![]()

1:

Revolt into Style: New Sounds in New York and London

Like Pete Townshend of The Who, Keith Richards of The Rolling Stones, and Ray Davies of The Kinks, Paul Simonon and Mick Jones transposed their art school aspirations into musical aspirations. Art schools on both sides of the Atlantic offered their students loosely structured days informed by lessons in theory, craft, and creativity. The exigency of creativity inspired students with musical talent to pursue muses in the visual and sonic arts and, in turn, to paint by day and play house parties at night. These schools, then, served as incubators for the protagonists of the British Invasion of the 1960s and the emergence of punk (and new wave) in the 1970s. The punk circles of downtown Manhattan also included organic punk intellectuals, whose interlocutors included Andy Warhol, French poets, and Mad magazine’s Alfred E. Neuman.

TODAY YOUR LOVES, TOMORROW THE WORLD

Simonon was born in 1955, and grew up in Brixton, in inner-south London. When he was eight years old, his mother and father separated and, seven years later, Simonon moved in with his father. A mishmash of pages from art history books adorned the walls of their apartment, and Antony Simonon encouraged his son to sketch masterworks by Johannes Vermeer and Vincent Van Gogh. Between the sketching and, at the behest of his father, leafleting for the Communist Party, Simonon found the time instructive. “Being with my father made me self-sufficient,” he recalled. “It was tough but I needed it. I learned the value of hard work.” Simonon’s work ethic served him well during basic training on the bass, led initially by Jones and, in 1978, by producer Sandy Pearlman.1

Simonon’s diligence reaped rewards, to begin, in the form of a scholarship to the Byam Shaw Art School. From 1974 to 1976, he later remembered, “The other students thought my pictures were great but the teachers used to take the piss out of me.” Simonon’s strength was figurative art, but the lessons of his instructors, who fancied American abstract art, eventually found expression in his low couture and stage backdrops for The Clash. If there was no future for Simonon at Byam Shaw, he did have the good fortune of good looks and good timing.2

Jones, like Simonon, was twenty years old in 1975, a fellow Brixtonite, and an art student. Unlike Simonon, Jones had homely hair, an imperial overbite, and could actually play guitar. Jones lived with his grandmother on the eighteenth floor of Wilmcote House, an exemplar of Le Corbusier’s machines-for-modern-living, which provided the backdrop for Clash treatises on chronic boredom (“London’s Burning”) and youth-on-youth violence (“Last Gang in Town”). In his teens, Jones staved off boredom by following the Queen’s Park Rangers Football Club and tuning into deejay John Peel on Radio London, a pirate station afloat the MV Galaxy, off the coast of Essex. Jones read the music weeklies, bought the latest LPs, and attended Hyde Park concerts by Traffic and The Rolling Stones. (Jones also pored over copies of Creem and Rock Scene sent from Minneapolis by his mother.) At sixteen, Jones was a self-starter on stylophone (a stylus-operated keyboard) and, in fairly quick succession, drums, bass, and guitar. With fellow Mott the Hoople devotees, Jones played in Schoolgirl, and eagerly solicited technical tips from the older kids. In their eyes, his hunger appeared “embarrassingly naive,” Jones recalled. “I was always asking how they did it. I think they couldn’t understand where this kid was coming from. ‘Why can’t he just be a lot cooler?’”3

After a stint in 1974 with The Delinquents, a glam-rock outfit, Jones teamed up with bassist Tony James to place a classified ad in a July 1975 issue of Melody Maker, a rock’n’roll weekly: “Lead guitarist and drums to join bass-player and guitarist/singer, influenced by Stones, NY Dolls, Mott, etc. Must have great rock’n’roll image.” That October, though, Jones hedged his bets on a future with James, and attended an audition on Denmark Street, London’s version of Tin Pan Alley. The fledgling band was impressed with Jones’s guitar skills, but their follow-up efforts ended in vain. When Glen Matlock and Malcolm McLaren arrived at Jones’s address, his housemate grew suspicious, turned them out, and never reported the inquiry of the founding members of The Sex Pistols.4

