![]()

The Female Side of Evolution

Anthropologist

Sarah Hrdy

on motherhood

NOT MANY PEOPLE HAVE THOUGHT as much about what it means to be a mother as Sarah Hrdy has. In this emotionally charged domain, the American anthropologist is considered an authority. But she herself describes the focus of her career with a strange distance, as if she wanted to steer clear of any hint of sentimentality: She sees herself as a “mammal with the emotional legacy that makes me capable of caring for others, breeding with the ovaries of an ape, possessing the mind of a human being.” But Hrdy is anything but a cold person, and she must have been plagued often enough in her own life by the question she poses: “What does it mean to be all these things embodied in one ambitious woman?”

Born in 1946 in Dallas, Texas, she studied anthropology at Harvard and made a name for herself with research on the social life of the langur monkeys on the holy Mount Abu in North India. In 1984 the University of California, Davis, appointed her professor of anthropology. But she left her academic career when she was only fifty, “eager to continue research and writing while seeking a more harmonious balance between work and family.” Currently, she lives on a farm in northern California, where she grows walnuts and writes books.

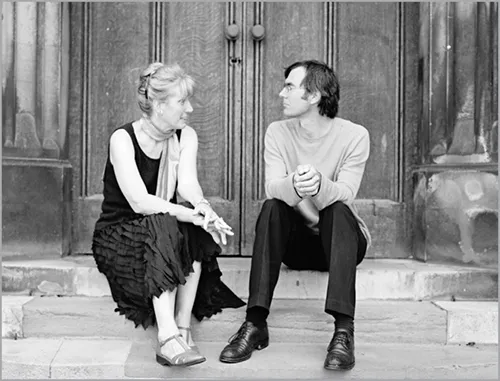

We met at Cambridge, England, on the occasion of the Darwin anniversary festival. Hrdy spoke softly and hoarsely, now and then struggling for control of her vocal cords. Several lectures on the female side of evolution had nearly cost her her voice.

Professor Hrdy, how do you remember your mother?

She was a very beautiful, very smart, and very ambitious woman.

You once described her as “by some standards, an appalling mother.” What did you mean by that?

Well, her position in society was more important to her than her kids. For us, there was a constantly changing succession of nannies, plus she subscribed to the view then common among educated mothers that babies were born blank slates, needing to be shaped. Picking up a crying baby would just spoil her, conditioning the child to cry more. Unquestionably though, I loved her and later in life felt very close to my mother, having learned to understand the constraints she herself confronted and how she herself had been reared—in a long line of mothers gradually losing the art of nurture.

Your books give the reader the impression that no human relationship is anywhere near as fraught with tension as the relationship between a mother and her children.

Under some circumstances, a mother can devote herself completely to her children. But often the mother herself lacks support, or she has to divide her love among several children, or she has other things she needs to do. Human mothers have always confronted such trade-offs. Maternal ambivalence is as natural as maternal love. Yet it’s been hammered into us that unconditional and self-sacrificing maternal love is “normal,” ambivalence considered pathological. It’s assumed that mothers should readily turn their lives over to their little “gene vehicles”. . . .

As some spiders do.

Think of Diaea ergandros. As soon as the young of this Australian species have hatched, the mother undergoes a strange paralysis. She then secretes a substance that liquefies her own body. The mother turns herself into an edible slime—the first nourishment for her offspring, and it’s a good thing, too, since being less hungry, the spiderlings are less likely to cannibalize each other.

You yourself have two adult daughters and a son. Are you familiar with that feeling of paralysis—and the fear of being annihilated by your own children?

Oh, yes. But it’s not only as a mother that I’ve felt as if my family might eat me alive; I sometimes felt that way as a daughter as well. The Texas I grew up in was still extremely patriarchal, not to mention racist. Of course, as a young girl I didn’t have the faintest idea of what this fixation with controlling girls was about. It was the same for my mother: She wanted to be a lawyer, but my grandmother insisted that she first make her debut in Dallas society. There she met my father—a great catch, heir to an oil fortune. And that was that.

You don’t lead exactly the life people expect from a wealthy heiress of several oil companies. How did you break away from that background?

