessible to central area employment and services. In most cities there will be some high income households who find their optimal location in the intermediate areas of cities and who group themselves into neighbourhoods at various distances from the centre. Maximum benefit will be realised if these neighbourhoods coalesce into a single sector of the city – an underlying factor causing the creation of high income sectors even when the city is very large, examples are the Knightsbridge/Kensington and Hampstead/Highgate sectors in London.

With the increased cost, time and inconvenience of commuter travel since the 1950s, the process of outward ‘invasion’ described by Burgess and Hoyt has been supplemented by an in migration of higher income households willing to pay a neighbourhood premium to acquire accommodation in the inner city. A consideration of the relationship between commuter costs and housing costs by means of trade-off models provides the rationale underlying this recent trend.

Trade-Off Models

Instead of regarding the location of a household as being determined by the availability of housing, economists in the 1950s began to assume that a household would find its optimal location relative to the centre of the city by trading-off commuter costs (which mainly increase with distance from the centre) against housing costs (which generally decrease with distance from the centre). It was recognised that a continual trade-off outwards was impossible, Schnore (1954) assuming that:

the maximum distance from significant centres of activity at which a household unit tends to locate is fixed at that point beyond which further savings in rent are insufficient to cover the added costs of transportation to these centres (p.342).

Further versions of the theory were developed by Hoover and Vernon (1959), Alonso (1960, 1964) and Wingo (1961a, 1961b). Alonso (1960) argued that households choose their location to maximise their utility and in so doing balance:

the costs and bother of commuting against the advantages of cheaper land with increasing distance from the centre of the city and the satisfaction of more space for living (p.154).

Adapting the classical theory of economics, Alonso (1964) devised an individual’s bid-rent curve, and argued that an individual’s income was a function of his expenditure on land, the commuting costs of travelling from his home to the centre of the city and his expenditure on all other commodities.

where

Y | = | income |

Pq | = | price x quantity of land |

t | = | distance from the centre of the city |

K | = | commuting costs per unit of distance |

PZz | = | all other expenditure |

The price of land declines with distance from the centre of the city while commuting costs rise. As a househol...