![]()

TALLER TUPAC AMARU

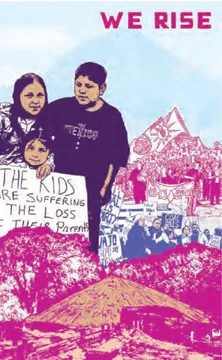

THE FUTURE OF XICANA PRINTMAKING

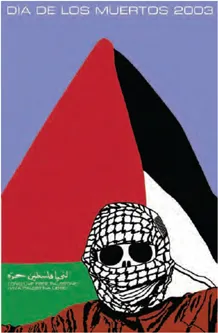

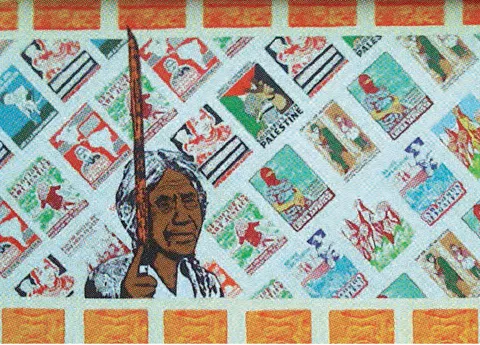

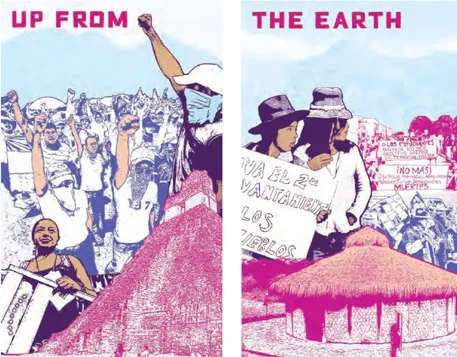

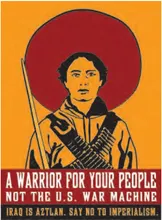

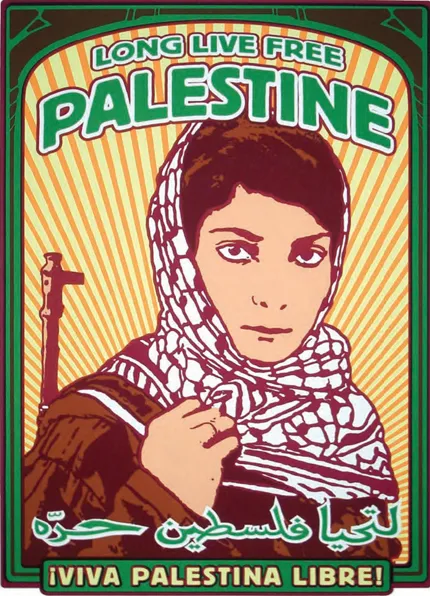

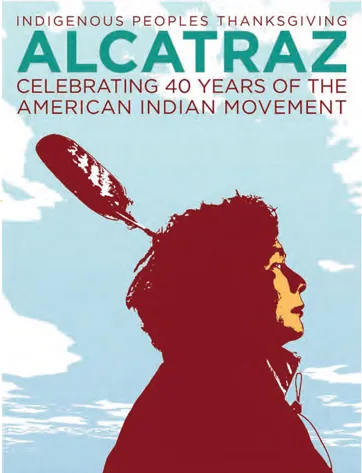

Founded in 2003, the Taller Tupac Amaru is a printmaking collective made up of Favianna Rodriguez, Jesus Barraza, and Melanie Cervantes. Their mission is to create visually powerful screen printed political posters to be used by social movements. In the past eight years they have produced hundreds of posters and graphics used for a wide range of social justice struggles, from Palestinian liberation to anti-gentrification, immigrant rights to Indigenous solidarity. All three members were interviewed by Alec Dunn and Josh MacPhee in the Spring of 2009.

What’s the history of the Taller?

Jesus Barraza: In 1998 Favianna took a class at UC Berkeley with Yreina Cervantes, who asked her to take part in a screen print portfolio at Self Help Graphics in Los Angeles. Favianna’s idea was to digitally create color separations for her print. She asked me to help and the two of us set off on figuring out how the hell we would do that. We took her drawings, digitally reproduced them, and we color separated this nine-color print using Illustrator and QuarkXPress. We did it totally wrong, but we did it. And it was right after that, in the parking lot of Self Help Graphics, that we first talked about having our own studio. About three years later, I got a job at the Mission Cultural Center in San Francisco as a graphic designer. Part of my job was to design the screen-printed posters for their exhibits. That’s how I got involved in screenprinting and then it jumped from there.

