![]()

Bands

• Minor Threat

Interview with Ian MacKaye

• ManLiftingBanner

Interview with Michiel Bakker, Olav van den Berg, and Paul van den Berg

• Refused

Interview with Dennis Lyxzén

The Shape of Punk to Come

• Point of No Return

Bending to Stay Straight

Interview with Frederico Freitas

• New Winds

Interview with Bruno “Break” Teixeira

![]()

Minor Threat

Interview with Ian MacKaye

Ian MacKaye was a founding member of the early 1980s Washington, DC, punk hardcore bands Teen Idles (1979/80) and Minor Threat (1980-83). He was one of the most important influences on the development of the US hardcore punk underground, and—albeit unwillingly—the instigator of the worldwide straight edge movement. The Minor Threat songs “Straight Edge,” “In My Eyes,” and “Out Of Step” remain the most referenced songs in straight edge communities. Ian continued his musical career with the bands Embrace (1985/86), Fugazi (1987 to present), and The Evens (2001 to present). He co-founded Dischord Records in 1980 and still runs the label out of “Dischord House” in Washington, DC.

Discography:

• Minor Threat, 1981, Dischord Records (EP)

• In My Eyes, 1981, Dischord Records (EP)

• Out of Step, 1983, Dischord Records

• Salad Days, 1985, Dischord Records (EP)

• Live, 1988, Dischord Records (DVD)

• Complete Discography, 1989, Dischord Records

• First Demo Tape, 2001, Dischord Records

Since you asked me about this the last time we spoke: I checked on how many white guys in their thirties and forties we have in the book. It’s about twelve out of twenty.

That’s not so bad. I mean, it’s not that you are doing anything wrong. It’s just that there exists a certain kind of people who put a claim on history; and this seems to be a particularly acute pathology amongst aging white dudes. It’s like history should somehow be their province. I find this really disturbing. Mostly because I’m a white guy and I’m forty-six and a lot of people ask me about history, and I just don’t want to be another one of them dudes, ‘cause I don’t claim history. That’s also why I don’t read a lot of punk histories, because, having been there, I started to understand how people who write histories—or about histories—ultimately tend to shape them into manageable narratives, and in doing so they pervert or distort the reality. And since I was there, it’d be difficult for me to read these books without going, “That just did not happen that way!”

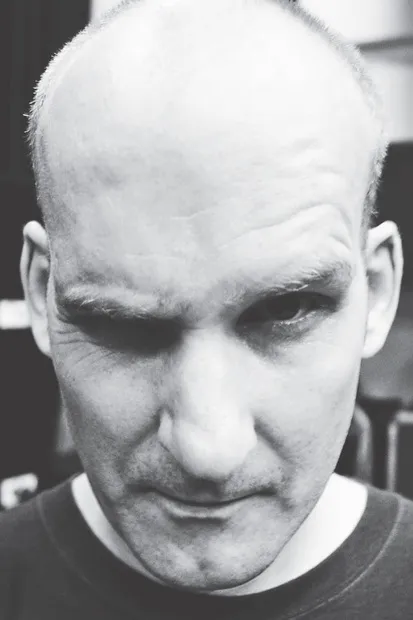

Well, this book doesn’t focus so much on history, I suppose. I think it’s mostly about gathering people’s thoughts on all sorts of issues. I mean, sure, I’ll ask people about history too, and I’ll probably ask you a couple of questions about DC in the 80s, but I mean, you can dodge those if you don’t want to talk about it... (Image 1.1)

Image 1.1: Ian MacKaye, São Paulo, 2007 Daigo Oliva

Oh, I don’t mind talking about it. It’s just that I think of it more in terms of being somebody who’s experienced something and is willing to share these experiences. The problem is that within our culture—and when I say our culture, I specifically mean American culture, but I think it extends to Western culture in general—there is a celebrity factor that makes people who are in the public eye appear to be all-important as opposed to those who just do their work and stay on point. There is the classic moment when people say, “Yes, and then punk, or hardcore, or straight edge, or whatever, died.” But it always died when they left the picture or when their band split up. It seems that they are talking about an energy that was contained within them—whereas I see an energy that is a constant ever-flowing river. And this river has always been there, and it always will be there. And what this river ultimately stands for is the free space in which unconventional, unorthodox, contesting, and radical ideas can be presented.

When I first approached you concerning this project I sent an email saying that I wanted to talk about the “political dimensions of straight edge.” You said that this set off alarm bells for you. Why was that?

I mainly said that because I was born and raised in Washington, DC, and people obviously associate me with the town and its politics. When you wrote that, I felt that you were perhaps trying to appeal to what you might have thought was my political leaning—like you would say, “Look I don’t want to ask you about straight edge, I want to know more about the political stuff because you are from Washington, DC.” And so I was like, whoa, I don’t know what the political dimension would be in that case? I think a lot of people assume that because I live in Washington I’m really caught up in the kind of politicking in a way, because the White House is here, or the Congress.