In January 1976, Jones and James hired Bernie Rhodes as their manager, continued to audition drummers and, in archetypal punk effrontery, settled upon London SS as their appellation. By all accounts, Rhodes’s back-story before the late 1960s is difficult to discern. His mother, pregnant with Bernie, arrived in London at the close of World War II. She worked as a seamstress in the 1950s, and Rhodes spent the early 1960s allegedly sharing ideas about rock, art, and fame with Marc Bolan, of T. Rex, Townshend, and Mick Jagger. Rhodes mash-mixed these ideas with agit-prop slogans from the Situationist International, including “Be reasonable, demand the impossible” and “The arts of the future can be nothing less than disruptions of situations.” In 1974, Rhodes began working at Sex, the shock-and-awe clothing boutique owned by McLaren and Vivienne Westwood. A fall collaboration between McLaren and Rhodes gave rise to their first manifesto T-shirt, with its challenge to each passerby noted in large, bold script just below the collar: “You’re going to wake up one morning and know what side of the bed you’ve been lying on!” In smaller typeface below, the shirt compiled the “hates” (“YES [the band] … synthetic food … David Hockney and Victorianism”) and the “loves” (“Archie Shepp Muhammad Ali Bob Marley Jimi Hendrix … Kutie Jones and HIS SEX PISTOLS … Guy Stevens records”).5

In this text lay the germ cell of the London punk scene. Rhodes’s study of Marxist political theory left him well-versed in the importance of cultural revolutionaries, and the shirt reflected his fascination with avant-garde musical figures from the black Atlantic. Steve “Kutie” Jones, petty thief and eventual guitarist for the Pistols, had been hanging around McLaren’s shop for years, hounding the aspiring impresario to support his musical aspirations. Guy Stevens possessed an encyclopedic understanding of black music, worked for Island Records, and produced a handful of albums for Mott the Hoople—a band that loomed large in the imaginations of Strummer and Mick Jones.

Within the logic of loves and hates, a number of paths could have been forged. The two that would come to dominate UK punk in the late 1970s dovetail nicely with the political maxim often attributed to Antonio Gramsci, the cofounder of the Italian Communist Party: “The socialist conception of the revolutionary process has two characteristic marks which Romain Rolland has encapsulated in his watchword: pessimism of the intelligence, optimism of the will.” (Rolland was a French dramatist, recipient of the Nobel Prize for Literature, and pen pal of Sigmund Freud.) The intellect compiles facts and renders judgment. The will drives the subject onward, regardless of the odds. From his damp prison cell, on the Mediterranean island of Ustica, Gramsci had every reason to despair. Still, he wrote on, hopeful that his words might inspire his comrades and their progeny. In the UK conception of punk, McLaren and the Pistols would select the path of pessimism, dwell long in the negative (“God Save the Queen,” “Pretty Vacant”), and dismiss the counterbalance of possibility. The Clash would take the alternate route, embrace the contradictions endemic to politics, art, and commerce, and ensure Stevens one more collaboration worthy of commercial and critical celebration.6

Rhodes’s first steps along that path entailed the managerial and propaganda duties for London SS. For his audition, drummer Roland Hot arrived with Simonon in tow. After Hot’s turn, Simonon recalled, “Mick said to me, ‘Are you a singer? … Do you want to have a go?’ and I said, ‘Yeah, why not?’” Simonon’s performance of “Roadrunner,” by The Modern Lovers, inspired Jones and James to continue to look for bandmates, until Jones met Simonon again in south London. Jones reported the encounter to Rhodes, who recalled Simonon’s angled countenance and cool demeanor—which, in 2014, still recalled Marlon Brando’s dreamy sidekicks in The Wild One. “Forget Tony James,” Rhodes said, “start a band with that bloke.”7