While I was at the Cultural Center we pretty much had free reign of Mission Grafica (the printmaking studio housed there), but once I left we had nowhere to go. After that I started working with Favianna at the graphic design business her and Estria Miyashiro were running at the time, called Tumis. There was an idea to start a T-shirt arm of the business, so we set up this T-shirt screen print studio. And that’s where the Taller was born.

Favianna Rodriguez: One of the reasons that we were able to get materials cheap was because all these older printers, our mentors, were no longer screen printing or they were going digital, trying to embrace new technologies. We were already working in these new technologies, so we were really trying to set up a space where we could print by hand. All this equipment was lying around, and we took it and set up our studio.

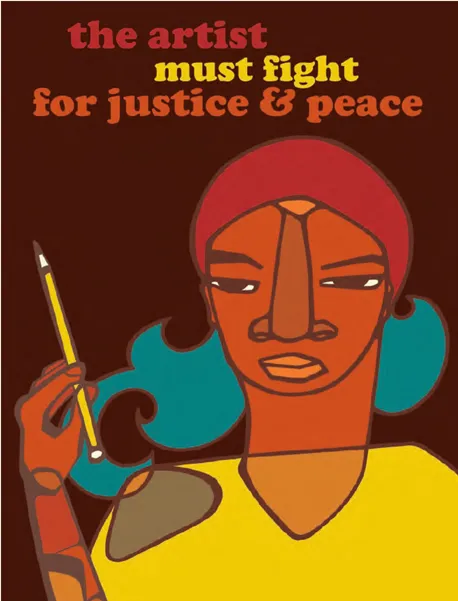

Because we were already running a design firm we were almost immediately making posters for community and political organizations. We can definitely outsource posters to offset printers, but often groups need things faster, cheaper, in small runs, or that aesthetically are more like propaganda posters. Screenprinting became one of the design options that we offered. When you get hired as a designer it’s a really interactive relationship where you have to follow what the client wants, but when it’s a collaboration between an artist and an organization, we have more of a chance to have an artistic voice. And we can get much more radical.

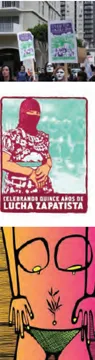

JB: On my end, I had done a few jobs for people or organizations where I designed posters for them and had them offset printed. But I didn’t really have the money to print large runs of my own posters in offset, so screen-printing was about being able to find my own voice: posters that just really came out of a raw idea that I had about the Zapatistas, or Angela Davis, or Palestine, or about something that was going on in the Mission. It was really an opportunity for me to voice my opinion and put myself out there in a way that I had never been able to do before.

How did you originally meet?

FR: We met in college in 1996.

JB: I was at San Francisco State, but living in Berkeley because both of my sisters were at UC Berkeley, living off-campus at Casa Joaquin Murrieta, a Chicano co-op. They moved out, but got me housing there. I started working on La Voz de Berkeley, a newspaper that my sister had started a few years back, which was an oppositional Xican@ paper. That’s how I got involved in UC Berkeley campus politics.

FR: The co-op was a place where a lot of Xincan@ activists lived and worked and there was history there. In 1999, the Third World Liberation Front, which had originally been organized in the 1960s, was reborn, and led student strikes and hunger strikes because the school was trying to cut the Ethnic Studies Department. Jesus and I had already been collaborating and living in the same space, and we were going in the same direction, towards media, technology, and arts. So when the hunger strike happened we coordinated the media and cultural support, like fliers and the newspaper. It was really significant because it meant that we would write, develop art, and do graphic design together. We would teach each other stuff. Jesus taught me how to design. Marco Palma taught me how to write web code. All this skill sharing was happening around media production.

JB: Our first collaborative effort was called Ten 12. It was an artist/techie collective made up of Favianna, myself, Marco, and Jose Lopez. We had the idea of making art and websites and working on tech-based projects. It was the late ‘90s, so the web was really new. That was the first iteration of our collective work, which eventually turned into Tumis and the Taller. It’s been an evolution.

What were you doing at this time, Melanie?

Melanie Cervantes: I was being exploited! (Laughter)

I was working. My trajectory is a little bit different than Favianna or Jesus. I wasn’t tracked to go to university out of high school. I worked for five or six years before I came to the point where I was like, “This is so fucked, I’m really skilled and it doesn’t seem to matter: men get promoted above me, people that don’t have the same skill sets get promoted above me, white folks get promoted above me.” I was working in retail and in the fashion industry, and really was only able to survive because I was doing custom clothing for folks.