However, what I really learned from living in a city in which you have an industry like the government was that the way to navigate these institutions is to never engage with them, and to work on the margins instead; to always work around them. There was a saying amongst the young punks here about how if you went to public schools in Washington, DC, you learned two basic things: one, how to wait in line; and two, never ask for permission because the answer is always no. So the thing to do was: just do it, don’t ask for permission! At some point the authorities would come along and say, “You can’t do that!” but then you just said, “Oh, I didn’t know.” If you had asked them, they would have just said no right away. Mainly because of the bureaucracy and the sludge of the administration. They just didn’t want to do any extra work.

This played a really big part in the development of the punk scene: we didn’t ask, we didn’t get permission, we didn’t get licenses, we didn’t get copyrights, we didn’t get trademarks, we didn’t fill out any forms, we didn’t get lawyers ... We just rented rooms and put on shows, and we never formalized anything with the government whatsoever. We just put on these shows that were completely illegal, but nobody cared, because, essentially, you didn’t give them the opportunity to care.

But taking that initiative without asking for permission is a political statement, right?

There is no doubt about that. See, email is a very stupid form of communication and I balked when the word “political” appeared. I don’t know you, I’m not sitting with you, I can’t understand you, I don’t hear the tone of what you are saying. The word “political” is just a difficult word. Many people ask me whether Fugazi is a political band, or Minor Threat ... Well, of course! Every band is political. Everything is political. Every action is political. But I think there are plenty of people who consider themselves political activists and who do not believe that these bands are political because they don’t do this or they don’t do that; like, they don’t go to this particular protest, or they don’t sign this particular petition, or on their liner notes they don’t list this particular organization.

It just depends on what one’s relationship with the word “politics” is. I know that in this country—at least during the last decade, but I would say probably during the last twenty or thirty years—the overarching dominant political party is not the Republican Party or the Democratic Party; it is the “Apathetic Party.” For example, there are many bands that do not want to think about where they play, who they play for, how much they charge, what the arrangements and settings of their shows are, etc. These are people who feel like that’s just not part of their world. This is an example of the politics of apathy.

When you say that everything is political, is that because everything we do affects others?

I guess I would say yes. I mean obviously everything we do—or don’t do—has its effects. There are many ways to illustrate this. For example, for the life of me I cannot understand how bands would submit to playing shows that are limited to people over the age of twenty-one. I find it unconscionable. Today there are a significant number of people playing shows whose love of music goes back to seeing bands like Fugazi when they were fifteen or sixteen years old. However, now that they’re in a band themselves this is somehow no longer relevant. And this is a political action on their part, because what they are saying is: we support the status quo, we support the corporations, and we do it because it’s easier for us, because it’s more convenient for us, and because it’s more lucrative for us. So by not doing anything about this, they are making a very political statement—especially in this day and age when politics are governed by business.

Let me ask you about the famous “political” DC hardcore scene in the 80s. I think we’ve already clarified what you understand as political, so I’m not going to ask whether it was “really” political or not. But let me ask you this: was the involvement in what we might want to call “social struggles”—like anti-racism, gender and sexuality issues, support for the homeless, etc.—really a crucial part of the scene? I’m asking because you always hear conflicting reports. There are some who claim that this was important to the kids in the scene, while others say that it was all just about music and individual rebellion...

Who are all these people?

People who write books about the history of hardcore, for example...

Oh, okay. Well, punk, or underground music, or hardcore, or whatever you want to call it, is not singular. I mean, it is essentially a projection of every person. So, for instance, for people who filter things politically it was one thing, while for people who filter things purely through amusement it was another.

In my estimation, the early punk scene, in the late 70s and early 80s, was going through a birthing process, and every time something new is created you have friction. I think that in the early days much energy was being spent on recognizing that we were part of something new, and a lot of us were trying to get our minds around what the hell it was.

Punk rock in the beginning was so many different people who came from so many different places. They were all these outcasts, all these people who just did not fit in for various different reasons. Some people didn’t fit in because they had troubles with their families; some people didn’t fit in because of their sexuality; some didn’t feel normal psychologically; some didn’t feel normal politically. And all these sorts of margin walkers, these people who were outside, joined together and gathered under this new manifestation of the underground. And there was a lot to learn, a lot to take in, and there was also a sense of circling the wagons...

Like defense?

Yes, exactly. You create a position of defense. I think that’s where a lot of the really tough guy posturing, the spiky hair, and the leather jackets came from. It was basically circling the wagons.