That April, Jones and Simonon spent hours together in Jones’s flat in west London. They borrowed a bass from James who, seven months later, with William Broad (a.k.a. Billy Idol), formed Generation X. Simonon painted the notes on the fret board, and Jones took painstaking efforts to help Simonon learn the rudiments of rhythm. “I remember Mick introducing me to all his mates,” Simonon said. “‘This is my new bass guitarist, Paul. He can’t play but he’s a painter.’” New bandmates included Chrissie Hynde, who in 1978 would form The Pretenders; and Keith Levene, a self-taught guitarist who idolized Steve Howe of Yes and, in 1978 with John Lydon, would cofound Public Image Ltd.8

On April 23, Jones, Simonon, and Levene attended a gig at the Nashville Room. The headliners were pub-rock favorites The 101’ers, with Joe Strummer on vocals and, as his moniker suggests, rhythm guitar exclusively. Then in their third year on the pub-rock circuit, The 101’ers had just completed the recording of their first single, “Keys to Your Heart,” and had rough cuts of a handful of other originals ready for post-production. According to Nick Kent, of New Music Express (NME), Strummer was “the snaggle-toothed troubadour of the capital’s new bohemian squatocracy,” and the 101’ers’ sound shared more with The Hollies—of “Long Cool Woman in a Black Dress” fame—than the night’s opening act, The Sex Pistols.9

Despite six months of rehearsing and gigging in England and France, the Pistols onstage remained a shabby lot. Their musical shortcomings, though, were eclipsed by Rotten’s I-don’t-give-a-toss nihilism, and their bad-lad behavior. As an opening act on February 12 for Eddie and the Hot Rods, they made their mark by trashing Eddie’s gear, and codified the transgression in Situationist terms: “We’re not into music,” Steve Jones blurted. “We’re into chaos.” On April 23, at the front of the stage, Westwood ached with boredom and, for inspiration’s sake, slapped an unsuspecting concertgoer. The victim’s boyfriend sprang to the offense, grabbed Westwood, and started smacking her. McLaren joined the fray, as did Rotten. The chaos the Pistols had fabricated for interviews spilled onto the stage and, subsequently, was splashed across the headlines of NME and Melody Maker. Lydon’s “I’m-sick-of-being-boring!” aesthetic resonated with writers at NME, who were critical of “lumbering progressive rock acts” and advocated for a renewed alliance between rock’n’roll, rebellion, and fun.10

Another audience member was able to look beyond the melee, and liked what he saw. “After I saw The Sex Pistols,” Strummer noted, “I realized we were yesterday’s papers.” Luckily for Strummer, Jones and Simonon and Levene were ready to court a new front man to make their own headlines.11

URBAN MUSIC GOURMANDIZERS

At the terminus point of Bleecker Street, beneath the most famous awning in Western history, the Bowery contingent gathered to give shape to their own variety of rock’n’roll, joy, and outrageousness. Hilly Kristal opened CBGB OMFUG in December 1973, banking on a country music renaissance and, to keep his options open, devised an acronymic moniker with catholic principles: Country, Bluegrass, Blues and Other Music for Urban Gourmandizers. Previously known as Hilly’s on the Bowery, the club occupied the bottom floor of a flophouse, and its clientele lined the street at eight a.m., eager to be indoors for the next round of drinks.

In spring 1976, on the same weekend that Jones and company identified their muse, New York’s protagonists of the new rock’n’roll filled CBGB to celebrate their appearance in The Blank Generation, the scene’s first representation on celluloid. From April 22 to 24, the film was the opening act for The Heartbreakers, in Richard Hell’s last appearance as a sideman. Over the previous two years, Ivan Kral, of the Patti Smith Group, had recorded 16mm footage of Talking Heads (as a trio), Blondie, The Ramones, Television, The Heartbreakers, The Patti Smith Group, The Shirts, Harry Toledo, The Marbles, The Miamis, Wayne County, and The Tuff Darts, onstage at Max’s Kansas City, the Bottom Line, and CBGB, for posterity, not publicity. “I picked up this Bolex camera at a midtown pawnshop, and started filming,” Kral told me. “I filmed the subway, I filmed the ocean. I filmed people on 5th Avenue. And once I knew everyone around Max’s and CB’s, I took my camera in there with me.” The film, he figured, would be the equivalent of a do-it-yourself video diary: “Like a slideshow for my parents!” he said, laughing. While filming Talking Heads onstage, Kral recalled, “I had my light in one hand, and the camera in the other, and I couldn’t see through the viewfinder, so I was filming David Byrne’s molars, and Tina [Weymouth] was shy, so she often backed away.” To get a well-lit shot of drummer Chris Frantz, for example, Kral had little choice but to wriggle his way from stage left to the vicinity of the bass drum. “It was the first time we’d ever been filmed,” Frantz recalled. “It was really fun, and Ivan was somebody we really liked.”

