![]()

HELLS AND UNDERWORLDS

Welcome to hell. Or, in the words glimpsed by Dante as he passes through the gates to the Inferno: ‘Abandon all hope, ye who enter here.’ It was this imagery that inspired Auguste Rodin to conceive his famous sculpture The Gates of Hell, an infernal doorway through which the imagination of the viewer was invited to wander. Historically, there have been a number of ‘true’ (certainly truly feared) earthly portals to the hells and underworlds of various faiths.

While the entry requirement of expiration is invariably the same (though not always a hard-and-fast rule, as we shall see), numerous features of real-world geography have played the part of nexus between earthly and spiritual realms. To reach the Hades of antiquity, Kingdom of the Shades, one can follow in the footsteps of Orpheus and Hercules and visit the Cape Matapan Caves on the southernmost point of the Greek mainland; or the Necromanteion of Ephyra at Mesopotamos. Volcanoes too have long been associated with entrances to the fiery underworld – the Icelandic stratovolcano Hekla was feared in Christian tradition as the egress to Satan’s fiery pit. In China, a look at hell can be found in municipal form at Fengdu, ‘City of Ghosts’, where landmarks include Ghost Torturing Pass and Last Glance at Home Tower, and where statues of demons performing their daily tortures can be found around the town.

But what exactly are the workings of these realms of which these portals offer mere glimpses? Any exploration of global afterworld belief must launch in Africa, specifically with the ancient culture possessing the most ornate death-worship practices and elaborately imaginative post-death worlds to have ever ignited the minds of men.

![]()

THE ANCIENT EGYPTIAN DUAT

When we think of the ancient Egyptians, we think of death. This is because of what has survived of their culture, which arguably more than any other obsessed and luxuriated in the ritualised treatment of their dead. The buildings of everyday Egyptian life made from reeds, wood and mud bricks have long since perished; but the stone pyramid tombs of the pharaohs have resisted the violence of millennia to define our image of their ancient creators. Mummified corpses, their preservation considered essential for a contented afterlife, still lurch their way around modern popular culture. The most famous relics called to mind when speaking of ancient Egypt are all funereal in purpose. The pyramid tombs of the ancient pharaohs and their various burial contents all served some use in either ushering one to, or helping one prosper in, the Duat (underworld).

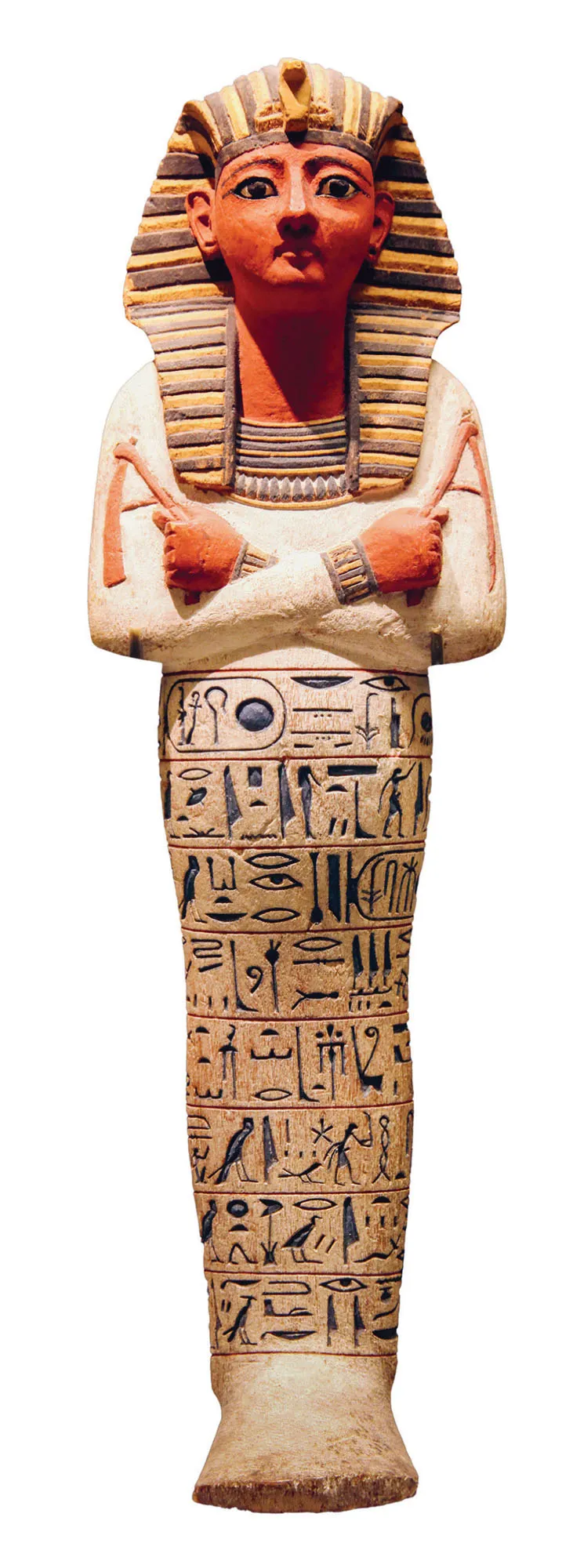

One of the most commonly uncovered types of artefact, the ushabti figurine, was designed for just this purpose. The doll-like figures (see example shown on page 22) were usually inscribed with the sixth-chapter text of the infamous Book of the Dead (the original title of which more accurately translates to the chirpier ‘Book of Emerging Forth into the Light’), a funerary text of magic spells compiled by numerous priests across 1000 years to assist the deceased’s journey through the Duat. The figurines were scattered among the other goods in the grave to operate as assistants to the deceased in the next life. (Inscriptions on their legs announced their cheerful readiness to perform this servile task.) The abundance of ushabti is closely followed by that of scarabs, the beetle-shaped amulets and administrative seals that, by the early New Kingdom, were copiously deployed as part of the ritual protection items guarding a mummy in its tomb.