The activism came in where, coming out of the late 60s as a child, you felt that the government should never be trusted and that authority should always be questioned. In this sense, I was always interested in activism. The problem was that you had people, certain political activists, who only saw music as a way of raising money for their causes. They only had interest in bands when they played for their fundraisers. I reject that. There are probably some people in music who don’t take politics seriously, but there are certainly many people in politics who don’t take music seriously. But the thing about music and politics is that music was here before politics. Music was here before language. This is no fucking joke!

I know that the big industries have trivialized music in many ways by turning it into entertainment or amusement, but music as a point of gathering is something that goes back all the way to the beginning. So what I was often dealing with when talking to political people was an attitude like, “Well, we don’t really care about your music, as long as you can generate an audience and we can get some money...” I remember with Fugazi, these people would come to us and would want us to play for them, and we’d say, “Okay, we do a $5 door,” and they’d say, “Oh no, we should do a $25 door,” and we’d say, “No, we do a $5 door.” They were unable to appreciate our insistence of having a low door price, but this is activism, this is activism in our own life.

So, yes, even in the very beginning of the underground punk scene, in 1979, 1980, there were people who were just political activists, who really didn’t give a goddamn about the Teen Idles or about Minor Threat. They were just concerned with their own issues. And some of them were a little obsessive. They were kind of—they were almost like a cult. So I think that, in response to that, we—and I mean Minor Threat, SOA, that era of early hardcore bands—moved away from “Politics with a capital P,” like, the formal version of politics. We said, “We’re not interested in your politics, what we are interested in are personal politics; we’re interested in this music, in this community, in this scene.”

At the same time, we did do benefits, but we always demanded that the benefits were actually connected to the shows themselves. Like, we would have a show—and then give away the money we made. For example, we did a number of benefits for the Bad Brains ‘cause they were always getting their stuff stolen. We also did benefits for venues that were getting evicted, or for kids who were getting evicted from their house.

HR from the Bad Brains also had the idea to do a “Rock Against Racism.” There had been these Rock Against Racism shows in England, where the Clash and Sham 69 and those bands played. But HR just saw those events as rock concerts for a lot of white kids. So he said, “Well, we’re gonna do a Rock Against Racism here in DC, but we’re gonna go play in a black neighborhood.” Washington, DC, especially then, was primarily a black town. The majority of the town was black, like 60-70 percent, and there were neighborhoods that were 100 percent black. It was very polarized. So HR organized a couple of Rock Against Racism shows, including one with the Teen Idles, Untouchables, and the Bad Brains. We just played in a housing project. In my mind that certainly counts as political.

So this was all in the early 80s?

Yes. And then by around 1984 things changed. The elders in the DC punk scene began to drift away for various reasons, and the scene was left to these younger kids. There was a lot of senseless violence going on and it was really off-putting. The problem was not limited to DC. Skinheads seemed to be rampant all over the United States. In other towns, there were kids who were trying to battle with skinheads. They wanted to beat them up and chase them out of town. I thought that was just ridiculous. In DC, we decided to just create a new scene instead. That was certainly a political action, too. Not least because a part of creating a new scene created a situation in which we, being in our early twenties, began thinking about the larger world. I believe there was a very natural evolution, which then led to what became known as “Revolution Summer.”

Can you tell us a little more about that? What happened?

I would say that Revolution Summer was an infusion, a moment when the DC punk scene and its personal politics suddenly merged and dovetailed with formal politics. We got involved in political action. Reagan was in office and the apartheid issue was really big. We were discussing gender issues, environmental issues, diet issues, and so on. It was a time of politicization.

Unfortunately, the name Revolution Summer has caused some false interpretations—which is partly our fault because we came up with it. Some people were like, “Oh, look, they think they are being revolutionary!” But that was not actually what we were thinking. We used the word “revolution,” and it is a very strong word, but it was not to suggest that we were creating a revolution. For us Revolution Summer was all about our immediate community. It really came out of a loss of direction or emphasis.

How so?

In 1983, a lot of people were very discouraged. A number of bands, most notably Minor Threat, Faith, and Insurrection, had broken up, and even though there were other bands—good bands: Government Issue, Marginal Man, bands like that—the bands that had been crucial for us, the kids I hung out with, were gone. Especially Faith, who were just an enormously important band—I think a lot of people don’t realize how significant they were. Anyway, 1984 kind of turned into a dark year, and no bands were really forming. Eventually, everyone was like, “Well, we’re gonna do something!”

So we decided to pull something together. First we planned “Good Food October.” The idea was that in October 1984 we were all going to eat good food, we were going to make good music, and we were going to be politically active. But then October came and went. So we set a new target date for the summer, and this time it worked.

What kinds of actions did you do?

One of the most successful was the Punk Percussion Protest, something that I remember being hatched at Dischord House. We initially discussed the idea of putting a band on a truck and driving back and forth in front of the South African embassy to protest apartheid. We gave up on that c...