![]()

PIONEER BUILDING 1

THERE WAS nothing that could be called architecture, and little that might be considered legitimate building, in Fayette County at the time the white man arrived. A previous race had constructed earthworks and stone pyramids, described, respectively, by the scientist Constantine Rafinesque (Western Review, 1820) and the historian John Filson.1 Catacombs containing embalmed bodies were reported in Thomas Ashe’s Travels of 1806.2 But these remains made no contribution to the construction program that was to follow.

Pioneer building grew out of very humble beginnings. The first scouts erected flimsy shelters intended only for a night’s occupancy. These consisted of a roof and one or two windbreak walls made of any available materials, such as sticks and leaves. Determined settlers followed close upon the heels of roving scouts, and the first structures built with any degree of permanency were log cabins, which began to appear around the middle of the eighteenth century. The American log cabin has an interesting history. Today it is fairly well known that the earliest English colonists of Virginia and Massachusetts did not live in log houses, because there was no antecedent for them in the British Isles.3 In Europe the log house is native to Scandinavia, Russia, Switzerland, and parts of Germany, and it was introduced into the New World by the Swedes, who settled along the Delaware River in 1638.4 About 1710 it began to be used independently by the Germans. The Scotch-Irish were the first English-speaking people to employ it, but not until after 1718. By the time of the American Revolution the log house had become the ubiquitous frontier dwelling, adopted by all nationalities, including the American Indian.

The log house presented many features desirable to the pioneer. It was readily constructed from indigenous materials, trees that had to be removed in clearing the land for cultivation, loose surface rock and mud for closing up the chinks between the timbers. The log structure provided a comfortable place of habitation. With its big fireplace and the natural insulation of the thick, all-wood envelope, the log house could be made warm in winter; and it was cool in summer. Construction was not complicated, requiring no extra framework to sustain the walls, and the simplest kind of triangular truss for the roof. In their eagerness to erect a house as quickly as possible, the first settlers made use of newly felled tree trunks, stripping off the branches and notching the ends of uniformly measured logs, which were laid horizontally on a rectangular plan, overlapping alternately at the corners. The fireplace was fashioned of stone, the chimney of small logs, lined with a coating of mud which was hardened to the consistency of pottery by the fire’s heat. The floor was tamped earth, the roof covered with shakes or split shingles. Door and window openings were protected by batten shutters that swung on leather or wood hinges. Such houses were erected singly or clustered together to make a community, the latter often surrounded by a palisade of contiguous upright logs for protection against beast and savage. Because of the perishability of the unseasoned wood that went into these primitive log houses, no examples of the type have survived in Fayette County. A facsimile may be seen in the reconstructed (1926) Fort Harrod at Harrodsburg in Mercer County, some thirty miles to the southwest of Fayette.

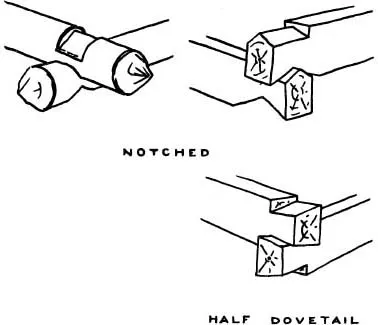

Certain advances distinguish the second phase of log construction from the first. The timbers were allowed to season properly, and they were squared for a more finished-looking and workmanlike job. Two systems of fitting the logs together at the corners were employed in central Kentucky. One was adapted from the notching used earlier, in which the log end was cut away to form a rooflike peak running length-wise on top, with a saddle joint on a cross axis carved into the underside (Fig. 1). The alternative may be described as a modified half dovetail, the indentations made on a slope in such a way that the weight of the logs locked them in place. Old log houses in the highlands of south Germany, using this exact method, indicate a likely origin. The extremities of the timbers in both types were self-draining of rainwater. The notch system was employed in the Patterson, Cleveland, and Watts cabins and the saddlebag cabin, to be discussed below, as well as in a cabin at Winton on the Newtown Pike and the north end of the ruins of the Harp house on the Harp and Innes Road. Examples using the half dovetail are the Bowman cabin on the Woolfolk place at South Elkhorn, and the smaller cabin (presumably used as a storeroom) near the saddlebag cabin on the Armstrong Mill Road. The majority of log houses are weatherboarded over so that their joinery cannot be determined. Among the exposed buildings the predominance of the notch and saddle indicates this to have been the favorite device for locking logs in Fayette County.

1. Systems of Log Construction.

Surviving log houses are to be found mostly around the perimeter of the county, where they have remained untouched by building operations in or near Lexington; but this is no indication of the original distribution. Log houses generally were built close to the more important streams, where the first land claims were staked. They may be divided geographically into five groups: (1) those along the lower end of the Richmond Pike and Jacks Creek Road, near the Kentucky River and Boone Creek, in the southeast corner of Fayette; (2) those built overlooking the various tributaries of North Elkhorn, which extends down through the northeast section of the county to below the Winchester Pike; (3) those on South Elkhorn, that cuts into the southwest corner of Fayette; (4) those on East Hickman Creek, flowing southwardly midway between Lexington and the Kentucky River; and (5) the group on the principal branches of the Elkhorn, including Town Fork that traverses Lexington. The first house to be discussed was located here. Composed of a single room, it represents the minimum in frontier housing.