Well, as the third daughter in a family desperate for a son, I was the heiress to spare. Because I loved horses, I was allowed to go off to a boarding school known for its riding program. Fortunately for me, that school also took women’s education very seriously. From there, I went to Wellesley College, where my mother and grandmother had gone. I embarked on a novel about contemporary Mexicans of Maya descent, and it occurred to me that it would be a good idea to learn more about Maya culture. So I transferred to Radcliffe, then the women’s part of Harvard, to study under the great Mayanist Evon Vogt. The novel never got finished, but I ended up as an anthropologist. It’s hard to believe how naive I was, but after summers working in Guatemala and Honduras as an undergraduate volunteer on medical projects, I gradually came to understand just how oppressive the political situation was. Continuing as an anthropologist in that part of the world would turn me into a revolutionary—something I was temperamentally unsuited for.

Instead you went to India in 1971 to study langur monkeys. What drew you there?

I vaguely remembered from an undergraduate course that there was this species of monkey in India called langurs, and that, supposedly due to crowding, the males would occasionally kill babies of their own species. Naively, again, I imagined that langurs would provide a scientific case study for how overpopulation can produce pathological behavior. By the end of my first field season, I realized my starting hypothesis was wrong. Female langurs live in groups with overlapping generations of female kin accompanied by a male who enters from outside. Every so often, a new male from one of the roving all-male bands manages to oust the resident male and take his place. Babies were only being attacked when new males entered the breeding system from outside.

So the intruder attacks the babies?

Exactly. By killing the offspring of his predecessor, the usurper reduced the time before the no-longer-lactating female ovulated again. Far from pathological behavior, the male was increasing his own chances to breed.

The babies’ mothers . . .

. . . try to evade him. But the male has the advantage of being bigger, stronger, and incredibly persistent, stalking the mother-infant pair day after day. Occasionally, a young mother would simply give up trying to protect her baby. After its death she will sexually solicit the murderer. To successfully reproduce, females sometimes have to be opportunistic.

Were you able to watch dispassionately?

No, I was distressed. Watching an attack, tears would roll down my cheeks.

Scientists are not supposed to intervene in the process they are studying.

Right. Plus even if I had tried, I could not have stopped what was happening. And yes, I was also fascinated. After all, this was the bizarre phenomenon that I had come to India to try to understand—why were males doing this? Why, instead of sexually boycotting the male who killed the infant, were mothers going along with it?

The killing of babies was conclusive evidence that what happens in nature can be even harsher than we thought. At the time, many people understood Darwin in terms of the idea that in social animals like primates, all the animals behaved so as to promote the survival of the group or the species. According to your findings, however, even among members of the same species, each individual is striving to maximize its own reproductive chances—even at the cost of its own offspring. But why would any mother then mate with the same male who had killed her infant?

Because a female who boycotted the infanticidal male would be at a disadvantage in relation to other females in her group who bred faster. Plus, to the extent that the infanticidal trait was heritable and advantageous, her sons would inherit it.

Sociobiology, which emerged at that time and advocated such theories, was not quite welcomed with open arms.

That’s putting it mildly. Back in the 1970s, opponents of sociobiology characterized it as sexist, racist, and worse—practically Nazi! We described the world in a way that was out of step with the times. Worse for me—because I was a sociobiologist among anthropologists who distrusted evolutionary perspectives, and was also trying to introduce a female-oriented perspective among evolutionists who regarded feminism as hopelessly suspect. I was decried as a double ideologue. However, in my opinion it’s simply better science to take into account Darwinian selection pressures on mothers and infants, and biased science to leave out half the species.

No one can accuse you of that, at least. You’ve studied female reproduction in all its stages—beginning with the sexuality of the langur females.

At that time, the conventional wisdom was that females mate only when they’re ovulating and only with one male. For many animals, that’s true. But I noticed that langur females solicit males for sex even when they’re not fertile and would sometimes leave the troop to solicit outside males as well. Why? No one before had bothered to wonder about these multiple matings, but it has become an important subject of study.

Were you intrigued by this question because you thought the answer would apply to us humans as well?