The ultimate goal of the deceased Egyptian was to reach the blissful Kingdom of Osiris and the heavenly A’aru, or the ‘Fields of Rushes’ (see page 150), the reward for terrestrially well-behaved souls. Decorative scenes of this lush place were carved and painted hopefully on the walls of tombs, such as that of Menna, an inspector of royal estates buried in the Valley of the Nobles, near Luxor. (Fret not, potential resident of noble blood, the luxurious fields of wheat will be worked for you by the ushabti helpers.) But to reach this paradise, the deceased have to journey through the hellish Duat underworld until they reach the grand Hall of Ma’at for ‘the weighing of the heart’, a judgement performed by the dog-headed god Anubis, under the watchful gaze of Osiris, king of the underworld.

It is crucial to follow every instruction provided in the Book of the Dead to successfully pass this judgement – including memorising the forty-two chimeric gods and demons that one will encounter on one’s journey, as well as the itinerary of halls that one passes through. The deceased must confirm they have not contravened any of the possible forty-two crimes that would bar entry – ‘I have not reviled the God; I have not laid violent hands on an orphan; I have not done what the God abominates… I have not killed; I have not turned anyone over to a killer… I have not taken milk from a child’s mouth; I have not driven small cattle from their herbage…’ and so on, until the full confession is made. Anubis then performs his judgement, weighing the heart of the deceased against a feather, which symbolises the Egyptian concept of justice, harmony and balance known as ma’at. A righteous heart is as light as air. Any heart found to be heavier than the feather was rejected, and devoured by Ammit, the eater of souls – these unfortunates simply ceased to exist. The souls that passed the test are permitted to travel onward, to A’aru.

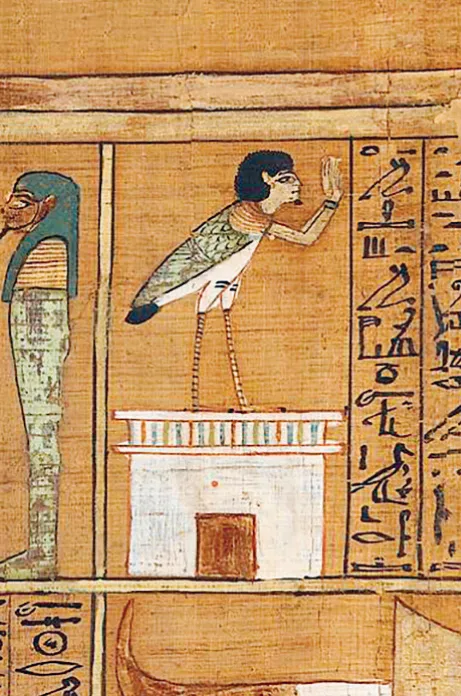

A detail from the Book of the Dead of the Theban scribe Ani, created c.1250 BC, depicting the human-headed, bird-bodied ba of the deceased, one of the imagined forms of the human soul.

An ancient Egyptian papyrus depicting the journey into the afterlife. Officially entitled Guide to the Afterlife for the Custodian of the Property of the Amon Temple Amonemwidja with Symbolic Illustrations Concerning the Dangers in the Netherworld.

One of the coffins of Gua, physician to the governor Djehutyhotep, dated to 1795 BC. The painted floor shows the ‘two ways’ of land and sea that the dead could take to reach the afterlife. The twisting lines form a map of the underworld to help the deceased reach the afterlife. A false door was also included, to allow the ka (spirit) of the dead to escape.

Even if one follows every instruction offered in the Book of the Dead, and other similar texts, it is still not an easy journey to the Other World. The wandering dead have to negotiate both hostile terrain and spiritual booby traps. The tortures and punishments that fill this network of chambers, halls and shadowy corners are physical and often bloody; but most curious is the inverse gravity of the realm.

Just as the Fields of Rushes is a paradise of exaggerated earthly perfection, so the Egyptian netherworld is a mirror image of natural order – the sinners, now in the underworld beneath the flat disc of Earth, must surely walk upside down as they tread the underside of the living world, otherwise they would simply fall off. This, it was believed, forced one’s digestion to be reversed, meaning excrement would cascade from one’s mouth. In utterance 210 of the Pyramid Texts, the oldest Egyptian set of funerary and magical texts, we find reference to a pharaoh crossing into the afterlife and demanding a meal of roasted calf, then exhibiting anxiety that this could lead to disastrous results when combined with walking upside down: ‘What I detest is faeces, I reject urine… I will never eat the detestableness of these two.’

There is a lake of raging fire to avoid (a common feature of so many hellscapes), which is used like a giant barbecue cooker by hungry demons lying in wait. The wandering deceased should also avoid the underworld baboons – considered a mystical animal by the Egyptians – which are fond of decapitating unwary visitors. Beware too the ravenous hell-swine, crocodiles, serpents and wild dogs that also haunt the dark plains. ‘We find in all books about the Other World,’ wrote the Egyptologist E. A. Wallis Budge, ‘pits of fire, abysses of darkness, deadly knives, rivers of boiling water, fetid exhalations, fire-breathing dragons, frightful monsters, and creatures with the heads of animals, cruel and murderous creatures of various aspect… similar to those from early medieval literature. It is almost certain that modern nations owe much of their concept of hell to Egypt.’

A ushabti (funerary figurine) depicting Ramesses IV, made sometime between 1143 and 1136 BC during the Twentieth Dynasty of Egypt (1189-1077 BC).

An illustration from the Book of the Dead of Hunefer, a scribe of...