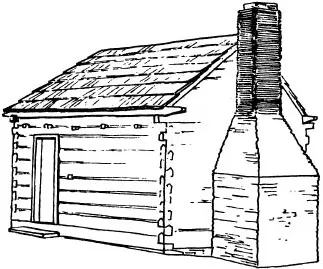

PATTERSON CABIN Built probably before 1780 in what was to become downtown Lexington, the log cabin of Colonel Robert Patterson—one of the founders of the community in 1775—was moved to the Patterson property between High and Maxwell, Lower (now called Patterson) and Merino streets about 1783. Later Patterson went to live in Dayton, Ohio, where he died in 1827. Purchased by his descendants, the cabin was taken to Dayton in 1902 and set up in a public park. It was returned to Lexington in 1939 under sponsorship of the State Highway Department and given a site on the campus of Transylvania College, of which institution Robert Patterson had been a trustee. The house is nearly square (Fig. 2). It has a door in the front and a small window in the back wall. Another window, lighting the garret, is in the gable opposite the chimney. As reconstructed, the cabin has a plank floor raised off the ground, a stone foundation, and a large stone chimney, the sides of which slope inward above the fireplace, supporting the flue of small notched logs. The ends of the ceiling joists project slightly and those of the two plates farther beyond the wall planes, which is a feature normal to log construction. The roofing is of split wood shingles.

2. Patterson Cabin as Set Up on the Transylvania Campus.

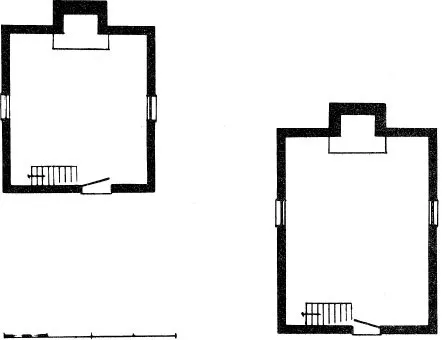

3. Plan of Cleveland Cabins.

The remaining single-room cabins in Fayette County are not numerous. One is to be found on the Moore place near Bethel. The original section of the northern Harp house (previously mentioned), on the Harp and Innes Road, is another, enlarged into a two-story frame and brick residence. Two stone chimneys on the Watts place above Athens mark the sites of two others, with an existing log stable nearby. The cabin without a chimney on the Berry farm (Armstrong Mill Road) has been noted. A similar structure, also probably used for storage, is at the Carter place on the Military Pike. The two Cleveland cabins, in the first geographic division, are the best preserved in the county.

CLEVELAND CABINS Eli Cleveland obtained 740 acres of land between Boone Creek and the Richmond Pike in 1786, and probably built shortly thereafter the two cabins standing east of the later main house. Approximately half again larger than the Patterson cabin, these buildings measure 18 by 19 and 18 1/2 by 23 1/2 feet in area, and are placed 14 feet apart, oriented alike, but not set on an axis, undoubtedly for privacy and a wider vista from the windows (Fig. 3). Each has a shouldered chimney entirely of stone, a door opposite in the gable end, and a single window, now provided with glazed sashes, in each sidewall (Fig. 4). A steep, ladderlike stairway to the side of each door gives access to the loft, where sleeping quarters were provided for the younger boys. The building of a second cabin similar to the first constitutes the simplest mode of pioneer expansion; in this case it is possible that the smaller structure housed the slaves. A large log barn with flanking lean-tos also is on the Cleveland farm, and another like it is to be found at Locust Grove, five miles west of Lexington north of the Leestown Pike.

4. South Side of Cleveland Cabins.

The one-story house divided into more than a single room was the next advance in building. The cabin on the south side of the Iron Works Road, halfway between the Newtown and Cynthiana (Russell Cave) pikes, contains two rooms, with an enclosed staircase to the garret adjoining the dividing wall. Shallow gun closets flank the chimneypiece in the west room. The Fry cabin on the Paris Pike at Hughes Lane and the servants’ cabin back of the Hunter house at the county line on the Tates Creek Pike have two rooms and two terminal chimneys.

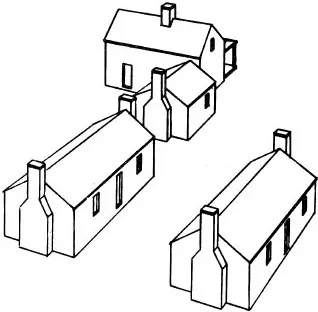

5. Bird Hill. Conjectural Restoration.

The ruins of a log house with a central chimney and the foundations of a pair of long cabins with end chimneys mark the site of a group once known as Bird Hill, which stood a mile directly west of the Cleveland farm on a prominence overlooking the deep valleys bordering the Kentucky River. Here is virtually a miniature settlement (Fig. 5). An arrangement resembling Bird Hill apparently existed in the early log buildings at Winton on the Newtown Pike, and it was translated into more substantial materials with the construction of the main pavilion of brick in 1823, the log units continuing to serve as subsidiary buildings until after the Civil War.5

WATTS HOUSE A distin...