As interest in the topic grew I was actually invited to speak on nonconceptive sex in nature at a conference organized by the Italian government and the US National Science Foundation about the “meaning of sexual intercourse,” and yes, they clearly had humans in mind. The Vatican also sent representatives. What a tragedy for Catholics and the world that Saint Augustine, on whom the Church bases its policies to this day, was such a poor animal behaviorist! Augustine believed that he could extrapolate from domestic animals to all animals. For many of them, sex actually is confined to the period right around ovulation when conception can occur, but this is hardly universal in nature, and certainly not among many primates.

So what purpose does it serve for the langur females?

Maybe to manipulate information available to males about paternity. Males apparently remember whom they mated with and avoid harming offspring that might just possibly be their own. But how to make females solicit multiple matings? This led me to speculate that the female orgasm—which, by the way, definitely occurs in some other primates as well—originally evolved long, long ago, in a prehuman context, as part of a reward system for multiple copulations. Women have inherited a physiological potential whose workings evolved in a prehuman social and reproductive context very different from that found among most humans today.

You have to explain that.

To mate with multiple partners is a dangerous business for langurs, too. What can motivate a female creature to do that? We’re talking about a pleasurable psychophysical reaction in response to repeated stimulation, which, on top of that, is erratic. Actually the most powerful type of conditioning is when the reward is uncertain. Thus nonhuman primate females were conditioned to solicit successive partners. I doubt that the pleasurable psychophysical reaction that we call orgasm evolved originally in order to promote human pair bonds. If it had, frankly, we would expect the response to be more reliable, to function better than it does. Rather, the female orgasm is far older, a vestige, secondarily conscripted to this new function.

You mean a woman’s climax is as superfluous as her appendix?

Perhaps, or a still-detectable vestige of a former adaptation no longer so strongly selected for—like the grasping reflex of our newborns for the nonexistent fur of the mother. If I’m right, our descendants in spaceships eons after us may wonder why we made such a fuss about this subject.

It’s risky to draw conclusions about humans on the basis of langurs. Can you prove your theory?

No. It’s a hypothesis, and a highly speculative one at that.

In any case, you women pay dearly for your desire. For the sake of reproductive success, a woman can at best use her libido to secure for herself the support of as many men as possible—by keeping them well-disposed toward her with sex and obscuring her fertility. But the better she manages to do that, the more uncertain each man is of his paternity, the less he does for his offspring. The way out for the woman is probably to find an optimal balance between boundless promiscuity and strict faithfulness.

Well, that balance can be different for each species and, among humans, for each culture, and for women in different economic circumstances. Some South American tribes with unpredictable resources, where mothers have no guarantees that a man will be able to provide for his children, or even still be alive or around, have come up with a fascinating cultural solution to an ancient biological dilemma. They subscribe to the belief that during pregnancy the fetus is built up from semen contributed by each man a woman has sex with during that period. These contributors are all considered “fathers” and expected to help provision the mother and her subsequently born child. Research among the Bari people of Venezuela by the anthropologist Steve Beckerman has shown that children with several putative fathers are more likely to survive. Too many fathers could be detrimental, presumably because men felt less responsible. The babies’ best chances of survival actually turned out to be two supposed fathers.

Men in our monogamous culture would be less than thrilled. But that calculation can hardly be applied to a highly developed society, in which almost every baby survives.

Right. Plus, in our society, with a long, long tradition of patrilineal inheritance of property, we have reified and glorified this concept of paternity certainty. But what’s interesting is how much variation there is in how willing human males are to invest in offspring. A few years ago, Time magazine asked me for a brief article for Father’s Day. I wrote that there’s a huge potential for male nurture in the human species, albeit a potential not always tapped. In passing I cited some statistics from the Children’s Defense Fund showing that divorced fathers were more willing to make car payments than pay child support. I got some pretty angry e-mails, and a website was set up for people to directly complain about me to the magazine’s publisher.

The men’s behavior isn’t right or justifiable—but I can understand it.

Of course: If you don’t have a car, you won’t get another woman.

Aren’t you taking sociobiology a bit too far now? It’s possible that some men are quite simply angry with their ex-wives and take out their anger on their children.

Yes, of course. But such anger has a deep evolutionary history as well: The competition between men for women; the attempt to control women and constrain their choices, along with women’s efforts to evade such control—we owe th...