In a single day, Kral edited the nearly sixty-minute film and, for the audio track, synched bands’ home and demo recordings to the video footage. The black-and-white film is an endearing collage of live footage, candid offstage shots, and audio with varying levels of synchronization. Close-ups of lead singers dominate, and the camera is kind to Debbie Harry’s radiant cheeks, Wayne County’s lovely legs, and Richard Hell’s blankly perfect pout. “We were all there because everyone was excited to see themselves on ‘the big screen’ [laughs]. It was a fun event. We thought of it … like one of Andy Warhol’s underground films,” Frantz recalled. “We knew it wasn’t going to be a Hollywood movie or anything, or have any appeal to mainstream rock audiences, but we thought it was a pretty cool record of what was going on at CBGB and Max’s.”

In the six-season span that bookends the premiere of The Blank Generation, the New York punk scene produced an impressive record of vinyl, too. Patti Smith’s Horses appeared on the shelves of Bleecker Bob’s (and elsewhere) in November 1975. The following spring, critic Lester Bangs had The Ramones (April 23) in heavy rotation and, by summer’s end, blessed Blondie’s “X Offender,” their debut single, with buoying rapture: “[It] contains the best roller rink organ since the Sir Douglas Quintet [and] the best surf guitar since [The Velvet’s] ‘I’m Set Free.’” That autumn, Smith and comrades added Radio Ethiopia to the mix, and Blondie’s debut album led all releases in 1977. In February, Television’s legendary Marquee Moon represented the fifth full-length release from the Bowery camp ahead of the first British punk LP, The Damned’s Damned Damned Damned.12

PUNK THEORY: AN INTERLUDE

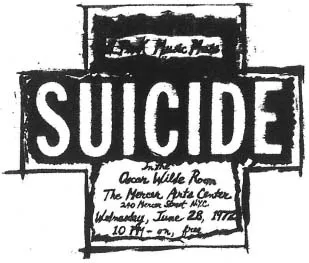

At the time, “punk” as a catch-all had yet to take hold. The experimental duo Suicide promised “punk music” in a 1970 flyer, and added an eschatological twist by hosting a “punk music mass” in 1972, at the Mercer Arts Center. Three years later, while Voice scribes increased the use of punk and “punkdom,” the respective organizers of the Christmas Festival at CBGB in 1975, and the Easter Rock Festival at Max’s in April 1976, passed on “punk” to describe the new rock underground. (Our Jewish, club-owning protagonists loved their Christian holidays, and admired one another, too. An early April concert listing for CBGB noted, “C.B.G.B. Salutes Max’s Kansas City Great Easter Rock Festival.”13) Once it gained greater currency, the designation “punk” glossed over the differences in the poppunk, garage-punk, and art-punk musical camps pitched around the Bowery. The differences are considerable, but the musical and performative codes shared by these bands were significant, especially in terms of their adversaries.

“Punk Music Mass” by Suicide, with Reverends Martin Rev and Alan Vega presiding, 1972.

Around CBGB and Max’s, the protagonists of the new sound drew inspiration, in various combinations, from a host of forebears and New York institutions. The Velvet Underground, to begin, offered a compelling, alternative vision of the holy trinity of sex, drugs, and rock’n’roll. On their debut album (Velvet Underground and Nico, 1967), they countered the hippies’ insipid, consonant visions of ...