I loved color, but being able to express myself was more utilitarian and more of a way to support myself. It wasn’t until I went back to community college and started doing organizing and cultural work for campus organization that I started using art as a creative tool, but I didn’t think I was an artist; I was just making “stuff.” I was doing community work and doing what was right. I didn’t have political ideology and I didn’t have the experience to name what I was doing. As I finished the two years I needed to transfer to a bigger school, I really came to see that I wanted to pursue ethnic studies. When I got there it took me awhile to embrace being an active agent of change and an artist. It was only after the encouragement of a Xicana artist, Celia Herrera Rodriguez, who really pushed that identity. She was like, “You’ve been doing this, you just haven’t named it.”

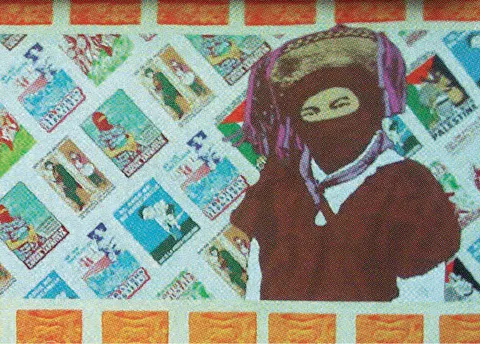

So I really started my art practice doing fabric, textile work, and stencils. The fabric work really came out of Celia pushing her students to do what they knew, and I was like, “Well, I learned sewing from my mom, and my mom learned it from her mom, and her mom learned it from her mom.” It’s a generational thing, and a source of empowerment, this ancestral passing down of doing work that talked about being an Indigenous Xicana. At the same time, I was seeing a lot of stencils online and seeing that a lot of the stencil artists in the Bay who were well known were white men, and I thought, I can do that too as a Xicana. So I started at first by printing out other people’s stencils and figuring out how to cut. I was doing campus organizing around Proposition 54, the racial privacy initiative in California that would ban the collection of racial data, which was a campus issue. I started printing all these stencils to raise awareness. I look back now and see they’re not the greatest stencils, but it was my introduction to making reproducible art.

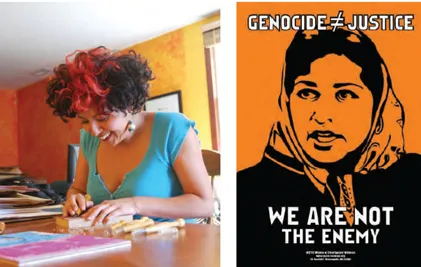

At this point I had actually seen Favianna’s and Jesus’s work but I hadn’t met them. I met them when my employer hired Tumis to design business cards. A year later Jesus and I were dating. I was producing work, big painted banners that had the graphic style of posters. Jesus sent images of my work to Favianna and she was like, “She should be in the Taller.” That was a few years ago.

FR: A lot of us Brown and Black folks are not trained in art school, but end up in college and take ethnic studies classes if we can. Chicano artists are not getting hired at art schools, they’re getting hired to teach seminars at universities, so we get pulled into the arts though this back door. This is one of the only ways we can engage with professional artist of color. The reality is that there are not enough Chicano, Latino, and Black printmakers.

I teach a lot of white kids how to do linoleum block printing because of the places I get invited to teach. But when I teach youth of color, there’s a whole other layer of commitment because, again, these young people are probably not going to go into an art career. One thing we’ve been struggling with is that we don’t get to mentor a lot of youth that look like us. We always try to be good mentors, but sometimes it feels like we’re only one tenth the mentors we had.

MC: Yeah that’s a huge challenge. How many one-off workshops do we do where we give a general introduction, but we can’t ever really get deeper into it? How do we go beyond the one-off workshop? Even if it’s a seven-day workshop or a three week workshop? We’re gonna try and experiment with doing some internships and apprenticeships so we can try and go more into depth. We don’t have a huge infrastructure. We really operate from a few seed grants and mostly out of pocket. The models we’re trying to build and learn from have to be better than the non-profit model, we need to look at groups like OSPAAL (Organization in Solidarity with the Peoples of Africa, Asia, and Latin America) in Cuba and the TGP (Taller de Gráfica Popular) in Mexico.

You mentioned the Third World Liberation Front and the 1969 student strike. Rupert Garcia, Malaquías Montoya, and the origins of the modern Chicano printmaking movement came out of these strikes. Mission Grafica had also been a hotbed of political printing in the 1980s. Were you aware of this history? How do you relate to it?

JB: I was lucky because I had two sisters who went to college and every year after my first year of high school my sisters would bring back their books, so I was reading Karl Marx, but they also brought back the exhibition catalog for “Chicano Art: Resistance and Affirmation (CARA),” this big art show that happened in the late ‘80s. It was an exhibition that had toured big museums, that was where I first learned about Rupert García, Esther Hernández, and Juan Fuentes.

FR: As far as collectives, when we first started organizing we looked up the points of unity of Inkworks, which is a collectively run offset p...